A Land Rover Series I 86 with an eventful history comes to London to meet its latest and last legitimate offshoot, the Defender Heritage. Want to know how to honor tradition and celebrate past virtues? Here’s how.

There’s the paint, the famous Deep Bronze Green (also known as Ascot Green), and beneath that, where sixty years of weather and use have thinned it out like a battered Matchbox car, there’s nothing – no primer, just bare Birmabright, the typical Land Rover alloy of aluminum, magnesium and manganese from Birmingham, where it was produced mainly for aircraft construction during World War II. Unlike other aluminum alloys, such as Duralumin, Birmabright does not harden with age and is particularly resistant to seawater corrosion. The alloy is rather unsuitable for machine fabrication, however, so automotive engineer Maurice Wilks looked at body styles that could be easily cut and formed by hand. Steel was not available, and existing quotas were allocated to established companies that exported abroad. This was the situation when Land Rover launched its first series, based on the chassis of the reliable Willys Jeep, of which there were many cruising around the British countryside at the time.

The 86 model, built starting in 1953, freed itself from the American platform with the now-famous ladder frame, welded together from strips of sheet metal, and a wheelbase extended, as the name implies, to 86 inches. Our model was delivered to Australia in 1955 – CKD, which stands for “completely knocked down”. Good thing Land Rover had a subsidiary in Sydney that assembled all the parts according to factory specifications.

The buyer (and father of the current owner) was F. B. Burton, who left us a prominent message here on the right fender: “Mount Gilead Jindabyne”. That’s an area in southern New South Wales, in the Snowy Mountains, 460 kilometers from Sydney. Gilead was a fertile wheat-growing plain of biblical times, and our Mount Gilead here is also a prosperous land with a special place in local history. The Series I 86 was a workhorse – dependable, original, undeterred, a farmer’s friend, as they called it in those days. Though first you had to shoo away the kids who were constantly playing on and in it. What a fantastic robber’s den it made underneath the canvas top! “We did everything in the Old Green Girl,” says Burton Jr. “We’d go fishing, and there was a light rifle clamped across the front beneath the windshield in case Dad saw a rabbit, which he’d unceremoniously pick off while driving.” As a memento, a .22 cartridge is mounted there today in place of the gun. “There was no heater,” the owner recounts, “we had to put on another layer of clothes. My sister and I sat in the back with the dogs, our little brother up front between dad and mum. It’s got three seats in the front, you know.” All the children were picked up from the maternity hospital in the Land Rover, and all three later learned to drive in it “thanks to a cushion to sit on”.

The workhorse became a member of the family. Of course, without sacrificing any of its utility and practicality that the makers had intended. The side windows and frame could be removed in one easy step, the radiator grille was often used as a barbecue over an open fire, and the backrests of the three front seats could be folded down in case it rained inside the uncovered car. That way you could keep the seat surfaces dry. The windshield could also be folded down, at least as long as there was no spare tire bolted to the front. Few other cars bring you in such close contact with the world around you.

The two-liter, four-cylinder engine only generated around 50 hp, but it was considered indestructible and ran on practically anything containing a flammable substance. Eighty octane was plenty. Unlike the successor models, the 86 still had a soft suspension. Its fuel tank was located under the driver’s seat on right-hand drive models, as was the case with later models as well, though the filler neck back then was found by simply folding up the seat and unscrewing the cap. A pull-out metal neck with strainer insert still makes filling easier today. There was an erratic fuel gauge floating inside the tank, and if you really wanted to know how much fuel you had left, that was the place to look, because the trembling fuel meter on the instrument panel tended to oscillate wildly from zero to full at any given time. After switching on the ignition, the first thing you hear is the typical whirring sound of the fuel pump filling the carburetor. A separate start button below the dashboard then calls the engine to life.

In an emergency, in case the battery failed, you could also start the car using the extra-long starting crank. “The odds of either getting the engine started or breaking your arm when the crank kicks back are about fifty-fifty,” as knowledgeable Brits explain with their typical deadpan humor. Three levers protrude from the floor panel: the regular H shifter (in earlier models, first and second gears were still unsynchronized, so they had to be engaged by double-clutching) and two off-road levers. Yellow engages the four-wheel drive (with the potential for disengaging your shoulder joint), while red selects low range to give you the torque you need for towing or climbing. When both levers are engaged, there’s really little that can stop the headlong advance of the stoic Land Rover. (“Go anywhere” was Land Rover’s first advertising slogan, by the way.)

Quirks are kept to a minimum. That’s because many of the details that seem to be a curiosity at first glance turn out to be quite practical on closer inspection. An especially practical feature is the modern-looking light switch, designed as a rotary knob around the ignition, as well as the two windshield wipers that can be operated independently of each other. The handbrake, by comparison, is fairly medieval. The lever engages a drum acting on the Cardan shaft directly behind the low-range gear in the center of the car. With four-wheel drive engaged, all four wheels are blocked; in rear-wheel drive mode, it’s only the rear axle. The strong braking effect is amazing; the car is downright anchored. Thanks to its secure position, the handbrake functions independently from the rest of the braking system and is relatively resistant to dirt. There’s no way to overestimate its practical, utilitarian value.

As a gallant escort in the big city, the Old Green Lady was accompanied by a 2015 Defender Heritage Edition – the last series, a farewell to the best friend of the horizons, the stylish trailblazer at the end of the road, the universally promising ladder frame vehicle with universal patent. With the unshakeable practicality of a workhorse, it upholds virtues that will no longer exist in this form. With the unconditional end of production for all classic Defender models, we mourn not only the end of unintentional beauty in automotive engineering, but also the end of direct mechanical action in cars.

The Land Rover Defender brings to an end the days when cars could be disassembled and reassembled in a desert tent. In this respect, the Heritage Edition was designed as a tribute to the Series I, classically reduced with a white roof, headlight trim in body color and painted wheel arches. In reference to the license plate of the first Defender (HUE 166), the Heritage Edition bears small “HUE 166” logos on the left fender and on the seats.

The center console in body color is classically beautiful, like a short-wave transistor radio, unfortunately not made of sheet metal, though it looks like it. Clear main instrument panel and an analog clock in dead center. An unexpected kinship to Porsche: the ignition switch is located on the left side of the steering wheel column. (An heirloom of right-hand drive.) Three levers still protrude from the car’s floor with the same gearshift scheme, behind them the massive lever for the handbrake.

We’re not talking about perfection here, but about logic. A small example: The light switch is designed in such a way that it protrudes just in front of the ignition key when in the “on” position. So if you want to turn off the engine, you first have to pass the light lever and will be sure to remember to switch the headlights off as well. Ingeniously simple, simply ingenious.

A familiar feature for decades is the seating position: upright, but close to the door. There are only a few centimeters of space between the steering wheel and the side window. People like to drive with the window open in summer.

The bright Grasmere Green of the early years, the solid dark green steel rims embedded inside the reliable Goodyear Wrangler tires, the radiator grille (plastic, unfortunately, so no good for barbecuing), the light-colored roof with panoramic windows, the spare tire carried piggyback, all of it seems down-to-earth, sincere, unpretentious. And now that the classic Land Rover has reached the end of the road, it will be particularly prized. A big thumbs up from all the plastic tubs on wheels that are cruising around our streets these days.

When it comes to engine, drive shafts and wheels, they’re still as noisy as always, with even more sound capable from the built-in radio. Though when everything else is so unfiltered and raw, a soft accessory like seat heating is a welcome treat.

Clutch and steering require effort – and in the city that means a powerful workout as usual. On the highway, you might make it up to 140 km/h before you give up. But please, no misunderstandings! Driving and operating this car is an enormous pleasure, you enter a state of mastery, with the result that an intimate relationship is established with the car, as a reference point that all other vehicles must compete with – in vain.

In this respect, the Defender is a worthy successor to the Old Green Lady, to which we have summarily promoted the old girl. She’s the real eye-catcher here in the city, rust-free through and through in her original condition and in the best of health thanks to the dry Australian climate in which she has lived all her life. But the family summers on the Norfolk coast will also be good for her – that much prophecy is allowed.

Text: David Staretz

Photos: Amy Shore

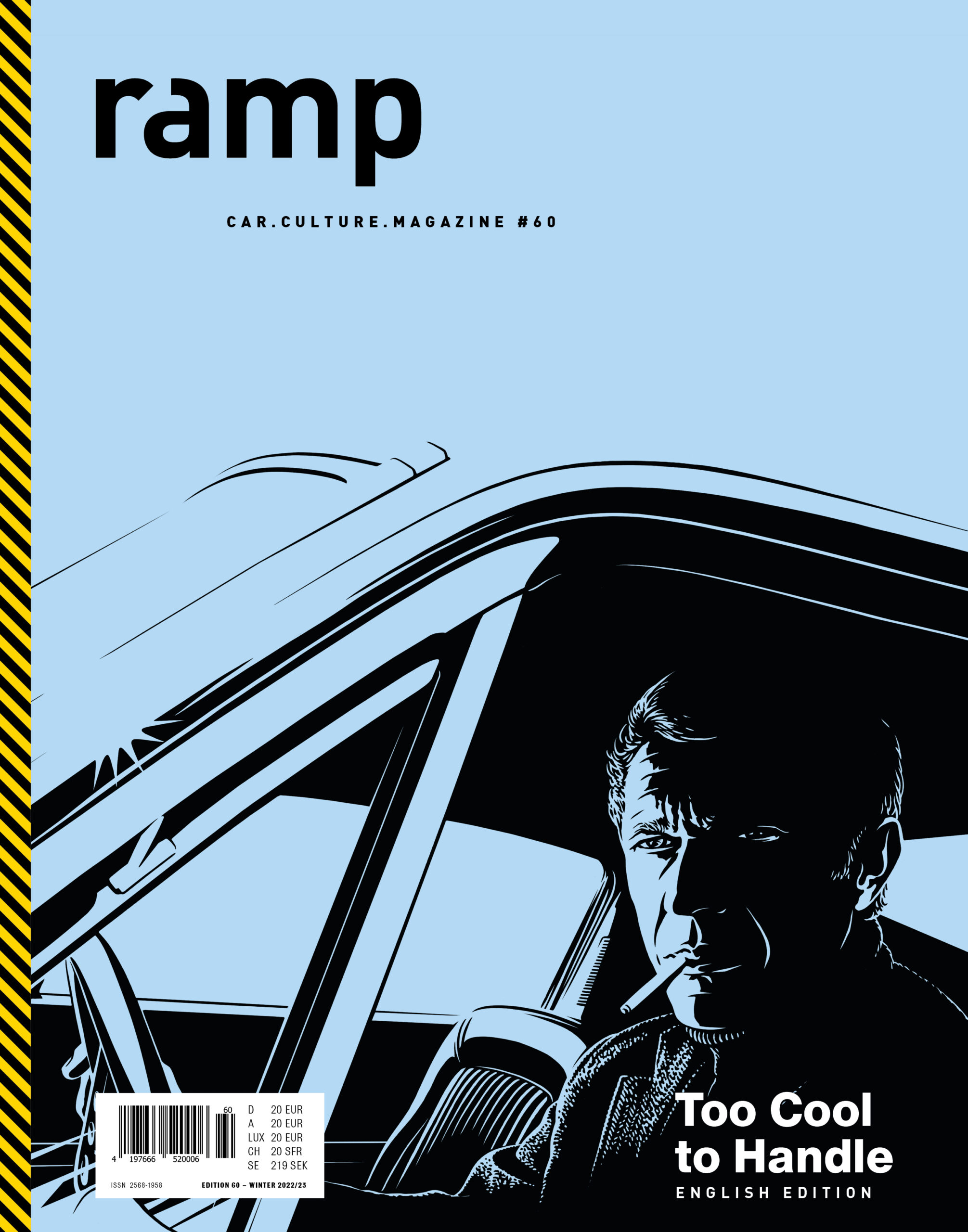

ramp #60 – Too Cool to Handle

As a high-impact multimedia brand that takes an all-encompassing, end-to-end approach to publishing, ramp is an absolutely authentic expression of quality, integrity and excellence. Its trailblazing luxury magazines, recognized with numerous awards over the past 15 years, have been celebrated for their cool and unconventional, not to mention inspiring and pioneering style, since day one.

ramp, the lavish and beautifully designed coffee table magazine, celebrates the enthusiasm for cars and driving in a passionately subjective, personalized fashion.

Immediate, authentic, intense. Fresh perspectives, avant-garde

A magazine about coolness? Among other things. But one thing at a time. First of all, it’s off to the movies. There’s this businessman from Boston who helps relieve a bank of a substantial amount of money. The insurance companies are on to him, but they can’t prove a thing. That, in a nutshell, is the plot of the film classic in which Steve McQueen plays Thomas Crown, who remains a mystery to the viewer throughout the entire film and who the actor plays with incredible composure, exuding absolute coolness at every moment. The German title of the film – Thomas Crown ist nicht zu fassen – hides a wonderful play on words, by the way. It could mean: Thomas Crown is unbelievable. Or it could mean: Thomas Crown cannot be caught. Cannot be seized. Cannot be grasped hold of. He’s just too cool to handle. Much in the same way, coolness also eludes our attempts to grasp it. A fundamental vagueness shrouds this fascinating phenomenon of longing and desire.

We’re fascinated by the irrational, the incomprehensible, the unbelievable. That’s why we also enjoy breaking the rules. We are living contradictions, as neuroscientists and psychologists so dryly explain. Our irrationality, innovation research tells us, is the secret to our creativity. It is our irrationality which insists that it is not we who must adapt to the world, but that it is the world that must adapt to us. This is another reason why any kind of progress depends to a large extent on our irrationality.

“If people never did silly things, nothing intelligent would ever get done,” the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once so aptly said. The physicist Richard Feynman opens our eyes to another aspect in this regard: “Physics is like sex,” he explains. “Sure, it may give some practical results, but that’s not why we do it.” And that’s just about how it was with this issue of ramp. Sort of.

With this in mind, enjoy!