Andy Wallace is the fastest driver in the world. He holds the speed record for street-legal production vehicles at almost 500 km/h in a Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+. So we just had to talk to him about the sensation of travelling at extreme speeds. In a Chiron Super Sport, of course. And, of course, the location was perfect as well.

Berlin in August. Potsdamer Platz, a light drizzle. Rush hour. A delivery van passes by, pedestrians cross the street, cyclists looking for the next adrenaline rush when turning. A motorcyclist looks for and finds a gap. A rental car would certainly be the most sensible choice here, nothing special, just a halfway good engine and as solid as possible, true to the motto: “Don’t be gentle it’s a rental!”

We’re driving a Bugatti. A Bugatti Chiron Super Sport. Almost 1,600 hp, 440 km/h top speed, the maximum torque of 1,600 Nm makes its presence felt at a low 2,250 rpm. Currently the fastest production car in the world. Okay, so our Chiron is just a “normal” Super Sport, not one of the thirty limited-edition special models built on the basis of the prototype with which Le Mans winner and Bugatti test driver Andy Wallace blazed his world record into the asphalt almost exactly three years ago. With a top speed of exactly 490.484 km/h (304.773 mph), Wallace broke the magic barrier of three hundred miles per hour. The reward was said special series, each one in exposed black carbon fiber with orange stripes and a proud “+” at the end of the model designation. You could do worse. Speaking of which, Bugatti dutifully limits the Chiron Super Sport at 440 km/h – for safety reasons, they say.

Okay, but because ultimately the Chiron Super Sport and the Chiron Super Sport 300+ differ only in terms of sharpened configuration, we’ll just blithely stick to our assertion that we’re driving the world’s fastest production car. What’s more, it’s also black. Carbon black. For a car worth around three million euros, that’s dangerously inconspicuous if we want to survive the wild rush-hour jostle in Berlin as adequately as possible.

To make sure that the conditions were right for his 2019 record-breaking attempt, Andy Wallace approached the top speed in 50 km/h increments starting at 300 km/h. In Berlin, I’m bravely trying to reach 50 km/h. That would be my top speed for the day so far. And it seems unlikely that I’ll be able to do much more than that today. At least I’ve got a cheerful, relaxed Andy Wallace sitting next to me. Behind us to the left a taxi honks its horn, to the front and right a mountain bike passes us with a safety margin of just half a meter. The perfect setting to talk about high-speed experiences.

The Bugatti Chiron makes it easy to drive fast. Do you go to work in the morning and think to yourself, “I haven’t got any appointments today, I’ll just go drive 500 km/h on the test track?”

Not quite. The way that actually works is a bit different. Every new speed record starts with the wheels and tires. The important thing is to be aware of the physics behind the speeds. As the wheels turn, they generate forces. At 420 km/h, there are 3,000 g tugging at the tire. These forces affect everything, including the temperature and tire pressure sensor, for example. It weighs 40.4 grams. Calculated for 3,000 g, that’s around 130 kilograms of force pushing outward. The first thing we do is we go to a company in the U.S. that, among other things, tests the tires for the Space Shuttle, because they’re the only ones who can simulate these kinds of speeds in the way that we need. They run a relatively complicated program of different speeds up to and over 500 km/h.

And?

We found that the tire from Michelin works quite well for the Bugatti Chiron up to 500 km/h. But at Bugatti we’re not satisfied with building a car that can travel at almost 500 km/h, and everything around it is designed to just make do. We want to make sure that everything is as safe as possible. So what did they do? Before the final layer of rubber is applied, ultra-thin nickel threads are wrapped around the tire in the direction of travel. It’s still a Pilot Cup, but it’s coded BG2. This is the homologated standard tire for the Bugatti Chiron Super Sport. For a record-breaking attempt, Michelin brings along eleven sets of these tires.

Besides the tires, aerodynamics must certainly play an important role as well.

Absolutely. That’s the second crucial factor in a speed test like this. To achieve the maximum possible speed, we need to drive with as little downforce as possible. Almost none. To put it another way: The Bugatti weighs around 2.5 tons, and the aerodynamics at top speed pull it upward with almost the same force, so the car is more or less weightless. If we were to drive with more downforce, this would put more pressure on the tires, which would increase the rolling resistance and reduce speed. All of this work is done in advance in the wind tunnel or in simulations on the computer. Then, when we come to the test track, the first thing we do is to check all the data that we had previously calculated and simulated. We measure everything with the car standing still, do a lap, come back, measure everything again, go out once at 70 km/h. That way, we make sure that all the instruments are working properly. Only then does the actual program begin, which also consists of several speed runs.

You approach the limit from below?

That’s right, we gradually work our way up: 100 km/h for about fifteen seconds, 150 km/h for fifteen seconds, 200, 250. In between, the data are constantly checked and compared. The downforce between the front and rear axle could suddenly change, for example, with zero downforce at the front but some at the rear. Sometimes we then work on the car for up to half an hour before moving on to the next lap. The process of taking a car to 450 km/h is a very long and painstaking one. We go through all the data again and again until we can say, “Okay, now let’s go out and do 450 km/h for ten to fifteen seconds.”

And what’s that like?

It’s really easy to fool yourself, especially in a Bugatti Chiron Super Sport. It still feels relatively comfortable.

You probably still have a few kilograms of downforce left over, don’t you?

Yes, slightly more than 100 kilograms on both the front and rear axle.

So you only become weightless above 450 km/h?

It’s not really weightless. There are two tons of dead weight pulling the vehicle to earth, and there are two tons of aerodynamics pulling it upward. The car is subjected to enormous forces.

If the car suddenly experiences lift, does that make itself felt beforehand? Can you anticipate that?

No. The car takes off, does an uncontrolled backflip, and that’s that.

Not a chance?

Not a chance. It happened to me twice in a race car, never with a Bugatti. And both times it didn’t announce itself. The car simply goes up into the air.

What’s the tolerance here?

The car is five millimeters lower at the front axle than at the rear. If this changes by ten millimeters at 490 km/h, meaning the car is suddenly five millimeters lower at the rear than at the front, it’ll take off.

Five millimeters?

Five millimeters. That’s pure physics. We took a close look at all aspects of high-speed driving, and the risk cannot be reduced to zero. What we do is we design the drive the way you would build a pyramid. And like a pyramid, we start with a broad base and work our way through all the factors up to a small peak of residual risk at the end so we can carry out the drive with a maximum of safety. If a rear tire suddenly loses pressure at 490 km/h, for example, the car will rise up at the front. That’s why we spend several hours beforehand clearing the test track of every little stone we can find. The preparations take months.

How do you as a human being prepare for speeds approaching 500 km/h?

As a racing car driver, I always stayed below 400 km/h – even in the late eighties at Le Mans, when there were still no chicanes on the Mulsanne Straight. So I’m very familiar with speeds of over 300 km/h up to 350, 360, 370. I’ve also done 380 km/h in a Chiron without Speed Key on more than one occasion. Before these drives, I’d only driven 420 km/h once or twice with Speed Key. So what did we do? A week before the drives, they gave me a Chiron, removed the speed limit, and I took it onto a test track. Just for me, to get a feel for it. The amazing thing was that the moment I went from 420 km/h to 430 km/h was really impressive. You think to yourself, it’s just ten km/h more – and that at 420 km/h. It’s totally mad.

Why is that?

I don’t know. Maybe it has to do with the way the human brain works. If you’re driving 200 km/h on the autobahn, that’s a pretty decent cruising speed. If you then accelerate to 240 km/h, that’s twenty percent more, but it’s a completely different story, it feels like so much more. And this effect becomes even more pronounced at higher speeds. When you go from 300 km/h up to 330 km/h, mathematically that’s only ten percent more, but the perceived increase is huge. It’s crazy, because although the increase is linear, the faster the absolute speed, the crazier it gets for the human brain. So I drove a Chiron over 420 km/h, 430 km/h off and on for one whole weekend, and it was okay. It felt good. But after that weekend I had to go to Monza for testing and I had a VW Polo that would do about 200 km/h tops. And I remember sitting at the wheel and thinking to myself at 190 km/h that I could open the door and just run alongside. That’s how slow it seemed to me. That’s when I realized what effects these speeds have on the brain.

How do you explain that as a racing driver?

I don’t have a scientific explanation, but I think that at some point the brain starts to select stimuli and, as if in a kind of box, only perceives what is really important for the moment. This results in a sort of habituation to speeds, even at speeds exceeding 400 km/h. If you then drive more slowly, the brain continues to function in this high-speed state for a while before it adjusts to the new situation.

What does control mean to you?

If I do something and the car responds the way I would expect, then everything is okay. Even above 480 km/h.

What makes the Bugatti Chiron Super Sport special?

I think that every supercar and hypercar has its own personality. And so the Super Sport, with its longer body, is obviously quite different from a normal Chiron. But what distinguishes both from all the others is the engine: sixteen cylinders, four turbochargers. And a power output that is unheard of in a production car with internal combustion engine. Plus the top speed of almost 500 km/h. At the same time, this extreme vehicle is actually very easy to drive. It’s not noisy inside, and when I drive a Chiron for ten hours straight, it doesn’t feel like work at all. It’s completely relaxed. That’s the most fascinating thing for me. There are cars that deliver unbelievable performance, and there are cars that are incredibly comfortable to drive. The Chiron combines the two. Even at top speed, there’s no vibration or excessive noise. And here in the city, it simply cruises along in traffic, without any problems or effort.

Do you ever experience something like fear when a customer is driving who is not so good?

You quickly get a feel for how good a driver is. And after a few kilometers, you also sense how a driver deals with certain dangerous situations in traffic. Does he notice certain things, does he understand the complexity of the situation? Things like that. And to be honest, in regular traffic it’s mostly about not getting stuck on the curb or hitting another car. On the track, it’s a little different. I’m sitting on the wrong side, but ultimately I can still intervene.

Have you ever been at the limit yourself?

I was sitting in the car with a customer once, and on a turn I grabbed his steering wheel when I realized that he was losing control and that we would go flying off otherwise. He was pretty pissed off in the pits afterward that I had intervened, but later he went out on his own and crashed at that exact same spot. He asked me how I had known. I’m not any smarter than the other guy, but the difference between a good driver and a not-so-good driver is often just a thousand miles of experience. I’ve been doing this for a long, long time, and that’s when you develop a feel for a car. It’s not any special skills that I have, it’s just a lot of experience.

I was driving in city traffic earlier with only one hand on the wheel. You never do that. Not even when driving at a crawl . . .

That also has to do with experience. Of course, a Chiron makes it easy for you to steer it with just one hand in city traffic. But I always want to be able to react. If a tire blows out at high speed, I can react better with both hands on the wheel.

How do adrenaline and fear go together?

As a racing driver, it’s relatively simple. If I’m at Le Mans and I hold back when things might get a bit tricky, I lose time. But that’s not what the team wants. On top of that, you tend to avoid risk more the older you get. That’s why most of us slow down as we get older.

What do the numbers mean to you?

I know that, ultimately, the driver is actually the least critical part. I’m just sitting at the wheel, pushing down the pedal and steering. But if someone from another discipline made a mistake beforehand, it can have drastic consequences. So I’m always happy when everything works out and we were able to get the maximum out of it.

How much power does a sports car need?

In English we have a saying: “horses for courses”. It depends on which road you’re driving on at the time. There are so many different types of cars. On a very narrow, curvy country road, you don’t need more than 300 hp to 400 hp. On the other hand, if you’ve got a nice stretch of autobahn in front of you, without a lot of traffic, then things can quickly get boring unless you’re driving a Bugatti Chiron Super Sport. [laughs] But seriously, so many factors determine whether driving is fun or not.

Wallace tells us later that driving a Bugatti you really can collect a lot of phone numbers. With other sports cars, women are more skeptical, he says, but if you drive up in a Bugatti, it’s probably not leased. That guy’s really got money, they think.

That’s also fun.

Text / Interview: Michael Köckritz

Photos: Matthias Mederer/ ramp.pictures

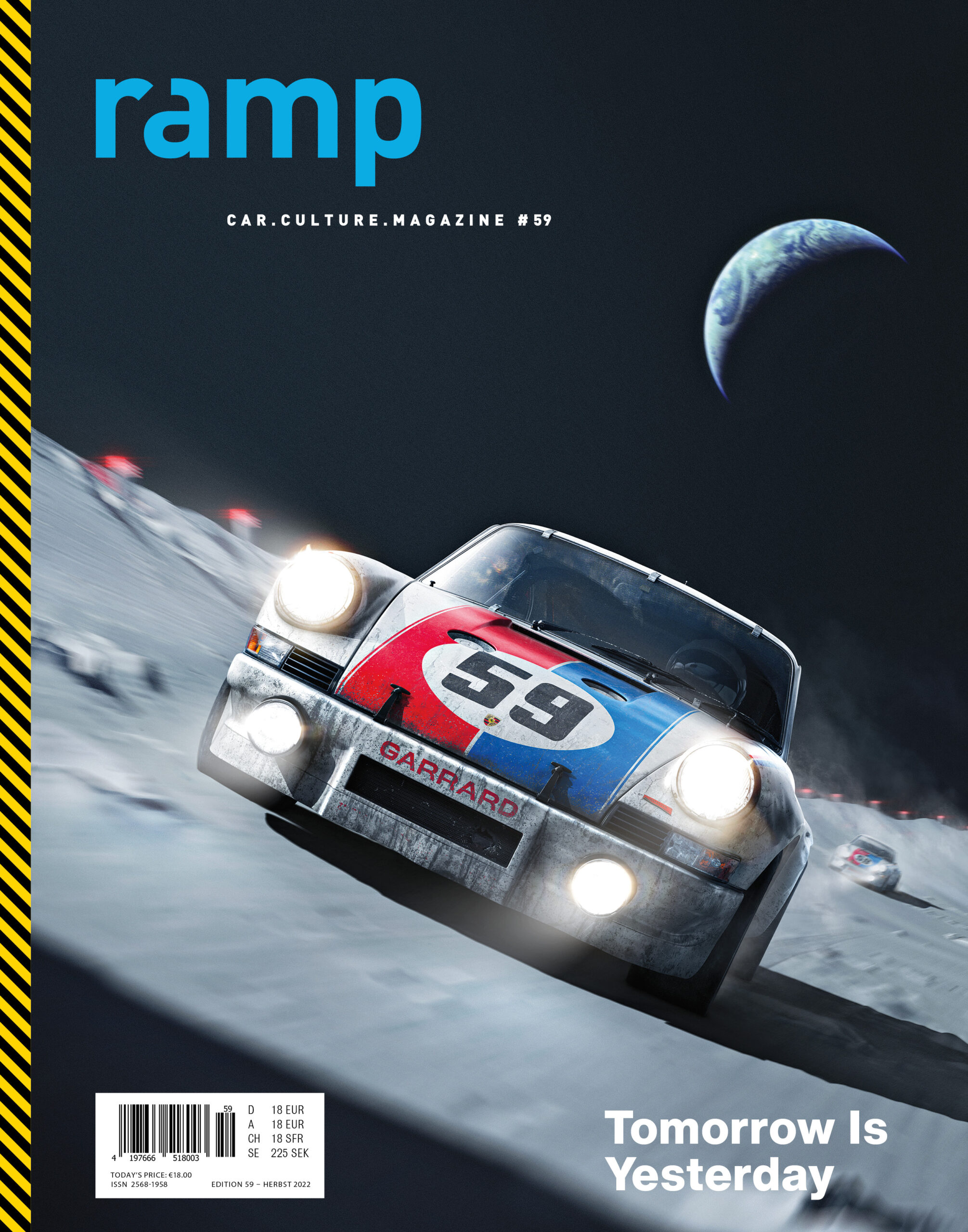

ramp #59

As a high-impact multimedia brand that takes an all-encompassing, end-to-end approach to publishing, ramp is an absolutely authentic expression of quality, integrity and excellence. Its trailblazing luxury magazines, recognized with numerous awards over the past 15 years, have been celebrated for their cool and unconventional, not to mention inspiring and pioneering style, since day one.

ramp, the lavish and beautifully designed coffee table magazine, celebrates the enthusiasm for cars and driving in a passionately subjective, personalized fashion.

Immediate, authentic, intense. Fresh perspectives, avant-garde imagery, with a fine feeling for nuances and the right dramaturgical mix. Always new, always stimulating. Automotive passion infused with a lust for life. The automobile in new, exciting and intense contexts, precisely tailored to the relevant target group, presented in relation to music and fashion, culture and lifestyle, design and art, science and philosophy.