Production of the McLaren 720S, first unveiled in 2017, has come to an end. So this story about a 720S Spider might just as well have been titled “Farewell, My Lovely”, like the detective novel by Raymond Chandler. Because this is a story about goodbyes and melancholic feelings and all that. But then this Chandler guy inspired me to go in a completely different direction.

Saturday. Deepest night.

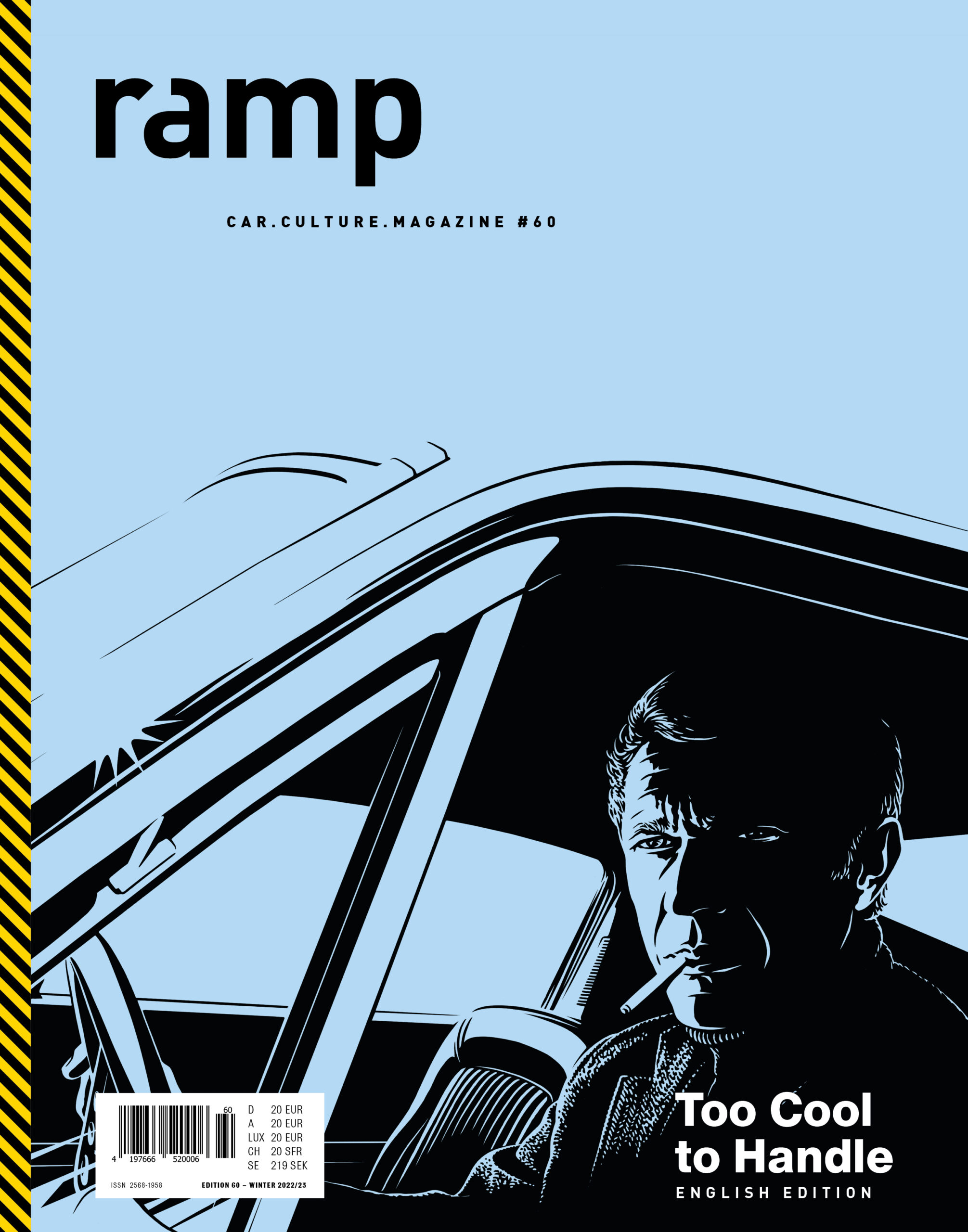

The city spread out before me with almost empty streets. A cold wind churns up the last remaining leaves on the ground. The light of passing lanterns sweeps monotonously across the windshield in an only minimally changing rhythm. Hard contrasts of light and dark, blurred shapes and pitch-black shadows underscore the intense counter-world imagery of a film noir, while the glistening fluorescent tubes of the neon signs place dazzling mask over the modern world. Feature writers and film critics love a perfect neo-noir setting. Neo-noir here being the technical term for the much freer manifestation of the genre-defining visual and narrative elements of the classic film noir transported into the present day. Fits. A cinematic experience. With me in the middle of it all. And with a McLaren 720S Spider as the ticket for tonight’s late showing.

A typical element of film noir is the urban setting. Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Chicago. Though Nuremberg, thrown in on the spur of the moment here, isn’t all that bad either. The night and its lights put things into perspective. So much for the present location.

Few other movements in cinematic history have had such a lasting impact on pop culture as film noir, a cultural phenomenon that inevitably implies style and mood, but above all internalizes a particular view of the world – pessimistic, cynical, nihilistic, dark. The translation from the French unmistakably tells us what to expect: a “black film”. The term film noir was coined in the 1940s by French film critic Nino Frank, who was one of the first to recognize this new, dark trend in Hollywood crime dramas and, together with his colleagues, immediately hailed the genre as nothing short of remarkable. There’s the archetype of the cigarette-smoking private detective, most perfectly embodied by Philip Marlowe, always with a trench coat, tough, incorruptible – but also sentimental. With a seductive femme fatale as his counterpart. The film noir themes continue to inform cinema to this day.

The first major film noir, The Maltese Falcon (1941), opened the classic era of the genre that was to dominate the iconography of American cinema for more than twenty years. Most film critics agree that the era ended with Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil (1958) – though Robert Aldrich’s radical neo-noir trailblazer Kiss Me Deadly had already drawn the dividing line back in 1955. Aldrich employed all the usual ingredients of film noir, both in form and in content, but already the opening credits, rolling down in reverse, indicate that something unusual was happening here. Aldrich’s movie uses the familiar as a cloak to cunningly and unexpectedly distort established patterns into the absurd and exaggerate them to the extreme. The death of the original film noir that is celebrated here offers a clear path for its evolutionary continuation. From now on, it’s neo-noir.

The visual form of the genre adopts a sinister, melancholic mood, with lighting as an effective storytelling tool and an expressive use of light as a means of dramaturgical expression. Realistically lit scenes and brightly illuminated faces take a back seat in noir. Uniform lighting is avoided at all costs. Scenes that are intended to build mood, main plot points and dramatic events in particular take place at night and in darkened scenery. Light and shadow not only contribute to the aesthetics of the film, they open up further narrative levels and in a variety of ways become visual metaphors. Everything is coherently adapted to the characters and to the stories of the protagonists on the cold outer fringes of society: seductive women and disillusioned men, antiheroes all of them, alienated, without a future, embittered, always taciturn and tight-lipped.

A characteristic feature of film noir is its portrayal of people who are trapped, caught in a web of obsessions, fear and paranoia, uncertain or unable to distinguish guilt from innocence, real identity from pretense. Evil is at times presented as charismatic and attractive. In neo-noir, the previous formulaic nature of the genre implodes, and the entrenched black-and-white boundaries of standard Hollywood moralisms suddenly dissolves into a misty gray, using all shades that lie in between. Crime, lust and infamy find their way via morally dubious on-screen heroes from the already depraved underworld into the seemingly so immaculate bourgeoisie. Vice is placed in the spotlight, law and order in jeopardy – and a detective of moral courage and decency is nowhere in sight. Not only were American audiences shocked; the world of cinema was changed forever.

Which brings us back to me. Me and this McLaren on this night with open roads all around. No valiant detectives far and wide who will switch on their flashing lights to fight for law and order. With 710 hp and 770 Nm at a weight of barely more than 1,300 kilograms, the spec sheet for the four-liter V8 mid-engine super sports test car promises zero to 100 in a very matter-of-fact 2.9 seconds and a top speed of 341 km/h. The perfection of sweet madness. The driver as the perfect choice to play the morally not quite solid protagonist at this moment in time. I don’t even want to think about what my colleagues, who have merrily raced this beast through the streets all these years, have had to say about this car with their eyes shining in delight. The maximum speed allowed here is 50 km/h – if ever the light in front of me decides to turn green. So this is what it feels like to be cut off from reality, I think. The dangerous is charismatic and enticing, my various selves are torn back and forth, anything but perfect. Wanton and base, I’m ready to go wild at a moment’s notice. Immediately I understand why film noir is such a pessimistic genre. In the typical film noir story, the characters find themselves caught in unforeseen situations, locked in a struggle against their own fate, with the outcome usually a grim one. At this moment, the heroes of neo-noir films are kindred spirits, my closest friends.

“Film noir is a strange bastard,” German author Paul Werner writes at the beginning of his book Film Noir und Neo-Noir. This somewhat free formulation beautifully captures the equally elusive and fascinating characteristics of film noir. The mysterious, the complex, and the phenomenon of the genre cannot really be categorically defined.

Raymond Chandler, whose novels, stories and screenplays helped shape and define film noir, also wonderfully summed up its philosophy in an essay he once wrote: “The streets were dark with something more than night,” he says, painting a picture of “a world in which gangsters can rule nations and almost rule cities. It is not a fragrant world, but it is the world you live in.”

But it’s also a world with autobahns, I think. And the next one isn’t that far away.

And while the traffic light continues to insist on red, I am reminded of the works of Finnish filmmaker Aki Kaurismäki. His dramas explicitly justify the term neo-noir. Much of his work revolves around the themes of melancholy and reconciliation. And it is precisely at this point, when Kaurismäki’s characters believe that they have lost everything, that fate always has a twist in store for them. It is precisely this twist and simultaneous turn towards fate that sets Kaurismäki’s films apart.

And then the light finally turns green.

In the end, evil in the film noir genre is usually exposed for what it is, but whether good has truly triumphed or not remains unclear and ambiguous. I briefly remind myself of this, before turning right two intersections later.

Headed straight for the autobahn.

Text: Michael Köckritz

Photos: Matthias Mederer · ramp.pictures

ramp #60 – Too Cool to Handle

As a high-impact multimedia brand that takes an all-encompassing, end-to-end approach to publishing, ramp is an absolutely authentic expression of quality, integrity and excellence. Its trailblazing luxury magazines, recognized with numerous awards over the past 15 years, have been celebrated for their cool and unconventional, not to mention inspiring and pioneering style, since day one.

ramp, the lavish and beautifully designed coffee table magazine, celebrates the enthusiasm for cars and driving in a passionately subjective, personalized fashion.

Immediate, authentic, intense. Fresh perspectives, avant-garde

A magazine about coolness? Among other things. But one thing at a time. First of all, it’s off to the movies. There’s this businessman from Boston who helps relieve a bank of a substantial amount of money. The insurance companies are on to him, but they can’t prove a thing. That, in a nutshell, is the plot of the film classic in which Steve McQueen plays Thomas Crown, who remains a mystery to the viewer throughout the entire film and who the actor plays with incredible composure, exuding absolute coolness at every moment. The German title of the film – Thomas Crown ist nicht zu fassen – hides a wonderful play on words, by the way. It could mean: Thomas Crown is unbelievable. Or it could mean: Thomas Crown cannot be caught. Cannot be seized. Cannot be grasped hold of. He’s just too cool to handle. Much in the same way, coolness also eludes our attempts to grasp it. A fundamental vagueness shrouds this fascinating phenomenon of longing and desire.

We’re fascinated by the irrational, the incomprehensible, the unbelievable. That’s why we also enjoy breaking the rules. We are living contradictions, as neuroscientists and psychologists so dryly explain. Our irrationality, innovation research tells us, is the secret to our creativity. It is our irrationality which insists that it is not we who must adapt to the world, but that it is the world that must adapt to us. This is another reason why any kind of progress depends to a large extent on our irrationality.

“If people never did silly things, nothing intelligent would ever get done,” the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once so aptly said. The physicist Richard Feynman opens our eyes to another aspect in this regard: “Physics is like sex,” he explains. “Sure, it may give some practical results, but that’s not why we do it.” And that’s just about how it was with this issue of ramp. Sort of.

With this in mind, enjoy!

Text & Photos: Marko Knab · ramp.pictures