The economics facing the postwar car industry in the U.K. were complex and challenging. The country was nearly bankrupt, and it had to sell its manufactured products abroad in an “export or die” model. The U.S., with its booming economy and desirable dollars, were an obvious target for British goods. Carmakers like MG, Austin-Healey, Jaguar, Sunbeam and Triumph certainly did sell a good number of cars here in the postwar years, but the margins were never that great and so R&D budgets were never huge for any British sports car maker.

All therefore became adept at doing the most with the least, and it was in this spirit that the Triumph Spitfire was born at the beginning of the 1960s. Forty-five years after the last Spitfires were built, their appeal is still much the same. They’re handsome and fun while also being cheap, relatively simple, easy to work on, and plentiful. However, as with any classic car, there are things to keep in mind when shopping for a Spitfire.

The Spitfire mostly owes its existence to original “Bugeye” Sprite of 1958, and the subsequent badge-engineered MG Midget/Austin-Healey Sprite twins that became the Spitfire’s main rivals in the ’60s. The Sprite had opened up a new market segment for people who wanted a genuine, capable roadster but didn’t have the coin for anything currently in showrooms, including Triumph’s TR-series. Triumph therefore rushed to build a pint-sized sports car of its own but, most British carmakers of the day, resources weren’t there for a clean-sheet design and many components were recycled from the company’s existing models.

For example, while many other sports car companies were transitioning to unibody construction, Triumph was forced to retain separate body and chassis architecture, turning to its small Herald sedan as a jumping off point. Its steel backbone chassis could be easily shortened, and its outriggers eliminated to lower the center-of-gravity. Frequent Triumph collaborator Giovanni Michelotti designed a low-slung, curvy body and Triumph engineers managed to give it front disc brakes and a more highly tuned, dual-carb version of the Herald’s 1147 cc pushrod four-cylinder. Now, all it needed was a name. For that, Triumph grabbed maybe the most hallowed one in the country—Spitfire. Standard Triumph had named their dainty new 63 horsepower sports car after the fighter plane that won the Battle of Britain, and it missed the anniversary of the battle by two years (debuting in the fall of 1962 as a 1963 model), but few people took issue with that.

Like the early Sprite, the original “Spitfire 4” (later retconned into the moniker “MK I”) was a very basic car with an erector set top whose frame you had to assemble, and rubber floor mats in lieu of carpeting. Even the instruments were set in the middle of the dash to make it easier (and cheaper) to build left- and right-hand-drive versions. The option list was small—big items were wire wheels, electric overdrive and a pretty, rounded hard top. One thing that wasn’t substantially changed from the Herald, however, was its rear suspension. Those meager R&D budgets mentioned above meant that Triumph’s independent-rear-suspension setups were generally crude, and the Spitfire used swing-axles and a transverse leaf-spring for a lower link. Since there was a universal joint only at the differential, going into a corner too hot could result in sudden extreme positive camber called “jacking,” leading to a violent spin.

On the whole though, the Spitfire was a very pretty, economical and generally pleasant small sports car that was in many ways regarded as superior to its Midget/Sprite (aka “Spridget”) rivals. Testers praised the quick and precise steering, the brakes, the 30+ mpg fuel economy, and the fact that the entire front-clip opened to give easy access to the engine and suspension. The 0-60 times were largely theoretical, if you were patient, you could do it in about 15 seconds and the Spit’s top speed, if you were even more patient, was about 90 mph. At just under $2200, it cost about the same as a very basic American sedan, or the equivalent of about $23,000 in today’s money.

The 1965 MK II was only subtly changed from the original car—it had a few more horsepower, and a slightly more finished off interior, gaining actual carpeting for the first time as well as a revised grille. It was the last version of the car to retain Michelotti’s original and very pretty design. Mandatory bumper height laws meant that the new MK III, which started hitting U.S. roads in 1967, had an awkward and crudely raised front bumper. Some likened it to a dog with a bone in its mouth. On the plus side, the MK III was the most powerful Spit sold in the U.S., with a 1296 cc 75 hp engine, and 0-60 was less excruciating at about 13 seconds. The top speed was just shy of 100 mph. An actual folding convertible top and a wood veneer dash were also added and for safety purposes, the U.S. mandated a dual-circuit braking system.

The new decade brought a new Spitfire, the substantially redesigned MK IV, also styled by Michelotti. In front, the point of the bonnet was moved slightly down to close the gap between the nose and the bumper (which was itself a bit smaller) and the grille was now completely below the bumper and the pronounced panel join lines on the hood were eliminated making for a much smoother design. The rear was chopped off Kamm-style to resemble the Triumph 2000, Dolomite and Stag models. A new, more glassy hardtop was also a fairly common option.

But the real change was to the rear suspension. Instead of rigidly mounting the entire spring to the differential, only one leaf was attached to the diff, allowing the spring itself to swing a bit, moderating the extreme rear camber changes. A simple change, but it worked wonders. The British magazine Motor Sport had this to say: “The handling is now beyond reproach and sudden changes of direction can be achieved much more predictably than before.” That was essentially gushing in 1970s British auto journalism. A wider track (made obvious by slightly flared fenders) helped too.

In the U.S., small-displacement engines were getting decimated by new U.S. emission regulations. Companies with the luxury of big budgets like VW could get creative and employ things like fuel-injection to clean up tailpipe emissions without sacrificing power. But at the chronically shaky British Leyland Motor Corporation, the best the engineers could do was increase the engine’s displacement, lower compression, restrict how much fuel is going through it, and hope for the best, which is what happened in 1973.

The new stroked Spitfire 1493 cc engine (rounded up to 1500 by the marketers), which now relied on a single Zenith-Stromberg carburetor felt agricultural and nowhere near as revvy as the smaller displacement engines. Power was listed officially as 57-hp but this is somewhat misleading as the U.S. had made the switch from SAE gross, to SAE net horsepower so in practice, the bigger 1493 cc engine was probably making somewhere around the same horsepower as an early 1296 cc car. One can only imagine how entertaining the Spitfire would have been with something like the 80-horsepower, fuel injected overhead cam four that was powering the contemporary VW Scirocco. Speaking of the Scirocco, the superiority of a modern hot hatchback to aging British sports cars wasn’t lost on road testers of the 1970s. Cars like the Spitfire and the Midget became harder sells, often turning up as prizes on gameshows like Let’s Make a Deal and The Price is Right.

Cosmetically, the Mark IV refresh was the last major overhaul for the car which ended production in 1980 after over 325,000 copies were built. Post-1972 U.S. bumper regulations did mandate massive rubber overriders and a stouter rear bumper. For the last two years, the chrome part of the bumper went away in favor of the rather unlovely one-piece black rubber units front and rear that made the car’s already fairly generous overhangs look comical. And that was it, the Spitfire went away in 1980, followed the next year by the TR7 and the TR8. Triumph, a storied British marque, was done forever in the U.S.

What to Look for

Everything mechanical on these cars is both available and inexpensive. So, first and foremost, rust is what you need to look for in a Spitfire. And it can set in virtually anywhere. Sills, fender arches, trunk floors, main floors, even cowls and windshield frames and of course, the backbone chassis itself are all potential trouble spots. Since no Spitfire is worth much money, any significant rust in any of these places puts one of these cars beyond economical repair.

Hydraulics, meanwhile, are pretty cheap and straightforward. A soft clutch means that the clutch master cylinder or slave cylinder seals are shot. Soft brakes should have you checking the brake master cylinder, front calipers, rear wheel cylinders, and brake lines.

The 1147 and 1296 engines are fairly stout. Smoke and low oil pressure are obvious bad signs, and it is essential to use the right oil filter with a non-return valve to prevent damage from oil starvation on startup. Cars that clatter on startup are generally in need of crankshaft bearings. The 1296s suffer from the same thrust washer issues as a TR6. If you grab the pulley, and there’s any in/out play at all, these need immediate attention. Like anything else, differentials and gearboxes get whiny with age and snychros and overdrive solenoids fail. Working O/D is a huge plus on any Spitfire that sees even a little highway use. The Austin-Marina gearboxes on 1500 cars have a better reputation for durability, the engines less so with ring and crankshaft wear not uncommon. Poor idling or flat-spots are very often solved by no more than replacing the rubber diaphragm in a Zenith carb or filling its dashpot with oil. A freshly rebuilt carb, however, can do wonders for a car’s drivability.

Spits were built during an era where grease fittings were a thing, and front suspension trunnions would wear out quickly without regular shots of grease. Luckily, everything is easily accessed and easy to repair with the exception of wheel bearings, which are a pain in the rear for DIYers. Rear suspension woes are usually just garden-variety leaky shocks or a sagging leaf spring. Electrical issues are often just frayed wiring and corroded grounds and connectors or components like the starter or alternator or generator simply wearing out. A GM single-wire alternator conversion and a modern high-torque starter are good things.

Spitfire interiors are very wear-prone, but honestly, you could do a complete refurb in a weekend, including seat covers, door cards, side panels and carpet for less than $2000. Later cars had lovely houndstooth cloth inserts that were much more bum-friendly. Want a new wood veneer dash? That’s another $240. The main thing generally missing in engine compartments are the splash shield/valence boards that fit behind the wheels. These were made out of a heavy-duty cardboard-like material and were usually gone in a few years. Reproductions are available, but if you’re looking at a Spitfire with its original set, you have a unicorn on your hands. Spitfires were available in a great assortment of ’70s period colors like Java Green, Magenta, Inca Yellow and Topaz Orange. All of them look great. A bit of trivia: A Pimento Red Spitfire makes a few prominent guest appearances in the Netflix series “Emily in Paris.”

What to Pay

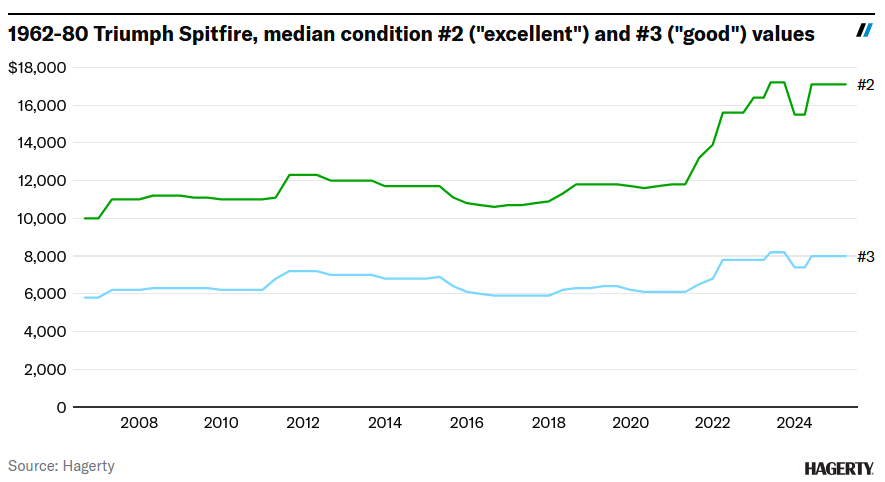

Despite some significant differences and a production run that spanned nearly two decades, all versions of the Spitfire are worth within a grand or two of each other. Current condition #2 (“excellent”) values in the Hagerty Price Guide range from $16,600 to $17,400, and condition #3 (“good”) values range from $7300 to $8200. A perfect show-winning car or a low-mile creampuff with all the good options can stretch past 20 grand, but not by much.

Expect to pay a premium for rare colors or for desirable options like a factory hardtop and overdrive. Since Spitfires are relatively cheap no matter what condition they’re in, it’s a better idea to pay more for a solid car now than to buy a cheaper one with needs. That said, if you’re in search of an economical and straightforward project car, a scruffy Spitfire can be rewarding.

Other than nostalgia and sheer cuteness, though, it’s hard to make an objectively compelling case for Spitfire ownership today. They’re tiny, especially when sharing the road with large pickups SUVs, and they struggle to keep up with modern highway traffic. In most respects, an NA Miata is a far more practical proposition. But since practicality rarely enters the picture when buying any vintage sports car, and Spitfires remain very reasonably-priced and cheap to maintain, it’s hard to deny the attraction.

Report by Rob Sass

find more news here.