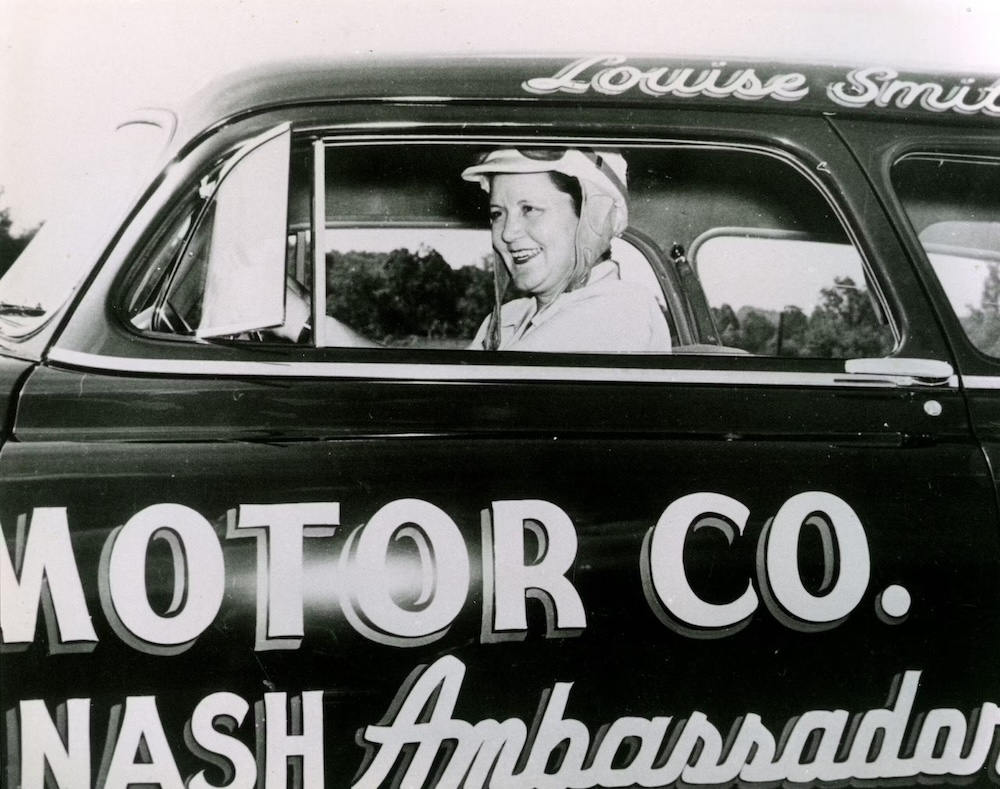

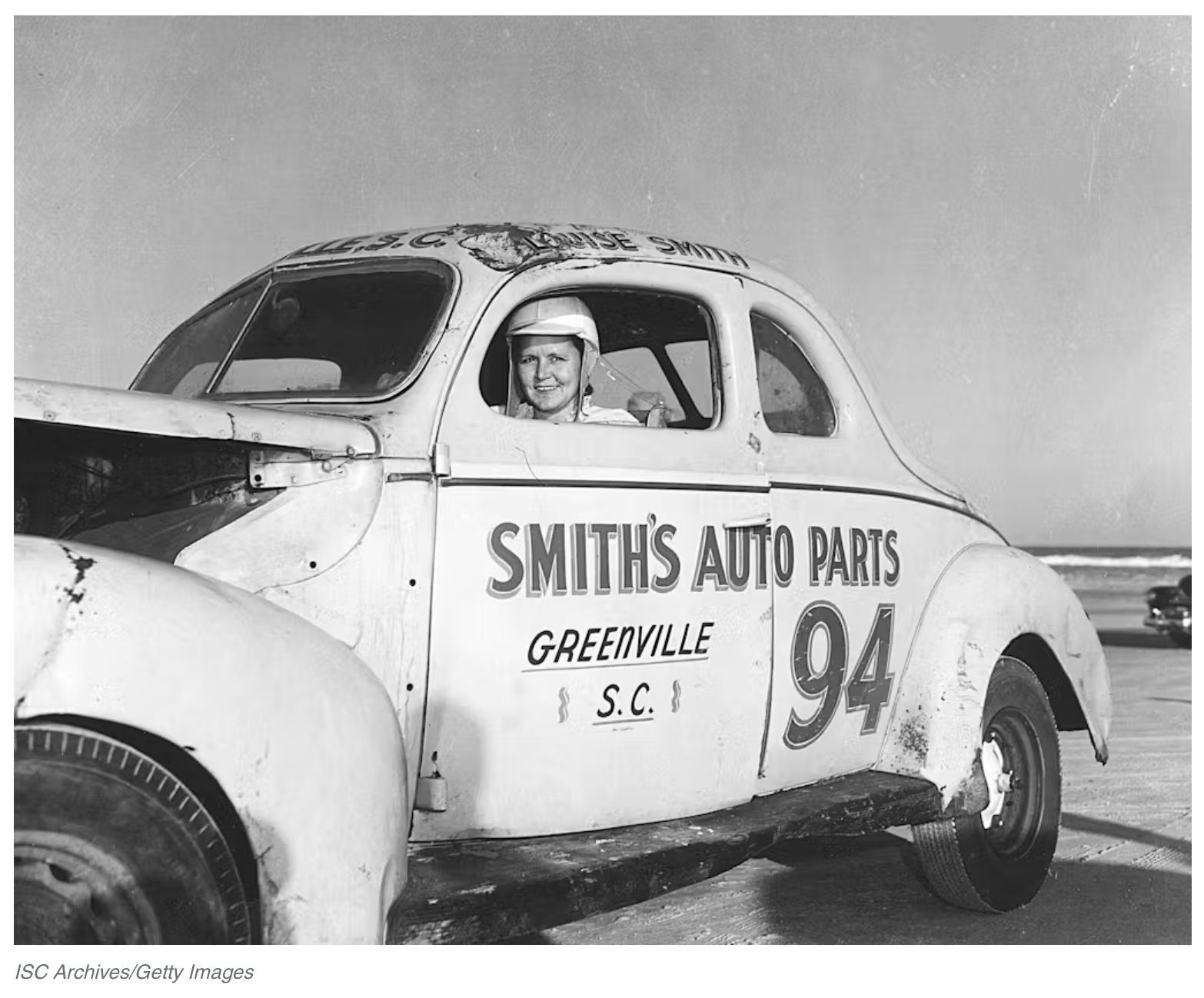

In 1999 an 83-year-old from Greenville, South Carolina became the first woman to be inducted into the International Motor Sports Hall of Fame, located in Talladega, Alabama. Her name was Louise Smith, and it was her hard and fast driving in the early days of NASCAR that the Hall finally recognized, decades after she retired from racing.

Back in 1946, post-war America was full of entrepreneurs. Race promoter Bill France was one of them, hoping to make a fortune with his Shine Car race series. But the crowds were typically small, and France needed to boost the takings at the Greenville-Pickens track in South Carolina. He had heard about a local female driver, and the extra publicity of having a woman on the track would be just the ticket.

“Everyone around here knew about me,” Smith recalled when I interviewed her just six years before she passed away at the age of 89.

“We all had souped-up cars and I’d outrun every lawman in South Carolina. I’d never even seen a race before, but I was a crazy driver and they wanted some woman to draw the crowds,” she said.

Like many that were to come, Louise’s first race was full of drama. “They didn’t even let me drive the car before the race, so I had no practice. All they told me was that if I saw a red flag to stop. When the race was over, I was third. I saw all the cars come in, but I didn’t see a red flag, so I kept going. Nobody said nothin’ to me about no checkered flag. Eventually they figured it out and showed me a red flag.”

It was the start of a decade of racing in which Louise would notch 38 victories. “I did so well that Bill called me a few days later and asked me to go to New Jersey. I started traveling all over—New York, Canada, and all over the South,” she added.

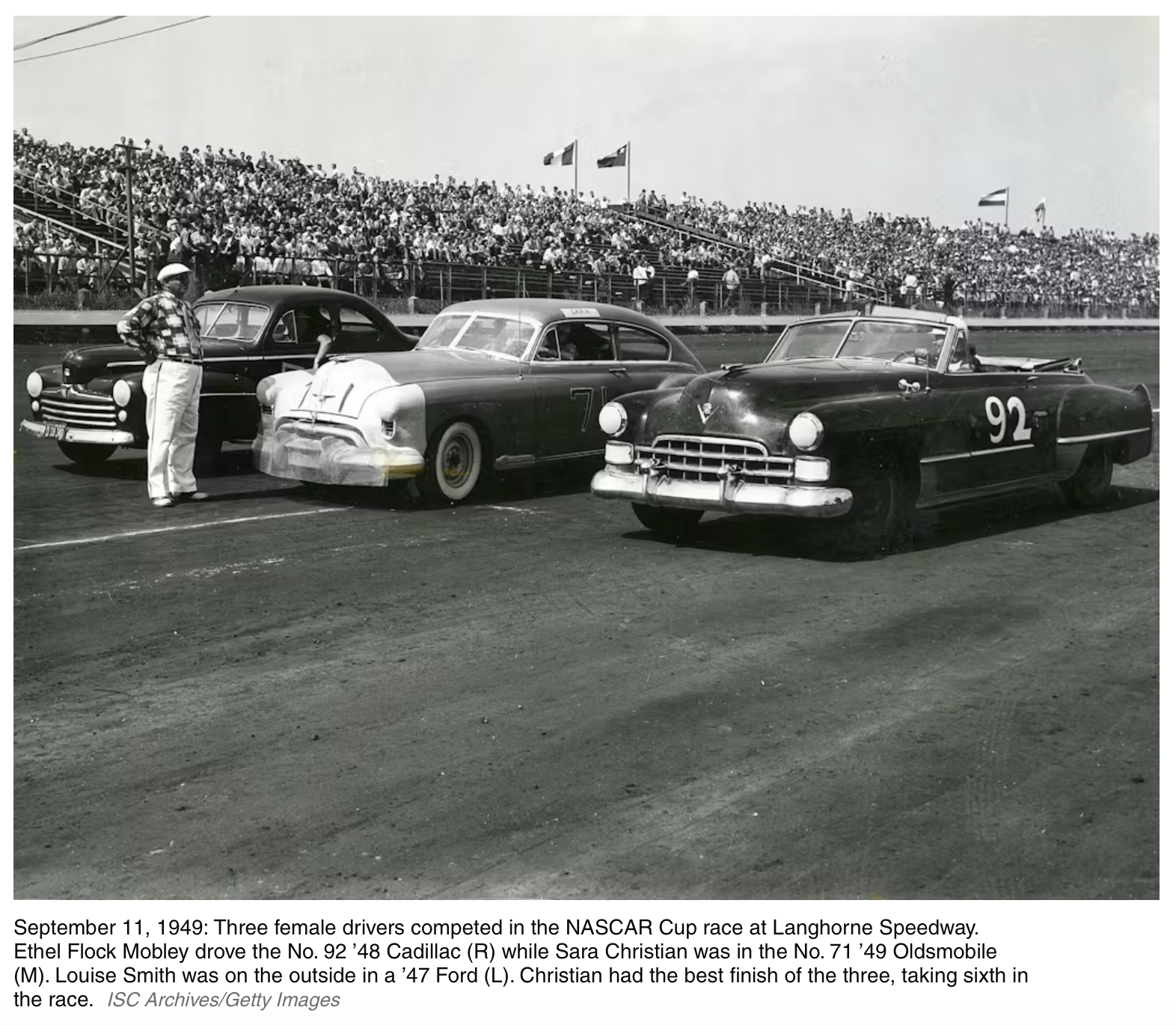

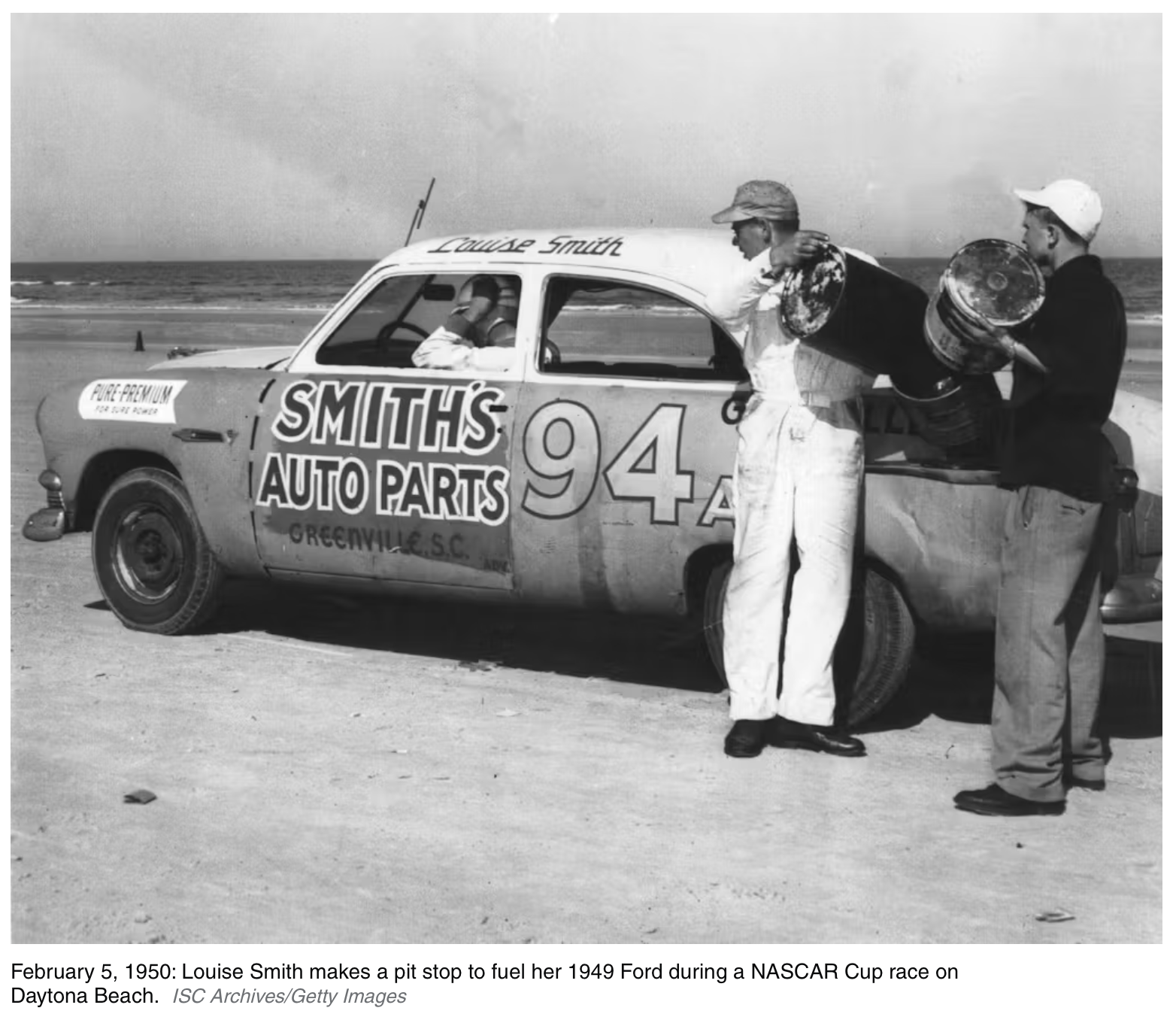

The Shine Car series toured North America and its following increased. On December 14, 1947, Bill France officially organized the first meeting of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing at Daytona Beach, Florida. Racing was timed between the tides to make for the longest possible course and the cars, as the name suggests, were stock—no roll cages, no safety equipment, just as they left the factory.

Getting hold of a new car immediately after the war was difficult, but with Louise’s husband Noah in the auto business, he was able to pull in a few favors and find her a new Ford in 1947. He had no idea what was to become of it.

“My husband had just got out of the service, and he didn’t know nothin’ about me racing,” she remembered. “He got me a ’47 Ford Coupe and I said that I wanted to go to Daytona on vacation. A friend of mine got me a souped-up motor which we put in the back of the car for when we got there. I drew number 13, and I tried everything to trade it off, I even tried to pay someone to take it. At Daytona you couldn’t see anything because of the sand. The five cars ahead of me piled up and I hit them, I went up in the air and rolled over and over. Some policemen put the car back on its wheels and bashed the roof out and I carried on and finished 13th.

“I left the car in Augusta to have it fixed and I caught the bus home. When I walked into my husband’s office the first thing he said was: ‘Where’s the car?’ And I said that he’d bought a lemon that had broken down and I’d had to leave it in Augusta. Then he went behind the counter and pulled out a newspaper and in big letters it said, ‘Louise Smith wrecks in Daytona.’ I just turned around and left. I didn’t know if he was going to shoot me or what.”

But Noah didn’t produce a gun. Instead, he put his mechanics at her disposal and provided cars from his junkyard that could be turned into racers. He didn’t exactly relish the prospect of his wife racing, but he knew she was far too strong-willed for him to stop her.

“He only watched me race once,” Smith told me. “My car skidded, went up on two wheels, and apparently he nearly swallowed his cigar. He never went to another race, but he had his boys look after the cars for me.”

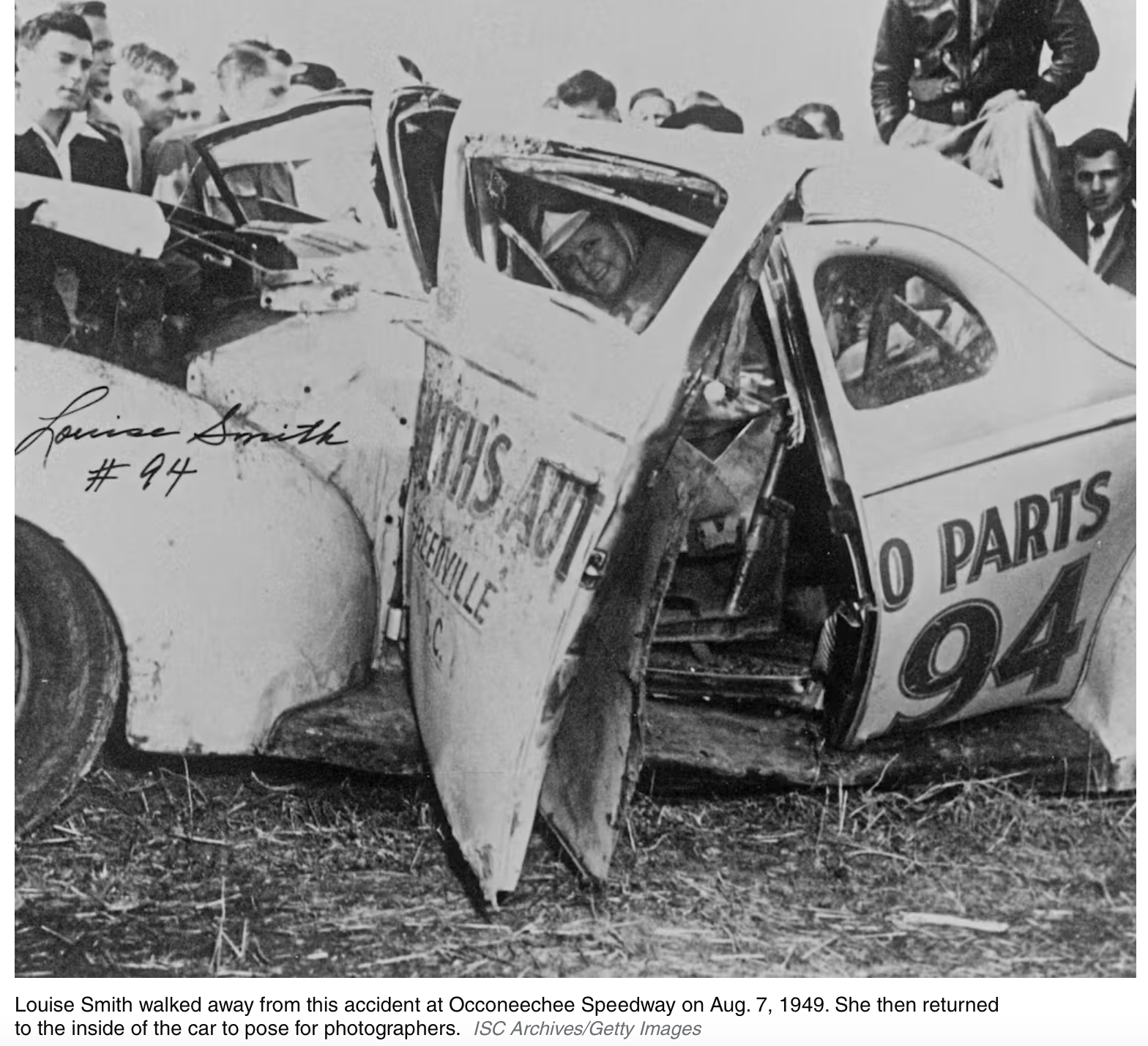

The crash at Daytona was one of many. Indeed, Louise was almost more famous for her wrecks than her race wins.

“At Mobile this guy didn’t want to drive with me at all,” she recalled. “He was the only one who objected, and the promoters sided with me. Before the race he sidled up to me and said he was going to put me in the lake. So, I decided I’d put him in the lake. My mind was working on that all race, but when I hit him, I spun twice and ended up in the water. I had to sit on the trunk and wait for the race to finish.”

Was she deterred? Not a bit. In practice one time Louise wrecked her race car, but rather than sit out the event, she just drove her tow car instead. When it came to racing, nothing would get in her way.

“In my worst wreck at Hillsborough [North Carolina] it took them 36 minutes to get me out of the car with an acetylene torch. I had 48 stitches and four pins in my leg after that. There was no safety equipment in those days. You used to get hot oil coming inside the car and burning your legs. You knew they were burning but you kept going anyway. And because gas was so scarce, we ran the cars on ether and alcohol so they’d either blow you up or put you to sleep.”

Alcohol wasn’t just used to fuel the cars; it funded many a competitor as well. Although Prohibition had officially ended in many states, in the post-war austerity era, alcohol, when you could get it, was expensive and the moonshiners did a roaring trade. The new touring race series was the perfect way to transport the contraband booze. The drivers were desperate for money to keep racing, and their cars were fast enough to outrun the authorities.

“Back then they had to bootleg to get from one race to another. At one race in Tennessee, a very famous driver who I’ll not name was loaded with liquor which he had to deliver. He won the race and then went out the back stretch and didn’t come back for his money as he had to deliver the liquor. His pit crew had to say he’d gone to the restroom.

“All my friends ran bootleg as nobody had any money,” said Smith. “If you won a race, you were lucky to get $100. I raced all over the country and the most I ever got was $700 at Buffalo. Sometimes it seemed like the more you drove the less money you had.”

And if actually winning the money was tough, holding on to it was often even tougher.

“We had to fight for the prize money. Unless you were way out in front, they had no way of telling who had won as we didn’t have any accurate timing equipment. Buck Baker won a race in Greenwood, and as soon as the race was over people started running up to him and punching him. I wasn’t driving that night, and I came down from the grandstand and went out there and started helping him with a tire iron.”

After one race a ruckus erupted between several drivers in a restaurant. Louise escaped arrest only because she happened to be in the ladies’ room at the time. To raise bail for her friends she pawned her diamond ring.

“Of course there’s still fights today, but now they get fines. They couldn’t fine us as we didn’t have no money.”

Sitting in her parlor surrounded by polished silverware and lacy doilies adorning every flat surface, it was hard to imagine this Southern belle was ever in a brawl.

“They used to say ‘Watch out for Louise, she might shoot you!’” she chuckled.

It’s good that Louise was never shy of a fight as getting into the Hall of Fame was a battle in itself. She was nominated and turned down three times before finally being accepted.

“It was really tough to get in,” she told me. “I said to them if you’re ever going to put me in, do it before I die. It ain’t no good to me after that.”

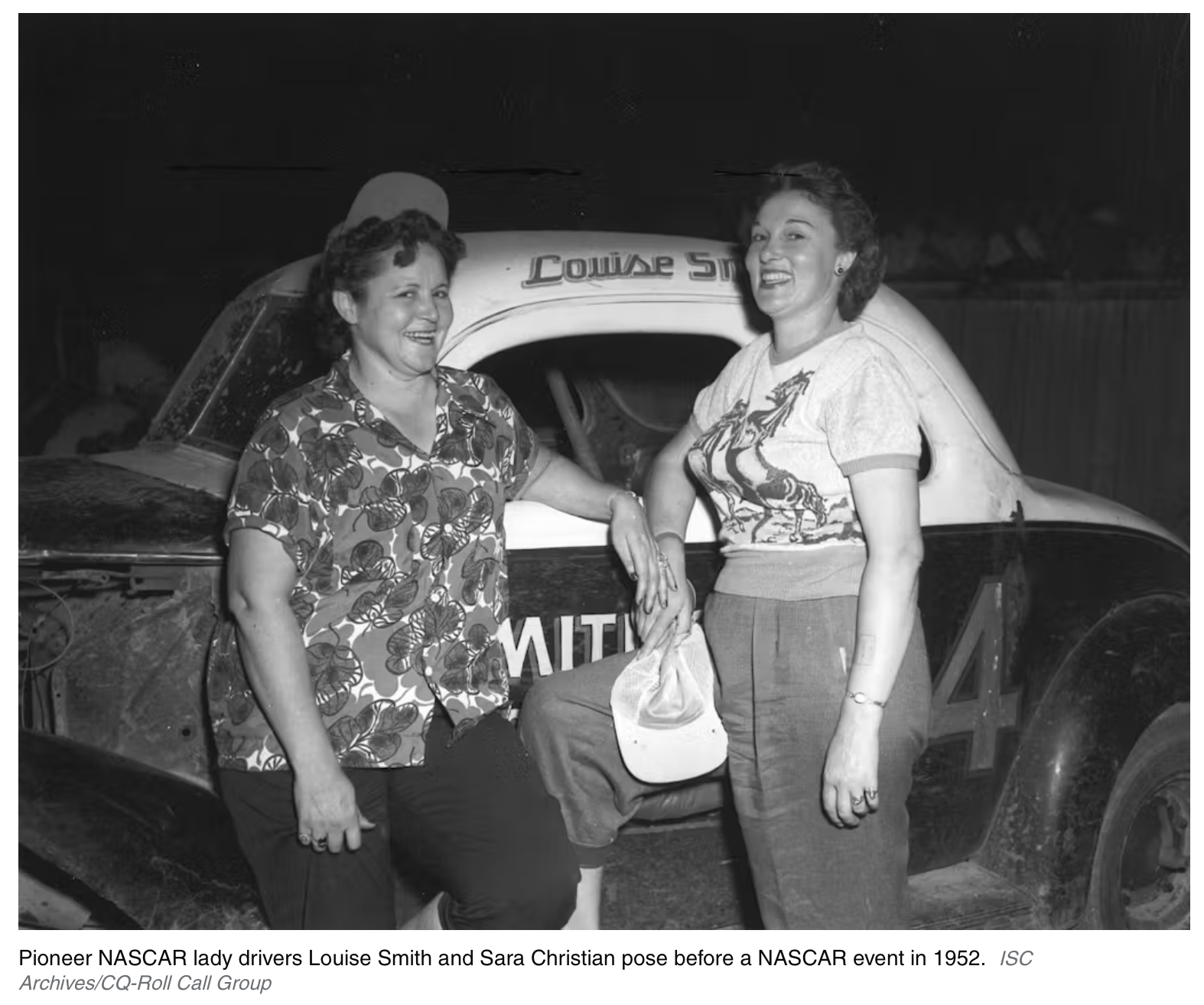

In the male-dominated world of motorsports, Louise was the first lady acknowledged at this level for her contribution, paving the way for drag racer Shirley Muldowney to be inducted in 2004 and NASCAR and IndyCar racer Janet Guthrie in 2006.

“The other drivers didn’t like me when I raced because I was a woman, and they liked me even less when I beat them,” said Smith.

“But I won a lot, crashed a lot and broke just about every bone in my body. I gave it everything I had, and I honestly think I made a big enough impact to get in the Hall.”

Finally accepted, Louise was still defiant. “They gave me a ring to commemorate it, but it’s a man’s ring,” she complained.

Report by Nik Berg for hagerty.com