A super super super test in Vienna with two flashy cars that nobody seemed to be interested in. In search of what makes this city so special, with an exploration of the typically Viennese aspects of black humor, the people’s general sense of melancholy and their habit of incessantly complaining about everyone and everything every chance they get.

Of course, there was no answer to be found – or at least only a very Viennese one.

“Grüß Gott, welcome and don’t think for a moment you’re in Germany, because appearances are deceptive,” my friend in Vienna said to me during my first visit many years ago. “They may speak German here, but the language is completely different from what you’re used to. So don’t trust your ears, even if you think you can understand what’s being said.” And with that, he pressed an Austrian-German dictionary into my hand. The dictionary showed me that they have lots of different words for things in Austria. Simple things like chair or refrigerator or horseradish have completely different names, for example, and a coffin is referred to as a “wooden pajama”. I quickly committed most of the useful Austrian terminology to memory – the dictionary wasn’t particularly thick – but I still had some communication problems when talking to the locals. These communication problems had nothing to do with the vocabulary, however. Austrians are complicated, they often don’t say what they mean and don’t mean what they say. And when they greet you warmly and politely, you still can’t be sure if it’s coming from the heart or if it’s the famous Viennese Schmäh, a blend of compulsory charm and dark, wry humor. Whatever the case, the Viennese want to please. A common joke my Viennese friends told me was this: An ugly man is always seen accompanied by a beautiful woman – and nobody understands why. When asked how he does it, the ugly man replies: “You’ve got to make them feel welcome, greet them warmly when you see them.” The Viennese know how to greet people and make them feel welcome. There’s always a festive sort of mood in the city, a merry sense of chaos, as if the locals were getting ready for Carnival, it’s about to start, they just can’t decide which costume to wear yet.

When you’re out exploring the city, you can hardly tell the landmarks apart from the regular buildings. Everything in Vienna is an attraction, every person and every food stall, especially the Würstlstand. Almost every one of these sausage stands sells champagne in addition to sausages. Maybe someone will feel like drinking champagne in the snow while waiting for the tram to come, or so the Viennese seem to think, those show-offs! Their humor is particularly morbid, subtle, nuanced, with the ability to laugh at itself. Complaining is an art here, a part of everyday life. On every corner there’s a coffeehouse that looks like a theater, where people drink specialty coffees called Melange or Verlängerter and play cards in front of a stunning backdrop. Often, it’ll be located right next to a theater that looks like a coffeehouse. Many old friends and acquaintances of mine, German actors from Munich and Berlin, have moved to Vienna. And I understand why. Vienna is a paradise for theater people, because everything here is theater, everything seems unreal. Following the collapse of the great empire of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, the Austrians tried hard to shift their post-imperialist ambitions to the cultural and entertainment sector: They wanted to have the best opera in the world, the best philharmonic orchestra, the most magnificent opera ball and the best soccer team in Europe.

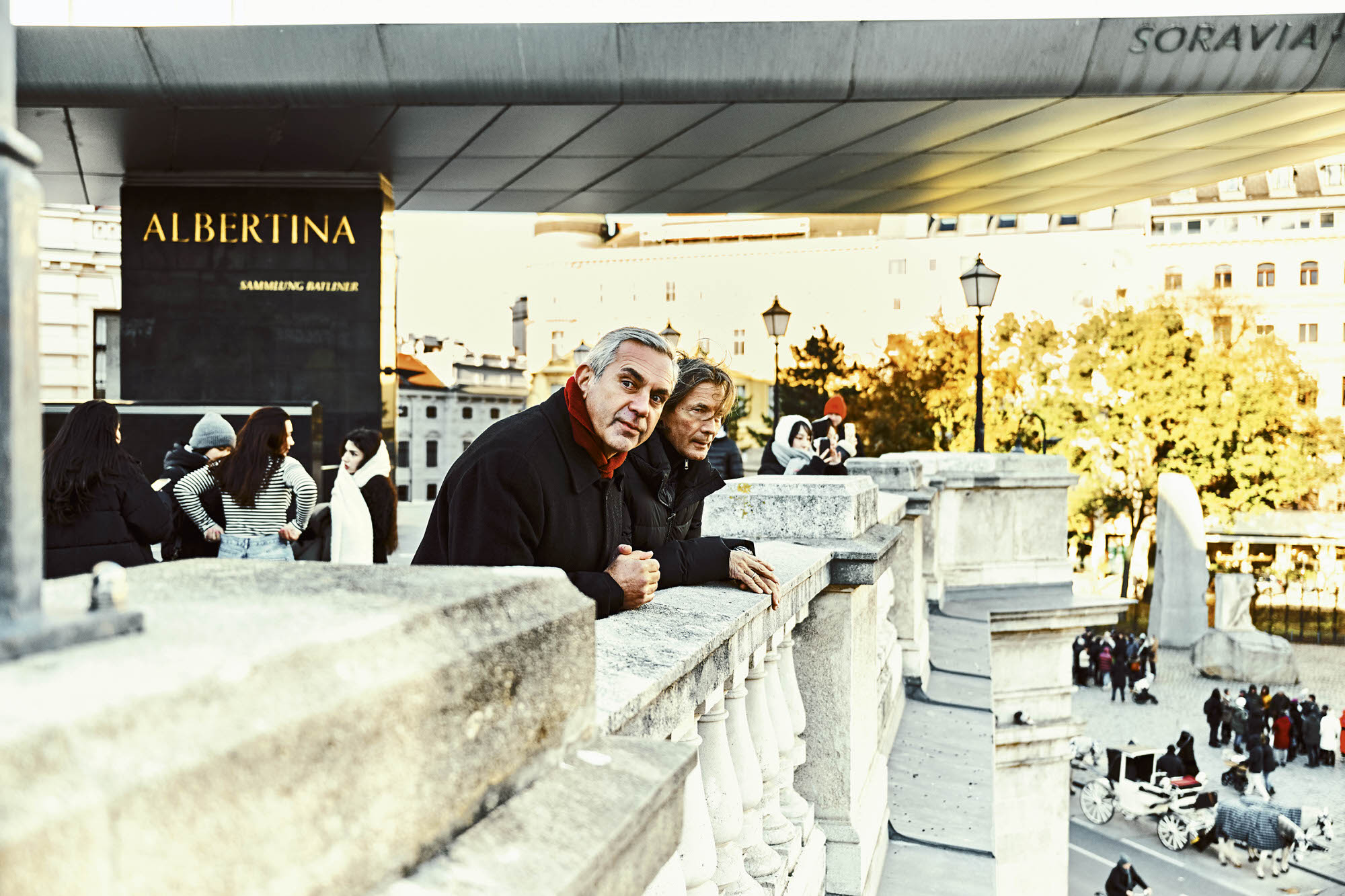

They were quite successful in their endeavors, with the possible exception of soccer. And so two Austrias have emerged, leading a peaceful coexistence. One is a charming little country on the European landscape, a sausage in the middle of Europe, with vineyards and a strong social market economy, ranked eleventh in terms of gross domestic product. The other Austria is big and mighty, the cradle of good taste and fine cuisine, setting the tone for the rest of the planet. This second Austria is where most of its inhabitants find their true home. For a long time, we have dreamed of conducting our super super super test abroad with Michael, the editor-in-chief of the best automobile magazine in the world. We don’t just test cars, after all, we test ourselves. Year after year, we explore the question of whether there is a place for luxury in this shaky, shimmering world and what a person really needs to lead a fulfilling, exciting life.

What puts us off, what makes us happy – and why? Vienna is a great place to think about all this, a place where swarms of tourists from all over the world come to admire the beauty and the elegance of a bygone empire, constantly snapping selfies with horses and lining up in the cold at the sausage stand to get their hands on a frankfurter served with champagne. Our decision was clear: Vienna here we come!

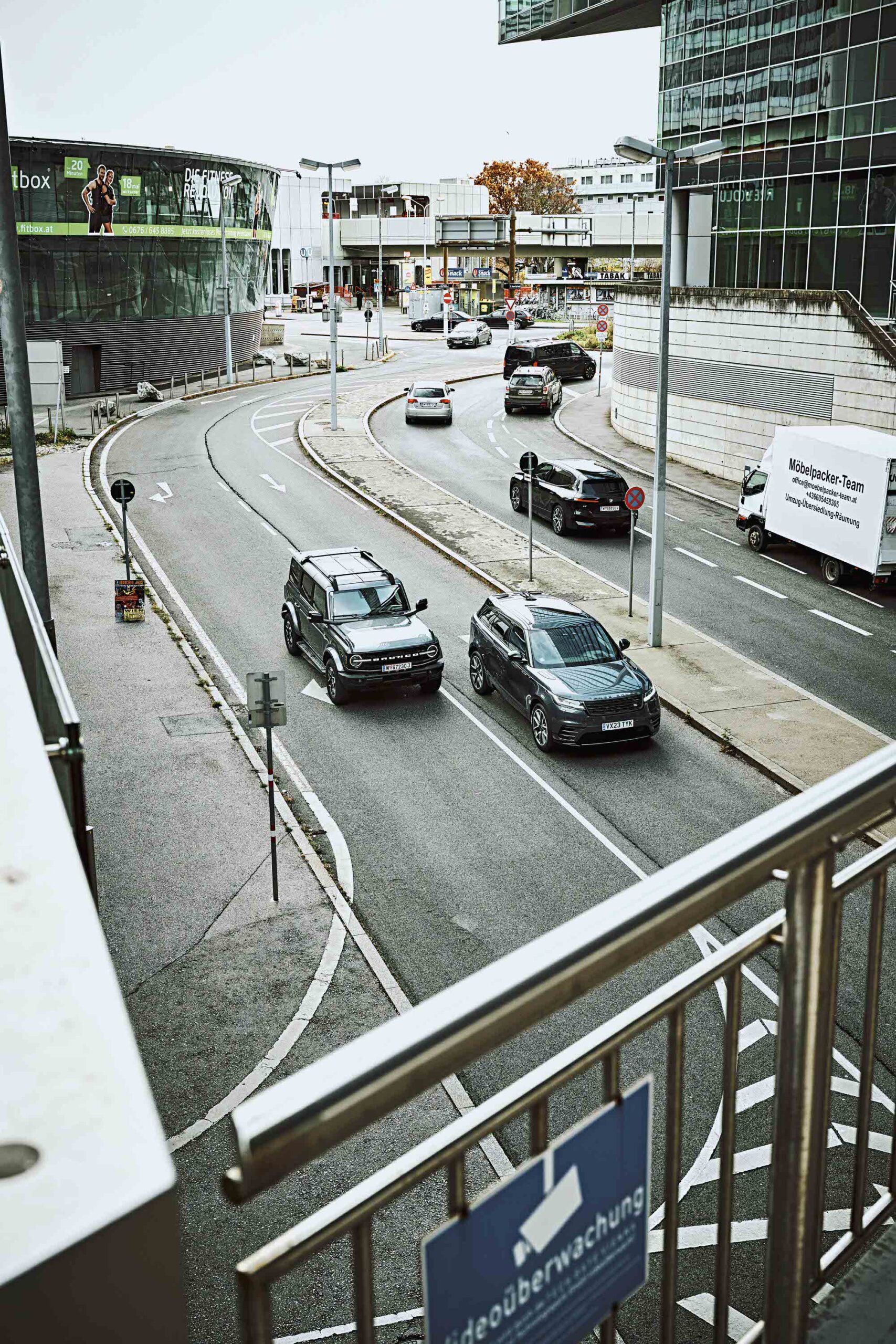

On our little tour of discovery, we were accompanied by two rare cars, a Ford Bronco and a Range Rover, one American and one British. Big, powerful automobiles that would stand out in any city. But not in Vienna. During the Cold War, Vienna was a hotbed of international espionage. The British, the Americans and the Russians all played their underhand games here, engaging in secret coffeehouse diplomacy, right up until socialism collapsed under its own weight and its spies had to learn how to become businessmen. Though not all of them, unfortunately, and one of them later became president of Russia. I don’t think the spies back then drove flashy cars like ours, but you can’t impress the Viennese with cars anyway; they’ve seen it all before. I did have the feeling that our cars were spying on us, however. Though we had nothing to hide; our objectives were completely transparent. We wanted to understand the magic of this city. More than once, Vienna has been voted the most livable city in the world, despite the fact that the Viennese are constantly complaining about their hometown. Obviously, the one thing doesn’t exclude the other. Being happy and dissatisfied at the same time, how does something like that work? And who got to vote on this in the first place? Did they ask the Chinese tourists or perhaps the former Russian spies who stayed on? Indeed, you can hear Russian in Vienna almost everywhere you turn. No sooner had I arrived at our hotel than a mustachioed compatriot of mine asked at the reception if he could pay his four-figure bill in cash. The receptionist was not at all surprised and answered that of course he could. Anything is possible in Vienna. We had arranged to meet some local friends – Franz Sauer, David Staretz and Kurt Molzer, authors and journalists who are well acquainted with the Viennese philosophy of life – for a private chat at a small American bar in the 1st district. We wanted our friends to explain to us what is unique about Vienna and the Austrian way of life. The American Bar – that’s not only a description, that’s also its name – is a typical Viennese venue, an inconspicuous little landmark. Locals as well as architecture-savvy tourists know it as the Loos Bar. It’s one of the few buildings in Vienna designed by the famous Austrian architect Adolf Loos. Loos was an exceptional architect, imbued with a solitary, quirky personality, a womanizer, a difficult figure.

He spent most of his life criticizing his contemporaries, without exception considering all his colleagues to be washouts, his clients to be lacking in taste, castigating the conservative mores of his time and declaring war on any kind of ornament. He frustrated his clients, squandered enormous sums of money on megalomaniacal building projects, racked up horrendous debt and never repaid it. Reeducating the world cost him a lot of strength and energy and more than once landed him in extreme financial difficulties, and yet he remained one of the most sought-after architects and interior designers of his time. I once read some of his correspondence with clients. His letters were like declarations of war, angry attacks on a world ruled by poor taste. “You want your money back,” Loos wrote to a client, “and you think I owe it to you? The bitter truth is that you owe me! The whole world owes me, every single resident of this city, because without me Vienna would have long since fallen victim to kitsch and bad taste. Think about that!” In his most famous essay, “Ornament and Crime”, Loos criticizes all kinds of ornament as a sign of a cultural malaise. In his view, decorative elements on buildings should be an embarrassment to modern man. According to Loos, the artistic excess of the past was a dead end with no further evolutionary potential, making all ornament superfluous, even backward. “The man of our own times, who follows his innermost urgings to smear the walls with erotic symbols, is a criminal or a degenerate,” Loos said more than a hundred years ago. The American Bar, one of his most successful projects, was furnished in typical Loos style: practical, square, solid, like our Ford Bronco, only with more charm. The mirrors on the walls and on the ceiling make the small, cozy room seem infinitely larger; you have the feeling of sitting in a huge palace with a hundred people and a generously proportioned, extremely long counter. In truth, the bar is no bigger than my kitchen, it can barely fit a dozen people. It is an illusion, a mirage, a perfect cognitive distortion of reality. Nothing here is real, everything is fake, except perhaps the drinks, typical Vienna, typical Austria, typical Loos. We were able to park our cars directly out in front without any problems, quite unusual in Vienna. The cars’ sleek austerity made them a good match for the bar; they could easily have been designed by Adolf Loos himself. Our friends were already there waiting for us. Hello, grüß Gott . . . Well, would you look at that!

The first thing our Viennese friends complained about at the bar was that it was too loud, too crowded and that there were too many people talking too much nonsense. This despite the fact that there were hardly any patrons in the place apart from us. But it’s good manners here to complain. The Viennese are always careful to maintain the right balance of wit and melancholy. “You’re misreading the Viennese language,” they told us. “When we say, ‘Would you look at that!’, that’s not a sign of admiration, but of contempt,” Kurt said. The Viennese say this as a tongue-in-cheek way of expressing an insult, like “Who do you think you are? What rock did you crawl out from under? Would you look at that!” “Not at all,” David disagreed, “‘Would you look at that!’ is a mixture of curiosity and amazement.” “Actually,” Franz countered, “it’s about the pleasure of being surprised.” “No, it’s simply meant ironically,” added Kurt. “It’s just that people often overestimate Viennese irony. When the Viennese say something ironic, they don’t even mean it to be ironic at all. The Viennese aren’t actually all that cosmopolitan and open-minded, they just pretend to be. I’m totally fed up with this city, and when my daughter finishes school we’re going to leave the city and move to the countryside,” he said, adding: “There have always been a lot of foreigners here, for centuries, in fact. We were the capital of the Habsburg Empire after all, so xenophobia has become almost synonymous with tolerance here. The Yugoslavs and the Turks who came as working migrants in the twentieth century quickly became Viennese and today are the ones who rail most vehemently against the new foreigners and recent arrivals.” The Viennese always need someone to blame for something.

As the humorist and actor Helmut Qualtinger once said, ninety-nine percent of the city is inhabited by Viennese, the rest are people, and the city has always been much more cultured than its residents.

“Vienna has a long and exciting history. It’s older than its inhabitants and has seen and experienced so much more. There’s no denying a certain discrepancy between the city and its residents. You complain about the people here, but as soon as you leave, you miss them,” said Franz. “Not me,” Kurt replied. “The Viennese are individualists. A typical Viennese, sitting alone in the coffeehouse with his Melange . . . you can be sure that no one will be joining him.” Michael and I couldn’t make heads or tails of this conversation. Our Viennese friends seemed to have very different opinions about the nature of their city and the peculiarities of the Austrian language.

“If you ask me,” Michael chimed in, “I really like Vienna, it’s like a little Paris. Young people come here from all over the world to study, not to mention all the art lovers and spies. Vienna is a city that exudes youth and freedom, where everyone can do what they want. And that’s why I’m opening our next office here and not in Berlin.”

“You’re right, of course,” Franz agreed. “The geographical location is perfect. There’s always a wind blowing here, sometimes from the east and sometimes from the west, which is why it smells so good all the time here, it’s because of the breeze. And don’t forget that the city is surrounded by forests and hills, so it can’t keep endlessly growing like other European cities. Vienna will stay compact, the newcomers who come here quickly become Viennese, which means they keep to themselves. Vienna is where the Balkans begin, it’s a foundation of Western culture, it’s where all the winds meet, rubbing against each other and igniting a unique fireworks display of culture and the arts. Of course, the Viennese complain about their city as they always have, and some of them leave to swarm out into the big, wide world. But when the big, wide world becomes too big, Vienna is always there, waiting. The Viennese can always go back to sitting in the coffeehouse and complaining.” “If you ask me,” said Michael, clearly a fan, “I don’t find the Viennese all that grouchy. They’re a pretty cheerful bunch.” “Not at all!” our Viennese friends shout almost in unison. “They’re not cheerful, they’re just lazy! They like things to be comfortable and relaxed, actually Berliners and Viennese are very similar.”

Now that’s something I couldn’t agree with. In my experience, Berliners have never been such show-offs as the residents of the Austrian capital. Berliners clearly have an inferiority complex and some trouble with self-reflection. For a long time, they didn’t even know what they were supposed to be like until a humorous Berlin mayor enlightened them. They were supposed to be “poor but sexy”. Berliners thought that was okay; they could live with that. It’s good to know what you’re like. In truth, Berliners are as sexy as a sack of potatoes, but it never hurt their self-esteem. In Vienna, on the other hand, every waiter carries himself around with such an air of dignity as if he had been Mozart in a former life or had held a high position at the imperial court. Yet every second one of them has travelled far to be here.

As it turns out, our Viennese friends were newcomers themselves, people who had moved to Vienna from somewhere else a long time ago and had become Viennese. Good thing Vienna is a democratic city. Anyone can become Viennese here if they just sit at the window of a coffeehouse long enough and complain about the Viennese. In the best Viennese tradition, Michael praised our hosts and scorned those uptight Germans. “At least you build the best cars and have the best car magazine in the world,” our friends told us, because praise is considered good etiquette here. By now I’d been in Vienna long enough to wonder if that was meant sincerely or tongue-in-cheek. Was it an honest expression of delight, or that famously ambiguous Viennese humor? Or both at the same time? After a long conversation accompanied by five Melanges, we went out into the fresh air. “Would you look at that!” said Michael. “We didn’t even get a parking ticket.”

Text: Wladimir Kaminer

Photos: Oliver Gast

ramp #64 How About That!

Surprises open our eyes to new things, which now isn’t really a big surprise. The unexpected simply stays in memory longer, sparks curiosity – and prompts action. Essential for adapting to a changing world. The future might just be warming up for progress. It’s meant to move forward effectively. Find out more