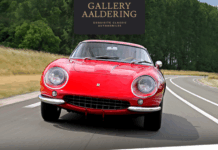

Now and then forgotten treasures emerge – like this one-off 356 1500 Pre-A Cabriolet, with an aluminium body made by Reutter.

You need a lot of imagination to guess at the uniqueness of the 1500 Cabriolet that’s driving past – even if you’re aware that only 394 such models were built by Porsche in 1953. The reason this particular car is special is concealed under the ivory-coloured original paintwork: it has a body made of aluminium. Built by Karosseriewerke Reutter 66 years ago, it’s an unusual discovery. After all, aluminium bodies have been traditionally used to make vehicles – or, at least, coupés – lighter and more agile, largely so that they can win motor races. But a cabriolet?

Quality came before speed here – that was also one of the reasons the restoration ended up taking six years.

But back to the question: “Why an aluminium cabriolet?”. Since intensive research in the archives of Porsche and Reutter does not really provide an answer, all that is left is to speculate. One possibility is that a member of the Association of Mechanical Engineers (VdM), founded in Cologne in 1892, ordered the car in this configuration, perhaps wanting to investigate whether small-scale aluminium production might be worthwhile. However, this theory can no longer be verified.

If that was what happened, surely a look back into the still young history of Porsche would have been sufficient to show the associated difficulties they might face if they proceeded: after the first vehicles were made of aluminium in Gmünd, production moved to Zuffenhausen where the decision was made to build steel sheet bodies because they were lighter, cheaper and easier to make.

The unhappy fate of the 15 aluminium-bodied 356 America Roadster cars built in 1952 (plus one Roadster with steel body) did not really promote the use of the material either. In this case the high production costs of this precursor of the Speedster resulted in the company responsible – Gläser-Karosserie GmbH – having to file for bankruptcy. Ferry Porsche later wrote in his memoirs that Reutter was not keen on welding aluminium bodies, suggesting that there were discussions on the subject but no orders. Apart from this cabriolet – which does not appear to be an order placed by Porsche with Reutter.

The car was delivered to the well-known Porsche dealer Glöckler, in Frankfurt in July 1952, but little is known about its early history. Its trail can only be picked up again only in the UK in the 1970s, when it was offered in Gloucester for a price of £1,000. “Historic and unique Porsche Cabriolet Type 356,” read the advert. “Aluminium body specially built to single order by Reutter, Zuffenhausen, March, 1953, unmarked white paintwork, new grey interior trimming, new red upholstery and new black hood, all to original standards.”

Restoration as a condition

At some point the car made its way to Germany, where its current owner was allowed to purchase it on the condition that he would one day restore it and not just put it to one side as a speculative investment. The buyer kept the gentleman’s agreement and six years ago a team was put together to ensure that the complex restoration work was carried out as perfectly as possible.

The task of coordinating the various trades was, unsurprisingly, given to engineer Rolf Sprenger who doesn’t just know all there is to know about old vehicles, but also has the right contacts at the right companies. And all of them prepared to tackle the most complex of tasks. One thing was clear: “Quality always came before speed” and this led to thousands of working hours over a six-year period.

Astonishingly, the cabriolet was used as a daily driver for many years, suffering greatly due to the ravages of time. “After an initial stock-take, it was clear that this unique vehicle had to be completely dismantled,” remembers Sprenger, “and although the car was complete, we naturally had to overhaul every part and check that it was working properly.” It goes without saying that questions and problems arose during the team’s research. How could contact corrosion be avoided? Why did the fittings on the seats not function as they should? And, not least: “How can we keep as much of the old substance as possible and restore the vehicle to its original condition again?”.

These questions that were dealt with step-by-step – leading to a remarkable result and a unique piece of Porsche history which demonstrates how keen the company was to explore new methods and meet special wishes, even from an early stage. This special vehicle also tells the story of an enthusiast, who recognised a true gem, many years ago.

Report by Porsche.com (first published by newsroom.porsche.com)