An Honest Day’s Work. Driving in its purest form: clutch and gearshift, no power steering or electronic driver-assistance systems. Yes, such a beast still exists. It’s the De Tomaso Pantera.

Sunday, June 21, 1970. The Formula One Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort: It’s sunny and warm, with a light breeze blowing in from the sea over the dunes. On lap twenty-three, Jochen Rindt (Lotus) is in the lead, shooting through the ultra-fast daredevil-worthy Tunnel Oost. Behind him in seventh place is his close friend Piers Courage, an Englishman, an Eton graduate and one of the last gentleman drivers. His car spins out of control, crashing through a safety fence and slamming into an embankment. The impact is so violent that his helmet is torn off his head. Courage is probably dead by now. The car careens backward, rolling over several times before it bursts into flames. The grass and a few trees at the side of the track are also scorched. An inferno of a blaze. But the race goes on. One death is no reason to stop the race. Rindt wins and stands on the podium with a petrified look on his face. Eleven weeks later – at Monza – he too will be dead.

Courage died in a De Tomaso. The cause of the accident was probably a broken suspension

Things couldn’t have been worse, one thought, for the lanky Argentine of Italian descent, who always wore only suits of the finest cloth and the widest ties and softest kerchiefs in the whole Emilia-Romagna region and, with his dark hair and high forehead, reminded you of the existentialists from the Parisian circle around Jean-Paul Sartre (he was also constantly seen with a cigarette in his hand): Alejandro de Tomaso, forty-two years old, ex-racing driver (a couple of class victories in endurance races, two F1 starts in the 1950s), ex-team head of the now long-defunct Scuderia De Tomaso. In the early 1960s, the Modena-based racing team put the worst fiascoes of the F1 1.5-liter era on the starting grid. They used mainly weak, mass-produced Alfa Romeo engines (Giulietta series) and tuned them until the connecting rods bent and all the magic went up in smoke in a huge bang. For those not so particularly interested in the engineering: The F1 De Tomaso was a steroid-fueled soapbox racer that was unscrupulously sent up to the big leagues where it could only die a cruel death. The De Tomaso was also outfitted with OSCA engines (from the Maserati brothers), but people always thought it was “Oscar” and tended to associate it with Oskar Matzerath, a character with a piercing shriek from Günter Grass’s novel The Tin Drum.

Alejandro was forced to admit that in Formula One he had bitten off more than he could chew. Malicious tongues whispered that the son of a politician and cattle farmer from Buenos Aires would have been better off staying on the other side of the Atlantic tending his cows. After all, he obviously knew as much about car racing as a dairymaid knows about deep-sea diving. But Alejandro switched gears and began producing sports cars for the road. That was a damn good idea, because he gave the world the De Tomaso Pantera. He dipped his toe back in the F1 scene in 1970 to better market this mid-engine two-seater with a self-supporting sheet steel body. Teaming up with constructor Gian Paolo Dallara and the Frank Williams Racing Cars team, he created the De Tomaso 505, the one in which Piers Courage raced to his death in the fifth race of the season. Finally, Alejandro de Tomaso had had enough of F1.

In the beginning was the Vallelunga. The first road sports car from De Tomaso Automobili in 1963, named after the racetrack near Rome, had – as the first Italian sports car ever – a central tubular frame and a mid-engine (in-line four-cylinder cribbed from the Ford Cortina). The car was so flat and light that two lumberjacks could carry it. There was enough room inside for one and a half pygmies, but they couldn’t have too much meat on their bones. The Vallelunga was followed three years later by the Mangusta, which is the Italian word for mongoose, a small and extremely fast predator that can kill a cobra. It’s not hard to guess that the Mangusta was meant to be a match for Carroll Shelby’s (smaller) AC Cobra. Its snout jutted downward, giving it a tremendously diabolical look. And it had gullwing doors in the back, so when you flipped them up, it was like the overeager Ford V8 was jumping at your throat (Señor de Tomaso always had a special fondness for full-on Yankee engines, only he wasn’t allowed to put them in his F1 cars). Neither model was a great success, however, with fewer than five hundred units leaving the factory. This was due in no small part to limited production and distribution capacities.

In 1969 things changed dramatically. De Tomaso struck a major deal with Ford. The Americans were keen on the Mangusta’s successor, the Pantera, with its 351 Cleveland Ford 5.7-liter V8 lifted directly from the world of motorsport. It offered a roomier interior than the Mangusta, had a bigger trunk (or two: back and front!) as well as air conditioning and power windows even back then, with the prospect of a few buyers on the West Coast and in the Sunshine State. Yes, the Pantera was more “workaday” than the Mangusta, if you can even use that word when describing a thoroughbred road sports car from the early 1970s. Ford planned to use its Lincoln-Mercury distribution network to sell five thousand units a year – five thousand! Alejandro likely swooned at such a number, even fantasizing that he could hire Enzo Ferrari as his butler. But his hopes ended up dashed to bits. Because demand was never great enough. From 1971 to 1974, no more than six thousand vehicles were delivered to the US. Ford withdrew from the deal, but for a different reason: There were simply too many manufacturing defects. In Europe, De Tomaso sold no more than a few hundred units a year through his own dealers, but only until 1993, when the last model series was discontinued. The Pantera was certainly deserving of a more successful story. It is a unique creature, a red-hot fire-breathing Italo-American that sweeps you off your feet with lightning bolt dramatics.

So now a benevolent and generous person had parked such a De Tomaso Pantera in front of my door, namely a black 1972 (but since the early Panteras were supposedly not available in black, the car had most likely been repainted by one of the previous owners). The man with the car stressed that the Pantera meant an incredible amount to him, as it had grown on him like a wild animal that had been tamed and probably shouldn’t be released back into its natural environment. He pressed the key into my hand and said, “Do something beautiful with it.” I didn’t have the guts to look him in the eye. When I have the chance to borrow a dream car of this caliber, I started to say, and then prevaricated some more, it’s always one of those things. I said that I appreciated the trust he placed in me, of course, but even with the best of intentions I could not guarantee that the Pantera would come back in one piece. Only now did I venture another glance his way. His Adam’s apple twitched nervously. How was he to interpret my comment, he wanted to know. Well, I continued, especially with such a set of wheels as that, any tiny little thing could go wrong in the blink of an eye. Even a rally god like Walter Röhrl is no exception. And then I told him the story published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on April 5, 1993: “RALLY DRIVER RÖHRL SERIOUSLY INJURED IN ACCIDENT – The two-time rally world champion Walter Röhrl was seriously injured in a car accident on Saturday. The 46-year-old from Regensburg crashed his co-driver’s Ferrari F40 head-on into an oncoming vehicle on the road between Irlbach and Wenzenbach. The Italian sports car rolled over several times. Röhrl and his forty-one-year-old friend, the owner of the car, were barely able to escape before the car burst into flames.” I embellished the facts with a little background information that an insider had given me at the time: A rich Bavarian friend of Walter Röhrl’s had bought an F40 and thought to himself: “Awesome! My buddy Walter is a two-time rally champ. He’ll give me a lesson on how to wrestle this red devil into submission.” Of course, Walter didn’t have to be asked twice and rode the red devil all the way to the gates of hell. That’s where the story ends. No one knows how their friendship fared in the weeks following that infamous outing. The owner of the Pantera listened to me very attentively, and when I finally asked what would happen if I were to total the De Tomaso, he simply said, “Then I’ll kill you!” I admired his honesty. I mean, how often do you get the chance to climb into a black De Tomaso Pantera with a death threat hanging over your head?

At this point, I’d like to say a few words about Walter Röhrl: The small misstep with the F40 didn’t change the fact that, of all my racing heroes, he is the living legend who is the closest to me. Mr. Röhrl grazed my thigh with his Audi quattro during the World Rally Championship in Portugal in 1986. I was one of the many braindead fans standing behind a crest in the middle of the road and only got out of the way at the last minute (in the truest sense of the word). We wanted to make sure to get a close-up picture of the Group B monster. It came flying along with a roar and kicked up a lot of dust when it landed, which settled on my head. I didn’t wash my hair for two weeks out of religious reverence for the monster and its master. In case anyone is interested: I had come from Vienna by motorcycle, six thousand kilometers there and back in five days. Upon returning home, I was already in the preliminary stage of unconsciousness and was as stiff as a Senegalese wooden figure after sitting bent over on my Suzuki GSX-R 750.

You have to suffer to be fast. Which is doubly true if you’re driving a Pantera. The seating in this brutally beautiful car is very low and very uncomfortable (the best – oh yeah! – is the view from the back, those incredible, albeit not standard, 295 rubber wheels and the four tailpipes with the rear end perched over top). But those seats! Truly, they are perhaps the crappiest sport seats you’ve ever subjected your spine to. It’s like the seat surface doesn’t even exist, just the backrest with zero lateral support. Well, you’d better get used to it, because when we accept something, as we know, it loses its power over us. There is an alternative: brand-new racing shells with FIA type approval and brightly colored belts. The style equivalent of a record-scratch, but they certainly give the car that extra pop. Everything else, of course, must stay as-is. Let’s start with the steering wheel: no buttons or knobs. A steering wheel just for steering. No, you heard right, but just in case, this time in ALL CAPS: A STEERING WHEEL ONLY FOR STEERING. The young’uns are floored! Behind it, the speedometer and rpm counter, both analog. On the center console (arranged vertically) the additional indicators for battery charge, gasoline, water and oil. That’s all a supercar had to say to you in the seventies. It let you do your thing. It provided you with insane power and didn’t rein you in in any way. But there was something unspoken between the two of you, and every time you brought it to life and it started roaring and the cold shiver of fear ran down your wet back, you knew what it meant: You alone, after all, are to blame for getting too much lead out. And the only thing that can help you after you’ve pushed the envelope too far is a quick “Our Father” – but even that might be cutting it too close. Moving south from the center console, we discover the finest German workmanship: the ZF (Zahnradfabrik Friedrichshafen) five-speed transmission in the “dogleg” design, with first gear located down and to the left (which, if you squint real hard, is supposed to resemble a dog’s leg stretched out backwards). “Dogleg” style has the decisive advantage that you can get from second to third gear without having to switch shift gates. In the Pantera, you don’t want to waste too much time interrupting your traction. Down below, where the pedals are, it’s a tight squeeze. In the heat of the moment, you’ll have to be careful not to pump the gas when you actually want to step on the brake. Let’s conclude our in-depth look at the interior with the extremely exclusive white, black and blue patterned mats. featuring the branding mark of the de Tomaso family’s cattle farm, which doubles as the car factory’s logo. You’ll want to kick off your shoes and get down to business barefoot.

Let’s put it to the test: Ignition. The chorus of evil awakens. What a barbaric yawp! Crude and vulgar and unbridled and full of elemental juices – enhanced by the overtones of a jackhammer and underpinned with the sinister tonal quality of the large-volume V8. The Pantera screams at the top of its lungs. The furor emerges, as it were, from the depths of time, in mutiny against electronically generated engine noise. It gets under your skin and makes you part of its twisted game. In your mind you shout, “Down with the insanity of progress!” Cognitive affirmation comes from the words of Heimito von Doderer, an Austrian writer, not particularly known for his intellectual prowess, who was particularly receptive to technological progress. That’s probably true, you say to yourself, because as a would-be dialectician you will have furnished yourself with sufficient proof by asking the perpetual question: “Would you want to regulate the goddamn temperature of your goddamn refrigerator back home in the fourth district of Vienna via your cell phone while sitting at a bar on the Copacabana beach?” No, not YOU, brainiac! The old black panther and the old white male (only four years older) are a good match. We will get along swimmingly, and at the end of this auspicious day – I see it coming as clearly as a hangover after a drinking binge – we will part only in pain.

Someone once wrote that you need the arms of a bodybuilder to steer the De Tomaso Pantera. Anyone who says that is a weenie and a wimp, and maybe even an out-and-out wuss. I have roughly the arms of eighty-two-year-old Woody Allen (if that), and I still managed to get the car out of the parking spot. Admittedly, it was a tough job, and I don’t recall ever having wrestled with such recalcitrant and strength-sapping steering.

The eight-cylinder engine runs smoothly. When I stepped on the clutch, I thought, Oops, that’s the brake. But it was indeed the clutch, although the pedal gave my calf considerable resistance. First gear. Obediently, the engine picked up some steam. Tim, our boss’s son, and Matthias, who photographed this story, initially followed me from behind in a Volvo SUV. I flipped on the turn signal at the first gas station; I wanted the beast filled to the brim. Tim said, “There are flames shooting out of the exhaust. Mega cool.” Suddenly something snapped inside me. A jolt went through me. It was like getting shocked by an electric fence. Then it traveled to my right eye. The left one remained still but watered slightly. “Flames, you say, is that true?” – “Out of all the pipes. I know what I saw!” I was seized by a wave of indescribable bliss: flames shooting out the back! The flames – caused by overlapping valve timing common in high-powered engines, resulting from unburned fuel entering the exhaust when downshifting and igniting there – are, along with the roar, the hottest ingredient of a supercar. The highest visible escalation level. In truth, it’s the fire that makes it the consummate villain. (The last fire-breather I drove was the McLaren 600LT Spider. I saw its flames in the rearview mirror while doing 317 km/h. The car had an upward-pointing exhaust system. On winter days, when it’s already dark as a bear’s ass at five in the afternoon, the memory of the McLaren’s fire warms my soul).

We took some really beautiful pictures. Afterwards I said goodbye to my dear colleagues. I told them that I would not be back before sunset. Then I drove over the river and through the woods. The road was a tantalizing temptation, and the panther was stoking the flames of its anger. But it was full and solid and fat on the asphalt, so confidence filled me to overflowing. The transmission had a wide gear ratio. I was still only in third. It felt like I was going 250 km/h, because the forces were tugging at the steering wheel and noise insulation was rather meager fifty years ago, making it roar like crazy in the cockpit. I cut my speed but shifted up to fifth gear. Deliberately, I drove slower and slower until I was just crawling – in fifth gear, mind you, while keeping the car from jerking. Do that in a Ferrari! Then I downshifted (back to first gear) and kicked it. The Pantera (1,400 kilos and, according to the registration certificate, 345 hp) goes from zero to a hundred in about six seconds. In 1972 that was just below the speed of light. Today it’s almost an eternity. But its brutal nature again conveys a completely different feeling. It is not possible to go any faster, you think. Still, a troubling thought crept up on me: I hope I don’t run into a Hyundai i30 N Performance. That little rice maker would be hard to shake off. Only in the top speed range would you find peace of mind. The GPS, the Pantera owner told me, measured it at 270 km/h. He could not recommend driving at high speeds in the old, original chassis, however, which could be quite tricky. But he also said he felt the engine was itching to do more, and he was therefore considering “souping it up” with a second fuel pump and a larger carburetor.

A noble goal, but sweat was already beading on my forehead. The engine breathing down my neck turned up the interior temp to roasting. The air conditioning wasn’t working. I wouldn’t have turned it on anyway. I could have cracked the window without a second thought. But cooling air would have been tantamount to a criminal distortion of the facts. My candy bar was already threatening to liquefy, so I scarfed it down. I licked my paws, thinking it was now time to up the intensity for my test drive. And this meant that at the apex of the next turn, I hit the gas pedal with all of my ambition. The rear end did not break away abruptly (which I had suspected anyway) but moved outward in a well-controlled manner. By countersteering and pumping the gas pedal in the proper doses, I maintained a respectable drift that gave me a wonderful view of the road through the side window. There’s nothing like a sports car that good-naturedly oversteers. Braking, however, was a whole different ballgame. If there was anything resembling a pressure point at all, it was certainly late in coming. Humans are an adaptable species. Just hit the brakes earlier and that’s it. And yet I enjoyed drifting so much that I didn’t want to stop. They should put up “Caution Drifts Ahead!” signs here. By now the sweat was already pouring into my eyes. It must have been a hundred degrees in there. I was in my element. Lightning-fast driving in its purest, most honest form. Just the clutch and gearshift, with no power steering or electronic driver-assistance systems. Real blue-collar stuff – and above a certain speed it wasn’t necessarily easy to find the perfect timing. I felt fantastic. And I knew: Everything would be fine. I wasn’t going to end up a murder victim.

Postscript: Before I sent it to my editor, I sent this story, like many others, to my friend Michael Macho, son of the former general representative for Aston Martin, Bentley and Rolls-Royce in Austria. Michl knows cars (and not just English ones) like no one else. I like to have him fact-check my texts. This time he wrote me back: “Congratulations! This article is yet more proof of your incompetence! Because by claiming that the De Tomaso Pantera is a unique creature, an ardent Italo-American, you suggest that there has never been another Italian sports car with an American engine. Which is not true, of course. Ever hear of the Iso Grifo with the Chevy engine (later Ford)? Or of the Bizzarini, also with Chevy under the hood? Guess not. So I suggest you quit your job at ramp first thing tomorrow morning, take all your savings and drive around the world. According to my calculations, you should be back home around 2 pm. And then apply for a job at your local garden center.”

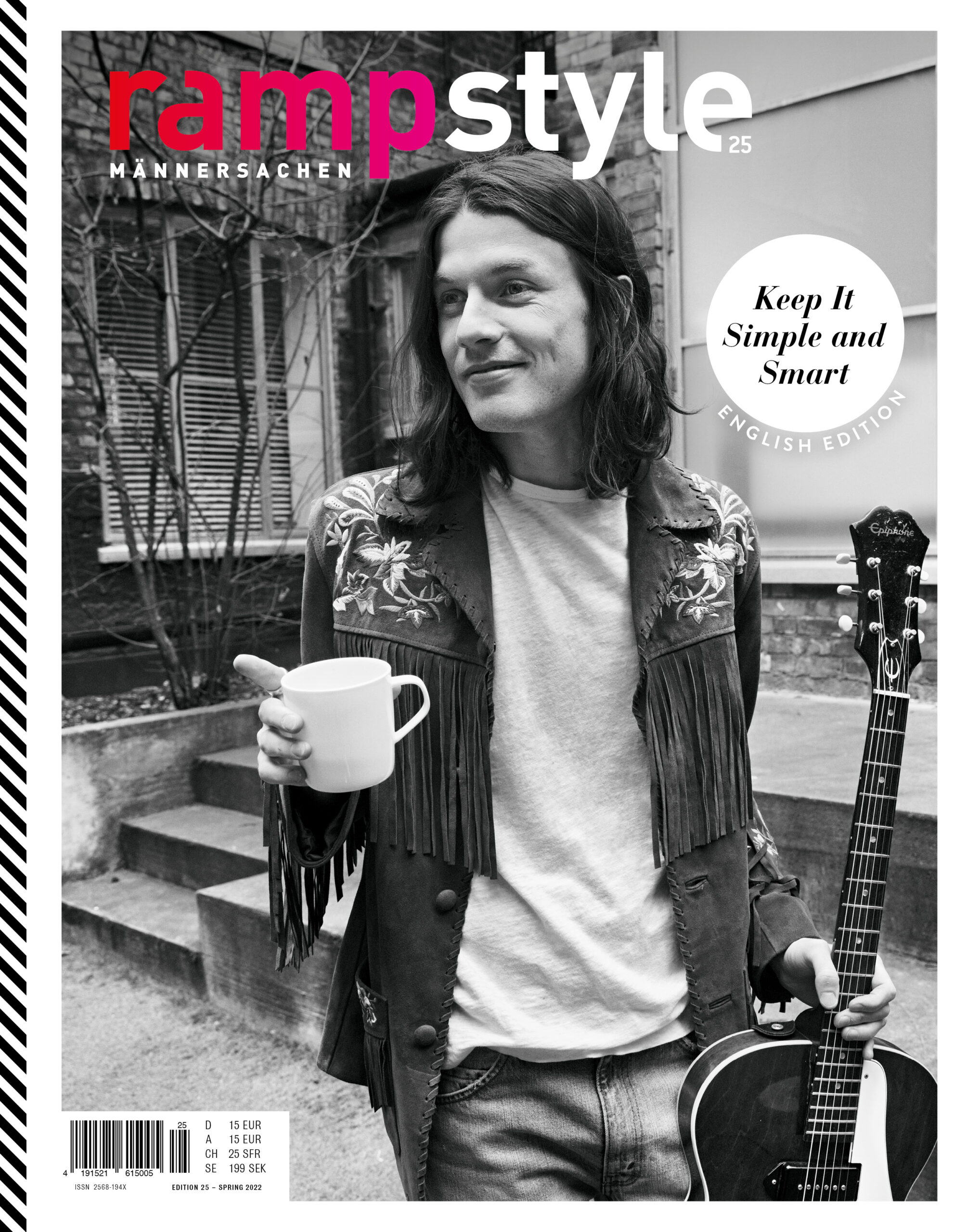

Read all about it in rampstyle #25, entitled “Keep It Simple and Smart”.

We tend to experience our world as not only somewhat complicated, but also extremely complex. And while complicated systems offer themselves to our understanding through clearly defined connections of individual elements, this unfortunately does not apply to complex systems. Here, everything is unpredictable. And there we are, more or less merrily in the middle of it all. Which is why we love minimalist solutions. In short, the KISS principle applies: “Keep it simple and smart.” An entire issue devoted to the matter. So we simply asked Bryan Adams if he wouldn’t like to photograph singer-songwriter James Bay exclusively for us as part of our interview with him. (He did.) We also have a great story about Tom Ford, interviews with George Clooney and the designer Sir Paul Smith, and we spoke with the director Quentin Tarantino and with author Christian Ankowitsch, who wrote a book titled “The Art of Finding Simple Solutions”. The conversation turned out to be more complicated than expected. But just as entertaining as we imagined.

Text by Kurt Molzer for ramp

Photos by Matthias Mederer/ ramp.pictures