Over a half century, I’ve almost done everything I wanted with motorcycles. I built, raced, and restored them, commuted and toured, rejoiced in getting them dirty, and reveled in their preservation. Along the way I loved the great ones and loathed the lame ones. And when sleep wouldn’t come, to quiet the brain I designed the ultimate shop with a lift, benches, and tools, and I imagined which bike I’d tackle first and how I’d do it. Someday, that would be my Zen.

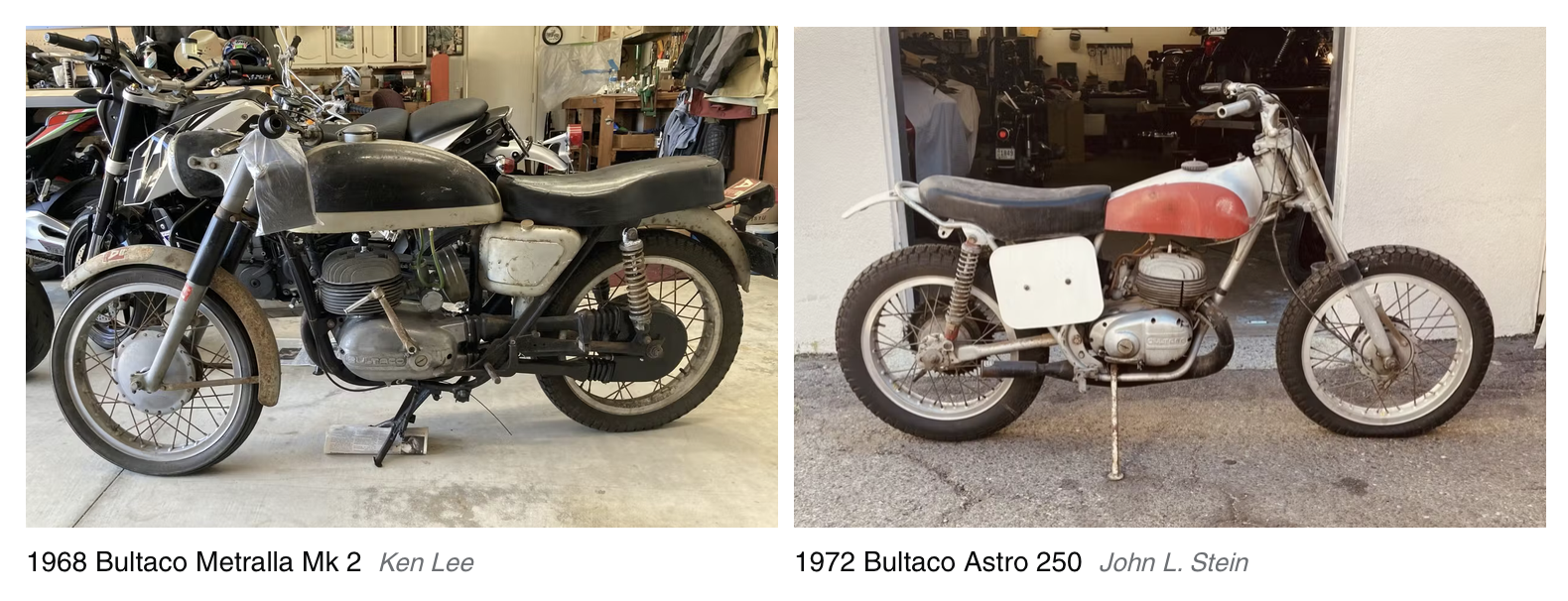

The time was supposed to be retirement, whenever that occurred. This is partly why I’d carefully tucked away five favorites in a borrowed garage, to await my emancipation from the working world. The oldest was a 1950 Norton International Model 30, a potent overhead-camshaft roadster resembling the English factory’s Manx racing bikes. The newest was an English/Japanese hybrid, a 1987 Harris Magnum 2 chassis housing a fuel-injected Kawasaki GPz1100 engine. In between were a 1959 Matchless G50 grand prix bike, one of approximately 180 made; a 1968 Bultaco Metralla Mk 2 sport bike; and a 1972 Bultaco Astro 250 flat-tracker. I’d collected them all over two decades.

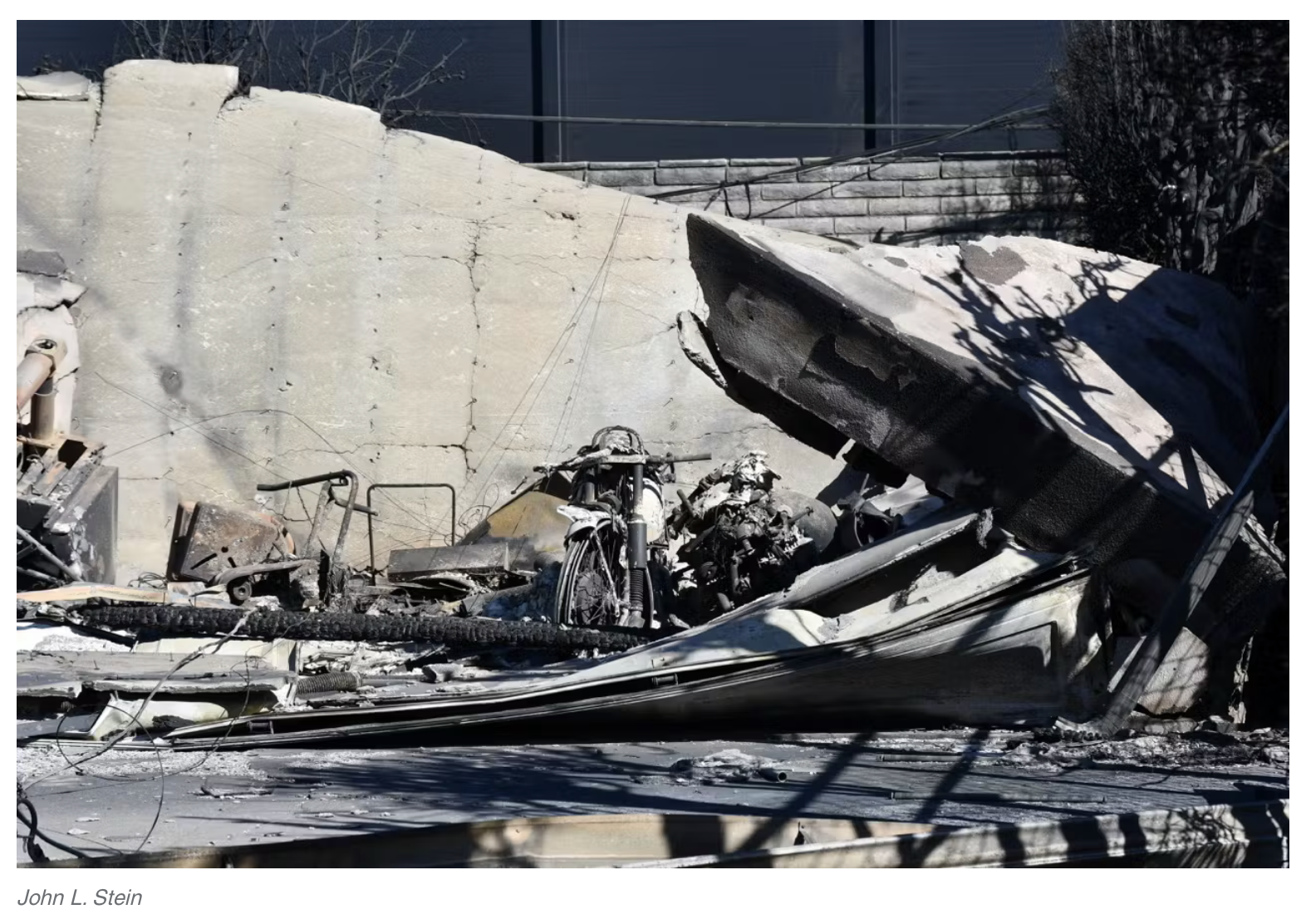

As you have probably already guessed, based on the accompanying photos, the plan went up in flames. Stored in Pacific Palisades, California, they never stood a chance when a historic firestorm ripped through the community on January 7–8, 2025. Reportedly the costliest blaze in LA history, it destroyed more than 6800 homes in a raging path of destruction from the hills through town to the Pacific Ocean. The idyllic coastal community, essentially, was gutted.

A few days later, I was able to access the property to assess the situation for this report. Properly credentialed, I cleared National Guard and police checkpoints and made my way through the devastation. Having seen aerial photos online, I steeled myself for what I might witness. What I found, though, was far more than high-altitude photos could reveal. The streets were completely deserted, with not a soul seen, excepting a few firemen and police making the rounds. “War zone” comes to mind.

Most houses had literally burned to the ground, with only chimneys and the occasional steel frames or garden walls remaining. Anything combustible had been incinerated. The precious few homes that remained were a mystery in that they looked all but undamaged despite being surrounded by destroyed ones—up to 75 percent of the community, by one estimate.

Abandoned cars were burned out, their aluminum components like wheels melted into pools on the streets. At ground level, the carnage was breathtaking, but my mind was in another gear—grim focus and a commitment to not do anything dumb, such as tangle with a downed powerline or run over tire-flattening debris. “I’d be safe and warm if I was in LA,” sang The Mamas & The Papas in ’65. “California dreamin’ on such a winter’s day…” Not here. Not now.

Making my way slowly to the address in a nearly catatonic state, my brain struggled to comprehend what I was seeing, but I knew it was real. Along with the expensive homes (the median price in Pacific Palisades had been $4.2 million), another thing missing was color. Everything—streets, structures, foliage, dirt—was reduced to depressed shades of gray, black, or brown.

Once I reached the address where the bikes were kept, I stepped out of my car and was amazed to note almost no smell of fire. I’d been in brutally pungent fire zones before, so this was perplexing. Also curious was that so soon after the fire, clear pastel skies lazed overhead, the quiet blue Pacific shone in the near distance, and benevolent temperatures and kind sunlight mingled with barely a whisper of breeze. More unexpected was the silence, with only the distant thrum of a helicopter or fire engine on patrol.

And crows.

The only animals around, the birds seemed unperturbed, cawing and soaring through the area like it was just another day in a Hitchcock flick. With eyes closed, there would be no evidence of what happened here.

Knowing that fire areas can be dangerous, I brought a respirator and goggles, heavy jeans, huge motocross boots, and leather gloves. Gearing up at the street, I looked up the long driveway toward the garage and froze. The structure was gone, as feared; only its concrete foundation remained, along with portions of its stucco walls, now collapsed. But in the middle appeared the front wheel of the Norton. It had burned on its stand and remained upright, as had the other bikes—or at least what I could see of them. Now it appeared to be looking for me.

The Norton was recognizable as an overhead-camshaft model thanks to melted aluminum castings, which revealed the straight-cut bevel gears. Also visible was the iron cylinder, but other alloy parts had either pooled beneath the bike or partially melted. Of course, organic materials such as grips and saddles were gone. Tinware like the headlight and front number plate had dropped away, and the wheel hubs and aluminum Roadholder fork had fallen to pieces. It was heartbreaking, as the bike, previously owned by noted Stanford engineer Thorwald van Hooydonk, was a concours winner.

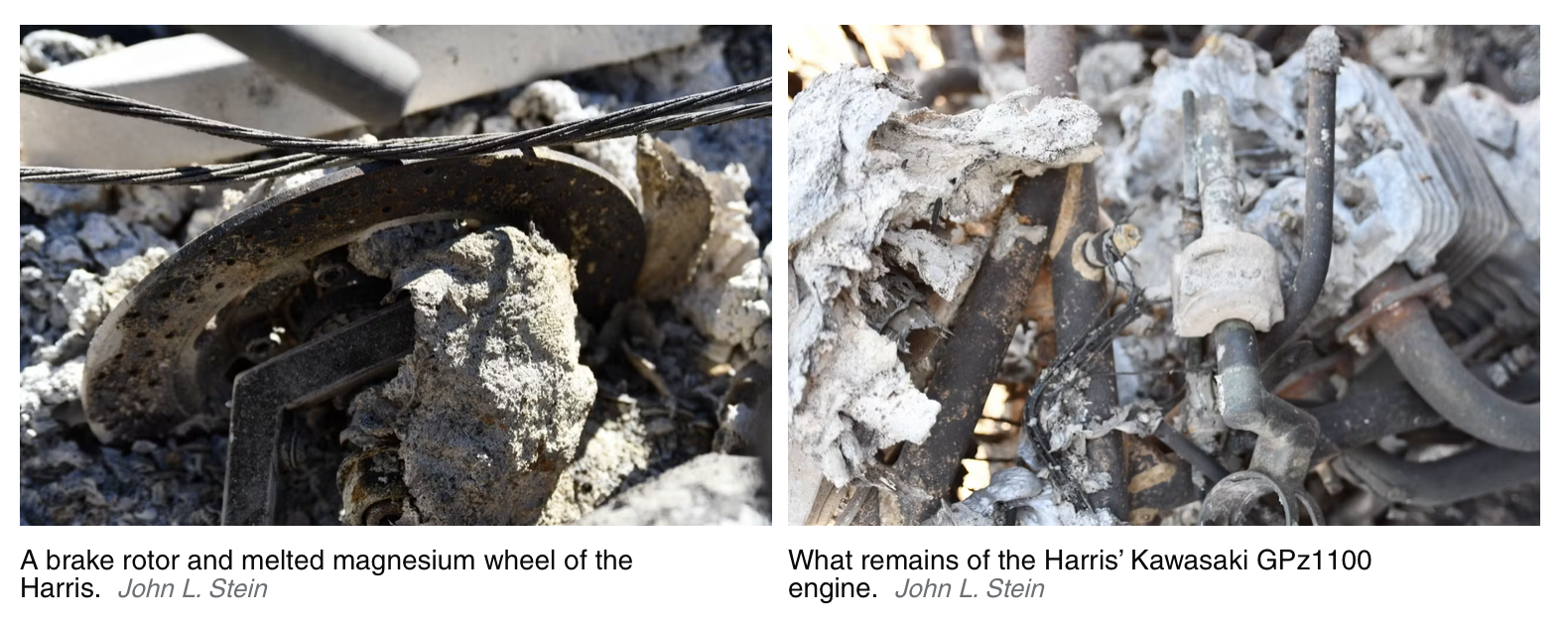

Beside the Norton stood the poor Harris, which had been built for Bob Sinclair, former president of Saab-Scania USA. It was almost unrecognizable as a motorcycle. Its quick-fill aluminum fuel cell, inverted fork, and shock body were gone, as were the magnesium wheels. Fire found the fiberglass, naturally, and devoured it instantly. It had been so hot that the frame’s bronze-welded steel tubes had simply fallen apart as the filler melted. (For reference, silicon bronze melts at 1880 degrees Fahrenheit, while aluminum and magnesium melt just above 1200 degrees and steel at 2500–2800 degrees.) Even had I been on site, that kind of heat made the odds of defending the garage infinitesimal—it likely would have been a “your bikes or your life” situation. This saddened me because Sinclair had been a good friend, and I promised his family that I’d care for the machine after his passing in 2009.

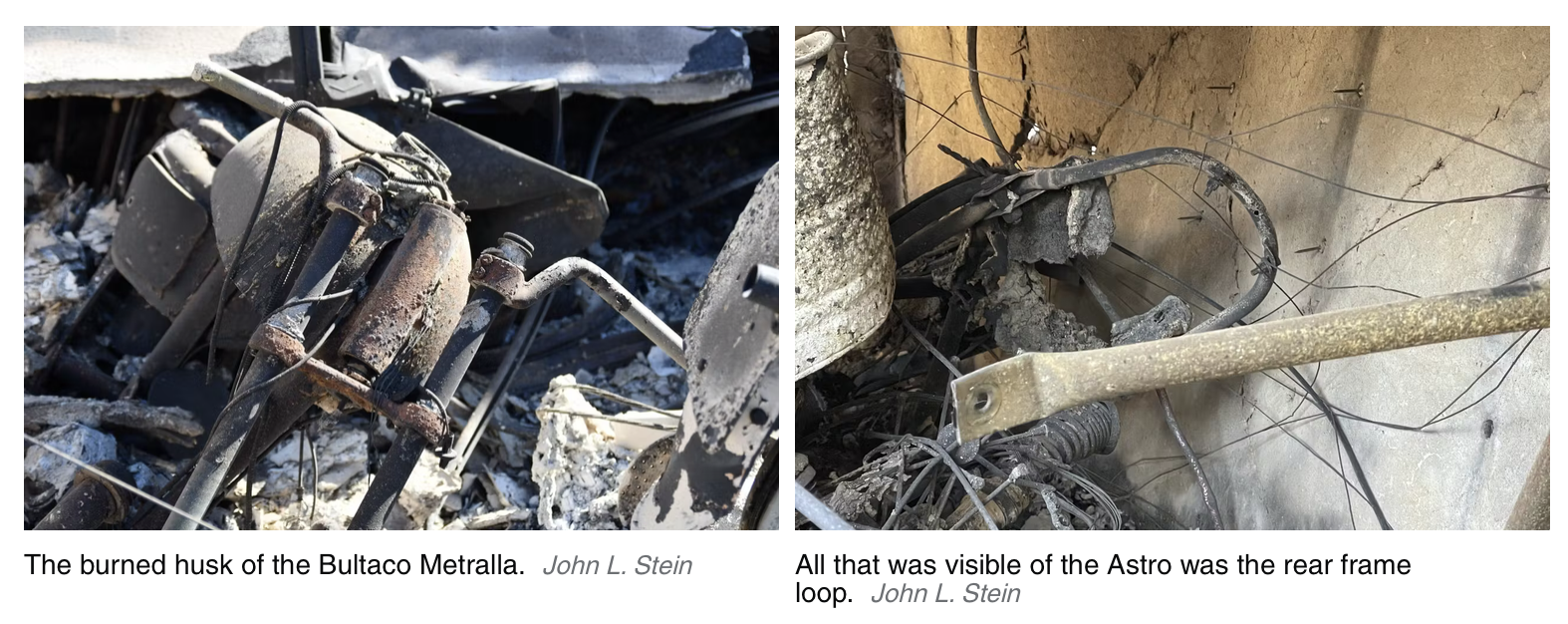

The carnage continued with the Bultaco Metralla. Regarded as one of the brightest small-displacement street bikes of the 1960s, this Spanish two-stroke 250 was light, lithe, torquey, and impeccably styled, the organic shapes of its bodywork, engine, and exhaust blended masterfully. I’d wanted one for decades and was thrilled to land this survivor in 2022, the perfect counterpoint to a Ducati 250 Diana I’d been saving. The loose idea had been for my racer friend Randy Pobst and me to tour to The Quail MotoFest on the pair sometime. But the Bul was now scrap. Its alloy engine had melted into a blob, and the fork legs were gone, leaving the springs exposed like ancient gargoyle claws, and of course the paint, tires, and saddle were toast.

The news was probably worse for the Astro flat-tracker, but I couldn’t see beyond the rear frame loop, which was barely visible beneath a section of wall that had collapsed inward as the studs burned through. The dirt racer had likewise held a certain hope for me, now unfulfilled. Soon after I started racing at 18 years old, I’d been offered an Astro ride at a half-mile oval event, but honestly, the powerful bike intimidated me, and I wimped out. Likewise found in 2022, this one was going to square things up, with my intended article entitled “Meeting Darth Vader.”

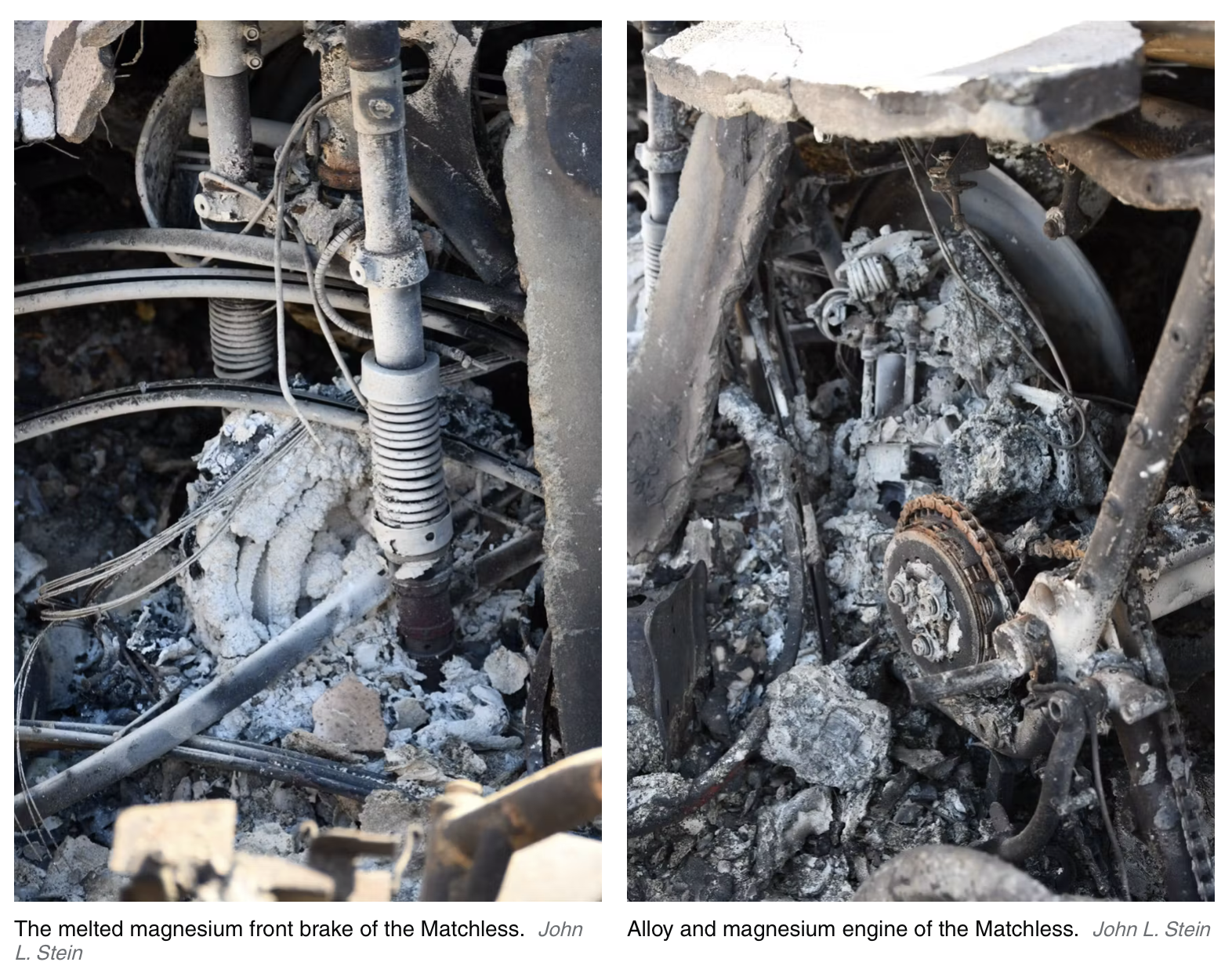

Besides the ruined Norton and Harris, most depressing was the Matchless G50. An exotic overhead-camshaft British single, it was a genuine GP contender in period, equipped with magnesium engine cases, hubs, and brakes and a sensationally large aluminum tank for long races like the Isle of Man. They were well regarded but rare, and today various firms reproduce G50 engines, gearboxes, and other components for classic racing. Previously owned by South African friend Michael D’Oliveira and his father, it had a robust career there prior to my acquiring it in 2002. I failed them, too, as fire devoured the plentiful magnesium and alloy—which made up a greater percentage of this machine than the other bikes. Steel frame and mechanicals aside, the G50 had literally melted.

All of the bikes were insured through Hagerty, and once it registered there was nothing to save, I sent photos to a claims agent, who deemed all bikes totaled and ordered checks to be issued. The process spanned 16 days from loss to payment, a far cry from the insurance mess through which so many homeowners are still wading, but it gave me a chance to inform the previous owners what had happened. Doing so helped me realize that because motorcycles are not people or pets, the loss takes on a different feel. And since I hadn’t ridden the bikes yet, it wasn’t like losing long-term companions. Instead, I felt the loss of expected future enjoyment, sadness that some classics were irretrievably gone, and regret at having failed my friends. There were no words I could use other than “I’m so sorry.” And I really am.

It’s said that when nothing else can replace a loss, money helps. Somehow, I don’t think it will that much. Although maybe I do need to find myself a midyear Sting Ray, a Jeep CJ-2A, a Taco minibike or something …

We will see.

Report by John L. Stein for hagerty.com