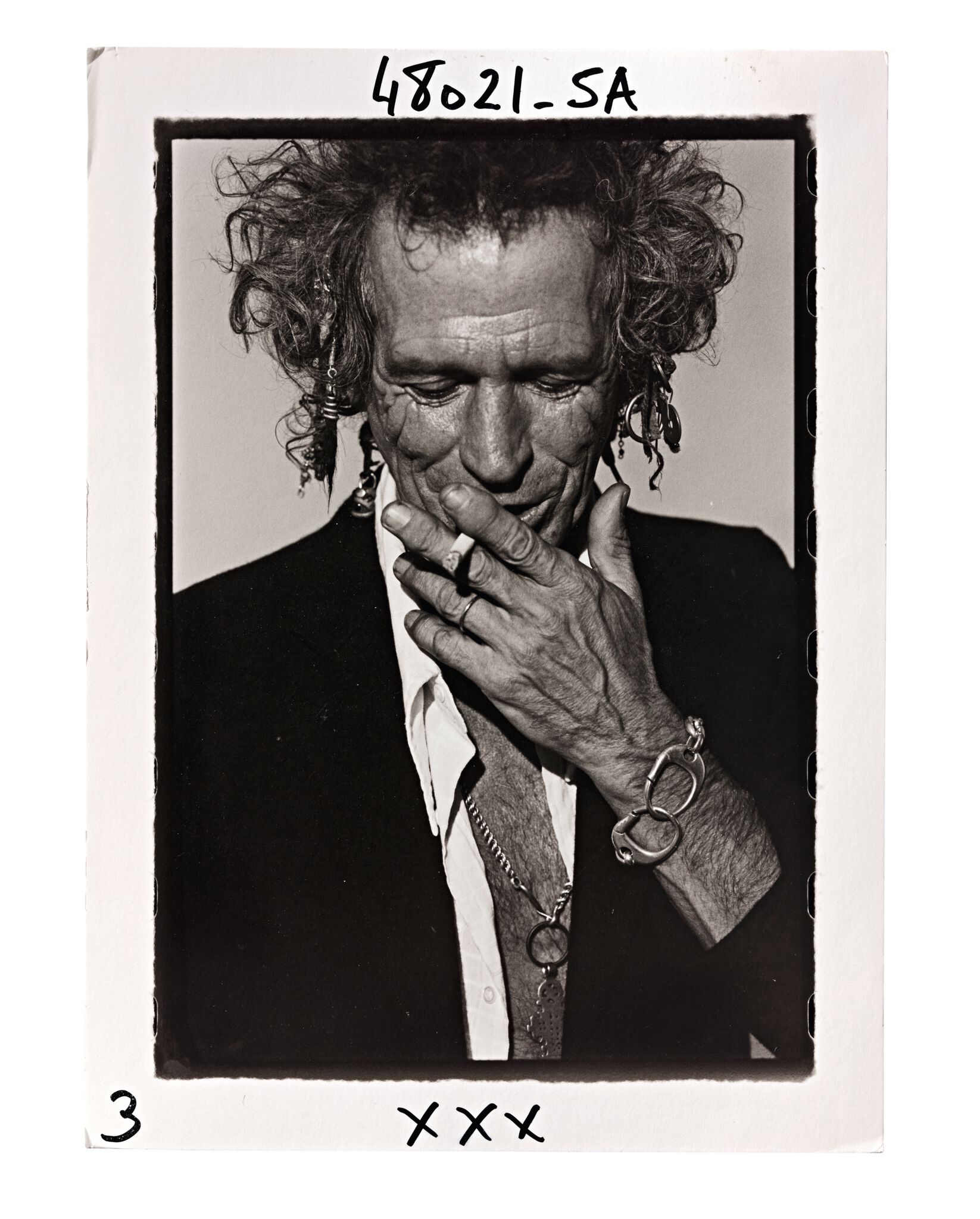

Once described as the “stealth stylist of the British music scene”, Jo Hambro has dressed pretty much everybody who is anybody in this business. An example: She created Keith Richards’s famous pirate look.

The British stylist and creative director doesn’t usually give interviews. Which is why we consider ourselves especially lucky to have been given the privilege of speaking with her.

You started your career at British Vogue in 1979, you were creative fashion director at British GQ from 1992 to 2015, you have spent three decades working with some of the world’s greatest photographers – and you’re still going strong. What motivates you? What drives you on?

Passion and curiosity drive my engine of creativity. I always have a visual image in my head that I am hugely enthusiastic about bringing to life. That’s what drives me: passion. And I think that applies for everything that you do in life. But, as you know, it’s different for everyone.

And what’s your passion?

Well, I get my inspiration from life, from nature and from light. I mean, literally, it could be a walk in the wood; all of these things inform my work. Elton John and David Furnish, who are long-time friends and collaborators, coined the phrase “passion editor” because all three of us are so committed to producing work of the highest quality.

Photography has always played a major role in your life. What makes a good photograph?

In my opinion, it’s very subjective. But for me, I’m a storyteller. I love stories. Something has to capture my imagination. As a little girl, I was a daydreamer and I still am. I recall my teachers were always saying, “Jo spends too much time daydreaming. She stares out of the window.” I realize now that that’s my process. I’m a dreamer.

And what makes a good story?

I think there is an art to good storytelling. When I look at a picture or a painting, it’s almost as though I want to climb into it. And a good story is when you’re transported into another world. It takes you to another place. It’s automatic for me, it’s a normal thing, because I love being transported into different worlds. But there’s not one way. By the stories in my book, you kind of realize that you meet people who are like-minded. I think of myself as an outlaw within the industry. And the photographers who I work with are renegades too. We like to think differently.

And how would you describe the process of storytelling?

I can only compare it to being a musician, and when you’re with other musicians you start jamming together. In fact, it’s the key with anything you do: it’s the team. If you work with people who are like-minded, then suddenly this wonderful thing evolves. I remember Peter Lindbergh saying, “Jo, it’s not just me who takes the picture. It’s the team.” It’s a great stylist, it’s a great assistant. It’s a great hair and make-up artist. Like a band, you’re all playing your special notes, and when it comes together, you create magic.

Let’s talk about your book, how did that come about?

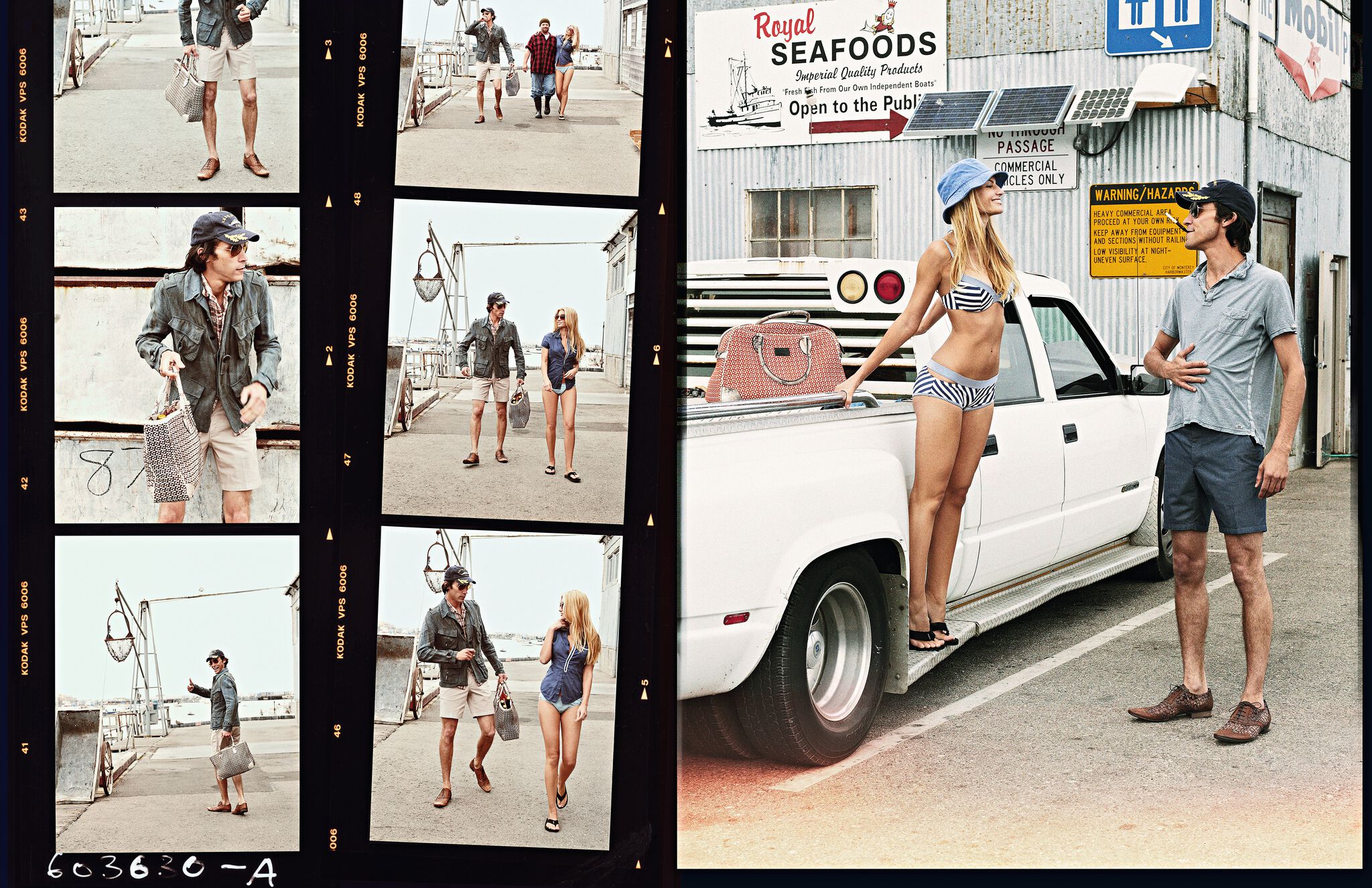

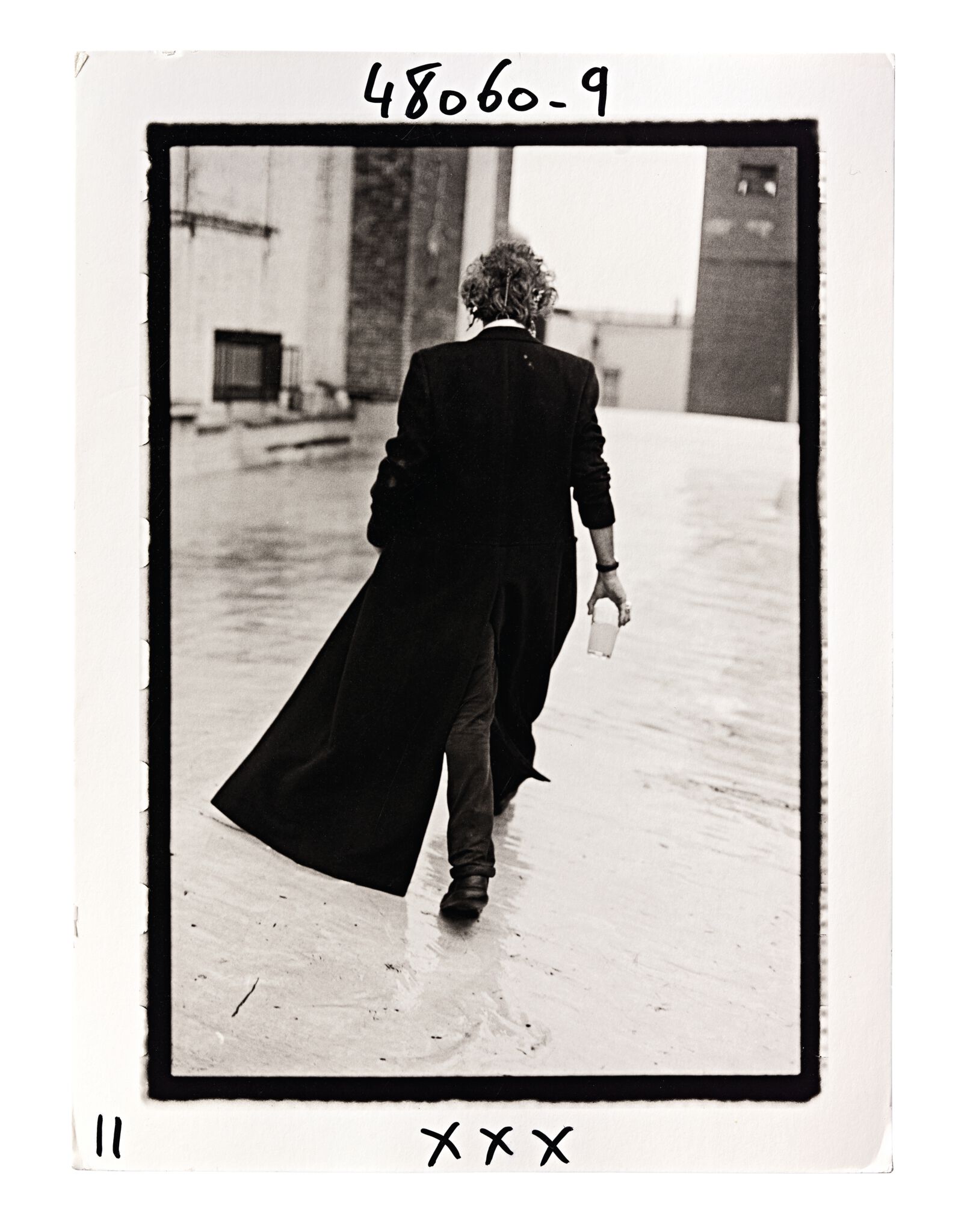

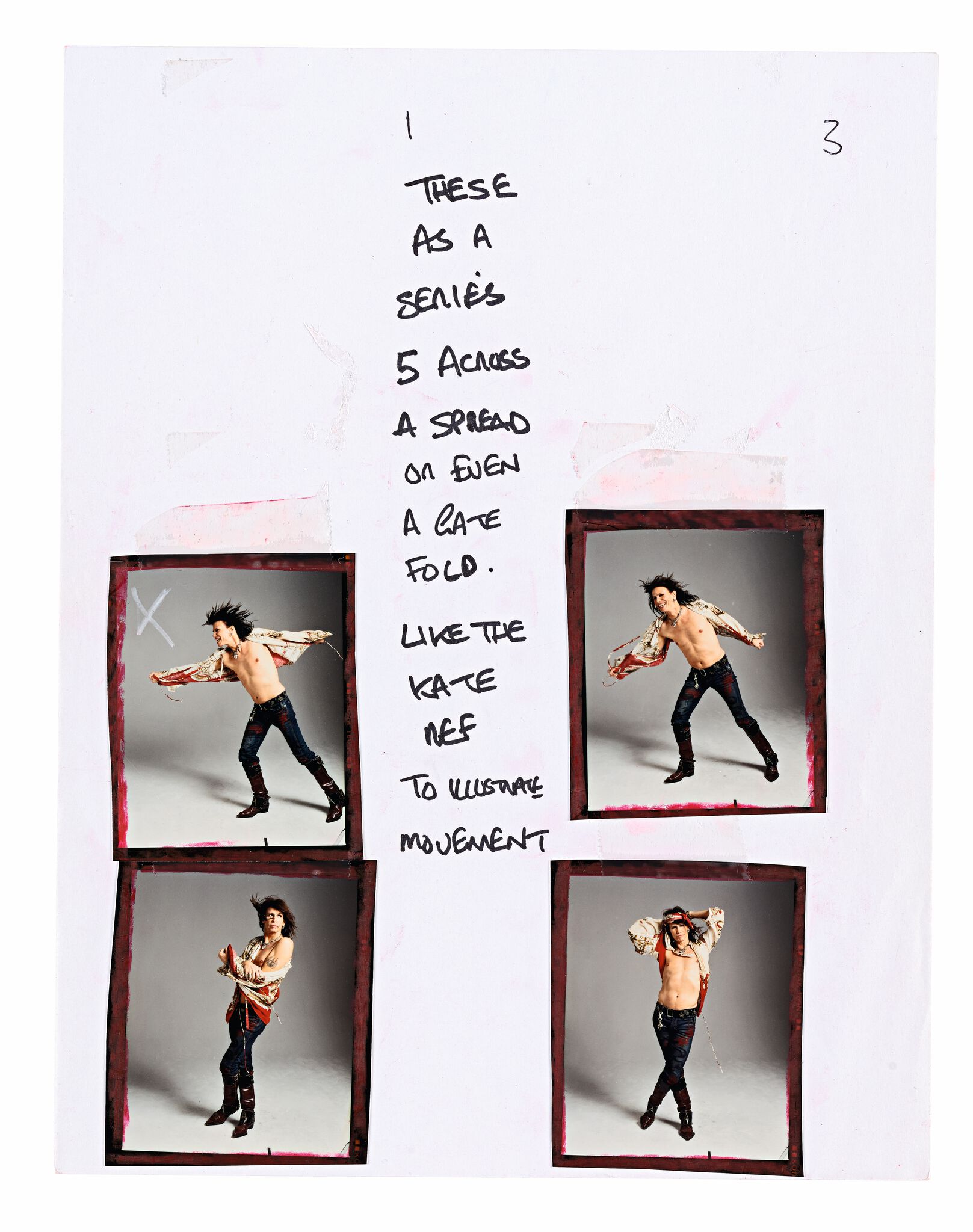

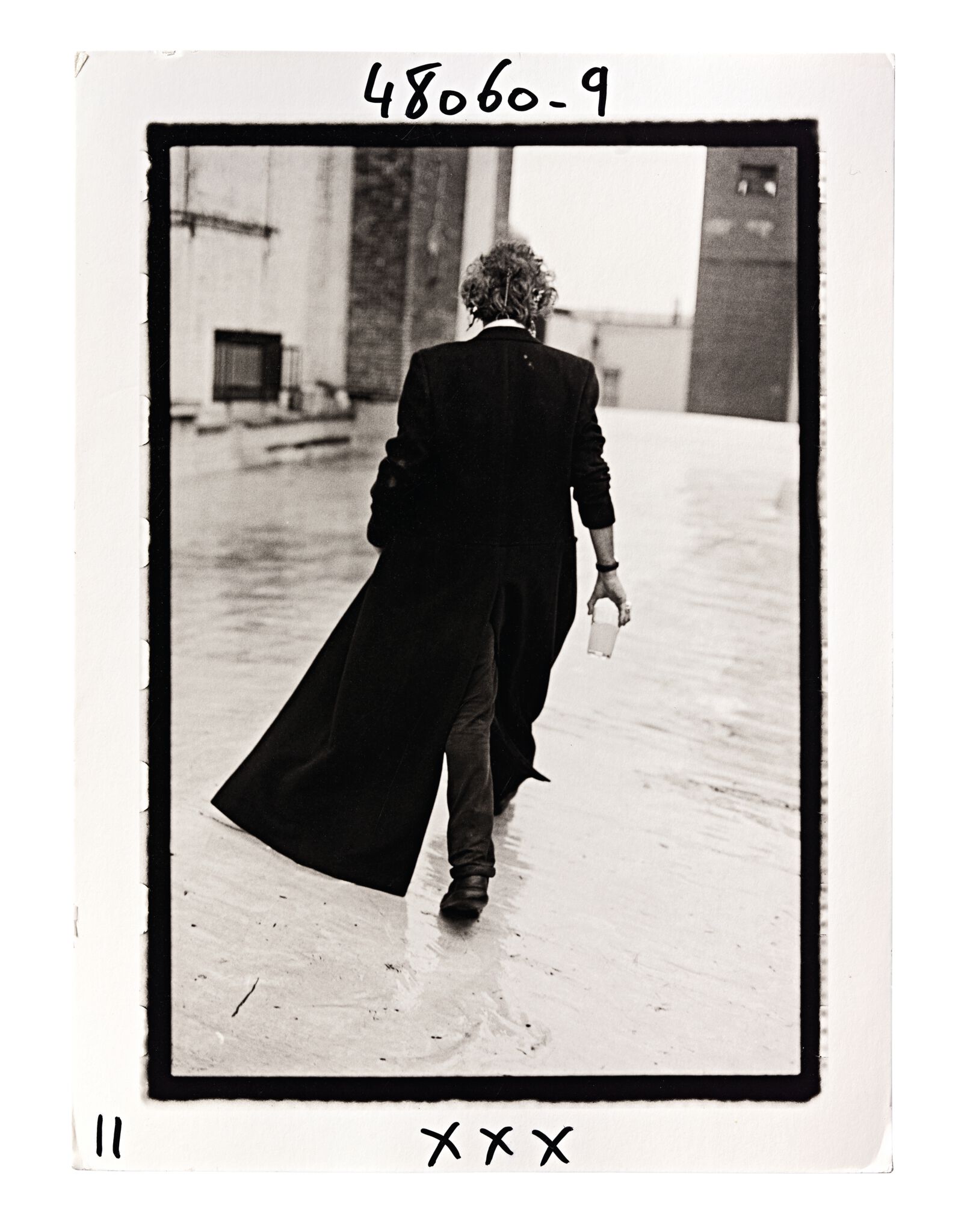

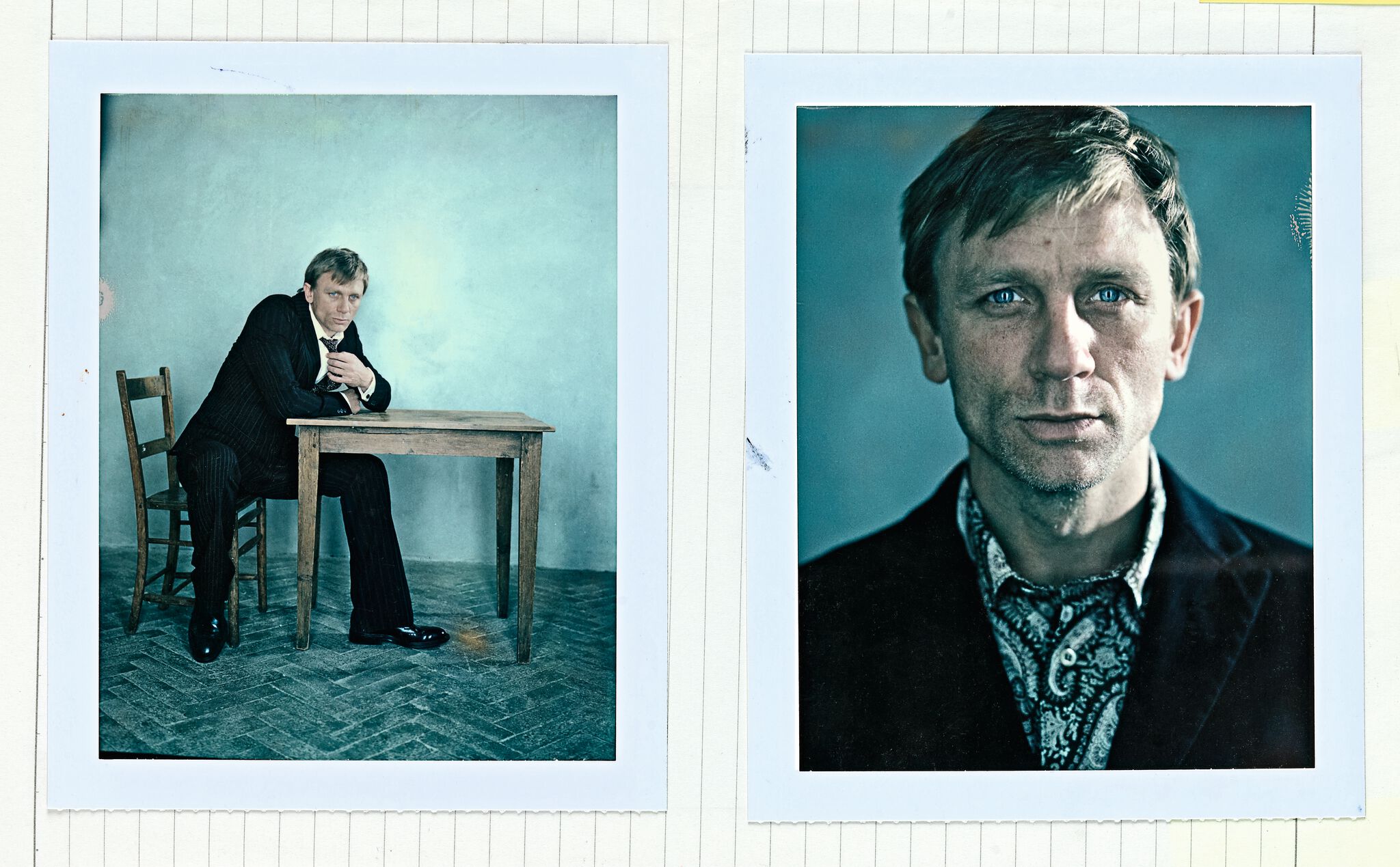

Absolutely by mistake. It was very funny. I was clearing out our garage in London and came across a box. And I opened it and saw literally over thirty years of Polaroids that I had kept from all the shoots across my career. It was extraordinary. And because they’d been in a box, everything was preserved beautifully. Then I found my notebooks, which I had always used prior to and during every shoot as a guide and record of the story we were creating. I mentioned the box to Catharine Snow, publisher at Clearview Books in London. She looked at the Polaroids and said, “Jo, there’s a book.” And she came up with the wonderful title, The Power of the Polaroid.

Why are Polaroids so special?

What’s fascinating is that every photographer that I’ve worked with has their own relationship with Polaroids, and that was so interesting, because some used them for light, others for composition. Some used them as a storyboard to just keep the idea going. And sometimes, for example, if we took a Polaroid, we would say, “This is actually capturing the moment.” And this was quite often the image that we would select. The photographer would then peel the back off the Polaroid, the negative, and develop that. The Polaroid is the original moment.

Do you miss Polaroids today?

Yes. I miss being able to play around with the printed images and physically laying them out on a table, because they chart the development of a story and whether or not our processes are achieving what we set out to achieve.

You were against using your notes and mood boards for the book, right?

I did my little doodles and my mood boards for me, for no one else. That was the hardest thing for me, to allow that. But because the designers of the book, Michael Nash Associates, are so brilliant and I trusted them, I had to let go.

Did you start making notebooks at the beginning of your career?

Yes, I did start creating scrapbooks and notebooks at the very beginning. It takes years to learn and hone your craft. And I worked with lots of photographers, but they never managed to capture what I wanted. It wasn’t until I worked with the Douglas Brothers that the magic happened, and I thought, “Oh, I’m not crazy. I can realize what is in my imagination.” That’s why I decided to start the book with the Douglas Brothers, because that shoot was the key to a visual door which had been opened properly for the first time.

You experienced the golden era of magazines. What was the most wonderful thing about that time?

It really was a golden age, and it was full of the most talent. And talent is sexy. There was a fizz in the air. You could feel it; this was the eighties. I recall my first day at Vogue, I started in women’s wear, and I remember looking up at Vogue House and thinking, “Vogue, here I come.” And I ran up the stairs, I was so excited, because here I was starting a career which I hoped would take me to the top.

Where did you start exactly?

I started as an intern, making tea and coffee. Although in those days, you weren’t called an “intern”. You were called a “rover” at Vogue, which meant you moved around from department to department, and you really learned how a magazine worked. I remember being thrown to the art department and there was a wonderful art director called Barney Wan who was just extraordinary. And of course there were no computers. There was this glue called Cow Gum that you used to paste all the art, all the layout. And I’ll never forget watching Barney take the photograph and pictures, and they suddenly dropped on the floor. And we looked. And the way the pictures fell on the floor, that was the layout for the magazine. And so, you were able to make mistakes and learn from that. I used to work with a photographer called Terence Donovan. He was a great photographer. And he said to me, “The computer, Jo, it’s going to kill it. It’s going to kill magazines.”

How so?

Because everything is cookie-cutter, everything has the same format. And you’re looking at a screen. But when I started out, you immersed yourself in the layout. You just played with letters, sizes and graphics. It was a very magical, creative time. And just watching the photographs being retouched by these extraordinary artists! They retouched the photographs with paint; it wasn’t done on a computer.

Allow me to ask you this: Would you describe yourself as a technophobe?

There’s wonderful things behind this tech revolution. It’s very clear it is essential to modern living. However, I do worry when I see so many people walking around that they’re not looking at their surroundings properly. They’ve got their eyes down on their phones or are taking selfies. Their world is the tiny black screen on their phone. I feel that is numbing all our senses, because no one is absorbing things. But that’s only my view.

Did creativity have a different meaning than today?

No. I think there’ll always be lots of amazing creative people. And there’ll always be people that think outside the box. People that are curious and enthusiastic. In the book, there’s an interview with David LaChapelle, who started out at the age of seventeen. When he picked up a camera, he said, he spent the first five years in the darkroom learning how to print black and white. And then it took another five years to learn how to print color. And before he started to earn his money, he took pictures of weddings. He says that picking up a phone and taking a picture with it is not photography. I think that with anything, whatever it is, you have to really work at it and learn. And you never stop.

What makes the difference between a good photographer and an excellent photographer?

I think it’s what touches you. If a photographer can harness your imagination, then I think that makes him great. It could be a fleeting moment, it could be so many things. I think what’s very interesting with all the photographers that I’ve worked with is that I’ve always learned something from them. I remember working with Connie and Russell, two photographers who operate as the internationally acclaimed Guzman. Connie would choose one of the pictures, and I would say, “That image looks awkward.” And she would reply, “But awkward is good.” The picture I always chose in the end was her picture. Or Russell would suddenly pick something which we hadn’t even thought of before. I suppose it’s rather similar to hearing a piece of music written by a brilliant musician. A few chords in, and the impact of the notes is so extraordinary, yet you don’t know why.

You’ve known a lot of famous people. Do you recognize a real star at first sight?

Yes, I do. I can recognize a real star because they generally come across as comfortable in their own skin.

Can you give us an example?

I was working on a portfolio with Peter Lindbergh and I wanted to photograph the great actors in Hollywood who were over seventy. This included Kirk Douglas, Tony Curtis and Sir John Mills because there’s something magnificent about these men. We went to set up the shoot at Kirk Douglas’s house. As I was helping Kirk down the stairs, I remember thinking to myself, “I’m holding on to Spartacus.” Do you know the film?

Of course. That must have been a very moving moment.

It was. And it was the first time I ever saw Peter look nervous.

And Kirk Douglas?

His personality filled the room. And it was magnificent. He sat down, Peter clicked his camera three times and said, “I’ve got it. That’s it.”

Only three times?

Yes. He said, “I’ve got it.” Because Kirk Douglas was Kirk Douglas. As I mentioned previously, the real stars are always comfortable in their own skin.

In your book, you tell the story of William Claxton and his photos of Steve McQueen. Can you give us a brief synopsis here?

The story begins when I was in women’s wear. I used to go to the Les Deux Magots café in Paris and to Café Flore, and there was this little postcard shop there. I always bought these amazing black-and-white postcards of musicians like Chet Baker, and I was aware that the photographer was William Claxton. There was something magical about those photos. And when I moved into men’s wear, I remember the first men’s wear shows and jazz was being played down the runway. And I thought, it would be lovely to replicate some of those William Claxton postcards. But then I thought, “No, I don’t agree with plagiarism.” So I did some research and got his phone number and one night, I plucked up the courage to call him and said, “My name is Jo and I work at GQ, and I’m a huge fan of yours and I would love to do a set of pictures with you photographing real jazz musicians. And he said to me, “Oh my goodness. I would love to do this with you. I’ve been waiting for someone to call me for years.” I was thrilled.

It is indeed. What happened then?

I then flew to America, and we photographed all these extraordinary, amazing jazz musicians for GQ. And then I organized an exhibition for him in London and was later invited to dinner by him and his wife, the wonderful Peggy Moffitt. During dinner I asked him, “Who else did you enjoy photographing?” And he said, “Steve.” And I asked, “Steve who?” His reply: “Steve McQueen.” I asked where his pictures were and he said, “Ah, well, you know, they’re in a dusty box somewhere.” He brought out the box, I looked at the photos and said, “William, this is unbelievable. You’re going to do a book.”

And you spotted the TAG Heuer in one of the photos?

Yes, in one of the pictures, I saw Steve McQueen with a TAG Heuer watch. They were a big advertiser for Condé Nast. So I said to my publisher, “I’ve got an idea. I’ll organize an exhibition. Let’s get TAG Heuer to sponsor it.” And of course, it was sold out and the exhibition became a kind of tour around the world. And that was how the relationship continued and we ended up taking the most fabulous pictures.

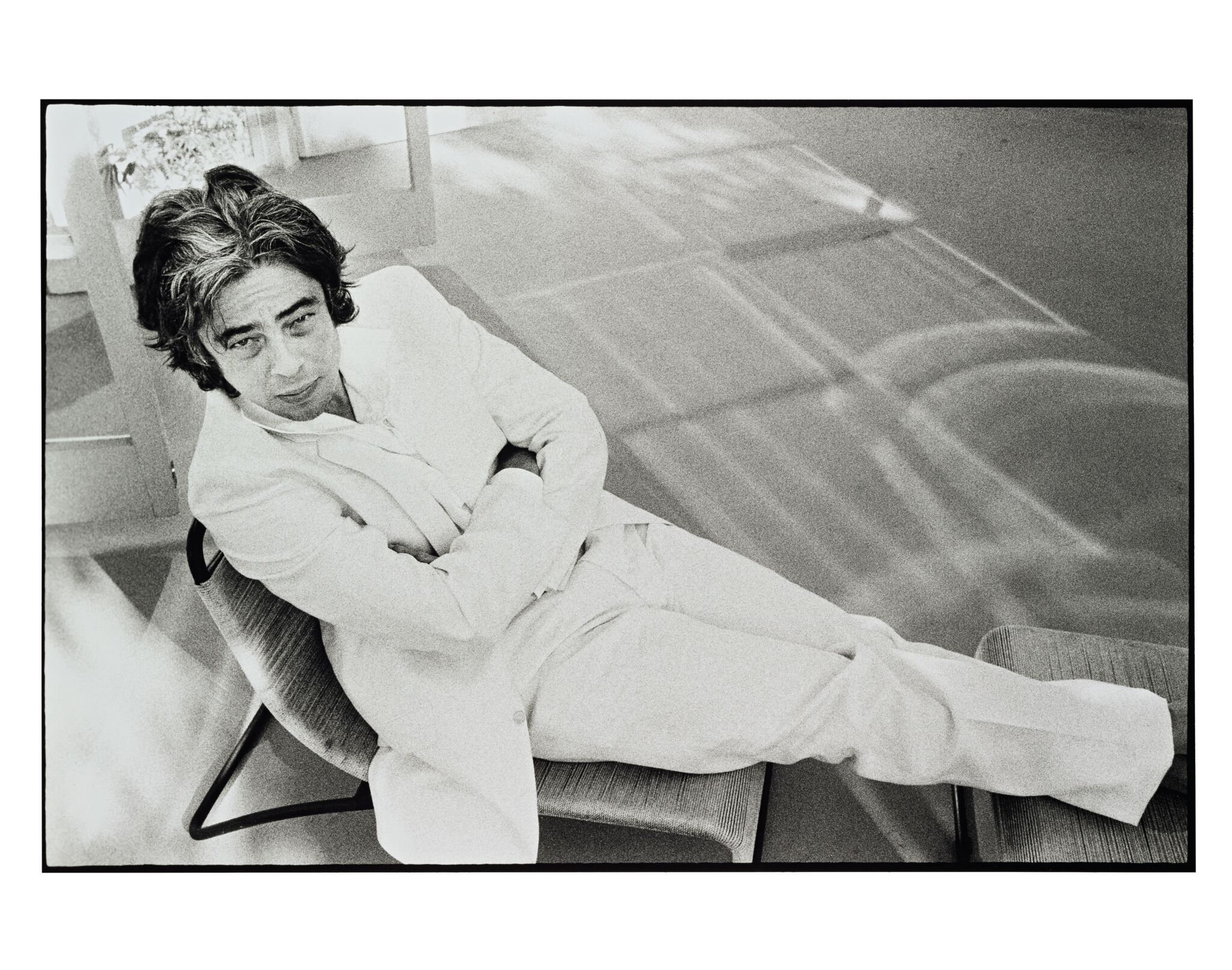

William Claxton also photographed Benicio del Toro, didn’t he?

I met Benicio del Toro at the GQ Men of the Year Awards in London. He was sitting next to me at the table and had just got the Oscar for the film Traffic. He and I started talking, and as it turned out, he loved photography. I said, “Are you familiar with the photographer William Claxton?” He answered: “He’s my hero.” I said, “Well, he’s a friend of mine.” So I said, “I have an idea. Let’s get William to do a shoot with you using the same film he shot Steve McQueen.” And he said, “Done.” It was such a fantastic shoot. William, who died in 2008, was honestly the kindest, sweetest man, an amazing photographer. And we did lots of lovely stories together. He was wonderful.

We can’t talk to you without talking about fashion. What is fashion to you?

It’s a cycle. What goes around, comes around. Skirts go down, skirts go up. Because they can only go so far. Right now, all the long skirts are creeping up. Fashion reinvents itself all the time but essentially stays the same.

And what about style?

Style is the most interesting thing because style is when you are completely at one with yourself and you’re comfortable. And if you’re comfortable under your skin, you can wear anything and look good. That, to me, is style. If you’re always aware of what you’re wearing, it looks ridiculous.

And are there any style essentials for men or women?

I think so. For a man, I think it’s about having the right basic pieces in the wardrobe for every occasion, such as a good suit, a good coat, a well-cut jacket and a crisp white shirt. A classic tie and good quality shoes are always noticeable. And then you can build on that.

Let’s talk about taking pictures of men and women. What’s the difference?

For me, it’s very important, whether I’m working with men or women, to ensure they are comfortable and relaxed. A general rule for women is to build more time into the schedule for hair, makeup and clothes fittings, but apart from that it really depends on who it is you’re photographing.

One last question: Why didn’t you become a photographer?

When I began my career in the fashion industry, what I knew was Vogue – which was promoting fashion, not photography. Even though photography is intrinsic to the process of making a beautiful picture, I wasn’t aware that this was a career option. Fashion and clothes were, so that is the direction I took. Later on, as I began to work with photographers, they and I realized that I probably did have the right eye for the medium, but by then I was deeply involved in the more collaborative process of fashion styling. I adored the teams I put together and the management of the shoots I set up, and that was my world. I took pictures for personal enjoyment. but it never occurred to me that I could pursue photography full time. As it is, I am lucky enough to work with photographers who can realize the dreams that are in my head.

rampstyle #26

Two thin ovals far up inside a circle, a curved arc below, sketched on sunny yellow. In a split second, our brain has combined the elements into a smiling face, instantly putting us in a good mood. Wonderful! A smiley like that just feels good.

The smiley was invented twice: once in 1963 by Harvey Ball, a graphic designer and advertising expert, who was commissioned by a U.S. insurance company to create something to motivate its employees. The company paid $45 for it, but Ball never had the idea of applying for trademark protection. Franklin Loufrani, a French management consultant, was more enterprising. He placed his smiley in the newspaper »France Soir« in 1972 as an indication of good news and had it legally protected. So much for the first round of inventions. We owe the second invention to Scott Fahlman. The professor of computer science wrote on the Carnegie Mellon University electronic discussion forum on September 19, 1982: »“I propose the following character sequence for joke markers: :-). Read it sideways.« It was probably the ten silliest minutes of his life, Scott Fahlman revealed extremely gleefully in conversation. So let’s take note right here: Just ten minutes of silliness can make the world a happier place.

With this in mind, we wish you a lot of fun!

Interview: Michael Köckritz for ramp

Photos: © The Power of the Polaroid: Instantly Forever by Jo Hambro