There are few more evocative sounds in the world of motorsport than the screaming V-8 of a Lancia LC2—a car that lit up Group C with its blistering performance, stunning organic coachwork, and unparalleled Italian flair.

The ethereal howl of its fearsome Ferrari-derived engine at full chat was enough to humble even its fiercest rivals while providing a spine-tingling, unforgettable soundtrack for those fortunate enough to line the track at Imola, Silverstone, and Le Mans during the height of its powers.

- One of three Lancia Works cars built to contest the 1983 World Endurance Championship

- Two-time 24 Hours of Le Mans entrant; finished 6th overall in 1985

- Winner of the 1983 1000 Kilometres of Imola; podium finisher at Mugello and Kyalami

- Fully restored by Canepa of Scotts Valley, California, between 2015 and 2016

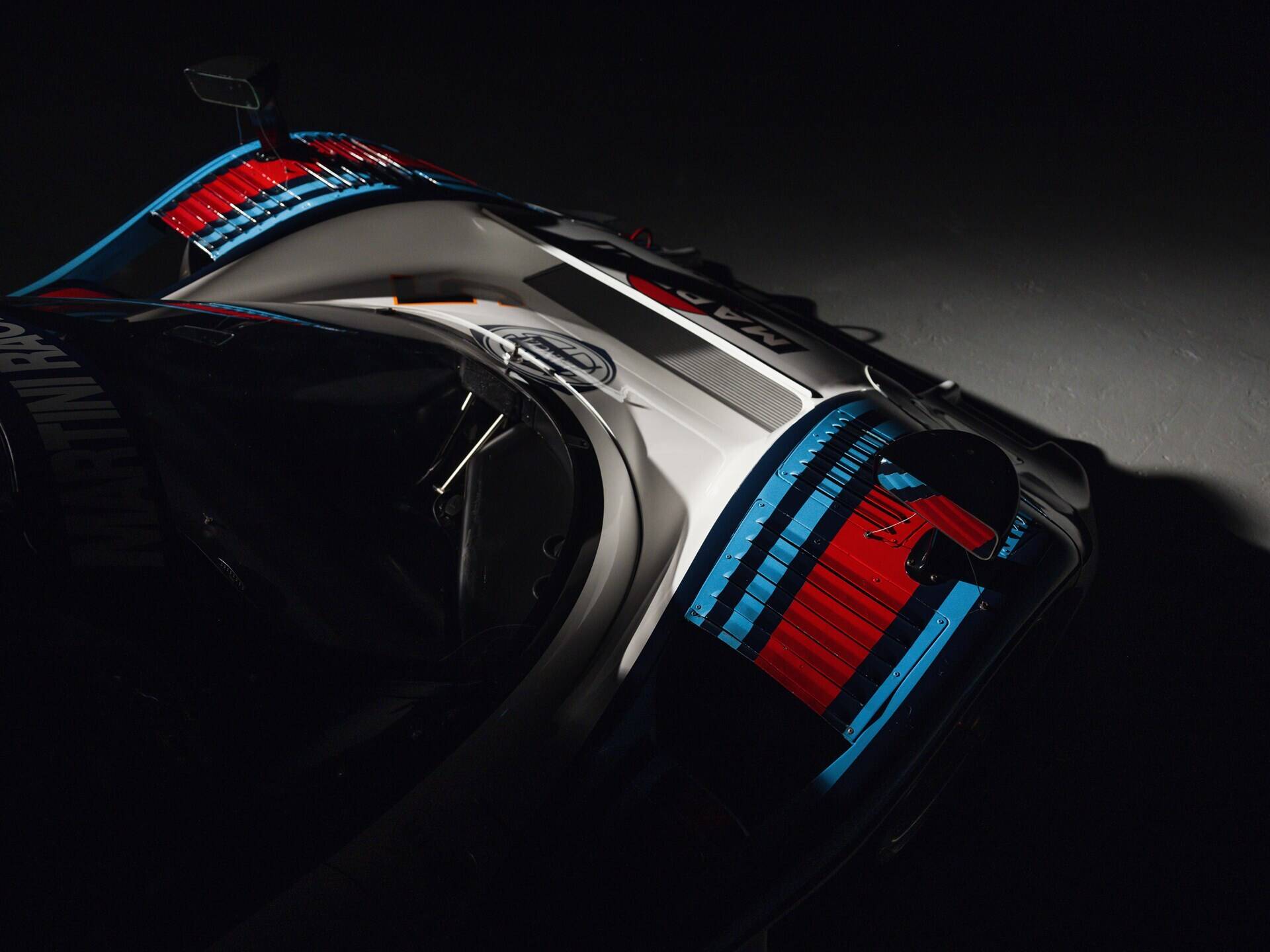

- One of only seven factory-built LC2 chassis produced; presented in the more attractive 1985 body configuration

- Accompanied by a Lancia Certificate of Origin, restoration binders, and assorted spares

- Price Upon Request

Though Squadra Corse undoubtedly had its greatest success on the loose, with an enviable record at the great rallies of the day—the Mille Miglia, Targa Florio, and Carrera Panamericana, not to mention the International Championship for Manufacturers and its World Rally Championship successor—the Red Elephant also proved a big beast in circuit racing. Between 1979 and 1981, the Italian manufacturer swept aside all comers thanks to the brilliant Beta Montecarlo Turbo. But the winds of change were blowing, and following Lancia’s victory in the 1981 World Endurance Championship for Makes, the FIA introduced Group C regulations for sports cars.

Lancia stepped into the new arena with an open-topped prototype built to Group 6 regulations, and while not being held to Group C fuel restrictions allowed Martini Racing to run the fire-breathing 1,425-cc ‘four’ flat-out—snatching three pole positions from eight races in the process—the LC1 was incapable of bridging the 200-horsepower power deficit to the Porsche 956. Ultimately, just four were built.

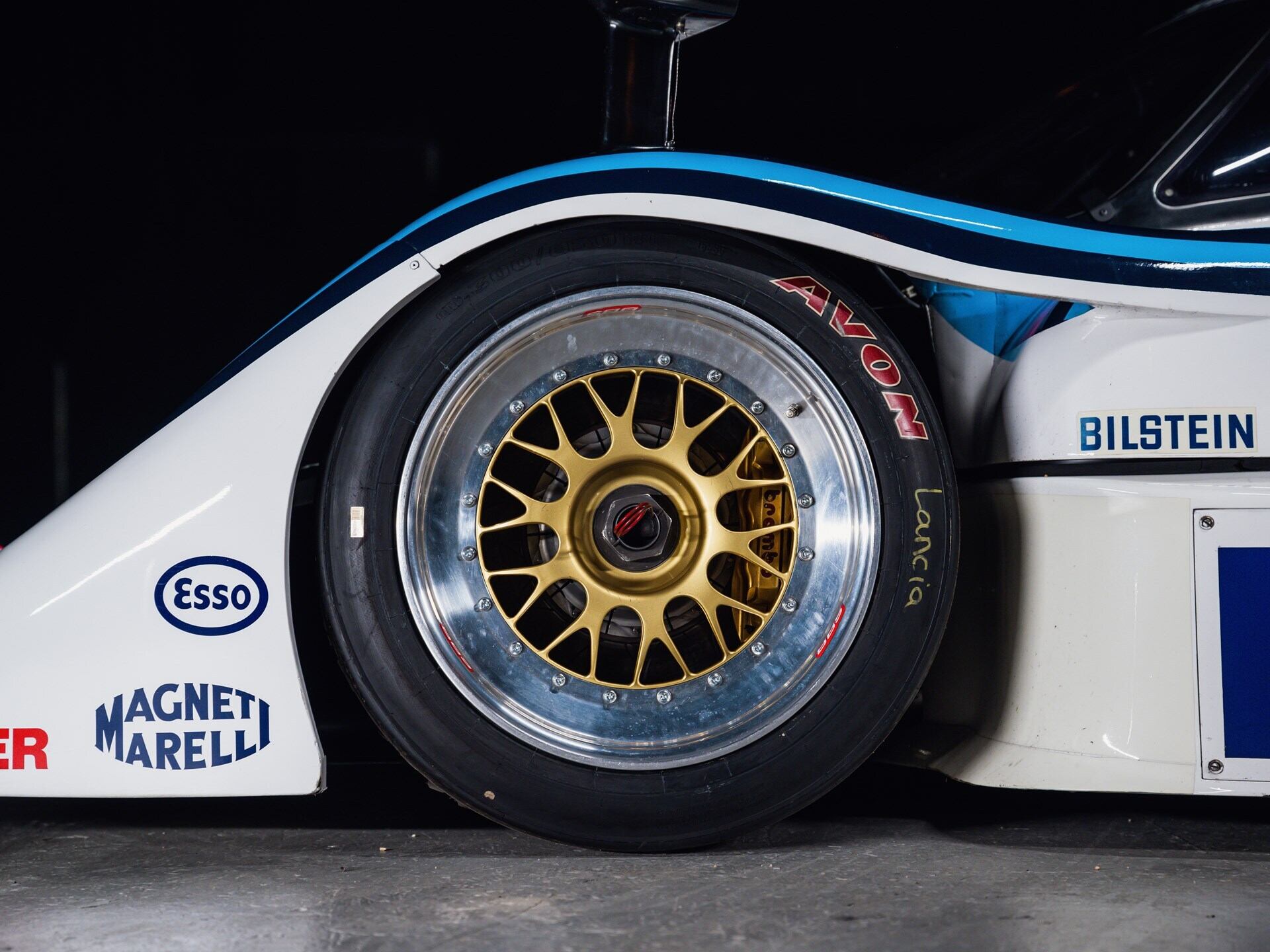

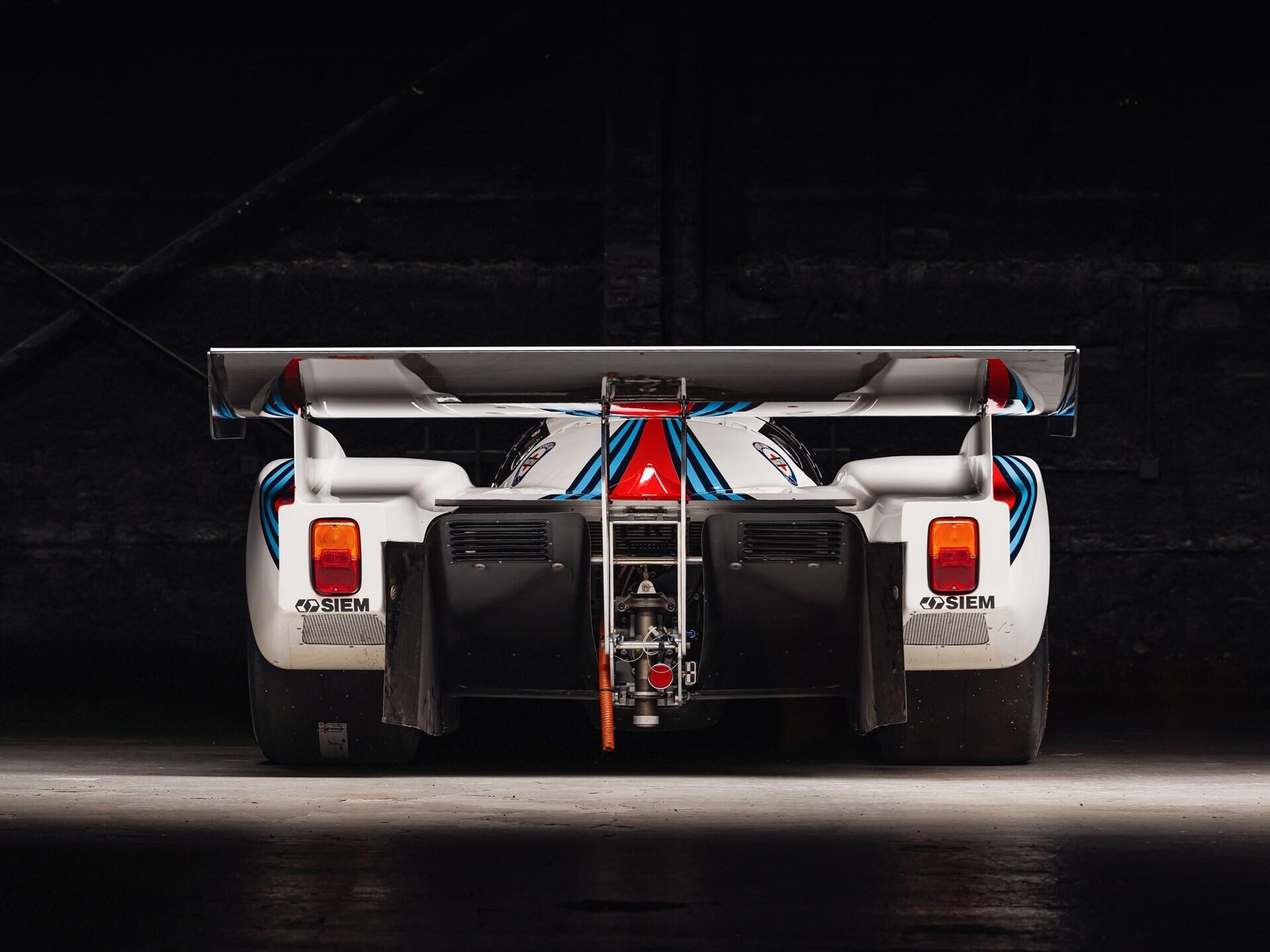

To take the fight to Porsche, Lancia needed to up the ante and develop a bespoke Group C racer: the LC2. Like its predecessor, the LC2 owed its striking design to Gian Paolo Dallara, who devised an ingenious chassis constructed from Avional—a lightweight fusion of aluminum and copper—formed in a honeycomb structure with additional reinforcement from magnesium ribs. The pilot was housed in a safety cell comprised of Inconel panels and a titanium roll bar, while the incredibly slippery and breathtakingly beautiful coachwork made extensive use of carbon fiber and Kevlar.

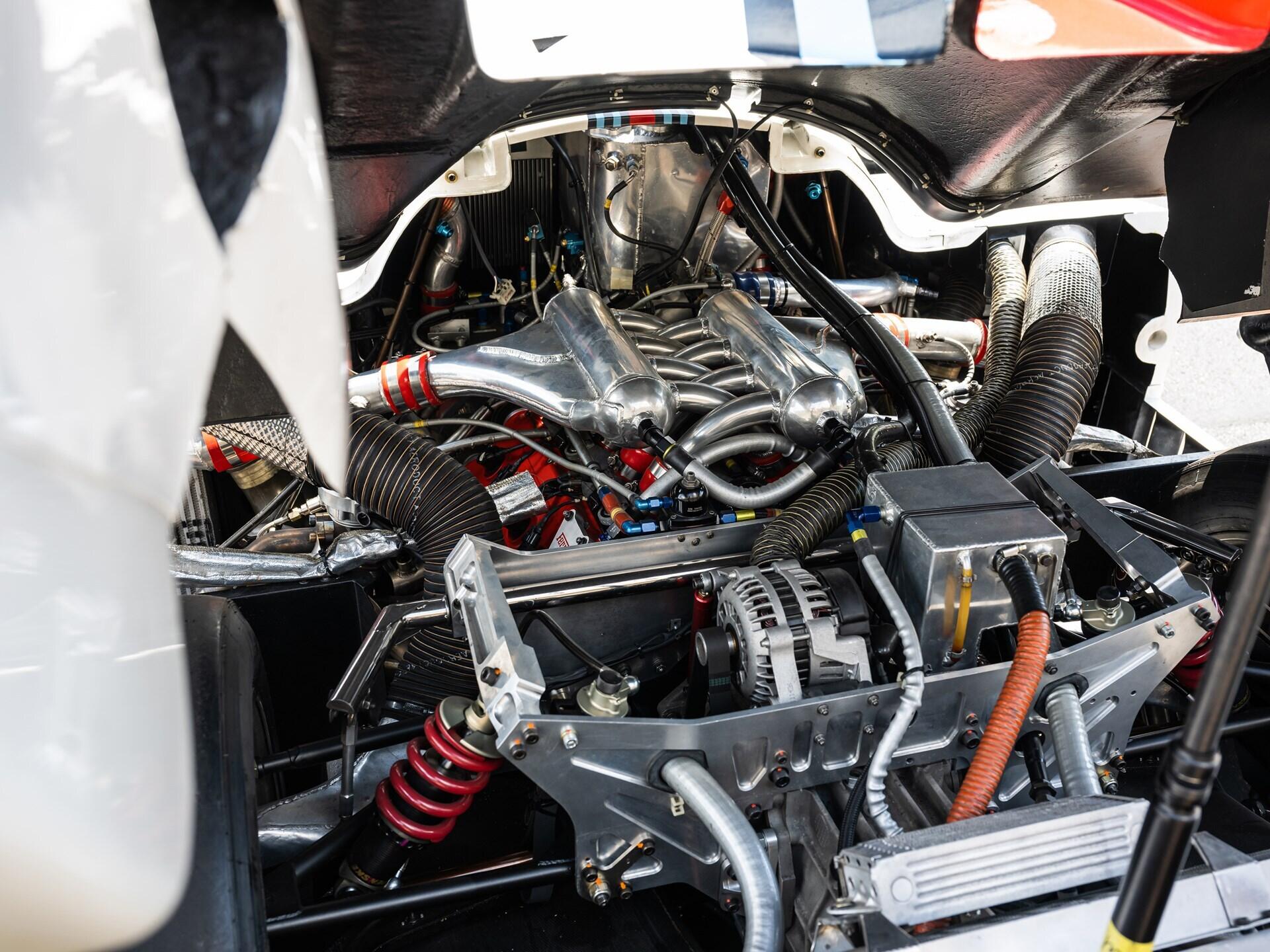

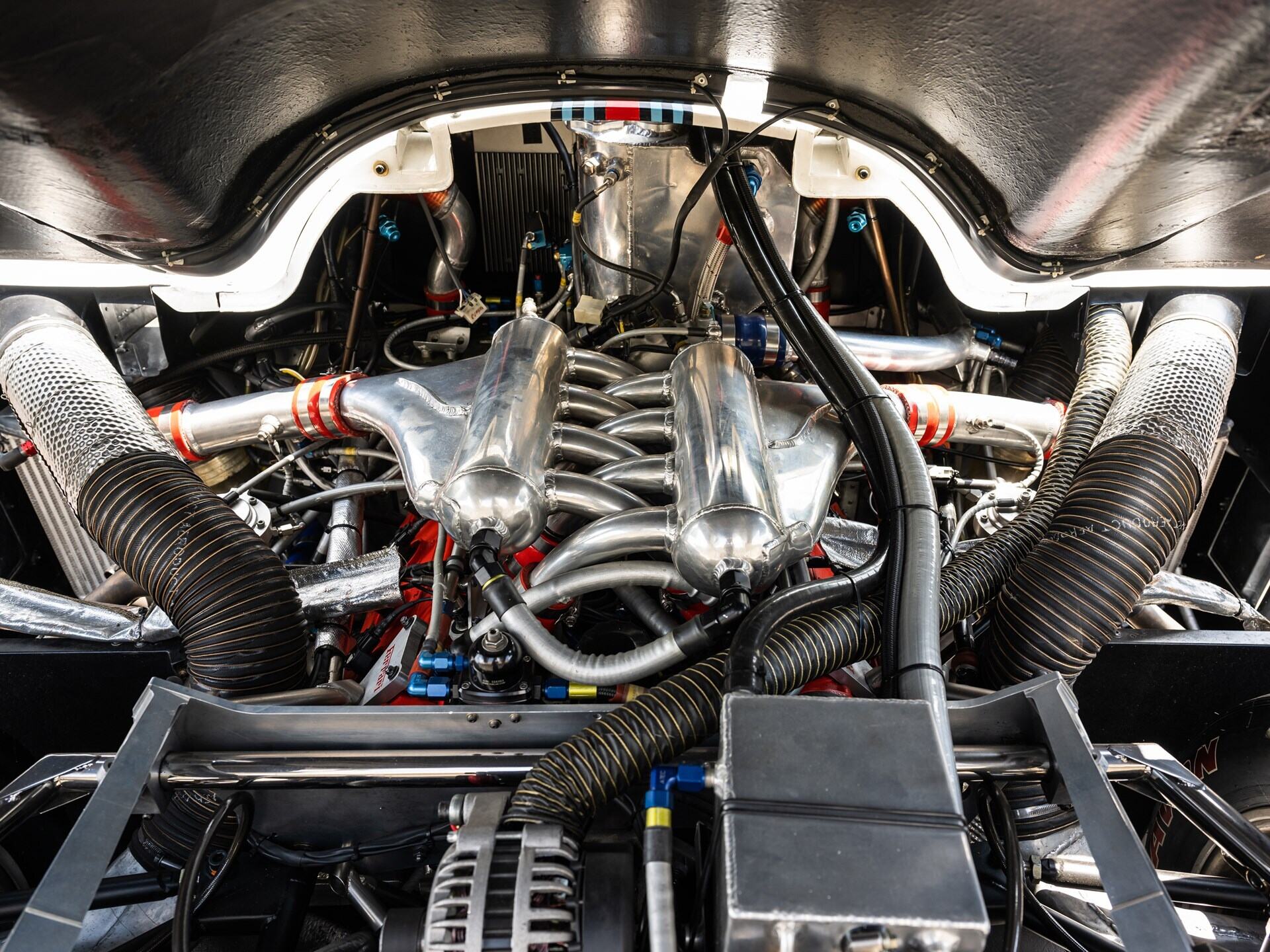

The LC2’s party piece was undoubtedly its engine, which not only bridged the gulf in power to the Porsche 956 but arguably gave the striking racer its unmistakable character. Echoing the marriage of Lancia design and Maranello power that brought the Stratos such success, the incredible twin-turbocharged, 2.6-litre double overhead-cam V-8 engine was the product of a collaboration with Ferrari and would also find a home in the 288 GTO. Hand assembled by technicians at Abarth, the unit was capable of producing a staggering 700 horsepower while spinning to a dizzying 9,000 rpm. Combined with the otherworldly streamlined coachwork and a curb weight of only 850 kilograms, the LC2 was able to achieve speeds of 360 km/h—enough to challenge for honors everywhere from Monza to the Mulsanne.

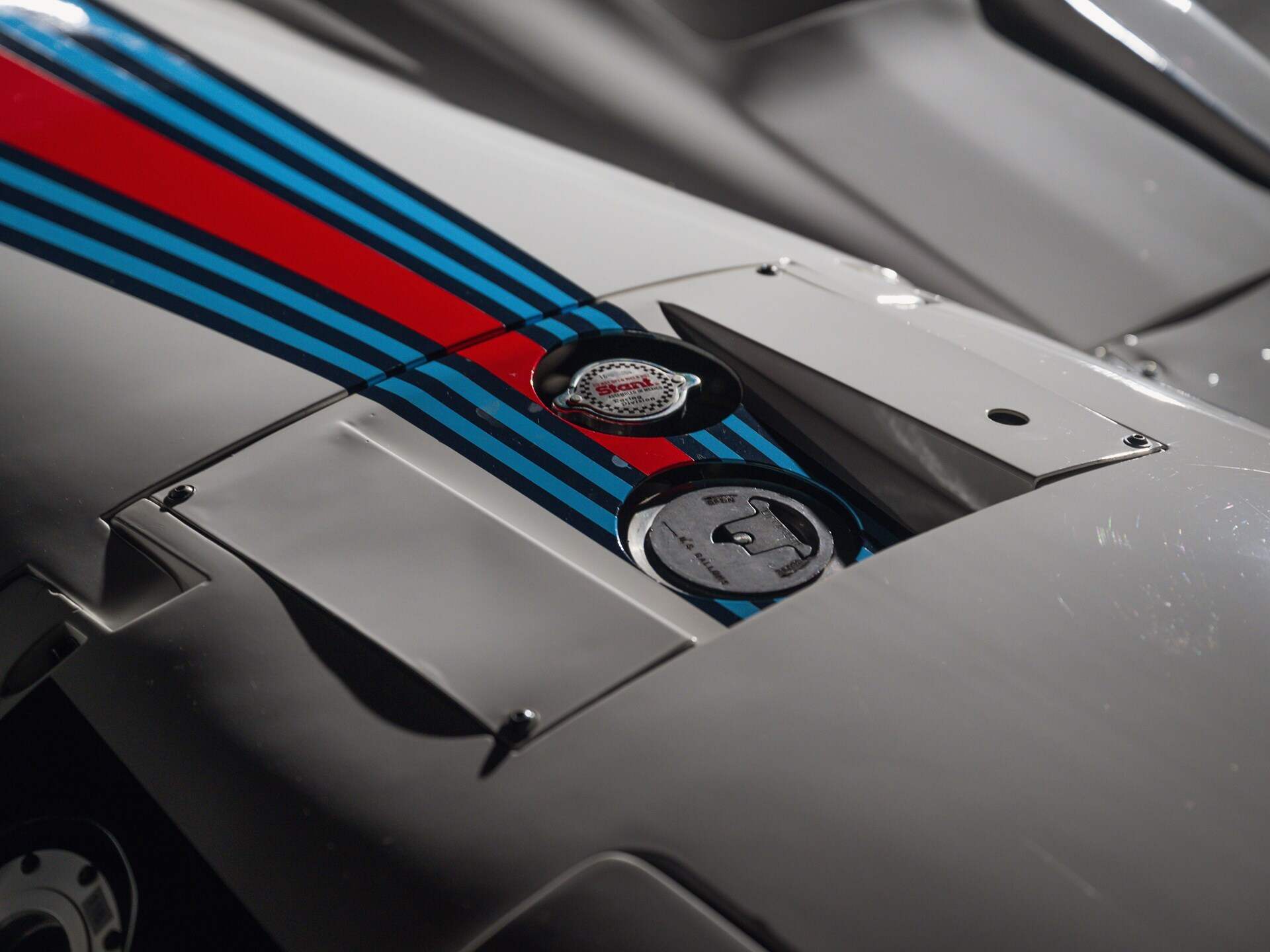

Lancia initially constructed four LC2s to contest the 1983 World Endurance Championship, with the first three becoming Works cars and the fourth supplied to Scuderia Mirabella. The car offered here—chassis 0002—is just the second to be built, and formed part of the special trio that was campaigned by the factory wearing the now iconic red, white, and blue livery of Martini Racing.

The model’s race debut came at the 1000 Kilometres of Monza on 10 April 1983, and while Porsche fielded no fewer than nine 956s, all eyes were fixed firmly to the streamlined newcomer from Lancia. Chassis 0002 was driven by Michele Alboreto and Riccardo Patrese, wearing race number 4, while its sister car, 0003, was given to Piercarlo Ghinzani and Teo Fabi and wore number 5. The new racers immediately showed their fearsome pace in free practice, and though Ghinzani struck the barriers in chassis 0003, repairs were made, and he placed the car on pole the following day, ahead of the Joest Racing Porsche 956 of Bob Wollek and Thierry Boutsen. The race result was more disappointing, with both cars proving too much for the as-yet untested Pirelli tires; chassis 0003 retired with a puncture, while Alboreto and Patrese brought chassis 0002 home in 9th place. Despite the final standings, the experiment was a success, proving that the new model had a potentially race-winning turn of pace and firing a shot across the bows of Lancia’s closest rivals.

The same driver pairing was retained for 0002’s next outing at the 1000 Kilometres of Silverstone on 8 May, but while the car qualified 4th, it failed to make the distance; both LC2s were forced to retire having overheated. It was a similar story on 29 May at the 1000 Kilometres of the Nürburgring, where the car qualified 6th—now sporting Dunlop rubber—but retired when its differential failed. Lightning struck twice, and the same fate befell the Scuderia Mirabella entry.

On 16 June, a full complement of three Lancia LC2s—0001, 0002, and 0003—lined up to contest the greatest prize of the year: the 1983 24 Hours of Le Mans. With the Porsche 956s having remained unbeaten all season, the task facing Alboreto, Fabi, and Allessandro Nannini could not have been greater. A blistering qualifying pace that delivered 2nd position on the grid behind the Works 956 of Jacky Ickx and Derek Bell gave them the best possible chance, and for the opening 10 laps of the French epic, 0002 battled tooth and nail for the lead of the race. Sadly, the team did not make it to nightfall, with gearbox problems forcing their retirement at 6 p.m. The sister car of Ghinzani and Hans Heyer fared little better, giving up 3rd position due to ignition problems. Once more, the Lancia LC2 had given a glimpse of its pace—regrettably, also its reliability.

A month later, on 3 July, Hans Heyer was given sole driving duties for an outing at the 200 Miles of Nürnberg in his native Germany, where a failed rear axle put paid to his chances after qualifying 4th; the car was withdrawn from the second race of the day. However, by the following month, things had finally started to turn around, and the team began to string together some impressive results, starting with a 7th-place finish at the 1000 Kilometres of Spa on 4 September—only the car’s second finish since its debut at Monza. Things only got better a fortnight later, when Alboreto and Patrese brought the car home in 4th position at a very wet 1000 Kilometres of Brands Hatch, having battled their way up from 8th on the grid.

Two solid performances abroad provided a boost for the team and a springboard from which to return to home soil in October. In the absence of the Rothmans-liveried Works Porsches, the LC2s lit up qualifying with Nannini and Beppe Gabbiani putting 0003 on pole, followed by Fabi and Heyer in 0002. A stellar performance in damp conditions saw 0002 take a triumphant 1st position, leading a chasing pack of five Porsche 956s by an entire lap. The race marked the first-ever win and podium finish for a Lancia LC2. Martini Racing continued its run of form later that month, with Patrese and Nannini qualifying 4th in 0002 for the 1000 Kilometres of Mugello on 23 October, and storming to a 2nd-place finish behind Wollek and Stefan Johansson’s Joest Racing Porsche 956.

The same driver pairing brought 0002 home in 2nd place at Kyalami on 10 December, though arguably, it was a more impressive result. In South Africa, the team had to contend with a brace of factory-backed Rothmans-Porsches that had locked out the front row of qualifying, resulting in Nannini and Patrese starting from 6th on the grid. Nothing short of a battling full-blooded drive would do and, against the odds, the Martini-liveried racer split the Porsches at the checker, finishing a full four laps clear of the 3rd-placed 956 of endurance racing legends Jochen Mass and Jacky Ickx. The race was the final outing of the season, and a resounding “mic-drop” moment to those who still questioned the LC2’s reliability.

For the following year, chassis 0002 was temporarily retired. It played no role in what became another mixed season, with the best result coming at the end of 1984 with a 1-2 finish in the final round at Kyalami.

The car made its return to the track on 14 April 1985, its bodywork revised and its 2.6-litre Nicola Materazzi-developed engine having been replaced by a 3,014-cc variant married to Magneti Marelli engine management. Fitted with twin KKK turbochargers, the new engine targeted similar levels of fuel consumption to the outgoing unit, but with total output now approaching a scarcely believable 840 horsepower in qualification trim. The Lancia proved unstoppable in qualifying, lapping Mugello a full second and a half quicker than the fastest Rothmans-Porsche and capturing a dominant pole position. Problems with the new engine forced its retirement from the race, but its qualification pace provided plenty of encouragement for 0002’s second trip to the Circuit de la Sarthe on 16 June.

Bob Wollek, Alessandro Nannini, and Australian Lucio Cesario took up driving duties for the 1985 24 Hours of Le Mans, qualifying a strong 3rd behind Lancia’s perennial rivals, the Rothmans-Porsches. With Wollek at the wheel, 0002 led the race for the opening three laps before deliberately slowing to cross the line in 5th position on the fourth lap, the team’s sights set firmly on conserving fuel. The car ran well until a wayward stone bounced out of the darkness and cracked the wastegate relief pipe, spoiling the Lancia’s performance and, in the words of Cesare Fiorio: “giving us the power of a qualifier in Indianapolis.” Replacing the turbocharger cost the team 30 minutes, along with any real hope of challenging for honors. Despite the problems, the Lancia battled on to finish in 6th position ahead of its sister car. The spoils went not to the factory Porsches but the Newman-Joest entry of Klaus Ludwig, Paolo Barilla, and John Winter—Ludwig becoming only the second driver since Woolf Barnato to win the race in consecutive years in the same car.

With Le Mans firmly in the rear-view mirror, 0002 completed the “back nine” of the season with the 1000 Kilometres of Hockenheim on 14 July—where it ran out of fuel and failed to make the distance—and the 1000 Kilometres of Spa on 1 September, where it took an impressive pole position before finishing just outside the podium places. The 4th-place finish at Spa-Francorchamps would mark the end of the storied racer’s competitive career—one that included two outings at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, a spectacular victory at Imola, and podium finishes at Mugello and Kyalami.

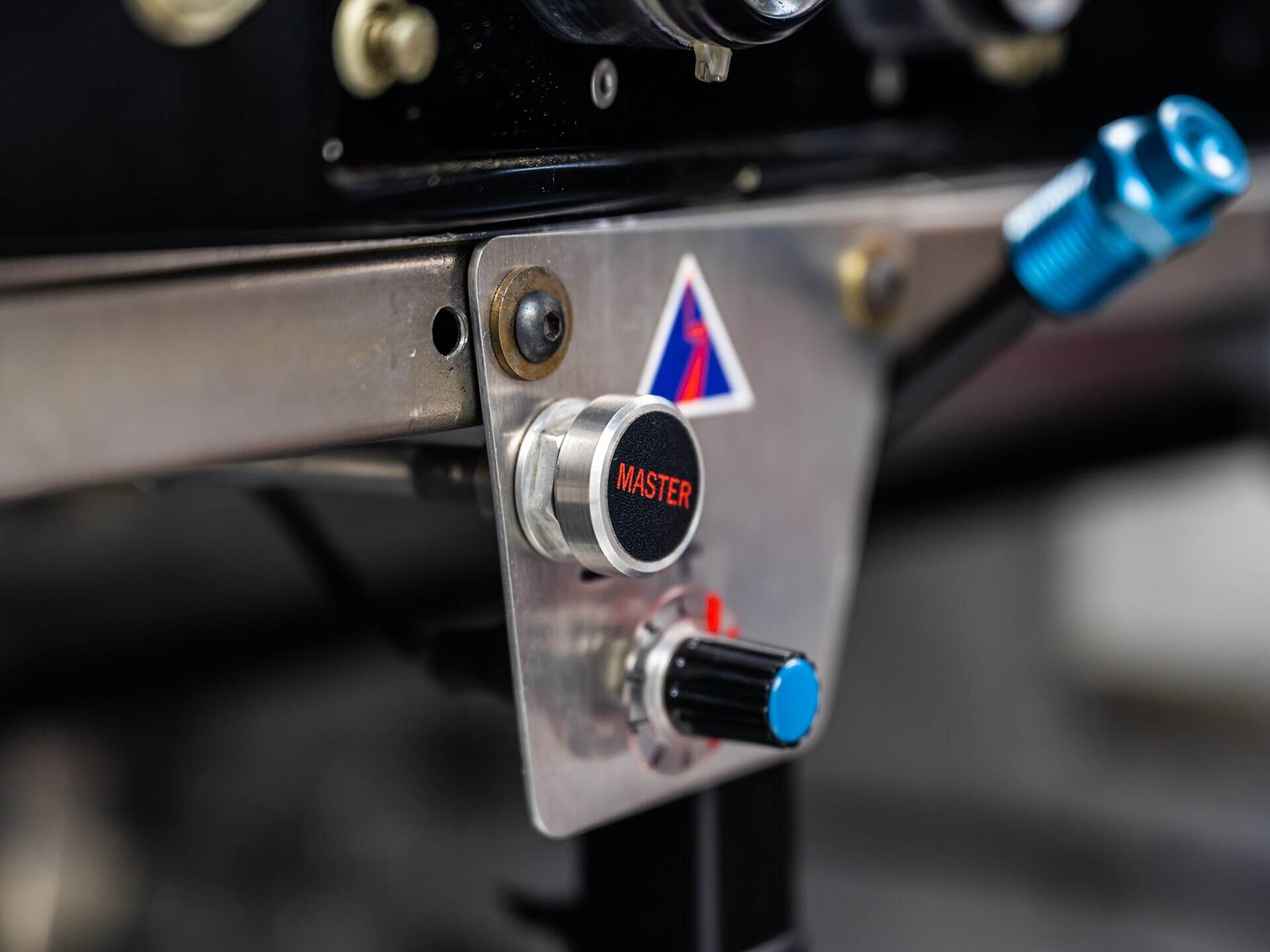

Chassis 0002 was retained by the factory for three years before entering private hands in 1988, remaining with Greenwich, Connecticut-based collector Richard Heffering until his passing in 2011. From 2012 until 2015, the car was in the care of noted collector and historic racer Roger Wills, in whose tenure the Lancia featured in a support race for the 2012 24 Hours of Le Mans, setting the fastest lap in the face of fierce competition from a much later Sauber-Mercedes. In 2015, the Lancia was acquired by the current owner, who commissioned a complete ground-up restoration between 2015 and 2016 that was entrusted to the glorious workshops of Canepa in Scotts Valley, California. Fully prepared for a new life on the historic racing or concours circuit, the work—which comprised an extensive overhaul of the engine, gearbox, and suspension—took more than 1,000 man-hours to complete and cost in excess of $320,000. The rebuild was documented in detailed restoration binders that accompany the sale, with invoices also available to view on file. Following completion of the restoration, this LC2 was Lancia Classiche certified and comes with a Lancia Classiche binder and Certificate of Origin, in addition to several periodicals, and a raft of spares ranging from suspension to engine and gearbox components, along with sundry service items. Now running with MoTeC engine management, the Lancia has yet to make its competitive post-restoration debut and has only been run selectively at private track events.

Fearsomely quick, achingly pretty, and vanishingly rare, this Lancia LC2 is not only one of the most characterful and memorable machines of the legendary Group C era—it is also the most prolific and successful example of its type in existence. Beautifully presented and exceptionally capable, this special Martini-liveried Works racer awaits only its next driver change.

This rare historic racer is for sale here at RM Sotheby’s.

Photos by Jeremy Cliff ©2023 Courtesy of RM Sotheby’s