Rarely has it seemed so vital to understand how markets cycle. As 2022 draws to a close, the stock market has become Pontiac Aztec ugly, with the S&P 500 losing 25 percent of its value from its January peak. Bonds, typically an island of stability, safety, and value, hit bargain basement prices as large pension funds and institutional investors sold them off to raise cash.

The collector car market, meanwhile, is riding a years-long hot streak. The Hagerty Market Rating, our bird’s-eye measure of the entire market, broke records throughout last summer and, at press time, remains near its all-time high. Following the sage wisdom of Blood, Sweat & Tears (“What goes up, must come down”), it’s only natural to ask how long that can last.

Legendary financier and investment banker J.P. Morgan said, “I made a fortune getting out too soon.” Right now, millions of Americans, some invested in the stock market, others holding on to assets like real estate, art, and collector cars, are observing the ups and downs, assessing their portfolios, and asking the same question: How do you know when “too soon” is?

The long game

In bear markets, stock investors find reassurance in the claim that the historic average annual return in stocks is between 8 to 10 percent. Over the long term, the trend indeed is up. But many investors fail to internalize what “long term” really means.

“I’m talking years—no one can predict precisely where they will be at any given point in the future,” said Sam Ro, a CFA and the editor of the long-term investor newsletter TKer.co. “Markets do not move in predictable ways,” he added. “If they did, then I’d be a lot richer.”

The same principles of patience hold in the car market. Over the long haul, most classics grow steadily in value. The average appreciation for vehicles that have been in the Hagerty Price Guide since 2007 is 219 percent.

Year to year and vehicle to vehicle, though, the outcomes differ dramatically. For instance, auction data show that cars purchased and then “flipped” within less than two and a half years stand less than a 50 percent chance of turning a profit. A sheer gamble, in other words. Hold out longer, and your chances improve dramatically—by year seven, auction sellers make money 95 percent of the time.

“I would say the car market is much slower moving than traditional financial markets. The swings aren’t as dramatic and severe. But it definitely has some unpredictability to it,” said David Gooding, President, and Co-Founder of Gooding & Company.

Given that unpredictability, hard-and-fast rules and get-rich-quick strategies often fail the pressure test of the real world. Take for instance, the “7 percent rule.” Very simply, the 7 percent rule is a strategy to preserve capital and cap losses, in which an investor sells a stock when it falls 7 percent or more off its purchase price. Sounds great, but David Nelson, Chief Strategist at Belpointe Wealth Management and host of “The Money Runner” podcast, notes there’s no guarantee that the next thing you invest in will do any better, especially in volatile times like ours.

“I talk to a lot of hedge fund guys that are really good asset allocators,” Nelson said, “And right about now, they don’t know where the bottom is.”

Also keep in mind that knee-jerk reactions can cheat you out of the returns you might have seen if only you’d stood pat. “Part of the deal when it comes to achieving long-run returns is understanding that you’re going to have years where the market is down 20 percent,” said Ro. Car collectors, he adds, have the benefit of being able to, you know, enjoy those investments, even in “bad” years. “Sure, the market value of classic cars, or maybe even the specific car that you own, might be falling. But unless you go in and sell, you’re not actually realizing any sort of fluctuation in the market,” Ro said.

Cars in the fast lane

Although there’s no magic number or strategy when it comes to market cycles, there are some historical patterns worth understanding. Perhaps the most important at the moment, for collectors, is the way in which tangible assets perform during tough times. In the words of a recent Credit Suisse report on collectibles, “…cars have a negative correlation with most assets, showing some counter-cyclical properties.” Translation: When stocks and bonds go down, cars go up.

Wall Street and its high net-worth clients have always hedged their traditional investments with assets like classic cars—ultra-high net worth portfolios allocate an average of 5 percent of their wealth to collectibles, according to Credit Suisse. (For comparison, the average allocation for gold is 3 percent.) Collectibles become particularly important during times of uncertainty, the report notes, as “precious stores of value…with prices based on scarcity and societal value” rather than the gyrations of the economy.

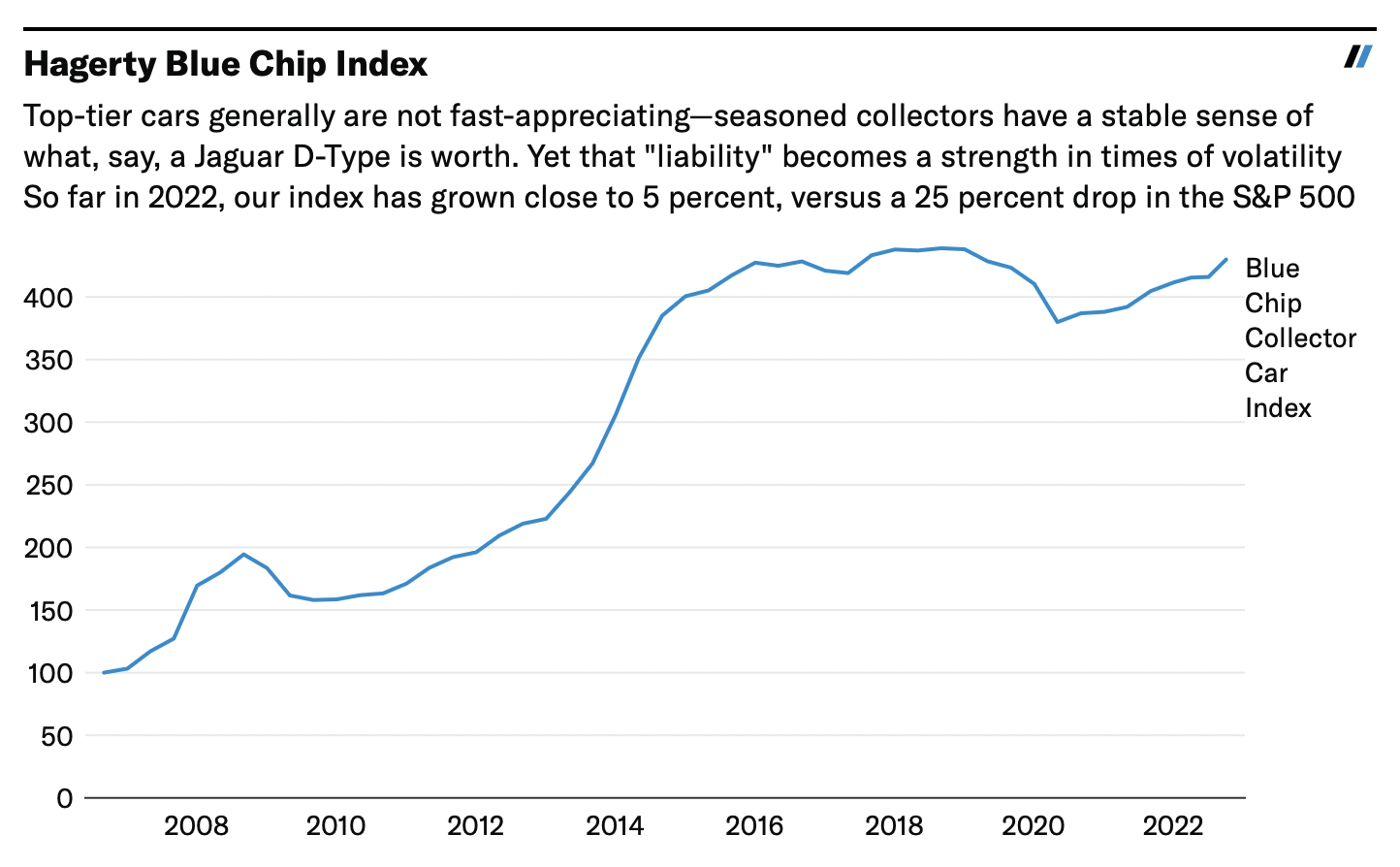

That is one reason the collector car market—particularly its higher echelons—shifted into high gear just as more traditional investments, stocks, and bonds ran out of gas over the last year. The Monterey auctions in August set a record of more than $470M, and Hagerty’s Blue Chip index, which averages the values of 25 of the most sought-after collectible automobiles of the post-war era, gained 3 percent in the third quarter of 2022.

The Hagerty “Blue Chip” Index of the Automotive A-List is a stock market style index that averages the values of 25 of the most sought-after collectible automobiles of the post-war era. Click the link to see which cars are in it.

The attractiveness of collector cars as an asset class in volatile times can become a liability, as it on occasion draws money-minded speculators who don’t sufficiently understand what they’re buying. See: Ferraris in the late 1980s and, to a lesser degree, air-cooled Porsche 911 Turbos in the 2010s.

“We certainly see people who are a bit more speculative at times, and depending on how the markets are doing, those players do come to the fore and make their presence known,” said Alain Squindo, the Chief Operating Officer at Broad Arrow Group. But, he added, we’re generally not seeing that. “By and large, it is fundamentally a passion play.”

That last observation is bolstered by UBS’s report, The Value of Collecting, which found for most people, collecting is about passion over profit. “They spend significant time and money building their collections, driven by a deep passion for their subject.” The report adds that “62 percent of collectors have never sold an object in their collection, generally because they have such strong emotional ties to it.” So much for the 7 percent rule.

The most important thing to consider when “timing” the market—any market—may be the common disclaimer SEC-regulated financiers are required to share with their clients: Historic performance is no guarantee of future performance. On Wall Street and in Las Vegas, this means the house always wins. For car collectors, it’s a license to put your passion first—because trying to play the game for the money will seldom get you anywhere.

Adam Shapiro is an award-winning financial journalist and a car nut who admits to being an awful mechanic, even though his grandfather had a junkyard in Portland, Maine. Shapiro has covered the Federal Reserve, the White House, and Capitol Hill for Yahoo Finance and FOX Business. He established the FOX Business Networks’ annual coverage of the Pebble Beach Concours in 2008.

Report by Adam Shapiro for hagerty.com