The whirring noise penetrates the cramped cabin bright and loud. The speedometer shows just 3500 rpm, but it sounds more like 9000. The engine gets louder with every additional revolution, more reminiscent of a jet than a classic car. Unusual, but then the entire car is—a 1970 Mercedes-Benz C 111 with a Wankel rotary engine. No Mercedes from the era is more spectacular than this.

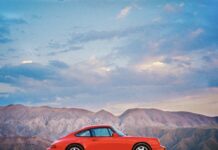

Just 55 years ago, the look alone was a statement: Ultra-flat and painted bright orange, the Bruno Sacco–designed C111 was intended to herald the future and initiate technological advances. At first glance, the then-new aerodynamic solutions, the folding headlights, the flat hood, and the nostrils are striking. Mercedes also experimented with gullwing doors and a body made of fiber-reinforced plastic (FRP), which was bolted to the sheet steel frame. The two-seater’s height is a low 3 feet 7 inches, the entire body measuring just under 14 and a half feet.

In 1969, the rear of the first C111 featured a small sensation: a three-rotor Wankel engine with direct injection and 280 hp. A year later, in the C111 II, this car, Mercedes engineers fitted a larger, more powerful unit with four rotors. Even today, the engine is a marvel.

A few months ago, Mercedes-Benz found a suitable engine, got it running again, transplanted it into a C111 II that had been sitting for 18 years in the company’s Stuttgart museum, and brought the prototype to Monterey Car Week. At Salinas Airport, outside of Monterey, the taxiways were clear and the C111 was ready to be driven.

This test car, with internal number 33, is the third vehicle of the second series, built around August 1970 and painted in the not-so-subtle orange metallic color “Weißherbst,” which translates to “White Autumn.”

The gullwing doors open high to reveal a cramped interior, and you step into the time machine over the wide side sills, which requires a little contortion. Once inside, you and your co-pilot lie down more than you sit, and you slither a four-point harness over your shoulders and hips to keep you snug.

Although it is only a prototype, the Benz doesn’t look or feel like one. The seats are leather with fabric inserts in a wonderful Pepita pattern. There is air conditioning, and developers even gave period test drivers a radio, which is strange, because the best sound comes from the engine.

Once the doors are closed, from the driver’s seat you can casually rest your left arm on the wide sill. It is safer, however, to keep both hands on the steering wheel. Engage first gear at the bottom left, release the hard clutch—the pick-up point is a bit tough to discern—and listen to the Wankel howl as you accelerate. It is quick to 2000, 3000, 4000 rpm. At 4600 rpm, the engine is already producing 250 hp, and by 7000, output is 350 hp. The mechanic in the passenger seat grips his seat nervously and politely asks me not to overdo it. “We’ve just overhauled the engine and there are simply no spare parts,” he says.

Yes, some healthy respect for the age of the car is in order, so I shift through subsequent gears in the four-speed gearbox at 4500 rpm before braking at the end of the taxiway to turn 180 degrees. A quick downshift and flooring of the accelerator, and there’s plenty of power to exit the bend. Despite its age, the Benz turns accurately, the 215/70R15 Michelins start to whine slightly, the rear end bounces gently, and then the fun starts all over again: Accelerate, listen to that turbine-like sound, shift, and become intoxicated by the speed, all without engine vibrations. Again and again and again.

Mercedes built four iterations of the C111 between 1969 and 1978—17 cars in all. The first two versions were Wankel-powered. The C111 III was powered by a three-liter five-cylinder diesel. The final iteration ran the 3.5-liter V-8 that powered the 300 SEL 3.5 and 280 SE 3.5, though for a later record run, this was replaced with a twin-turbocharged 4.5-liter V-8. The advantages of the smooth-running, nearly vibration-free rotary become increasingly clear with every shift. Where a V-8 would rumble and a diesel would rattle, the Wankel just hums along. All while offering breathtaking driving performance in a design that still looks futuristic. What must it have looked like 55 years ago?

Mercedes first presented the C111 I in September 1969 at the Frankfurt Motor Show, then brought it to America in February 1970 for the Chicago Auto Show. Fans of the brand went crazy, hoping for a successor to the legendary W198 300SL Gullwing. It has been reported that customers sent blank checks to the company headquarters in order to get their hands on a car. But the one-off was only built to test new technologies. Mercedes went public with the revised Type II body in March 1970, which went on display that month at the Geneva Motor Show. A four-rotor Wankel engine (M950) with a chamber volume of 600 cc was now at work in the rear. With a low compression ratio of 9:1 and mechanical direct fuel injection, the engine produced 319 lb-ft of torque and 350 hp at 7000 rpm. This enabled the aerodynamic coupe to sprint to 62 mph in 4.8 seconds and reach speeds of up to 180 mph—both stellar figures for 1970.

Felix Wankel’s concept of a rotary engine dates back to the 1920s, but it wasn’t until 1954 that he fully developed one at German carmaker NSU. In contrast to a reciprocating-piston engine, the Wankel had no oscillating masses and no free inertia forces, its triangular-shaped “piston” instead rotating eccentrically in an oval chamber. By the early ’60s, several manufacturers, including Mazda, General Motors, Citroën, and Mercedes-Benz, began experimenting with the technology. In 1963, NSU put the engine into production in its Wankel Spider and again in 1967 in the Ro 80, the same year Mazda debuted the rotary-powered Cosmo. The engine’s mainstream breakthrough would arrive in 1979 with the RX-7 sports car.

Back in Stuttgart, Mercedes engineers had been thinking about a technology for a small, lightweight sports car below the SL Pagoda (W113) since 1963. With the testbed C111 II, the engine was to be developed to series maturity.

In 1973, however, the first oil crisis hit and nobody wanted anything more to do with sports cars, let alone a Wankel engine. The rotary was far too thirsty, requiring up to 50 percent more fuel than a comparable V-8. And despite their small size, they also relied on a great deal of lubrication, which was a problem because the chambers didn’t exactly seal properly. The Wankel would therefore not pass new emissions regulations, especially not in particularly strict California.

Mercedes finally shelved its Wankel aspirations in 1976, but not the C111. Instead, the carmaker broke new ground with the diesel-powered variant, which was aimed more in the direction of endurance and low consumption. The diesel C111 III established a number of records over the next few years, as did the C111 IV with its 493-hp twin-turbo V-8 petrol engine, which in 1979 set a world circuit record of 251 mph on the high-speed track in Nardo, Italy. Of the 17 prototypes built, two were pure show cars and four were scrapped; the 13 remaining examples belong to the Mercedes-Benz Museum.

Mercedes could have shaken up the sports car world with a production version of the C111, but the Swabians decided otherwise. The car was so far ahead of its time that it still looks relevant today. And yet it was never intended to be more than an experimental car, a visionary model that looked ahead and pushed the boundaries. And which hums so wonderfully, bright and loud, to this day.

Report by Fabian Hoberg for hagerty.com