Three friends go for a motorcycle ride in Italy. What makes this story interesting is that the friends in question are Harm Lagaaij, Mitja Borkert and Andrea Ferraresi. They are the creative minds behind cars like the new Lamborghini Revuelto and the Temerario, the Porsche Carrera GT and the 993 – and all models of Ducati since 2005.

Mitja Borkert raises an eyebrow, as if he had understood the question but not why we would ask something like that. He thinks about it for a moment, then grins and explains the protocol: “Obviously, you should curtsy, with your nose touching the ground, then count to four, slowly rise, and kiss the signet ring on his right hand. But under no circumstances should you touch the ring!” For clarification: We had asked how we should address Harm Lagaaij, Mitja Borkert’s friend, mentor, former director of Style Porsche and, since 2013, an Officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau, the Dutch equivalent to an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. That honor, awarded by the monarch of the United Kingdom, grants recipients the right to use the title “Sir” before their name and to be addressed as such. But we didn’t know how they do things in the Netherlands. Mitja Borkert had a good laugh with us. Then Harm Lagaaij arrives and solves the mystery of how to address him in the most relaxed manner: “Hi, I’m Harm,” he says, greeting us with his soft Dutch accent. Right off the bat, we’re on a first-name basis. Hey, it’s a biker story.

Harm Lagaaij and Mitja Borkert go way back. Around twenty-five years ago, Lagaaij, then head of design at Style Porsche, discovered a promising young student by the name of Mitja Borkert at Pforzheim University. He brought him to Porsche. Borkert did an internship with Lagaaij, wrote his final thesis paper at Porsche, and was offered a full-time position. His first real salary. “A few weeks later, he showed up riding an MV Agusta F4.” Even today, you can tell just how crazy Lagaaij thought that was. “Sure, it was the most beautiful sports bike at the time,” he recalls, adding, “It was also one of the fastest. I just thought: He won’t survive that.” Lagaaij had seen plenty of young talents before who had spent their first paycheck on a sports car. And more than once, at least the car didn’t survive. With a motorcycle, the odds were even worse. Lagaaij himself had sold his Ducati 916 – which, like the MV Agusta F4, was designed by Massimo Tamburini – just six months after he got it. “On the firm advice of my guardian angel.” But young Borkert had no intention of giving up his Agusta. He rode it for ages. Until he switched to Ducati.

We’re at Mitja Borkert’s home in Modena, where the former MV Agusta rider and current Lamborghini head designer lives. He grins. Andrea Ferraresi laughs when he hears the story. The Ducati head of design is a friend of Borkert’s, and the three men have arranged to meet for a ride. Besides their shared passion for design, they are also united by their love of motorcycling – and Ducati. And that love isn’t any less intense just because it’s raining outside. The date for the outing was set a long time ago. Harm Lagaaij has traveled from near Munich with his Ducati Hypermotard 698 piggybacked on his Porsche Cayenne. “I designed and built the carrier myself. As far as I know, I’ve got the only Cayenne in the world that can carry a motorcycle like that.” Andrea Ferraresi rides a Ducati Diavel. And Mitja Borkert? “The new Ducati Panigale V4.” Borkert looks at Lagaaij: “It’s significantly faster and even more beautiful than the MV from back then.”

The road conditions aren’t good at all. Wet and slippery, a nightmare for motorcyclists. But the machines are manned by experienced riders. Each of them covers thousands of kilometers a year. This is the first time they’ve ridden together, otherwise they tend to ride alone, which is in part because of their job. Lagaaij explains: “When you’re in a group, someone always wants to stop to eat, another one wants something to drink, the third guy has to take a bathroom break. Everyone has different speeds and levels of experience. When I’m by myself, I’m independent.” Mitja Borkert chose the route. From Modena, the three ride up to Madonna di Puianello. Coffee break. Delicate aroma, perfectly tuned espresso machine, high-quality water. In Italy, Borkert has learned the importance of good coffee. Andrea Ferraresi has never known it any other way. The three talk about Mitja Borkert’s youth. He grew up in East Germany, in a town called Herzberg around a hundred kilometers south of Berlin. “I was good at school, but for political reasons the Stasi, or actually my secondary school, wouldn’t let me go to university – unless I joined the army, which was totally out of the question for me. If it hadn’t been for German reunification, I’d probably be a bricklayer today. There was no alternative. For me, the fall of the Wall changed everything. I was able to go to Pforzheim to study Transportation Design and had the opportunity to do what I’d always wanted.” It is a brief, thought-provoking moment. Harm Lagaaij pauses for a minute, then says to us: “Mitja’s talent is one thing. The fact that he stays curious, obviously has a sense of humor and is ambitious, that’s another. But what I haven’t seen often in this form is the energy he displays. I’ve done a lot of projects on the side myself, alongside my very demanding job, and today I wonder where I got the energy for it all. But Mitja is taking that to a whole new level.”

Borkert has to leave us for a moment to go to the Lamborghini headquarters. “An important appointment, there was no other way.” We are left alone with Harm Lagaaij and Andrea Ferraresi for an hour or two. The topic: Ducati. What else? “I’m an engineer by training,” says Ferraresi. He came to design through Walter de Silva. The Italian car designer mentored him and convinced him to develop the new design line for Ducati. Lagaaij likes it. He’s convinced that Ducati has built the best and most beautiful motorcycles in recent years. That’s why he switched to Ducati. “Letting an engineer develop the design, a person who can mediate between the technical and the design side of things because he understands both, has worked really well for Ducati for quite a while. They’ve created an amazing situation for themselves. And it’ll be very exciting to see where they go from here.” Ferraresi nods. “We want to continue to differentiate ourselves through innovation and excellence in design and technology,” he says, “We are seeing an increased presence of Chinese brands on the market, similar to the situation in the seventies with the Japanese. And the competition is using some pretty aggressive pricing models.” Then he explains the Panigale V4’s new eCBS braking system to Harm Lagaaij. It allows riders to brake much later than usual when leaning. When the brakes are released, they release only the front wheel while providing a brief burst of braking power at the rear. This causes the bike to turn more sharply inwards. MotoGP professionals do the same thing intuitively with their foot. Now this has been translated into digital technology for the entire braking system. Harm Lagaaij listens attentively. He has one question: “Does Mitja know about this?” Ferraresi laughs. “What was your first Ducati?” he wants to know. “A 1982 900 SS Bevel Drive.” Ferraresi nods. Lagaaij continues: “A typical example of a Ducati where the engine is the best part. But the frame doesn’t match the engine.” “Absolutely right,” Ferraresi agrees. Lagaaij goes on to explain a brief but intense affair with a 916 when Ferraresi interjects: “Our entire design strategy is based on two motorcycles: the Monster and the 916. We take our lead from both of these models.”

Meanwhile, it has stopped raining. The streets dry quickly in Emilia Romagna. Mitja Borkert sends a message:

“Going to be a while longer. But we can meet at the track in Modena later. See you there. Best, Mitja.”

Lagaaij reaches for his helmet. “I think we should go. We don’t want Mitja to get there before us.” We arrive at the track about ten minutes before Borkert. “Not that it matters,” says Lagaaij, “but it’s okay to include that in your article.” Then things get loud. A guy from Lamborghini starts up a Revuelto, while a brand-new Temerario is waiting in the pit lane. In both cases, Mitja Borkert is the lead designer in charge. While the twelve-cylinder engine roars to life, Ferraresi and Lagaaij examine the Temerario. Ferraresi points to the rear, in particular to the exposed rear wheels. “That was inspired by sports bikes.” Borkert has already incorporated this into the design language of some of the last Huracán derivatives. The Lamborghini designer finally shows up, still holding his helmet. “Lamborghini is design and performance,” he explains. “That’s the story we’re telling. It’s compelling and credible. Incorporating derivatives from sports motorcycles was logical for me from the outset.” The other way around – and here all three agree – is much more difficult. “You can’t compare motorcycle and automobile design, even if it’s a sports car,” says Lagaaij, who still works as a consultant in the automobile industry today. A conversation ensues in which you can feel the passion for design. Lagaaij stresses that today, with the increased value placed on design, significantly higher design budgets and much better technological possibilities, it is all the more important to adhere to proper design processes in order to develop truly attractive production vehicles. Then Borkert says, “Hey, we can hit the track!” The rest of the time is spent not so much talking as riding – until the sun goes down

Around twenty-five years ago, Harm Lagaaij, then head of design at Style Porsche, discovered a promising young student by the name of Mitja Borkert.

“Our entire design strategy is based on two motorcycles: the Monster and the 916. We take our lead from both of these models.” (Andrea Ferraresi)

Andrea Ferraresi was born on July 14, 1968, in Mirandola in the Province of Modena and studied aerodynamics and aeronautical engineering. Since joining Ducati in 2000, all of the brand’s superbikes have been developed with his input as project manager. Ferraresi was appointed director of Ducati Centro Stile in 2005. Since then, all Ducati models – the 1098, the Hypermotard, the Monster, the Streetfighter, the Multistrada, the Diavel, the XDiavel, the 1199 Panigale and the Panigale V4 – bear his signature. He is also responsible for the brand’s corporate and product strategy and for the brand identity at all points of contact between Ducati and its customers, from dealers to apparel to licensed products.

Harm Lagaaij was born on December 28, 1946, in The Hague. After completing his training at IVA (Institute for Automobiles) in Driebergen, he started working at Dutch company Olyslager in 1968 before moving to Porsche as a designer in 1971. He then held leading design positions at Ford and BMW Technik, overseeing the development of the Ford Escort, the Ford Sierra and the BMW Z1, among others. Lagaaij returned to Porsche in 1989. As the director of Style Porsche, he played a key role in shaping Porsche’s future with the design of the 993, 996 and 997 models of the 911 series as well as the Boxster, Cayenne and Carrera GT. In 2013 Lagaaij was made an Officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau, a civil and military Dutch order of chivalry. He has been a design consultant for the automotive industry since 2021.

Mitja Borkert was born in Herzberg in Brandenburg on March 17, 1974, and studied transportation design at Pforzheim University. He began his career at Porsche, where he served as Head of Advanced Design and as Head of Exteriors. His work there included the Cayenne, the 987 Boxster FL, the Macan, the Mission E, the Panamera Sport Turismo Concept, the 917 Concept, the 904 Living Legend and the 911 Safari. Since April 2016, Borkert has been Head of Design at Lamborghini, where he created the Terzo Millennio electric concept, the Sián and the Sián Roadster (the first hybrid production vehicles from Lamborghini), the track-only Essenza SCV12, the Lambo V12 Vision Gran Turismo (for the video game Gran Turismo), the Huracán STO and the Huracán EVO+. His latest models are the Revuelto and the Temerario.

“Lamborghini is design and performance. Incorporating derivatives from sports motorcycles was logical for me from the outset.” (Mitja Borkert)

“If it hadn’t been for German reunification, I’d probably be a bricklayer in East Germany today. There was no alternative. (Mitja Borkert)

Text: Matthias Mederer

Photos: Oliver Gast

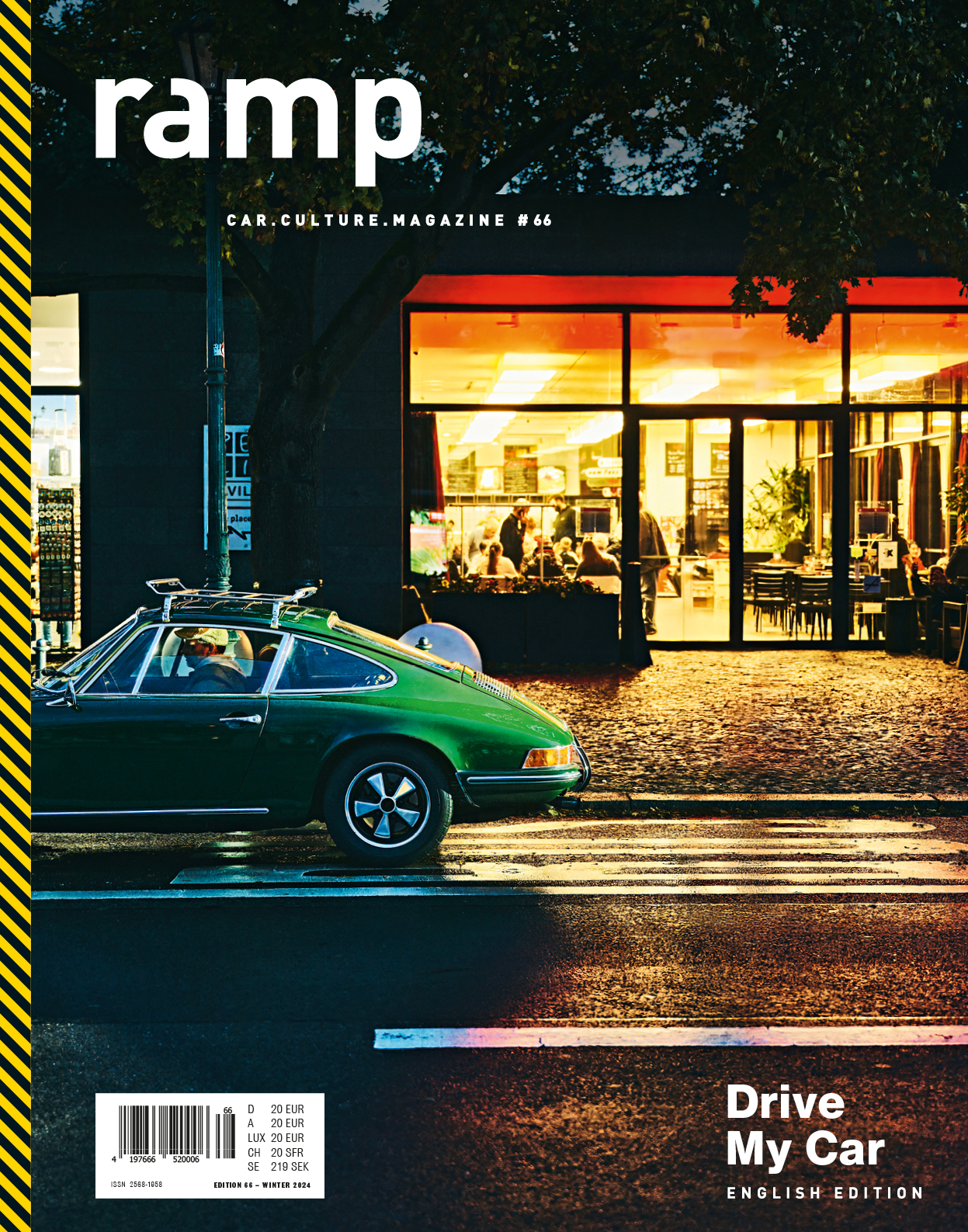

ramp #66: Drive My Car

A three-hour Japanese drama where nothing much appears to happen other than endless car rides and which is somehow about the multilingual production of a stage play may not immediately seem like something that could arouse your curiosity. Though it should. For us, these 179 minutes served as inspiration for the title to our latest issue of ramp. Find out more