From a young boy watching racing in his native Ulster to competing, and winning, in both trials and road racing, legendary motorcycle rider Sammy Miller MBE has dedicated his life to motorcycle racing. Now in his late eighties, his passion is still as strong as it ever was, and most days he can be found restoring yet another bike for the Sammy Miller Motorcycle Museum in the New Forest, England. Our partner MOTUL gave Sammy a call to find out more about his life on two wheels.

Sammy, you’ve had an incredible motorcycle career. You’ve been a trials rider, and a road racer, which is unusual. How difficult was it to compete at a high level in such different motorsports?

Well, in those days, there were two seasons: trials in the winter and road racing in the summer. And both helped each other along because it was all about riding abilities, throttle control, dedication and concentration. Quite a few riders actually had a go at trial riding but were never any good. Luckily, I excelled at both. I think it’s more skillful to do trials riding than road racing. But road racing is a lot more exciting, a lot more dangerous. Both require absolute dedication, concentration and throttle control.

Why do you think riders nowadays specialise in one area unlike when you raced?

Each sector of the sport is so specialised that you couldn’t even fit in riding another branch because they’re testing all winter. They’re riding all the time and preparing. In my days, the road racing finished in September and that was it until May. Now it goes on all year all over the world and there are test days all over the place. But again, when I was winning and racing, it was like me and maybe one mechanic. And now you get Lewis Hamilton with 1200 people looking after him.

Was racing more exciting in your days?

It was much more exciting and much more dangerous. That’s one of the reasons why I went from road racing to trials, because I thought it’d be a better idea to be an old successful trials rider than a dead road racer. We were losing a friend every week.

Thankfully, it’s improved a bit since then.

It’s improved immensely. The circuits are much safer. The North West 200 is a lot safer. The safety has helped the job along immensely.

You’ve obviously got a really deep passion for motorbikes. Where does that come from?

Well, if you come from Northern Ireland, it’s born and bred into you. I remember when we were kids at Templepatrick, seeing the guys testing bikes up and down the Antrim Mile. We have so many great races like the Ulster GP and the North West 200. It was the ultimate. I started getting a passion for it at about 10 years old, and here I am, still playing with motorbikes.

At what point then did you decide to create a museum?

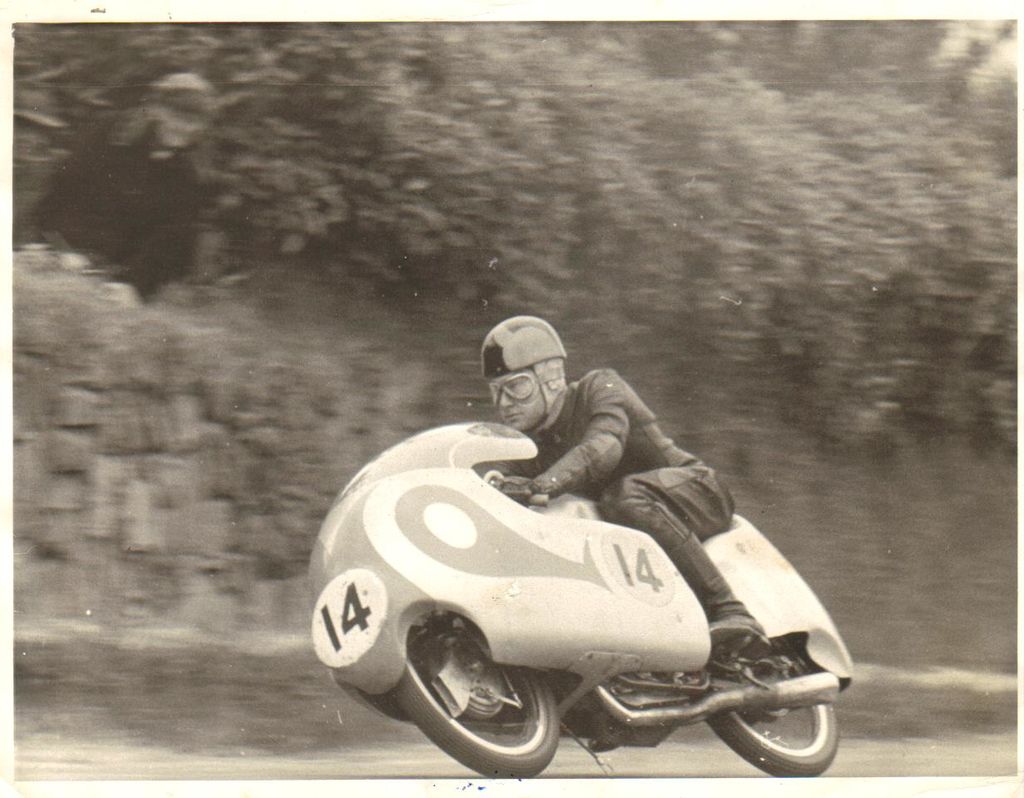

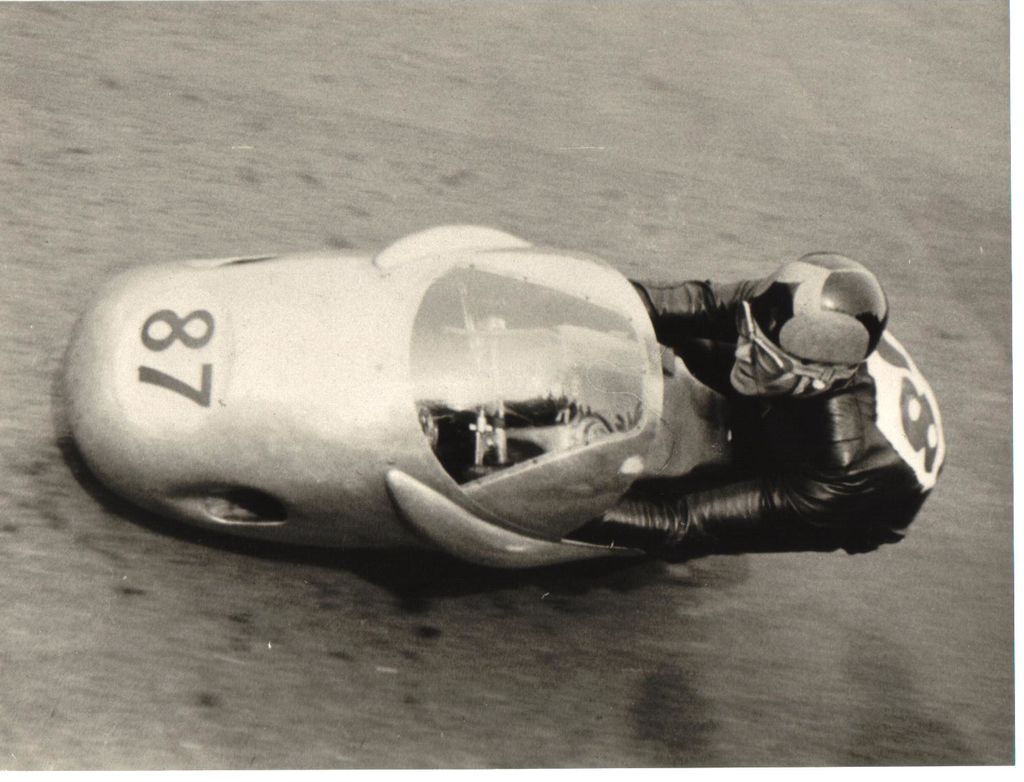

After retiring from international events, in about 1970, all of a sudden, I got the idea that it’d be nice to have some of my old racing bikes. The North West 200 NSU, the bike I won the Cookstown on, the Norton I won the Munster on, and so on. So I started collecting all my old racing and trials bikes. The double garage at home wasn’t big enough. I extended that, and that wasn’t big enough. And then we had a business in New Milton, and there was a big barn at the back of the premises. We converted that into the first museum. And then that wasn’t big enough. So, 25 years ago, we bought this complex, where we are now at Bashley Manor. And it’s just a passion that got out of control.

How does it make you feel, seeing how it has grown?

It’s absolutely wonderful. It’s been a passion to gather up all those phenomenal racing bikes from around the world. We want to preserve the heritage of motorcycling. We have bikes from over 100 years old at the museum, right up to relatively modern stuff and all the classic racers. Probably the best is that V4 supercharged liquid-cooled AJS that Walter Rusk set the first 100-mile-an-hour lap in the 1939 Ulster Grand Prix. And that was some achievement. To have that bike, the first bike to win a world championship, the AJS Porcupine. I work in the restoration department and to restore an old wreck of a bike that hasn’t run for 80 years, rebuild it and take it out into the courtyard and fire it up and have a ride on it, well there’s nothing that beats that for me.

Your museum has been regarded as, possibly, the world’s best collection of motorcycles. And you’ve got 400 bikes. Where do the bikes come from? Are they loans from collectors or do you own them?

We’re up to nearly 500 bikes. A few bikes are on loan, but we’ve got a museum trust, and there are some trustees that sponsor us. This means we’ve got some finance to purchase these bikes.

You also spend a lot of time in the workshop. Is that the most satisfying part for you?

Only six days a week [laughs]. I’m down to six days now from seven. It’s very satisfying. The world is full of great thinkers, but very few doers.

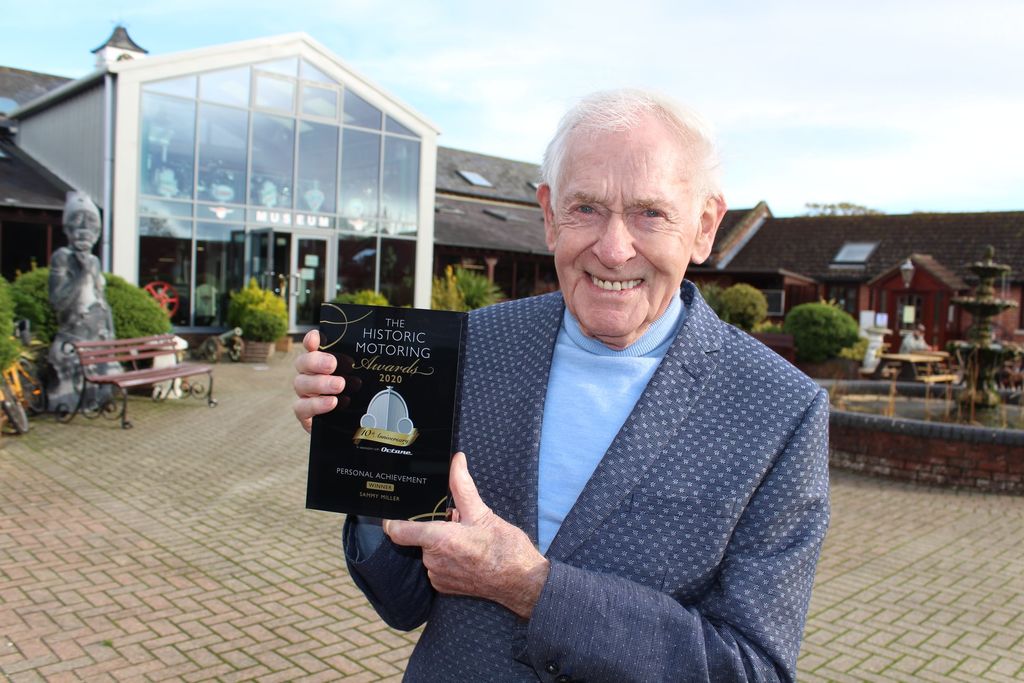

You’ve been very well recognized for your work. How does that make you feel?

It’s an achievement, but you never want to keep looking back. You want to keep looking forward. But it’s nice to be acknowledged for preserving the British heritage of motorcycling.

Report by motul.com