Performance, character and style. Ducati’s design philosophy can be seen in every detail, no matter how small. Aside from -cutting-edge technology, however, the Italian motorcycle manu-facturer would much rather sell good moments. At the launch event for the new -Diavel V4, Ducati Centro Stile Director Andrea Ferraresi told us how.

He also explained why, of all things, the design of a new key has been giving him something of a headache.

The new The Diavel V4

ANDREA FERRARESI was born on July 14, 1968, in Mirandola in the Province of Modena and studied aerodynamics and aeronautical engineering. Since joining Ducati in 2000, all of the brand’s superbikes have been developed with his input as project manager. Ferraresi was appointed director of Ducati Centro Stile in 2005. Since then, all Ducati models – the 1098, the Hypermotard, the Monster, the Streetfighter, the Multistrada, the Diavel, the XDiavel, the 1199 Panigale and the Panigale V4 – bear his signature.

How would you define good design?

Good design is nice proportions, beautiful shapes and attractive details. If the proportions of a motorcycle or a car aren’t just right, there’s no way you’ll end up with good design.

You once said that you were influenced by Walter de Silva’s statement that design is discipline. How so?

For two reasons. Reason number one is because it’s true: design is discipline. And reason number two is, being an engineer without a background in design, knowing that design is a discipline gives me the confidence I need to do my work. Because design is discipline, you have to follow the steps. You have to decide where to go and how to get there. What do you want to design, which model or product families fit to your brand? How do you get there? At Ducati, we have these guidelines we call “reduce to the max”. And we strictly follow these golden rules.

Do you have any other design rules that are etched in stone?

The mass on the front, for instance. When you look at the Ducati Panigale from the side, the 916 or the 1098, you always find that visually the mass of the bike is on the front wheel. Why is that so important? Because when you ride a motorcycle in a sporty way, typically a rider will say they can’t feel the front wheel. But feeling the front wheel is really important. And when you see this mass on the front wheel, your brain immediately recognizes this is sport bike. Another point is the tail. We always adopt a very slim tail – not only on a Panigale, but also on a Multistrada or a Monster. We love this idea of having a big mass on the front and then this slim tail inserted into the main mass. So when you’re sitting on the bike, you see these sinuous lines. The shoulder, the back, the slim waist. This Coca-Cola shape is from Massimo Tamburini from the 916 and we will keep on doing things like this. Or the compactness of the front view, even on bikes that aren’t small. This idea of a racing machine where everything has to be connected, every part must be joined to the other to save space, to have something smaller, to be more aerodynamic. These are the key points that can be changed. The technical part, of course, has to follow the evolution of technology.

While previous generations were more concerned with looking cool, today’s younger motorcycle riders have a completely different set of values. How are you addressing this change?

On this point, I think we’re pretty lucky because Ducati is and always will be a sport tool. When you do sports, you can still be careful and take care of the environment and so on. On a motorcycle, you’re enjoying an experience. I think that the needs from this point of view won’t change that much.

Is it an important step for you that Ducati is positioning itself even more in the luxury segment?

So we decided to adopt this new strategy last year that we are calling “raise the bar” with the aim of moving the company towards luxury. We are following a 360-degree approach here, and not only the product but also the motorcycle lineup will change with this idea of raising the bar. We will be more and more focused on the high-end of the market. We also want to reinforce the sense of pride you feel when you’re part of the Ducati family. As I always like to say: When you buy a Ducati, you’re not just buying a motorcycle; you’re gaining membership in a club, the club of the Ducatisti. And staying with this idea of luxury, for us it is currently very interesting to examine the development of a modern understanding of luxury, which is shifting a lot from the traditional way of looking at things.

How so?

We think that modern luxury is more and more about experiences. Real luxury is taking a moment for yourself to go off to a wonderful place and have experiences with your motorcycle. We want to involve our customers in 360-degree experiences. Of course, riding a motorcycle is the most important part of the experience, but there should also be good food, it should be about visiting places, maybe going to a concert in a wonderful city and so on. That’s our idea of luxury.

Let’s talk about the Diavel V4. Everything about it is somehow unconventional and unique. To what extent is it still consistent with the Ducati DNA?

The Diavel concept is based on the union of three motorcycle types: a superbike, a sport naked and a cruiser. All three motorcycles are perfectly in line with the Ducati DNA. For the superbike and the naked bike, it’s obvious. But even the cruiser is in line with the Ducati DNA, because when you think about it, it’s not a cruiser in a traditional way; it’s a cruiser in a Ducati way.

We especially like the fold-out passenger foot pegs . . .

This was one of the solutions that customers asked us the most about. Another solution that I like a lot is having the front turn signal not in the typical, conventional position on the front fore but in front of a reservoir. So when they’re switched off, you can’t see them. Just the other day a customer came up to me and said, “Normally when I buy a bike, the first thing I change are the turn signals. I throw them away and replace them with smaller ones. But this time, I’m going to keep them.” I was very happy to hear that.

You also completely rethought the way you design the taillight. What was important to keep in mind in the process?

Especially on a bike like the Diavel, a traditional taillight is something that kind of ruins the purity of the tail. What we wanted was to have a bike without a taillight. And the way we solved this problem was to have a totally black tail with holes and an LED matrix. The reflectors have to look black when switched off. That was important for homologation. But they can’t be black, because they are reflectors. So they have to be chrome-plated. The solution was a reflector with a black surface that reflects on the inside. It was quite a challenge that involved many meetings and many hours of discussion.

Who or what inspired you when you were a kid?

When I was a kid, maybe five or six years old, my dream was to become an architect. My mother told me that I was always drawing houses. But then I fell in love with airplanes. That was thanks to my uncle, who was a fighter pilot at the time. He was my hero.

What was he like?

Just think about Maverick in Top Gun. Like every fighter pilot, he was in love with fantastic cars and fantastic motorcycles. I remember this Alfa GT Junior that he had. I was seven or eight years old, and it was like a dream for me. So at that point, I wanted to do something with airplanes. But when you grow up in Italy’s Motor Valley, there’s no getting around motor vehicles. There’s no way to avoid becoming a petrolhead. If you live there and you don’t have a moped at fourteen, your friends will ask what’s wrong with you. [laughs] So I started falling in love with cars and motorcycles. Then, when I was nineteen, I decided to become an aerospace engineer. But my specialization was in aerodynamics for cars. So I found a way to mix my passions. And somehow I ended up in the wind tunnel of Ferrari, testing models for the aerodynamics of cars. I stayed there about one year. They actually let me use the wind tunnel at night. During the day, of course, they had to do their business. It was a really great experience and I am extremely grateful to Ferrari and to all the people who helped me develop my passion for aerodynamics. And then Ducati offered me a position as project manager.

And what was the next big milestone?

The next milestone was in 2005 when they asked me if I was ready to head up the design studio – even though I didn’t have a background in design. There had been a lot of conflict between R&D and the design studio before that. That’s why Claudio Domenicali thought that I, as an engineer, as part of R&D, was the right person to lead the design studio. So I thought, okay, I’m a translator. I’m the one who explains to the engineers what the design is that we want to achieve. And I’m the one who explains to the designers why the engineers think something is not feasible, but that by adapting the design a bit, we can get what we want.

How important is it to talk to other designers? You’re good friends with Mitja Borkert, Lamborghini’s head of design . . .

Yes, I have a really good relationship with him. We’re real friends. I often call him and say, come over to Bologna, I have something for you. He’s a Ducatista. He owns a Ducati. So he also knows his way around motorcycles. His opinion is very important to me. He has the point of view of a car designer that knows perfectly how motorcycles function. That’s pretty important. The other way around, I also think that my opinion is important to him because it is the opinion of someone who likes cars but is not involved in all the processes, constraints, the platform and so on. I think he appreciates the freedom that I use in evaluating his models.

Does motorcycle design exert an important influence on the design of sports cars or hypercars?

It does, especially because of this attitude that we have for lightweight design. We are almost obsessive in our quest to save every possible gram of weight. A few years ago, when we launched the Superleggera, we explained how we saved sixteen grams on the water radiator cap by moving from steel to aluminum. I mean, it was just sixteen grams, but we were excited! At the moment, we’re working on designing a new key. But currently it weighs around ten grams more than the old one. And so I have to decide. Ten grams more, for a key? I don’t know what to do. But I’m sure you’ll find out soon enough how this story turns out.

Interview: Nadine Hanfstein for ramp

Photos: Ducati

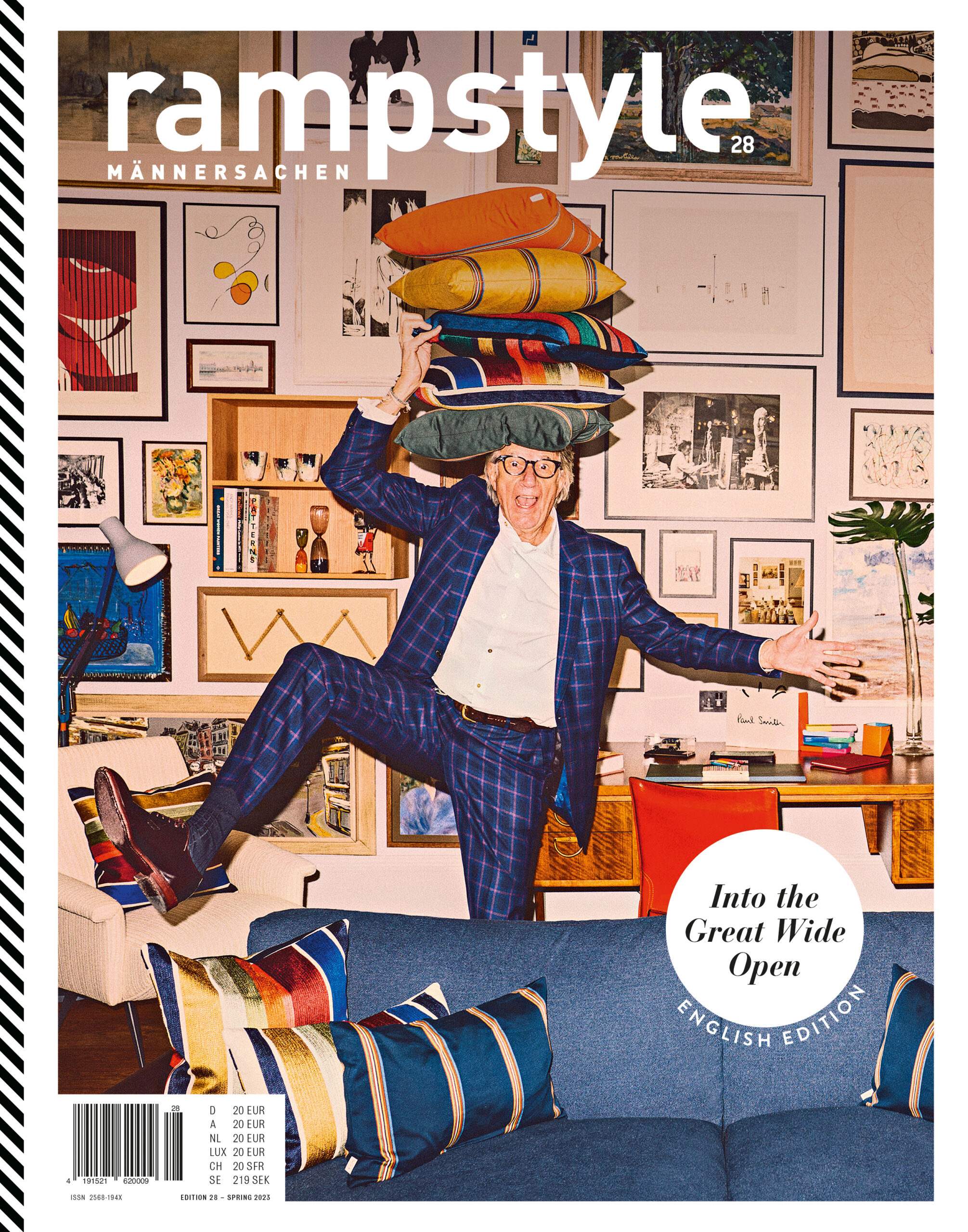

rampstyle #28: Into the Great Wide Open

An exclusive fashion editorial with Tim Bendzko. Unseen pictures by photographer Anouk Masson Krantz. A conversation with star director Guy Ritchie and a somewhat different interview with musician Dan Auerbach. All this and much more awaits you in this issue of rampstyle. Find out more