What’s the best place to go looking for happiness? In this case, an English club and the countryside. An Aston Martin and a Rolls-Royce don’t hurt either. They were “quite nice”, as the Brits like to say.

Of all the cars we’ve had the pleasure of test-driving over the years for the illustrious ramp magazine – which basically means driving around and having fun – the ones that stuck with me most were the Rolls-Royces. I’ve always had a soft spot for these anachronistic, time-warped giants with their starlit headliners and massive seats, their uncanny soundproofing. They feel like a message from a bygone era, when people didn’t rush from one appointment to the next every day and the auto industry wasn’t obsessed with efficiency, frugality and sustainability.

I’ve always looked forward to any encounter with a Rolls. Sure, the chances of spotting one in Berlin are slim, but it depends how you do the math. Personally, I go by the logic of that old blonde joke: “The chances of a blonde running into a dinosaur are always fifty-fifty. Either she runs into one or she doesn’t.”

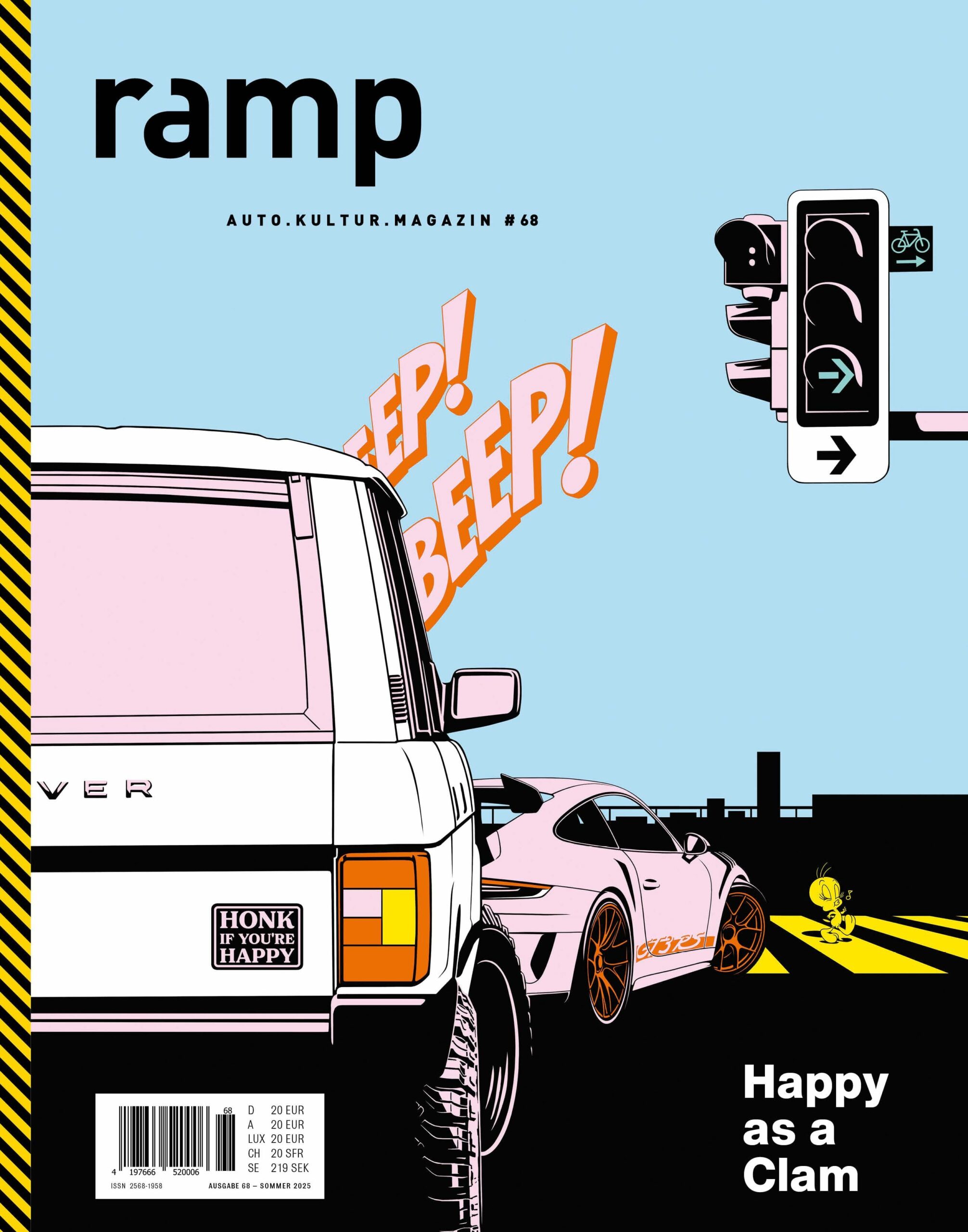

Until now, I’d only seen Rolls-Royces in James Bond movies – or driven them myself, when ramp managed to get one and handed me the keys. The theme of this issue is “Happy as a Clam”, a phrase that originated in the northeastern United States but is also popular with Brits when they talk about being especially content. So British happiness, then – and that of course called for a Rolls. With two cars, an Aston Martin and a Rolls-Royce, we drove through Charlottenburg to an English club on Thüringer Allee, officially called the International Club Berlin and under the patronage of King Charles III. Even though I’ve lived in Berlin for over thirty years, I’d never heard of this club. It must be one of those secret sanctuaries where city dwellers go to escape the daily grind, a place where visitors lounge by the pool or hop around in tennis shorts.

The club used to be an Allied officers’ casino, known for its wild parties. British officers were even said to have shown up to dinner on horseback. These days the place has a refined, upper-middle-class vibe – with a good restaurant, a park, a pool and sports facilities. King Charles, the club’s patron, looked down at us from his portrait with serene indifference as we pulled up in front with our cars. The members, on the other hand, seemed quite taken by the elegant vehicles.

Michael, ramp’s editor-in-chief, has a good instinct when it comes to choosing themes for new issues – sometimes a bit cryptic, always poetic. “Us, out on the road, in life, in the moment. All around, treasures gathered from the shoreline of life. Time to dive into the clam! Windows down, music on,” he wrote to me beforehand.

It was a glorious drive. The bass from the Aston Martin’s speakers was so powerful you couldn’t really call it a sound system – it was more like an air massage, gently massaging my ears from the inside and out. Maybe that was also thanks to my playlist: British hip-hop. With a light heart, I handed the sporty Aston Martin over to the boss – he’s always been a sucker for fast cars – and switched to the Rolls.

The club hosts had invited us in for tea. “Man, we really lucked out with the weather,” said our photographer.

German happiness often means finding the silver lining. “You got off easy,” the German doctor says to a patient with a broken leg – after all, it could have been worse. A fatalistic German saying goes: “It could always be worse.” In other words, disaster was narrowly averted. Lucky pig. In Germany, luck is a pig.

In Russia, happiness is as fickle as a cat – it can turn in an instant or bring misfortune to others. A Russian proverb says: “One man’s joy is another man’s death.” Back home, one person’s happiness always came at someone else’s expense. And the Brits? They have countless ways of talking about happiness, depending on mood and moment. The fine distinctions are really only clear to natives. Who can tell the difference between luck, happiness, felicity, chance, bliss and beatitude? But some kind of cozy sentiment is always involved.

British happiness, most likely, is a clam. I have no idea what it feels like to be a clam, or whether clams are even capable of emotion. People are constantly projecting feelings onto other living beings that probably don’t have them. How do we know what a clam feels like in its shell? Or whether it even knows where it is? All I know is I felt safe and sound inside the Rolls-Royce. The plan was to leave Berlin after tea and continue our search for British happiness out in Brandenburg, where my wife and I have a second home. Since the pandemic, we’ve been spending more time in the countryside than in the city.

I found myself pondering the idea of happiness on the way there – how nobody has a definitive grasp of it. Each of us crafts our own version, shaped by the way we want to live: with freedom and dignity.

Life is private property – it belongs to the one living it. Happiness is hand-made, crafted without a recipe, each time from scratch. The tragic hero in a Greek drama may feel elated even as everyone around him insists he’s doomed. I’ve known people who had it all and still felt miserable. I’ve known people who were afraid of happiness and ran away when things got too good. Too much happiness can be a bad thing.

Happiness is like love – a fire that can warm you or burn you. Best to approach it with care, not go leaping in headfirst. And never trust anyone who wishes you happiness.

One person says “Never change,” another wants you to keep striving. One seeks thrills around every corner, another wants to spend seventy years with his high school sweetheart and die happily in bed on the same day.

Happiness clearly has no nationality.

That’s what I told Michael on the road to Brandenburg.

“Of course, there’s no such thing as some universal British happiness,” he said, “but you can still identify certain cultural tendencies. In general, Brits tend to have a quieter, more contained sense of happiness. It’s often experienced and expressed in a more restrained, subdued way than in Southern Europe or in the Americas. Emotions are kept under wraps. Even big moments of joy rarely get theatrical. The famous British ‘quite nice’ can actually mean extremely pleased. Big emotional outbursts are often seen as rude or over the top. Composure is valued.”

That goes for Brandenburgers too. They don’t like to wear their hearts on their sleeves. You can’t always tell from their faces how they’re doing. When they’re standing behind their garden fence, they won’t greet you. But if they’re in front of the fence and see someone, they always do.

I’d been meaning to bring Michael and the ramp crew to my little village in Brandenburg for a while. We live in what I like to call an invisible village. Dear readers, if you were to drive through, you’d see no one. But the village would see you. Long before you pass the town sign, in fact – the village would have already clocked the British plates on our Aston and Rolls and everyone would be wondering what the English were doing here. Would we all be switching from sausage to fish and chips now?

Sometimes Brandenburgers are hard to understand, but I like them the way they are. They enjoy their self-sufficiency, help each other when needed, are glad when guests visit and not sad when they leave. They’re content with themselves – in other words, “happy as clams”. Here, happiness is often found in small, social moments – while working, gardening, picking strawberries or watching strangers drive by. No wonder that in my book on rural life I renamed our village “Glücklitz” – Happyville. A remote place in eastern Germany where cars are a rare sight. The only road in is a protected historic route that hasn’t been resurfaced in two hundred years. You’d best take it slow on this road.

Our little convoy entered the village, passing through woods echoing with a woodpecker, a cuckoo, wood chippers, combine harvesters and tractors. It was harvest season, the barley had to come in. And every time a massive tractor met a Rolls-Royce in the forest, the driver whipped out his phone for a picture. That’s how unforgettable moments are made. The best photos in life. Most of the tractor drivers were barely out of their teens (I’m guessing you don’t need a license for farm equipment). They’d probably never seen a Rolls-Royce in the woods before. Neither had I.

“British happiness is usually pragmatic and measured,” Michael mused. “Happiness is when things just go smoothly.”

Our cars did too. Despite all the bumps, we made it to the lake in one piece. Even the sporty Aston Martin handled the rough track. We were glad to finally be out in nature. My wife greeted us on the meadow with homemade lemonade and freshly picked strawberries. We laughed about our forest adventure. The classic British “make the best of it” approach – accepting setbacks with a shrug and good humor.

I was starting to get the whole clam thing. Happiness doesn’t come from constant highs but from calm, dignity and persistence. The little things matter: a sunny day, a drive with two beautiful cars, a good cup of tea, a bit of friendly small talk – those can be our happy moments. Quiet contentment. My wife, who spends her summers in the garden, had prepared well for our visit. She’d baked a cake. Sometimes all it takes is a trip to Brandenburg to feel happy.

Human happiness is ambivalent, much like wisdom and reason. The West and the East may define them differently, but there are points of connection, across cultures and religions. Whether Buddhist, Christian or atheist, inner balance has always been the key to happiness – and essential to true wisdom. The great thinkers of the past always spoke with care, calm, irony and poise.

Happiness researcher Michael Uebel, a scholar with the British Psychoanalytic Council, recently wrote that the true key to happiness lies in a flexible and agile mind. Stay open to the new, be ready to play – life, he says, is an invitation to puzzle your way through the world without a final solution. Sounds pretty good to me. Mr. Uebel, you’re now officially my favorite happiness researcher. A certain stubbornness is deeply human – most of us secretly believe we hold the one and only truth. For many people, only two opinions can exist on any issue: their own and the wrong one.

The stubborn ones are always spoiling for a fight. The happy ones are those who can entertain more than two perspectives – and who travel through life like explorers.

That kind of person is open to the unknown. Their world is a wide horizon full of discovery. They want to move through life lightly and find joy in each new insight. This planet has so much to offer, and everyone can find happiness in their own way. There are countless forms of happiness, and we just experienced one of them:

That typically British variety. “Happy as a Clam” – sitting in a meadow in the middle of nowhere with a cup of tea and a glass of lemonade, watching clouds drift by. Not that it’s worth counting clouds in Brandenburg. There are always just two.

Rolls-Royce Spectre

- Powertrain electric motor

- Power 585 hp (430 kW)

- Torque 900 Nm

- Weight 2,850 kg

- 0-100 km/h 4.5 s

- Top Speed 250 km/h

Aston Martin Vanquish

- Engine twin-turbocharged V12

- Displacement 5,204 cc

- Power 835 hp (614 kW) at 6,500 rpm

- Torque 1000 Nm at 2,500 – 5,000 rpm

- Weight 2,005 kg

- 0-100 km/h 3.3 s

- Top Speed 250 km/h

TEXT: Wladimir Kaminer

PHOTOS: Matthias Mederer – ramp.pictures

ramp #68 Happy as a Clam