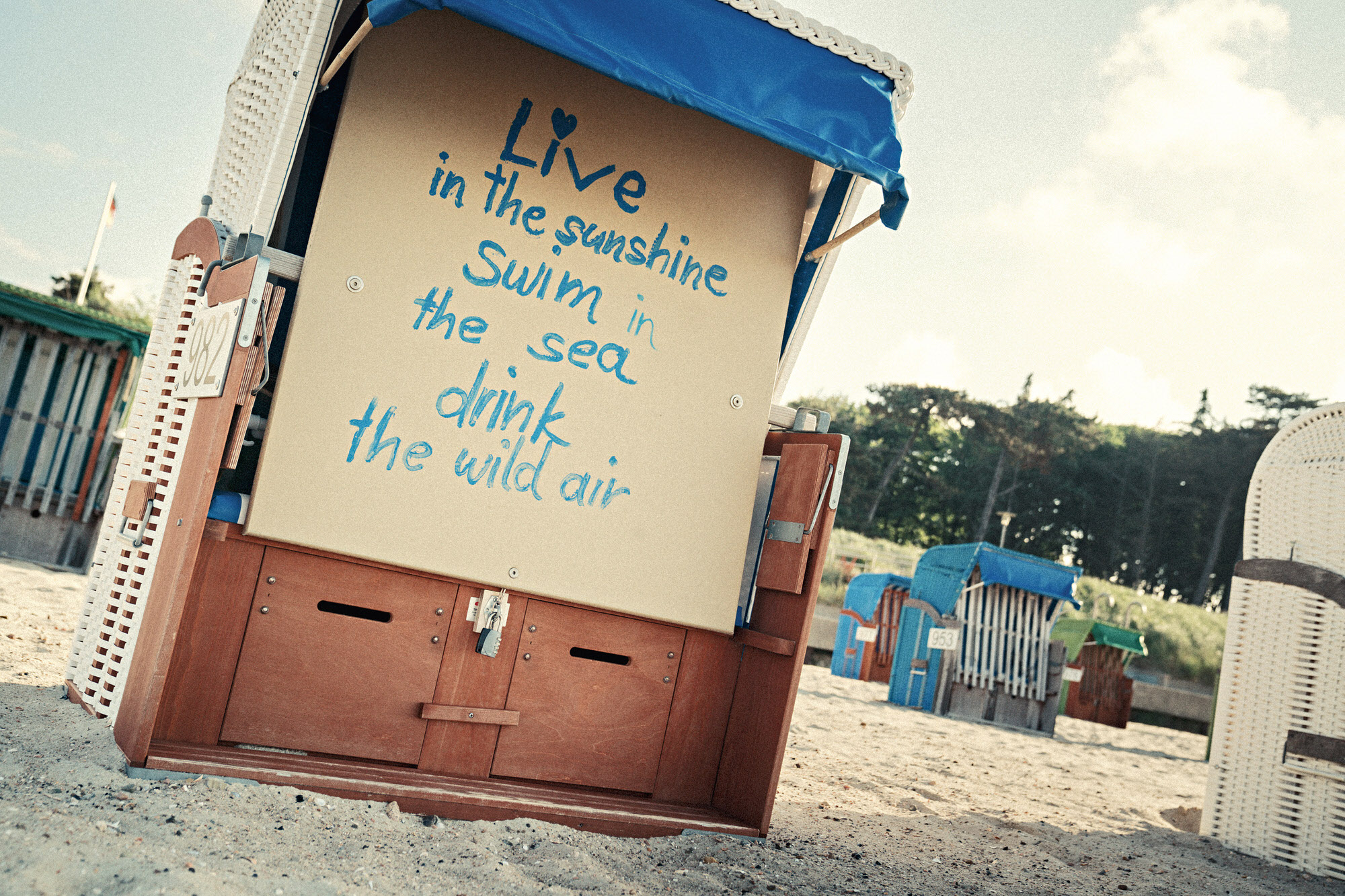

An island isn’t just a geographical entity, it is a metaphor for an idyllic retreat. A place where we can leave the relentless pace and overagitation of the hectic world wonderfully far behind.

And because a place like that lends itself so perfectly to stories of discovery and adventure, it was clear that we would have to wash up on those shores someday ourselves. The perfect island was soon identified, and the right car for the trip wasn’t hard to find either. And sometimes we could even see the sea.

While half of southern Germany was under water from all the rain, you could easily see the seabed from the ferry in the North Sea, that’s how thinly distributed the water was here during low tide. I wondered how the ferry managed to get from Dagebüll to Wyk at all. It was heavily loaded with cars, all of which looked bigger than the island in front of us. Ahead of us lay Föhr, a fairytale-like German backdrop, jutting out of the mudflats in all its beauty. Our goal: relax and unwind a bit before taking our Porsche Turbo for a spin.

On our little SSST trips for ramp, we sometimes end up in surprising and special places, I thought, watching as a huge patch of mud moved towards us. A group of children were romping through the mud next to the harbor, looking for lugworms, examining all the holes on this “largest unbroken system of intertidal sand and mud flats in the world”, as the Wadden Sea is described by UNESCO. A paradox. How can it be both a sea and a tidal flat? But after the ferry had made it all the way to the island with almost no water beneath its bow, I was no longer surprised. The mudflats are said to be home to thousands of different species of creatures, though the most famous is undoubtedly the invisible lugworm, or so the tourists told me. Young people, in particular, want to see it up close – though few of them do. Worm hunting is an attraction of its own on Föhr. The lugworm burrows itself into the mud, leaving behind a coiled cast of sand for the young people to see, prompting them to try and get the worm out of its hole with small shovels or simply with their fingers – more often than not to no avail. Just wasn’t meant to be, the young people then think, and off they go to the ice cream stand next to the oversized outdoor chess set to eat ice cream. The worm is used to being hunted, it can camouflage itself very well. Our test car, a light blue-gray Porsche, also looked well camouflaged on the shore of the Wadden Sea, with the mudflats and the sky over a similar light blue-gray hue.

Föhr to me seemed like a giant playground for grown-up children. Our car immediately stood out in the narrow streets. Are you even allowed to drive here? A few pedestrians registered their annoyance with us. Let’s just stay cool and give them a friendly smile, Michael, the editor-in-chief of ramp magazine said, sitting at the wheel as relaxed as ever. Leaving the nervous, excited and overagitated world far, far behind. That was our plan. That’s exactly why we hadn’t gone to the more fashionable island of Sylt, popular with celebrities and the loudly singing party crowd, but instead chose this self-confidently low-key island of more hushed tunes. Germany’s second largest North Sea island is a popular travel destination, with miles of sandy beaches and a maritime climate favored by the Gulf Stream that has earned it the nickname of “Frisian Caribbean”. Families and active holidaymakers love Föhr, explains Michael, who for many years looks forward to spending a few days or weeks on the island. Sylt is like Munich, Föhr is like Tübingen, he says cheerfully with a sly nod. As a Tübingen native, he should know. Boris Palmer, the (formerly Green) mayor of Tübingen, has probably been here more than once. Though probably not in a Porsche Turbo.

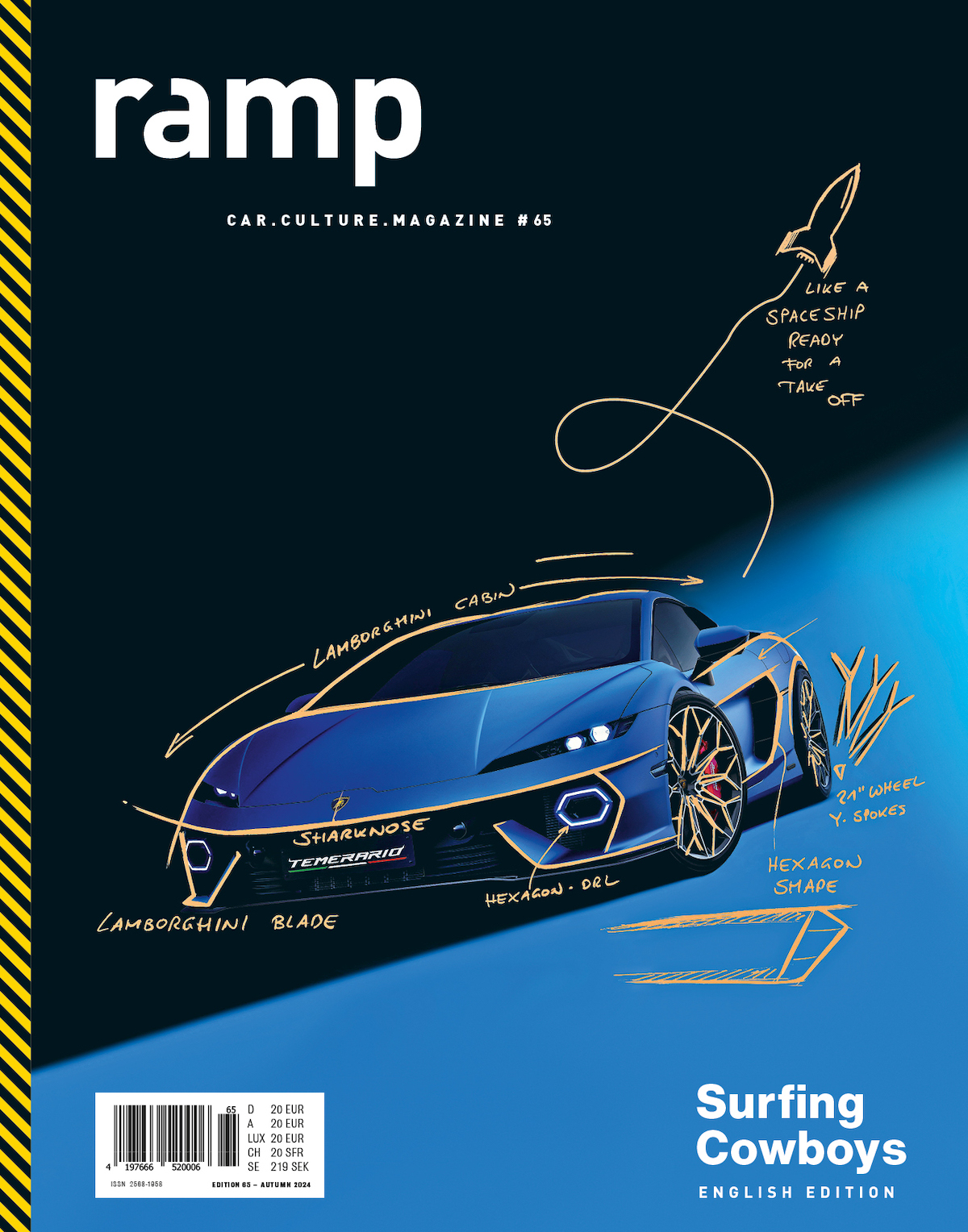

Michael had been on the road for over ten hours to get to Föhr from southern Germany, and he didn’t even look tired. He wasn’t driving the latest Porsche Turbo either but had taken the previous model. You don’t always have to swap what’s good for what’s new, says Michael. In academic circles they even have a word for this kind of addiction to the latest craze: neomania. The boffins tell us that we humans tend to reflexively overestimate the value of new things, which is why the phenomenon was immediately included in the category of cognitive biases as an aberration of thought. So Michael and I ignored everything new and happily drove a few rounds across the island.

With the ferry, we had left the turbulent civilization of the mainland on the other side of the sea. We now wanted to lean back and focus on the timeless substance of this planet – on the Wadden Sea, which changes beyond recognition every few hours, but always remains true to itself. We could see it from the terrace of our hotel, which bears the almost unpronounceable name of Upstalsboom. I couldn’t sit in the hotel for long. I regularly went out to the shore to take a close-up look at the sea, because, according to the tidal schedule, high tide was due at some point soon. I had heard from the other tourists that the water comes flowing back in when you turn your back to it. So I pretended not to face the sea and tried to spontaneously turn around. All in vain, the water didn’t come. Sometimes a little, but not everywhere. The ebb and flow of the tide is magic.

There is no watertight scientific explanation for this phenomenon. Some say that the gravitational pull of the moon is to blame, but the moon appears the same everywhere on the planet, so why should it attract the water here in the North Sea more than in other places? There are also those who say that the water in the North Sea is pumped out every eight hours, an old capitalist trick to attract tourists. In the neighboring, formerly socialist Baltic Sea, the water is available at all times, not much, but always in the same quantity for everyone. On Föhr, the water dances, it rocks back and forth, coming and going as it pleases.

I courageously broached the subject with a few local women. “What’s wrong with your sea?” I asked them. “The water is dancing back and forth! Is it already here or is it still gone?” “We don’t know why it’s dancing,” the local women answered. “We wondered at first too, but you get used to everything.”

But the water isn’t the only thing that is different here; the people, too, are of a special breed. They never really care what the weather is like. The weather doesn’t play a big role for the tourists either. People who come here are prepared to go for a walk even when it’s raining down hard and are willing to plunge themselves with all their might into cold water that barely reaches to their knees.

Niebüll, Dagebüll, Sankt Peter Ording – these place names to me sound like the names of rare animals that once roamed our planet until they were driven away by the spread of civilization and retreated to the Wadden Sea to lead a happy retired existence. What a unique place!

It’s not for nothing that the Wadden Sea was recognized as a World Heritage Site, and the Frisians themselves are a protected minority. You’re not allowed to push them or touch them without further ado. There are five different authorities responsible for each dune here, as a photographer who wanted to take pictures of the nearby dunes told me. He spent one whole month on the phone to the authorities to get the necessary permits. The code enforcement office was responsible for the area in front of the dune, the dyke authority was responsible for the area behind the dune, the administration of Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea National Park was responsible for the area on the dune itself, the State Office for Roads and Waterways was responsible for the dune access, the nature conservation authority was responsible for the birds on the dune, and the tourism authority was constantly trying to assert its jurisdiction as well. Whenever the photographer had clarified the situation with one authority, another would vehemently refuse to give its consent. After a week of difficult negotiations, the photographer discovered by chance that all these offices and authorities were located in the same building, that they even shared the same office space – and were sometimes even represented by the same person, who could speak in different tones of voice. That’s the Frisian sense of humor.

The protracted, tenacious struggle between nature and civilization has given rise to a previously unknown breed of people here, people who merrily ignore all trends and don’t need yoga to live a stress-free life.

Nature wanted everything here to stay the same, with summer and winter, ebb and flow. Of course, man initially had something else in mind, a dream of how things could be even better. He built dykes, took the land back from the sea and settled on the reclaimed soil. Nature tried again and again to wash it away – with varying degrees of success. North Frisia emerged from the discrepancy between what is and what could be. A crazy landscape where everything is mixed up. The aquatic plants live on dry ground here, while the plants in the local gardens are often up to their necks in water. More attention is paid to the dykes than the roads, and the sheep and ducks here look happier than the local people, as if they’d just won the lottery. In town, I went out for wine and fish in an authentic seafood place that only served plaice. “We celebrate plaice in its most beautiful form” was written on the advertising leaflet. So I joined in the celebration.

The North Frisian sun is inconspicuous but dangerous, and suddenly I had a sunburn on my face without even feeling it. Again and again it rained and clouds came up. In the center of town next to the harbor, a few tourists were trying their hand at outdoor chess. Though some of the pieces were missing. Or were there too many? Something was wrong. “Someone stole the rook last year – or maybe just took it home as a souvenir,” one of the locals lamented. “I don’t get it,” he sighed. “The rook is huge, it won’t fit in any suitcase. I certainly understand if someone wants to take a bathrobe or a bath towel from the hotel home to the mainland to give to their wife or lover or whoever. But the rook from an outdoor chess set?” Later, the queen disappeared in the same way, and the city council ordered all the figures to be replaced in the fall. After the winter, the queen suddenly reappeared, hidden in the snow, twenty meters away from the chessboard, probably carried off as prey by a large dog. Now the chess set has three queens and three rooks. “Only Bobby Fischer can play with that, but Bobby Fischer is dead,” the local lamented.

I only spent two days on Föhr. But for weeks afterwards, little grains of sand were still falling out of my pockets. And the fresh North Sea air, which smells of the sea, tastes of salt and tingles on the skin, lingered on in my mind.

Text by Wladimir Kaminer

Photos by Matthias Mederer · ramp.pictures

ramp #65 – Surfing Cowboys

If you think “Surfing Cowboys” refers to neoprene-clad prairie riders or surfers wearing cowboy hats, you’re slightly off the mark in this case. In the latest issue of our Car.Culture.Magazine, it’s about the meeting of two quintessentially American archetypes, both embodying a deep longing for lived independence and untamed, self-determined freedom. Find out more