Which car and which brand of car you find cool is, of course, a highly personal matter. But when it comes to classifying a car brand as cool based on a specific set of predefined characteristics, Porsche has been leading the way for years. People all over the world see a Porsche as unrivaled in terms of coolness. And it’s probably the design that seals the deal. We wanted to know why that is the case. And who better to ask than Michael Mauer, the chief designer himself. In the end, our little talk was about a lot more than just cars.

As Porsche’s head of design, would you say you have a cool job?

I haven’t really thought about it like that. The job involves a whole bunch of different challenges that usually leave little time to ponder such questions. But I suppose I’ve always thought that being a designer was pretty cool. That goes back to the time when I didn’t yet know what I wanted to be when I grew up. My father sat down with me, and we thought about what I could do. And design very quickly became one of my favorites.

What other options were there? Michael Mauer, professional mountain biker? Or something with skiing perhaps?

I’d rather not speculate as to what my father would have thought about mountain biking as a profession. As for skiing . . . ski instructor, maybe. I guess I could still do that. But then I should get started soon. Will the interview take long?

We still have one or two questions.

For example?

How cool is the 911?

There is nothing cooler! And obviously I’m not saying that because I’m the chief designer, as the original 911 came long before my time. I’m saying it because of its cultural significance. The 911 has achieved something that is unique. It combines creative rebellion, status and authenticity. That makes it an icon. It has left its mark on several subcultural currents. At the same time, it has always been endowed with German precision and a level of technical functionality that, measured against the standards of its respective era, was always ten or fifteen years ahead of its time and always satisfied even the most demanding racing drivers. The huge fan community out there, with guys like Magnus Walker as an urban outlaw in an old 911, certainly testifies to the car’s popularity. We’re talking about car nuts in the most positive sense of the word: they know how to tinker, they know how to drive – and they know the car inside and out. These people choose a 911 because it simply looks fantastic and functions superbly. This timeless validity of design and quality is what makes the 911 so unique. I don’t know of any other car that can combine these criteria over such a long period of time and whose story is told so consistently. By the way: Whenever a meeting starts to get a bit tedious, many designers, even at other manufacturers, are always sketching 911s on their notepads. That’s probably one of the best-kept secrets of designers around the world. [laughs]

Now that you’ve told us, don’t you have to worry about never being able to find another job in the industry?

Good question. But we’re talking about coolness here, so I’ll just say: I don’t care.

Where do you think the 911’s coolness comes from in particular? What about the Porsche brand in general?

A Porsche stands out for its reduced design, a design that gets down to the essentials, to the very essence of things. And that has been part of the Porsche DNA ever since Ferry Porsche made his first car. The 356 was built and developed with limited financial resources; it was smaller, more agile, lighter, but also faster than larger, more powerful cars, which it could drive circles around. You can find a lot of the brand’s coolness by going back to its roots. The pure, nimble, small, likeably unpretentious sports car appealed to individualists, above all to people who wanted something from life, who wanted to shape life according to their own ideas and dreams. Restless spirits, adventurers, go-getters, artists. And among them many women. That’s where themes like rebellion and self-confidence come from. And it’s still like that today.

Can you give us a better idea of what that means?

Internally, especially with the sales and marketing people, we often talk about the valence, or hedonic value, of a Porsche. That means: When I get in my 911 Turbo and park it downtown next to a Ferrari or Lamborghini, the hedonic value, i.e., that part of the car that visually screams, “Here I am, a powerful car,” is relatively low, not to say modest. But the thing is, with the Turbo you can easily keep up with most of the cars that have a high hedonic value. You can even outdrive some of them without really noticing it.

An easy-going, laid-back understatement, in other words. Knowing what constitutes one’s own identity . . .

. . . but not having to constantly talk about it every chance you get. I think that’s what defines coolness in general, and that’s also what makes a Porsche cool. It’s a natural sort of nonchalance. That’s also something you see very clearly in the design. When I look at a Porsche, it absolutely stands out for its proportions and for its clear and – quote, unquote – simple surfaces. Nicely curved, as if to say, “I don’t have to prove how fast I can go from zero to a hundred. But when it comes down to it, gladly. Anytime.”

Can design be cool in its own right?

Hmm . . . that’s a tough one. We’re basically talking about two things: luxury products and coolness. Both can only be perceived through their interaction with the world around them. Coolness as a kind of intentional demarcation from everything uncool within a subculture. A brand’s product is ultimately the necessary ornament of this demarcation. With this product, the cool person distinguishes himself from the uncool. Seen in this way, the product itself cannot be cool at all; when a person chooses a product for cool demarcation, they make it a product for cool people. I suppose this also makes the design cool in some way.

So it’s more the act of doing something that appears to be cool?

Definitely. I was sitting in the car the other day stuck in traffic. There was this guy in the car next to me with a cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth. He probably thought he looked cool. I didn’t think so. On the other hand, if the government were to ban smoking completely, smoking might be considered cool again.

Can luxury be cool?

In this respect, I agree with the philosopher Lambert Wiesing when he says that one aspect of luxury is always the self-determined deviation from norms and ideas of convention. It’s always about one’s own attitude to things, combined with a very personal experience. As in art, the breaking of rules, the rejection of conventions, is seen positively. That’s why not living up to established norms can be perceived as a beautiful and individual statement of luxury. Let’s take an example that many people immediately associate with luxury: a marina in the south of France. And then someone comes along with their five-hundred-million-euro yacht. Do I think, “Wow, cool”? Or do I think, “Oh no, please don’t”? If, on the other hand, the guy is a famous multi-billionaire and he comes rowing in with his own rowboat, I immediately think: cool guy!

Clearly, what makes a brand cool is difficult to put into words. On the other hand, it is extremely important for brands to be perceived as cool. These days, designers have come to play a much greater role as brand creators than was the case twenty years ago. How do you make sure that Porsche is seen as a cool brand and that it remains cool?

The best way is probably not to think too much about whether the brand will be perceived as cool in the future or not, but to simply keep addressing the tangible aspects of the Porsche identity in a purposeful way. Intentional coolness won’t work. It’s better to focus on what has already had a lasting impact on the brand essence, based on the established image. That would be things like authenticity, which is easily defined by our claim to ingenuity and functionality, the original, instantly recognizable, typically clear, pure design language, and the connection to a very characteristic, unmistakable user experience. That begins with the little things, such as the fact that the ignition in a Porsche is situated to the left of the steering wheel and not to the right. Of course, it also includes the design of the overall interior, the position of the driver at the wheel, the ergonomics of the seats and the steering wheel; in other words, all the factors that have a significant influence on the driving experience. Moving on to the exterior, a Porsche is always about proportions, aerodynamics and design, as well as the interactions between these individual factors, which can be highly complex.

So it’s also about recognition?

Of course, recognition is essential. Though Porsche has also broken with design tradition before. That, too, is an aspect of coolness. Just think of the 924 or the 928. For me, the 928 in particular was and is an example of a breathtaking design that was bold, but probably too far ahead of its time. With the Boxster, Porsche opted for a design that was more like the 911’s in order to clearly illustrate the kinship for buyers. This is also the origin of the two cornerstones on which every Porsche product stands today: brand and product identity. Brand identity ensures that I recognize a Porsche at first glance. Product identity ensures that I recognize which Porsche it is.

How do you make sure the work remains systematic and grounded? You’ve defined a set of Porsche design criteria. What do you need something like that for?

It’s important to have some basic principles. That way, you’re always on the safe side. But these principles should be understood as only giving you a rough sense of direction. They always have to be, shall I say, updateable. I have to be able to adapt my principles. If you’re looking for an archetype that defines the identity of the Porsche brand in terms of coolness, I’d say it’s the rebel and adventurer. A rebel or an adventurer is a great representative of coolness. So at least that gives you a certain image, and most people love clear and unambiguous images. Archetypes serve as part of a navigation system, if you will, for a creative free space. Basically, I am a proponent of the compass approach: roughly indicating the direction you want to go, defining a central theme, laying down principles. This also makes it easier for the designer to react more quickly. You need to know what the essence is about – and then you work on that essence. This is good for autonomy and authenticity. We’ve been working with this principle in design at Porsche for years, and I think it serves us very well. After all, the job of a good designer doesn’t end with just delivering a beautiful product; it’s much more about having a continuous and consistent design, a coherent, end-to-end brand experience. I can’t remember who it was, but someone once said that as designers we have to let the superficial work its way into our subconscious.

An interesting thought.

I couldn’t have said it better myself. [laughs]

Courage is an essential component of coolness, isn’t it? How willing to take risks must you be as a designer?

I think we need to stay provocative at all times and constantly put alternatives up for debate, which is why I say: Of course, we have to be courageous. But the real question is: How far do we go? And what is my relationship with my superiors? Still, courage is a basic necessity.

How do you determine whether you’ve gone far enough – or perhaps even too far – in your decisions?

By gauging the reaction of our own people when we introduce a new model, for example, and they tell you that what you’ve designed is no longer a Porsche. Then you know you’ve gone a bit farther than someone outside of the design department can understand. But if you’re convinced of your idea, then it’s still worth fighting for it. You always have to keep in mind that these people, the ones who see and judge the new model at that moment, often expect only small evolutionary steps, but that we like to push things a bit further in order to make greater changes more quickly.

Do you encourage your designers to come up with bold or perhaps even rebellious solutions?

You’d probably have to ask them that yourself. I usually tell people to push things a bit further when I feel it is right to do so. But I always say that there should be no limits at the beginning of a project. On the other hand, I’m also the person who comes along and says, “I don’t like this, this is going too far. . .” So I’m the guy who encourages people to try something new, but also the one who puts on the brakes when needed.

So is design cool if it is bold?

Not necessarily, although coolness is also in the eye of the beholder. Bold, that’s always the fine line between “different for the sake of being different” and “different for the sake of being better”. But what is better? There are often designs that were done very boldly, but which weren’t successful in the market. These designs may have been bold, but they obviously weren’t cool.

And what is bold design?

A good indicator is when someone doesn’t immediately resist a new design, but says, “Wow, now that was really unexpected!” That shows me that we’ve gone a little further than anyone would have expected. And that is exactly where the difficulty lies, because sometimes you just go too far. It’s quite the same in our everyday lives. I ski a lot, even off-piste, and that certainly takes a certain amount of courage. But if you’re too daring, it can cost you your life. Assessing a situation correctly is often a matter of gut feeling.

Is there a fine line between courageous and overconfident?

I think there is. I also think the more experience and the more skill you have, the better you can trust your instinct. The younger and more inexperienced someone is, the more they will probably let themselves be spurred on by adrenaline and will tend to push the limits into the realm of overconfidence. That reminds me of this video of a snowboarder I saw the other day. He’s coming down this beautiful incline off-piste, triggers a huge avalanche, rides ahead of the masses of snow, comes to a rock overhang, does another backwards flip, lands, rides along in front of the avalanche again, and makes it out. At first, I thought, “Wow, how cool is that?” But after a couple of minutes, I just thought, “Actually, the guy’s an idiot. Because if anything goes wrong, he’s dead.”

So do the limits invariably shift down the more experience we have?

I wouldn’t say that. The limits can certainly shift up as well. With experience, I can assess risks much better. The older I get, the more courageous I can be, because I have the experience and the knowledge about what the best way to do something is, what the right step is, without taking an insane amount of risk. Experience can also teach you at what point you have to say: this far and no further.

Interview: Michael Köckritz

ramp #60 – Too Cool to Handle

As a high-impact multimedia brand that takes an all-encompassing, end-to-end approach to publishing, ramp is an absolutely authentic expression of quality, integrity and excellence. Its trailblazing luxury magazines, recognized with numerous awards over the past 15 years, have been celebrated for their cool and unconventional, not to mention inspiring and pioneering style, since day one.

ramp, the lavish and beautifully designed coffee table magazine, celebrates the enthusiasm for cars and driving in a passionately subjective, personalized fashion.

Immediate, authentic, intense. Fresh perspectives, avant-garde

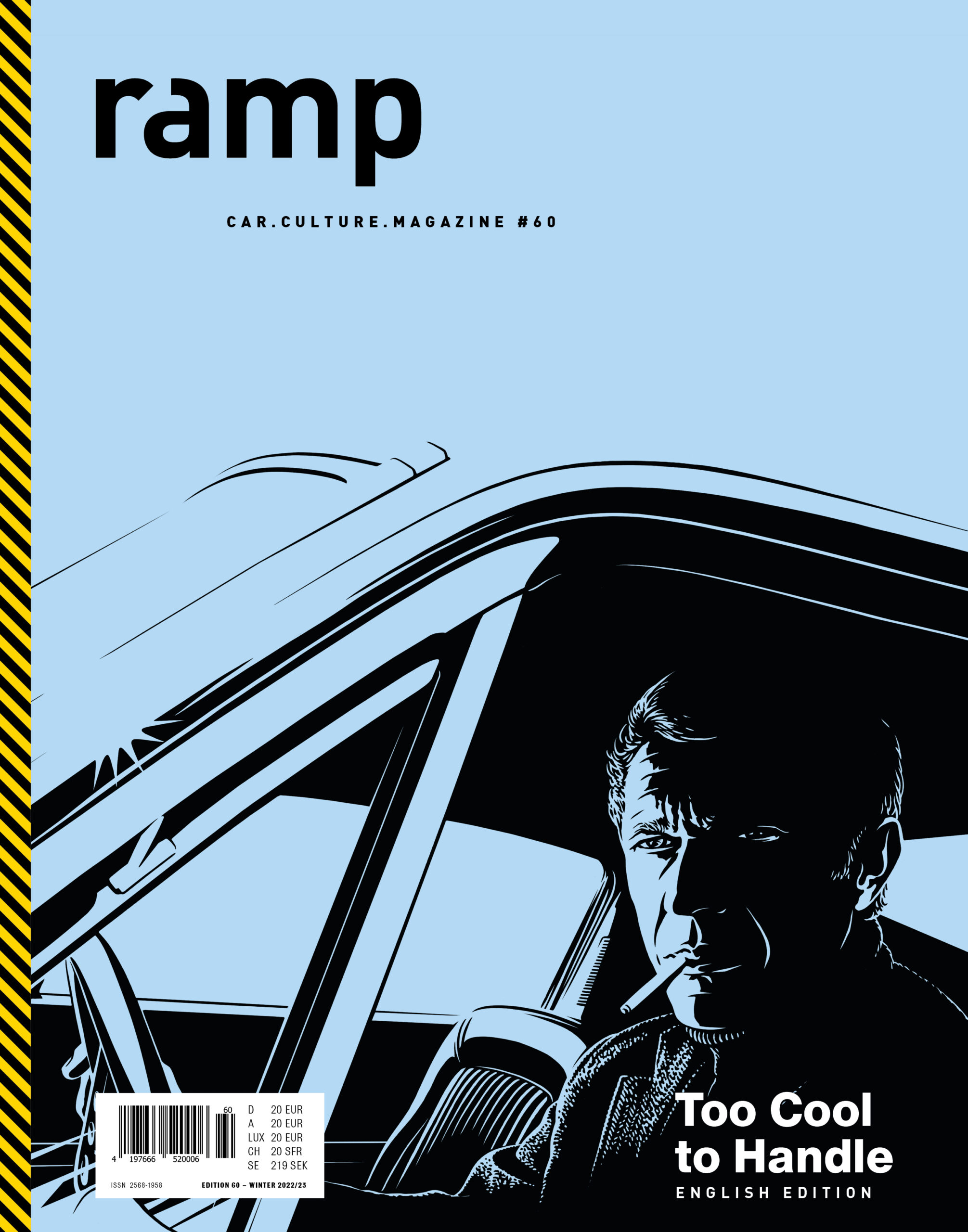

A magazine about coolness? Among other things. But one thing at a time. First of all, it’s off to the movies. There’s this businessman from Boston who helps relieve a bank of a substantial amount of money. The insurance companies are on to him, but they can’t prove a thing. That, in a nutshell, is the plot of the film classic in which Steve McQueen plays Thomas Crown, who remains a mystery to the viewer throughout the entire film and who the actor plays with incredible composure, exuding absolute coolness at every moment. The German title of the film – Thomas Crown ist nicht zu fassen – hides a wonderful play on words, by the way. It could mean: Thomas Crown is unbelievable. Or it could mean: Thomas Crown cannot be caught. Cannot be seized. Cannot be grasped hold of. He’s just too cool to handle. Much in the same way, coolness also eludes our attempts to grasp it. A fundamental vagueness shrouds this fascinating phenomenon of longing and desire.

We’re fascinated by the irrational, the incomprehensible, the unbelievable. That’s why we also enjoy breaking the rules. We are living contradictions, as neuroscientists and psychologists so dryly explain. Our irrationality, innovation research tells us, is the secret to our creativity. It is our irrationality which insists that it is not we who must adapt to the world, but that it is the world that must adapt to us. This is another reason why any kind of progress depends to a large extent on our irrationality.

“If people never did silly things, nothing intelligent would ever get done,” the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once so aptly said. The physicist Richard Feynman opens our eyes to another aspect in this regard: “Physics is like sex,” he explains. “Sure, it may give some practical results, but that’s not why we do it.” And that’s just about how it was with this issue of ramp. Sort of.

With this in mind, enjoy!

Text & Photos: Michael Köckritz · ramp.pictures