Tom Meade’s fabulous Thomassima cars were created from the diluted essence of Ferrari while including only a few vital components from that historic legacy. Their voluptuous forms followed the historic sweeps of speed in the eyes of Meade’s mentor, Menardo Fantuzzi, the automotive sculptor of Modena, as much as it did in the teardrop sculptures of Joseph Figoni in Paris. It looked to be the way high-speed air found its way around a solid object. When it looked right, it was right.

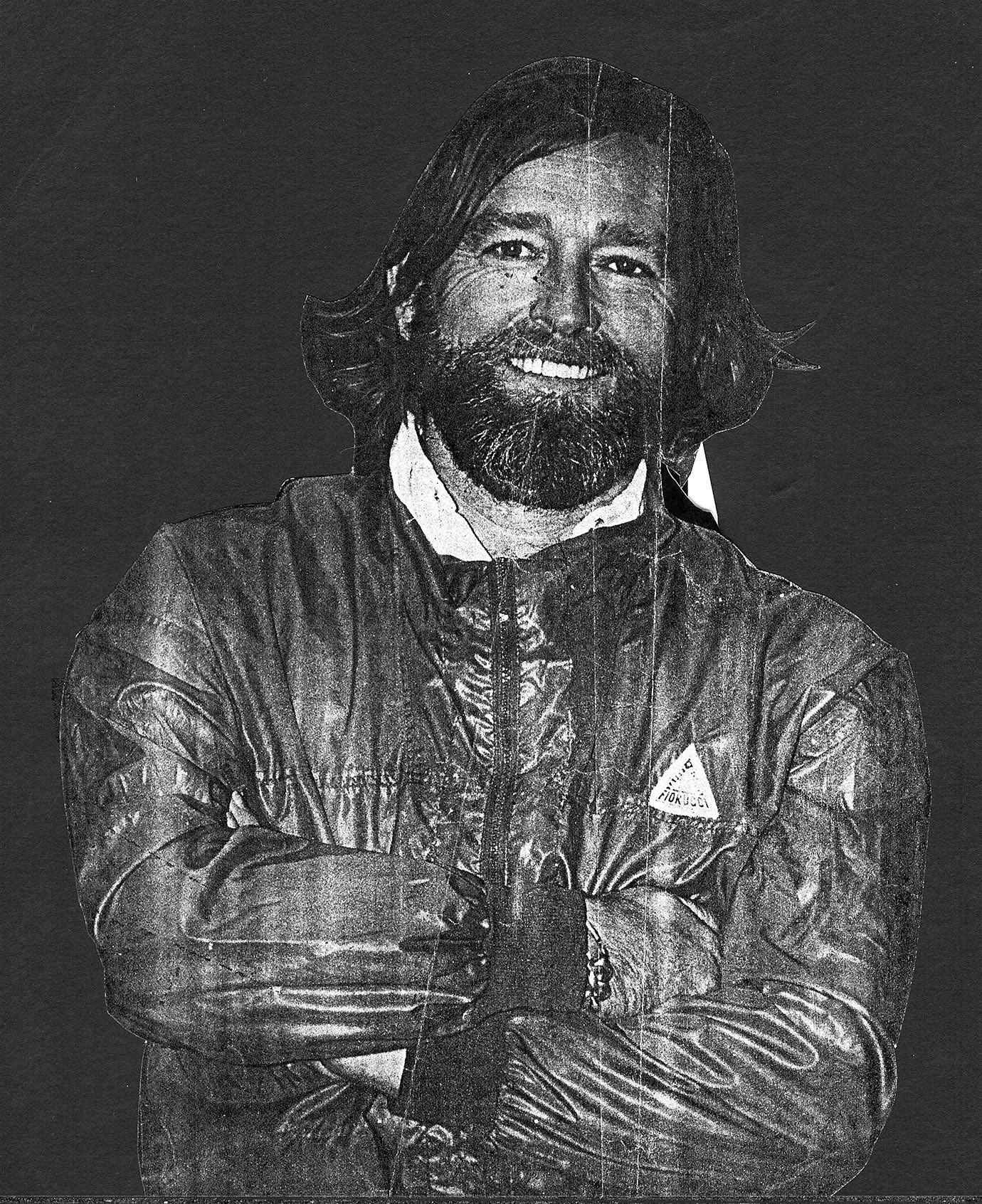

Nascent Thomas Meade was delivered into the Hollywood vortex of creativity and chaos on January 19, 1939; by the age of eight he and his mother had made their way to Australia. Tom now proudly declares he wore the first pair of Levis ever seen there. To that point every young man in Australia wore short pants. Within a couple of years they relocated in Honolulu, Hawaii, where he remembers being the only haole attending the Iolani Elementary School in the Nu’uanu Valley up on the Pali.

He did shoe shines for GIs for spending money, bought his first surfboard in 1952 and remembers spending summers living in a Banyan tree on Waikiki, surfing and making surfboards with Joey Cabell. Tom remembered his mother convincing her bright, surf-bum son they needed to head east for him to attend high school in Newport Beach, California — a successful decision. He graduated at 17 and she immediately enlisted him in the U.S. Navy for four years of adult supervision. He was trained as an aviation electronics engineer at North Island, San Diego, and traveled the world for four years by aircraft carrier, first the Oriskany (CV-34), then the old Yorktown (CV/CVA/CVS-10). In 1960, fresh from his “world tour” with the Navy, Tom thought he had seen everything. Until the Ferrari — and the story.

Only the tail was visible. It was an Italian posteriore; elegant, sensuous, and spellbinding. It was the most beautiful car Tom Meade had ever seen. He had noticed it before on his walk home from work, but this time a figure was moving in the shadows at the back of the garage. Without hesitation, he walked straight in to see what this shape belonged to. “It’s a Ferrari 500 TRC,” explained the owner, who was busily engaged under the hood. “It is only a two-liter four, but it has double overhead cams and two big Weber carbs. And it’s light and fast. You can have it for $4,000.” After the name, the rest had been lost. “Where’d you find it?” “There is a warehouse in Rome full of these old racecars and they are all for sale – cheap.” The owner offered it to him for $4000 – probably $3000 too much at the time. Any-thousand was too much for Tom. The owner mentioned the Roman warehouse and cheap in a single sentence. An epiphany. Off to Italy – and a future – in the blink of an eye. Tom Meade had a direction. He started doing research about how to get to Italy. Cheap. Work for passage on a freighter. There were no Europe-bound freighters from the west coast so the target was the east coast to find one. Just before leaving home he discovered that there were freighters leaving from New Orleans headed east across the Atlantic. “So I left Newport Beach, California, and hitchhiked, bound for the port at New Orleans with 50 bucks in my pocket,” Tom remembered, during a 2012 interview with Chad Glass in Los Angeles. “While still in California I was picked up by an Australian, a plumber. Having lived and gone to school in Australia before, he and I hit it off well and became fast friends. “We headed straight to New Orleans and got an apartment together in the French Quarter off Bourbon Street, during Mardi Gras. While staying there, there was a break in to our apartment. But it was the police who broke in – breaking down the front door without a warrant, guns drawn. It scared the hell out of us. After scaring us half to death they realized they were looking for someone else.

I had no money, no knowledge of mechanics or cars, no family, no backup, nobody to help me. And I knew no one. Italy was a foreign place and I had never been there or even to Europe. I could not speak Italian but was leaving for Italy. It was my ‘mission impossible,’ with the future ahead of me. And still it was very exciting in the midst of it all.” By the time Tom arrived in England his shipmate had already bought a Triumph motorcycle from an American tourist headed home. Transportation. The two guys rode to Valencia on the Spanish coast and sold the bike for passage to Mallorca. A hotel in Palma offered a rooftop camp site for a dollar a day. After six months of parties in multiple languages the roof-mate left for more adventures in Africa, and Tom booked a working passage on a sailboat bound for Genoa. Finally, Italy. While in residence in a hostel near the port he was offered an inoperable motorcycle left by a former guest. Tom disassembled and rebuilt the bike at a nearby gas station while learning both mechanics and Italian, then was off to Rome in search of the mythical warehouse. In a Roman inn he met a guy who was working nights on a Dino De Laurentiis film called Best of Enemies. He took Tom onto the set and De Laurentiis immediately hired him to play a background English officer, working with David Niven off and on for several months. Tom joined the film’s night crew and searched for the “the warehouse treasure” during the day — urban myth. When the film was finished, he set out for Modena, the epicenter of fabulous cars. “I slept under woodpiles in my sleeping bag when I arrived in Modena.” Tom continues, “I had no money for a hotel or pensione. But I knew one thing: I had to own a Ferrari or Maserati. With everyone saying ‘you’re a crazy man, you don’t have any money, that’s impossible, you’ll never be able to do it.’ – naysayers. That only made me more determined to succeed.” One evening a pedestrian suggested that Ferrari was 15 kilometers down the road and it was too late to go there, but Maserati was nearby. He arrived at the Maserati gate at 7:30pm and found the place closed and mostly deserted. Finally, the gate guard, impressed that an American was interested in visiting his company, called someone to come out and talk to him. That person was Aurelio Bertocchi (son of race director Guerino Bertocchi), who happened to be working late. On his personal tour Tom spotted an old racecar under a dust cover setting on sawhorses with its drive train out. He asked Bertocchi if it was for sale. “No. We don’t sell beat up old race cars to our clientele.” Maserati traditionally took last season’s racecars and dropped them in a swampy field behind the works. Wrecking yards would not take them for free, because it would be too time consuming and expensive to pay someone for disassembly to separate the various metals. Bertocchi was giving the tour assuming the young American was there to buy a new 3500 GT. Finally, the private tour returned to old racecar and Tom convinced his guide that he really wanted the old race car first. He would come back tomorrow to talk about the new car. Bertocchi called the office and asked for a price; it was the equivalent of $450. The shocked expression on Tom’s face caused Bertocchi to lower the price to $420. Tom said “Sold,” but he wanted the car that night before anyone discovered their mistake the next morning. It was 8:30pm when Bertocchi place a phone call to a friend with flat bed truck. By the time Giorgio Neri arrived at 9:00, most of the missing drive train had been gathered up to be included on the truck. Tom followed the load through Modena, staring into the face of his own Maserati. The load was deposited in the carrozzeria Neri co-owned with Luciano Bonacini and arrangements were made for Tom to put his sleeping bag on a mat next to his project. In the light of morning he realized he owned a 350S. Later he discovered that it was one of only three and his car, number 3503, had been driven in the 1957 Thousand Kilometers of Buenos Aires with the latest six-cylinder and the new in-line transaxle with deDion tube. Upon its return to the works it was modified for the 3.5-liter V-12 and was entered in the Mille Miglia for Hans Hermann but suffered a dnf. It then ran the Nürburgring 1000 km, the 500 Miles of Monza, and returned to the Nürburgring in ’58. Tom had bought it in that 1958 V-12 form. The mechanics in the Carrozzeria Neri e Bonacini shop improved Tom’s Italian while he worked to assemble his car. It was soon obvious that there was no room for a freeloader in the modest facility. Bertocchi introduced his energetic protegé to another friend with a farm who let Tom have a barn to work in and the haymow as sleeping quarters.

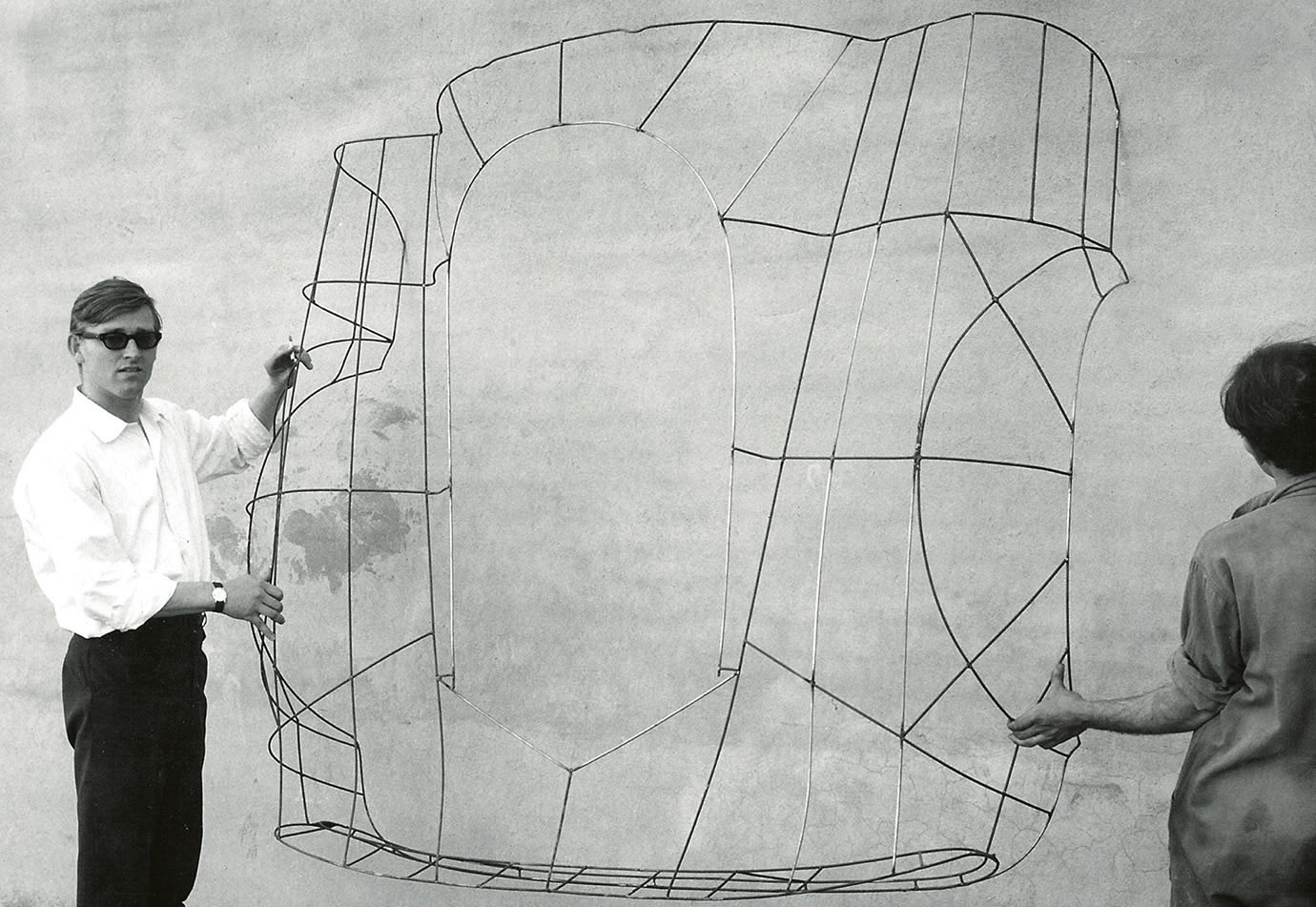

Every day he rode a bicycle to Maserati in search of necessary pieces. So, every day Bertocchi had to walk him through the factory to the storage room where simple unmarked boxes of racecar parts lined shelves at the back of the warehouse. Many boxes had to be explored to find the necessary one or two pieces for that day. Before long the young American was a regular presence and could often be found in the mountain of discarded parts they called storage outside the Maserati race shop. Eventually, he was given access to the parts warehouse and became more aware of the whereabouts of everything than anyone else in the company. Bertocchi finally commissioned Tom to furnish all the spare parts required by private teams in exchange for whatever he needed for his project. In that capacity he met fellow expat Lloyd “Lucky” Casner who was fielding a Birdcage and a GM backed Corvette with his Camoradi International team. After an event in Sweden, team mechanic, Bob Wallace, dozed off and left the road destroying one of two carefully engineered Duntov Corvettes. Casner offered the wreckage, all remaining spares and the trailer to Tom for $400 — including a very special engine. It found a new home in an equally historic Maserati as Tom Meade’s first complete roadworthy racecar. The racing mechanics became his friends. A few spent their off-hours in the barn helping Tom with his project and, not insignificantly, improving his Italian, as they tried to fathom English. The mechanical parts were coming together well, but the body which had sat outside for four years was badly deteriorated. Bertocchi introduced Tom to Medardo Fantuzzi to help restore the body. It seems the popular Italian racecar builder shared the young American’s enthusiasm for English motorcycles, so it was arranged that he would take Tom’s transportation in exchange for body work and mentorship. Though not known at the outset, the deal would soon include a “residence” as Tom moved into Fantuzzi’s shop. He slept on an iron army cot, next to the oil heater during the winter, living there for a year while Fantuzzi graciously mentored him in both metal shaping and design. On weekends he had the shop to himself and would go out for bread, salami and wine and work on the new body. Fantuzzi mentored him in the quality of craftsmanship as much as the art of coachwork. The maestro seemed to understand that the young Meade had the gift of design and was able to absorb the details of classic form and proportion as well as metal shaping and fabrication. Medardo Fantuzzi’s mentorship was Meade’s baccalaureate degree in both form and process. The manichino (wire framed maquette, or 3-dimensional study) followed a series of drawings right to the chassis of the car.

A 246 Dino rebody manichino is shown once the wire framework was carefully formed and finalized, the wire sculpture, mounted on its rolling chassis, was trucked over to Autodromo in Modena. Each of the local corrozzeria used them to form the avunal (aircraft aluminum T60 or 61) panels to fit its manichino. Those panels were finished and the complete, overlapped set were pinned to the wires and the unfinished, paneled sculpture was returned to the artisan’s studio. There the fenders, hood, roof, etc. were carefully hand cut to so the edges would butt together and fit snugly on the wire frame. When everything fit, the sections were gas welded, hammer finished and the final form refitted to the manichino before a bicycle-tube frame was constructed to support it from beneath. Bike shops were the source for high-quality chromoly 4130 steel alloy tubing. It was strong, easily worked and welded, and inexpensive in low volumes. Fantuzzi taught him as much as his young protégé was able to absorb. They even designed and constructed a removable hard top for the old racing roadster that was built around a 3500GT rear window, cut down and fitted as a windshield. Tom took the car back to the States to sell. Unfortunately, he loaned it to an old friend who promptly ran it over a cliff, destroying it. The wreck was sold for a fraction of what it might have been worth. The ever more dedicated expatriate moved back to Italy. Meade bought one of the other 350S derelicts for $80 and started over. When it was finished, he sold it too into California, and met America’s favorite Italophile, Dick Merritt, during the process. Dick said he had a customer for a 250 SWB and asked Tom if he could find one for him. Tom did, and another profit center was established. Now with an actual income, however spotty, Tom rented an apartment with a balcony a couple of blocks from the Modena Aero/Autodromo. At last, there was enough money to begin designing his own cars – his dream from the beginning. He managed to buy a number of out-of-date Ferrari and Maserati racecars for pennies on the dollar as preparation for future projects. At one point he bought a Ferrari GTO64 for $720 that became his daily parts runner. Tom eventually partnered with David Piper (a famous British Ferrari racer he had met at the autodrome) in a storage space Piper could call his team’s Italian headquarters and Tom called his design office. It was where he began creating what would become the iconic Meade Ferraris. His most effective “production” was a series of 7 or 8 Lussos fitted with GTO-like noses, not unlike the 330LMBs Mike Parks developed for the SF endurance racing team. Most of Tom’s versions were created from crashed or out-of-commission Lussos bought around Emelia Romagna for little money. One of them made its way to Anchorage, Alaska, to the ownership of Ralph Stefano, founding member of FART (Far Alaska Racing Team). There were other “custom” alterations made to a series of Ferraris. From his growing circle of Modenese friends Tom began to collect a broad assortment of racecar pieces for future projects. While these “customs” were sculptures done for pleasure, he was creaping slowly toward being in business.

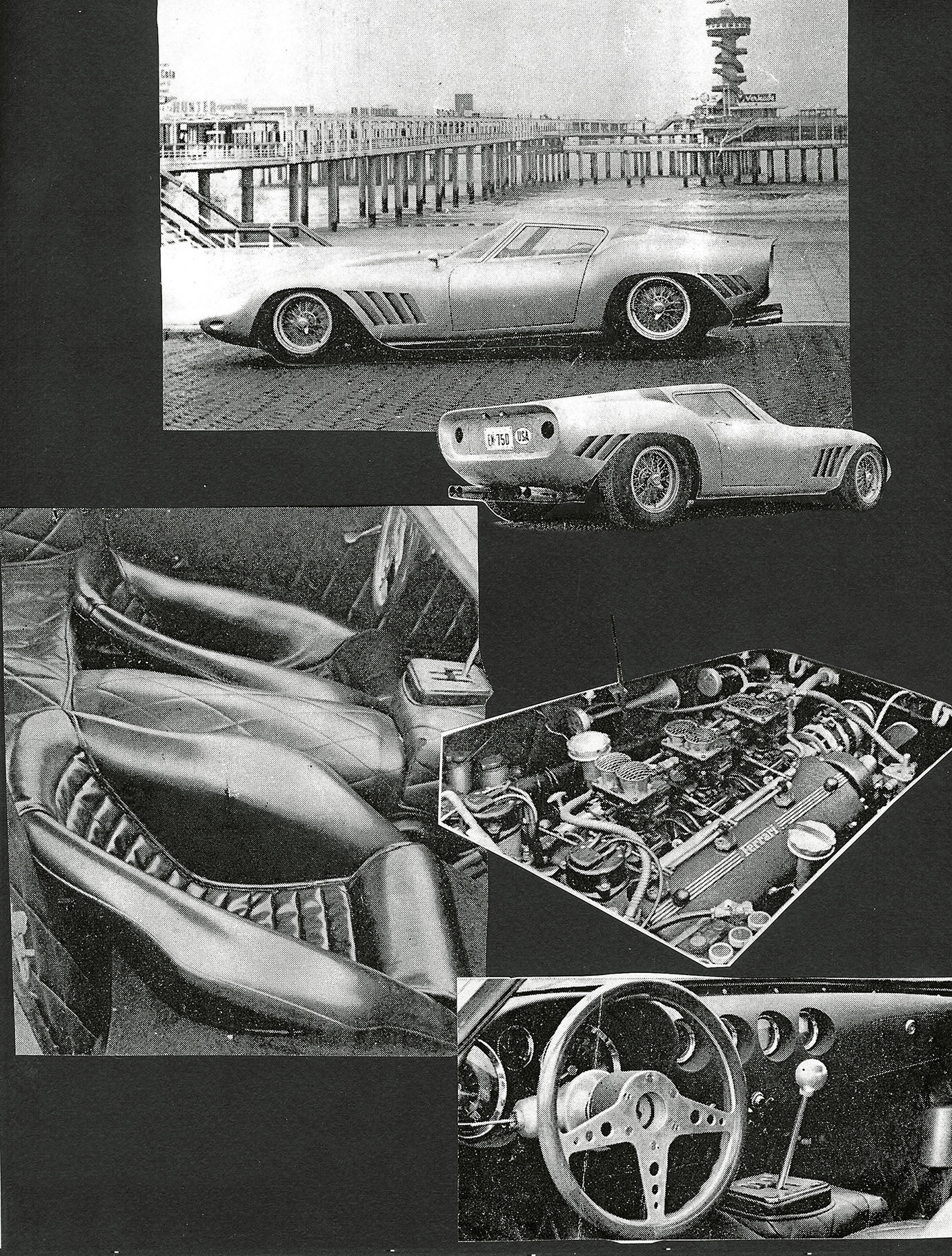

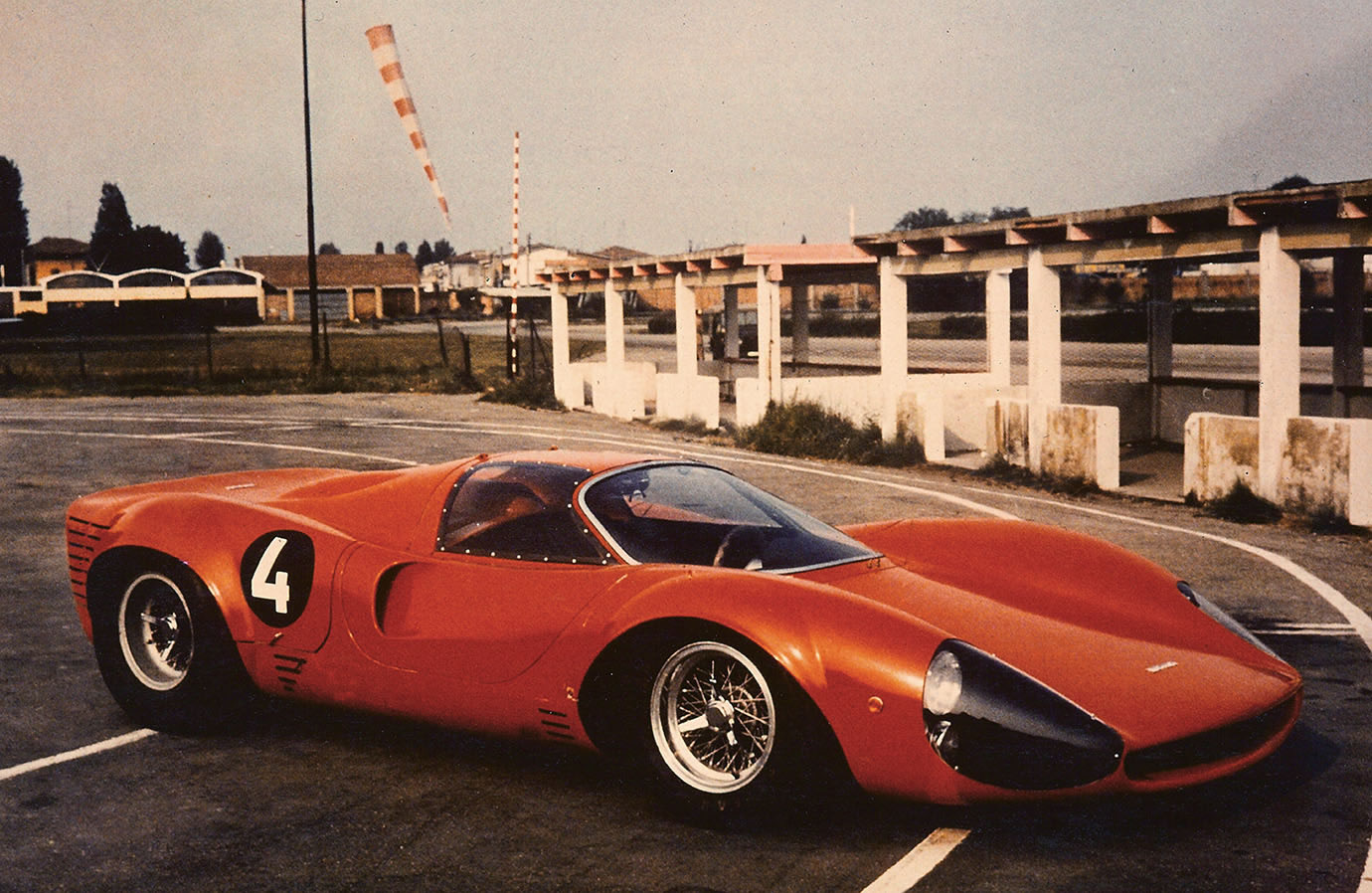

Thomassima I was Meade’s first complete car. It was based on a Ferrari 250 GT, but illustrated the profoundly personal Thomassima form so dramatically it was invited to be shown at a classic car exhibit in Florence. Once again fortune failed to smile on the young designer’s elegant forms. It was a dream coming true, but in a wet season, the Arno over-spilled its banks flooding the facility where Thomassima I was awaiting its public debut. It was irreparable, a total loss. Early in 1966 legendary Los Angeles Ferrari “importer” Edwin K. Niles made contact with the growing Ferrari legend, Tom Meade. A visit was planned to get a better perspective on his ex-pat friend. Tom joined Ed’s cadre of Italian ferrits, who extracted good cars from unusual places, repaired or replaced problems and shipped them to Ed and new lives in America. He found Tom secreted in a small apartment above a pair of garages which he had included in his living arrangement. The apartment was full of Ferrari and Maserati engines and components. In the wall of the equally packed garage hung a formula one frame Tom described as a DeTomaso. It was later discovered to be a Cooper Type 43, which might have been the one raced at Monza by Tom’s coachbuilder friend Piero Drogo in 1960, though Alejandro De Tomaso did construct a small series of F1 cars for the 1961 season based on Cooper components. Sadly, the historic spaceframe was disassembled to become both lost and legend as elements in the skeleton of Thomassima II. Tom Meade had reconstructed or customized a dozen or more cars before he met Harry Windsor of Los Gatos, California, late in 1966. His new friend commissioned Tom to create a car for him with the look of the recently announced Ferrari 330 P3. Tom expected to deliver the car in 6 months. It was not that simple. Disassembling the Cooper space frame and reassembling elements of it with new side rails and bottom frames to fit new dimensions was an untidy undertaking. Most of the finished product would not have qualified for either a Cooper, Ferrari or Maserati technical specification. Power was delivered by a early inboard-plug Ferrari 250 GT engine capable of 240 horsepower; enough for a car weighing just under 2000 pounds. Adaptor components attached it to a 4-speed ZF commercial vehicle front wheel drive unit that was inverted for its mid-engine use, just as the “Ferrari palace-coup d’état” group — including Carlo Chiti, Giotto Bizzarrini and financeer Count Giovanni Volpi — had done for their ATS GT project in 1962. Suffering the results of Tom Meade’s tunnel vision focus on his body project, the once carefully engineered formula one chassis was soon little more than a three-dimensional study for one that would support two people and a completely upholstered coupé. And it became an altogether more technically demanding project than expected. With the Cooper F1 chassis as a structual pattern, its clone was first plotted on panels of marine plywood laid on the floor of the shop. Local bicycle shops were the source for high-quality chromoly 4130 steel alloy tubing. It was light, strong, could be welded, and inexpensive in small sections. As the tubular structure became three-dimensional the artist/visionary revisited DeTomaso for the Cooper’s suspension components. Meade secured the complete set of Cooper-modified cast steel English Standard/Triumph front upright units and Cooper’s own hollow cast magnesium Formula One units for the rear. The tubular A-arms and disc brakes for all four corners were included but the Dunlop racing calipers were replaced with Girling road car units that included emergency brakes in the rear set.

At this early stage, Tom Meade was less an automobile designer than an artist; a sculptor who created wire-frame drawings to be made whole as voluptuous aluminum sheet forms by his artisan friends at Corrozzeria Sports Cars. Thomassima II’s roof form was preordained by the Alfa Romeo Sprint Special rear window which made an elegant windshield, and the removable top and sidewindows required by Windsor to offer an open roadster when the Bay Area weather permitted. The mechanisms were designed and patented by Meade. When the body was completed, it became a beautiful piece of art created over an automotive chassis that located four wheels and a driving compartment within a dramatic, even elegant, form. It was not a racecar and only barely a sports cars as completed. It was a Ferrari-powered sculpture. So be it. The elegant Meade machine was a popular addition to the daily parade of predelivery exotics on the streets and surrounding country lanes of Emelia Romagna. When Thomassima II’s bare chassis was first lapping the Modena Aero-Autodromo with non-racer Tom Meade at the wheel a few key members of his cadre of veteran race team pals were present. Tom was not able to recall their full names in a recent interview, but Gigi (electrics and instrumentation), Guiseppi (technician), and Nino (data and suspension setup) arrived for the expected necessity of advice and solutions. The track was free. One simply arranged for brief lapping periods with the teams sharing it that day. After a number test lap sessions with stops for adjustments, it was deemed ready for final fitting of the beautiful Drogo coachwork.

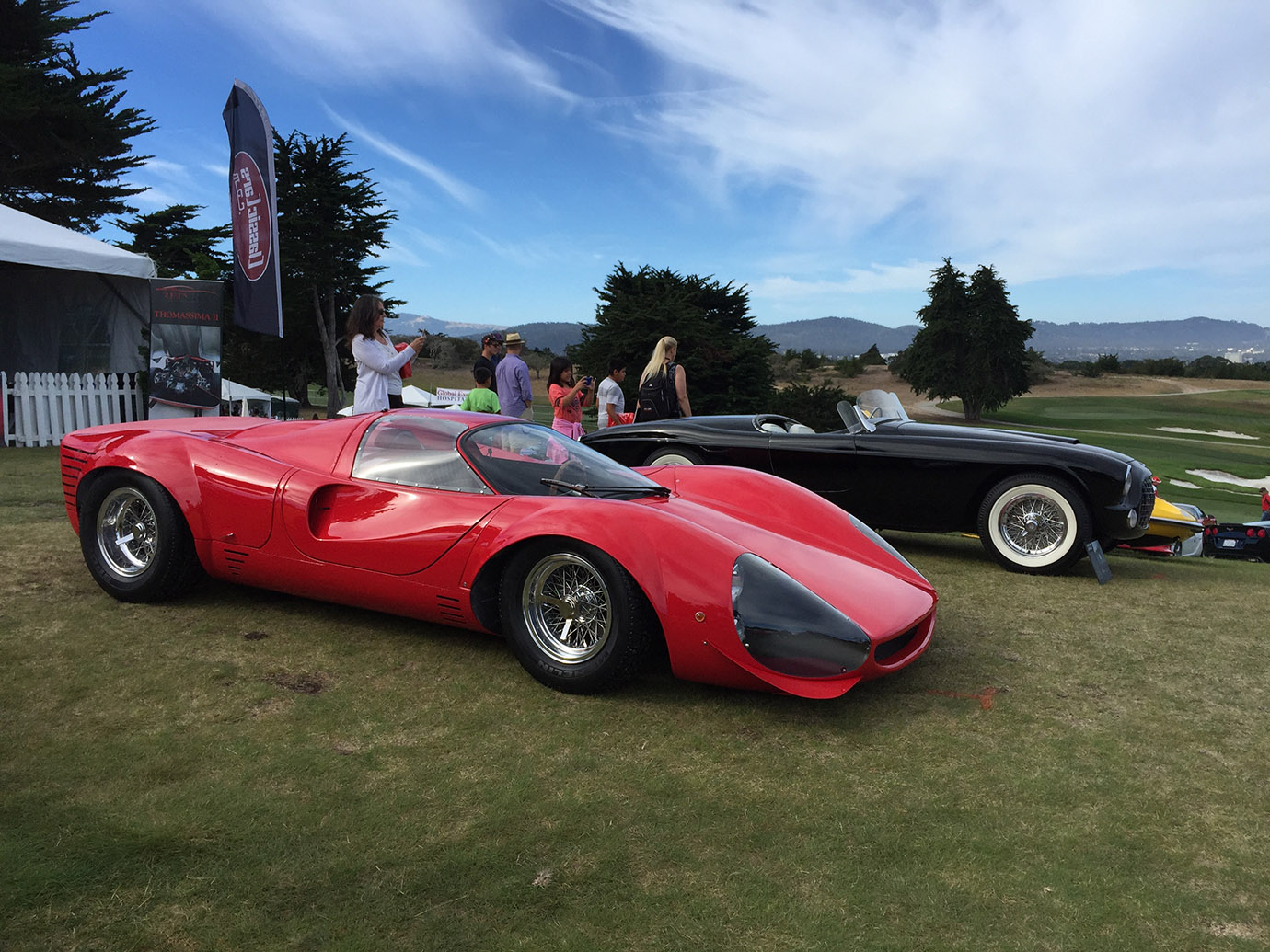

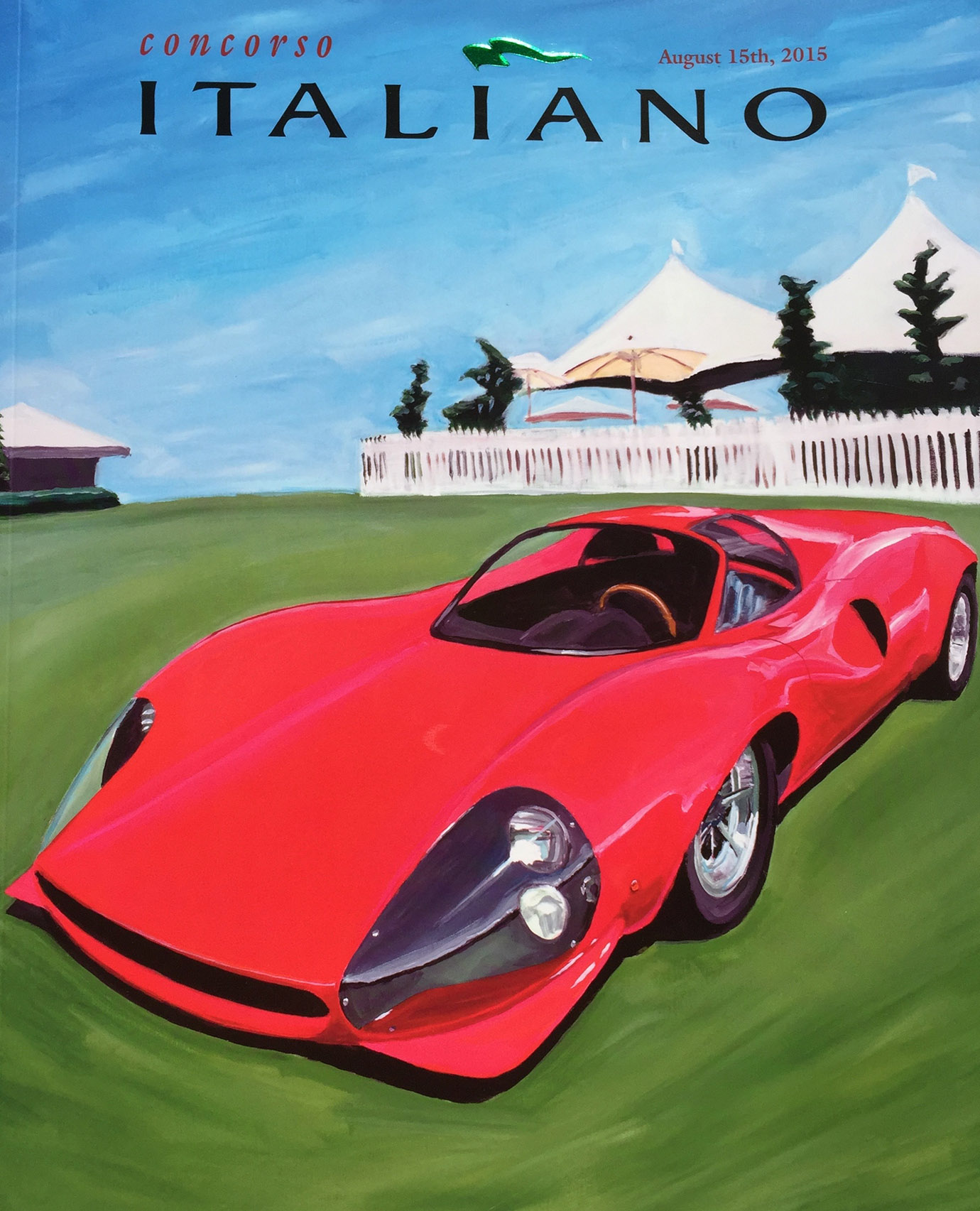

Upon delivery some months later, after multiple revisions by the new owner, the finished Thomassima II was crated and delivered to Windsor’s home in Los Gatos. It travelled by ship, and somewhere in its checkered journey someone had ripped off its protective cover and left its perfect red paint exposed to the sea voyage. That was not the worst, according to Tom, Harry removed the Thomassima badges and had them replaced by Ferrari badges and for the final insult created a new identity with a “250 P/4” badge for the tail. But the newly minted car was curiously invited to Pebble Beach in 1968 where it was exhibited in the “European Sports Cars $4001 – $7000” category as a Ferrari 250 P/4 Roadster. Thomassima II made headlines, made a Road & Track magazine cover, filled countless pages of editorial in many languages, made U.S. television for 60 Minutes and made money — not profit, but enough to make another car. The television crew mounted a camera on one of their cars for some car-to-car filming of Tom making fast laps around the Modena circuit. Then they followed Tom around the Torino Salon where his cars were on display and in doing so created “The Famous American Ferrari Designer, Tom Meade.” The Thomassima II traded hands several times before it’s current owner, purchased the wrecked car in 1983. The most significant damage was to the nose. After several surrendered restorations the incomplete car was delivered to Tim Taylor at Red Car Restorations, Rockwall Texas. Tim was captivated by the history of the car and consulted with Tom Meade on several occasions to maintain the authenticity of the Thomassima II. 43years after it showed at Pebble Beach, the Thomassima II freshly restored was invited to the 2015 Concorso Italiano.

Forever compulsive and fiercely focused, Tom Meade was on a life-long trajectory of creativity; making history, if not friends or wealth. His third complete design effort was another dramatic coupé, he christened it Thomassima III. It was made famous by the most exotic side exhaust system seen to that date; it would be Tom’s “Keeper.” The incredibly swoopy form paid its own way by modeling for a series of models, the most successful of which was a Hot Wheels edition that went international. While enjoying the published acolades, he was never completely comfortable with the public demonstration of that attention and “wealth” was never a personal goal. Once Thomassima III had made itself famous and put funds in his account, Tom went back to the South Pacific as his comfort zone. He spent most of the next two decades living on air and surf in Indonesia. He returned to California in 1993 to share his mother’s final years. She had been responsible for giving him the fairytale life he had enjoyed and one assumes they had much to share. Thomassima III and a treasure of Ferrari chassis and components were locked into a facility secured by his son on the southwest coast of Lago di Como. Tom shared his mother’s modest apartment until she passed, then, alone again and filled with ideas for his next car, slowly filled it with pieces for Thomassima IV including one of the fabulous 333 SP V-12 engines that had more to do with F1 than sports car racing. He died in 2014 with the drawings and a growing number of pieces for his next dream coming together with the help of another talented young designer, builder, Josh Lange, who continues to work toward completion of Tom’s last dream car, Lange now calls Thomassima IIII Lacrima Rossa (Red Tear, his recognition of Tom’s last great struggle). The design includes a carbon fiber chassis with seats molded into the tub, much like the Thomassima II. The instruments will be multi-level, multi-functional and hand made like most of the car’s details. An aluminum body to Tom’s careful design will follow the Meade tradition. While a close friend of Tom for the last few years of his life, Lange shares less of the obesssion and more of a devotion to the last testament of Tom Meade.

Debates will continue about the Tom Meade automotive style and even more about his personal style, but there can be none about his accomplishments. He set out to own an Italian racing car to drive on the street and developed into a legendary builder of very personal automotive statements. Tom died in 2013.

Credits: thomassima.com by Larry Crane with precious material from the Tom Meade Archive, Marc Sonnery , Edwin K. Niles , Chad Glass, Josh Lange and Tim Taylor