In 1963, Ford of America announced it was about to break a long-standing agreement amongst the ‘Big Four’ automobile manufacturers that prohibited then from competing in motorsport in an official capacity. Ford’s original intention was to go racing via a third party so an approach was made to purchase Ferrari at a time when Enzo Ferrari was considering selling his company in a deal that would allow him to concentrate on racing.

As talks progressed, Ferrari began making numerous demands which led Ford to realise that any form of agreement would prove impossible. In response to Ferrari’s political manoeuvres, Ford took the decision to tear up the non-racing agreement and build its own GT sports prototype to take the fight to Ferrari, specifically to overturn the Italian team’s domination of the Le Mans 24-Hour classic.

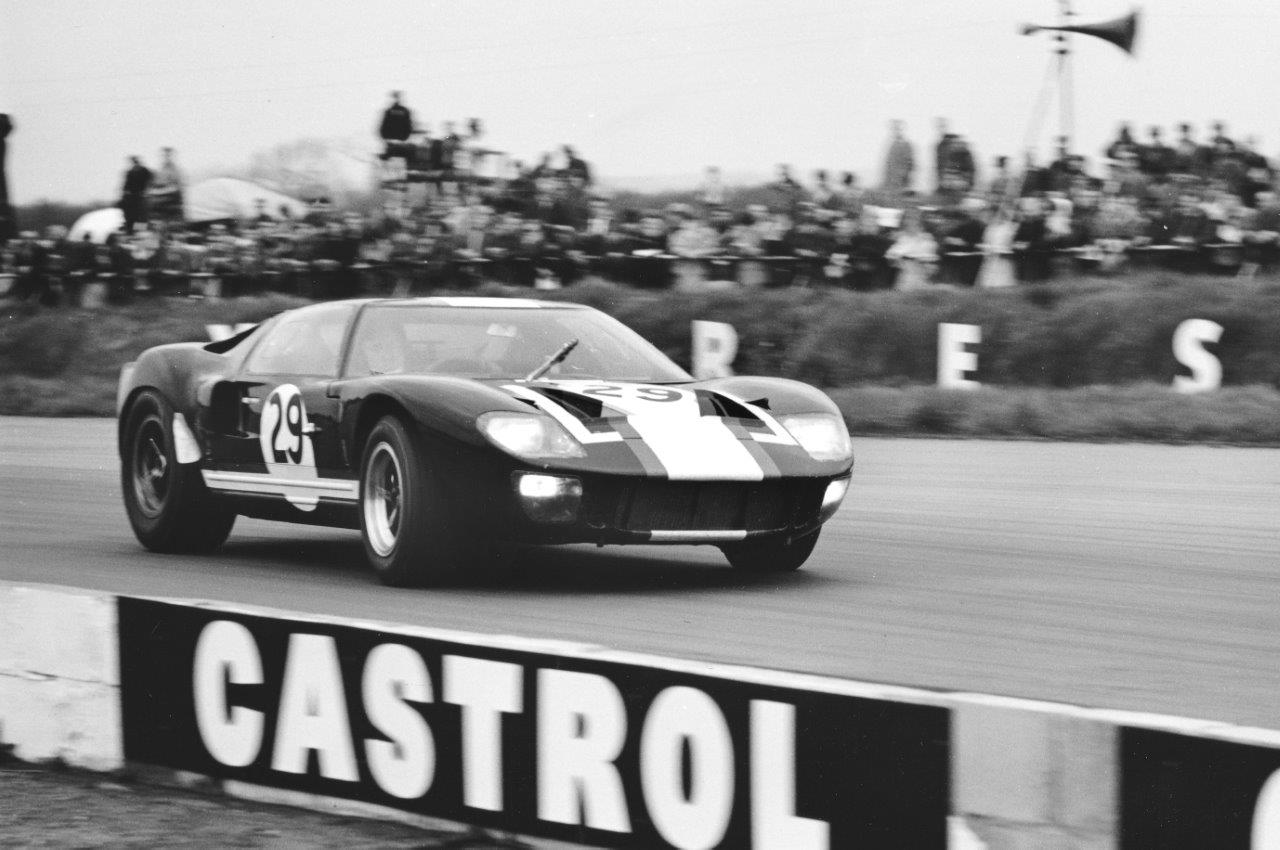

Despite the fact that very few people within Ford’s Dearborn headquarters had ever heard of Le Mans, the project got underway backed by a virtually unlimited budget. The senior heirachy at Ford naturally expected immediate results but history records they learned a lesson about racing the hard way. During the first two seasons, in 1963 and 1964, the Ford GT (which became better known as the GT40), retired with monotonous regularity, failing to record any meaningful results. Once the Shelby American team engineers were tasked with turning the car into a race winner for the 1965 season, reliability showed a dramatic improvement with victory at the first race of the season as the GT40s came home first and third at Daytona followed by a second place at Sebring, but once again Le Mans proved a disaster with all six cars retiring. The Ferraris remained competitive and capable of winning but they were being made to work for it.

From 1965, once race preparation moved to the USA, Ford Advanced Vehicles, based in the UK, began construction of a minimum of 50 road and race GT40s to qualify for the new Group 4 GT category (instead of the usual ‘Prototype’ class). First to take delivery was F. English Ltd of Bournemouth, a large Ford dealership owned by Colonel Ronnie Hoare who also owned Maranello Concassionaires, the largest UK Ferrari importer. Chassis number GT P/1002 was delivered on May 13th and entered its first race three days later. It was joined by P/1017 later that year. In August the French team Ford France took delivery of P/1007 followed by P/1020 in November. Ex-motorcycle racer Guy Ligier decided to change to sports car racing and took delivery of P/1003 in May 1965 having reached an agreement to race under the Ford France banner with the team supporting and preparing his car. Private teams in the USA were also eager to obtain GT40s for club and international events, especially Skip Scott who created the Essex Wire team and took possession of P/1010 on August 23rd 1965. He planned to compete in European races during 1966 including Le Mans and over the course of two years purchased three more GT40s.

It was the privateers that helped promote the Ford name at numerous events around the world as well as picking up the occasional world championship point to assist the works effort. The first victories were recorded by Ford France at club racing level as well as the very popular European hillclimbs, such as Mont-Dore where the owner of P/1003, Guy Ligier, won outright in August 1965. In the UK the first private individual to convert to the GT40 was Peter Sutciffe who had P/1009 delivered in kit form to South Africa where he took part in the winter Springbok racing series, recording three wins and several podium places. In 1966 he sold the car and replaced it with the FAV roadster P/112. However the most successful private entrant was the Australian driver Paul Hawkins who bought a lightweight GT40 from the Alan Mann team that carried the chassis number AMGT-2. Mann considered the GT40 to be too heavy (it was no lightweight) so rebuilt a pair of GTs using thin-gauge steel and aluminium. To qualify as a Group 4 entry, Hawkins had to replace the body panels and doors with heavier fibreglass but ‘forgot’ to modify the roof structure by covering it in a very thin gauge steel to pass scrutiny. Originally painted dark blue, it was later returned to its original red and gold colour scheme to became the most famous GT40 as Hawkins went on to win races around Europe and the UK.

Amongst some 70 small teams and ‘gentleman drivers’ who decided to race a GT40, an honourable mention should go to two individuals; William Wonder from New York and Karl Richardson from Essex. Flight engineer Bill Wonder was looking for a car to race in 1966 when Ford offered him P/103 at a very low price. He took the opportunity and entered the major national and international races in the USA and was still competing in 2004, sharing the car with his son. In the UK, Karl Richardson took delivery of P/1014 in September 1965 and initially used it as a road car, becoming a common sight around the country roads of Essex and even gaining a mention in the national press. In July 1966 he entered it in the Mont Ventoux hillclimb on the island of Jersey where he finished second to P/1003 driven by Guy Ligier. This was followed by an appearance at the Brighton Speed Trials later that year. In June 1967 the car once again competed at Mont Ventoux before being sold the following month.

By the end of the 1960s, race car design and aerodynamics had moved on leaving the GT40 behind. The cars were sold to collectors and individuals who, throughout the 1970s and 1980s continued to find suitable race categories in which to to compete, generally at club level as well as sprints and hillclimbs. As historic motorsport gained in popularity, demand for the limited supply of original GT40s grew as the category evolved into a highly competitive form of motorsport. The versatile GT40 was both fast and relatively uncomplicated to repair which appealed to would-be race drivers and collectors alike, qualities that gave rise to a demand for replicas. The value of the GT40 has continued to rise unabated over the decades, prices dependant on condition, originality and race history, especially as they became one of the most sought-after race cars, one that allowed entry to the highest levels of historic racing. Fortunately for motorsport enthusiasts who were not around to witness the battle of Ford verses Ferrari back in the day,we are still able to witness GT40s being driven to their limit at circuits such as Nurburgring and Spa as well the Goodwood Revival which always attracts a large GT40 entry.

It is difficult to believe the timeless and versatile Ford GT40 is now 50 years old; almost all are still either in collections or being actively raced and enjoyed as they deserve.