We write about almost anything with wheels. A garbage truck has wheels. So we sent out one of our own to try his hand as a refuse collection operative. In Vienna. For a day.

Because always driving Porsches and Ferraris and Lamborghinis does end up being somewhat monotonous at some point.

Time: Half past five in the morning. Place: Johannesgasse 9–13, downtown Vienna. A low-rise in the courtyard of a 1950s residential building. The “accommodation” for the garbage men in Vienna’s first district. Though we shouldn’t say “garbage men”. Officially, they’re “refuse collection operatives”. Or “waste management professionals”. And we don’t say “garbage cans” either. They’re containers. Or bins. Good. Now that we’ve got that out of the way, we can proceed.

My day as a Vienna refuse collection operative starts at the “accommodation”. I’m in the changing room with Andi, Christian and Sami. Stripped down to our underpants. Andi, 52, not very tall, tattooed from the neck down. Christian, 57, ponytail, wiry, a sort of James Bond type. Sami, 32, Finnish parents, grew up in Vienna, upper arms that could tear out trees. A cheerful Finn who loves to laugh, not at all melancholic and depressed? The eighth wonder of the world!

Christian looks me up and down. “Soup-Kaspar, day four,” he says, referencing an old German children’s story about a boy who wouldn’t eat his soup. (Soup-Kaspar famously dies on day five, emaciated down to a mere stick figure. Don’t anybody say that garbage men aren’t well-read!) I defend myself against the insult. Say that I regularly lift weights, in the open air by the Danube Canal, on a specially erected steel scaffold. Calisthenics, I say, explaining that the word comes from the Greek word kállos for “beauty” and sthenos meaning “strength”. I tense my upper body: “Look, my chest muscles aren’t bad at all.” They all burst out laughing. “He calls those muscles,” says Andi, “And he’s not kidding.”

Andi asks me how many push-ups I can do. When he started working here, twenty-nine years ago, he had to do a stress test on a stationary bicycle followed by a series of push-ups. My record, I say, is fifty. Roaring laughter all around, nobody believes it. “Let’s see you do it!” says Christian. I get into position. Hands on the floor, shoulder-width apart. Head in line with the body. A nervous silence. I push myself up easily twenty times. Thirty times (would love to see their faces now). Forty. I hear someone say “Wow!” Then it gets tough. As if I had a pack full of bricks on my back. After the forty-sixth rep, I collapse, panting, my head bright red, and lie there in my blue and white checked boxer shorts like someone who’s been shot from behind. “Hey, you’re all right!” They accept me. Incidentally, new recruits still have to do the stress test on the exercycle followed by push-ups. Pulmonary function testing and body composition assessments are also required. If your percentage of body fat is too high, they advise you to take another job. How does butcher sound?

The bright orange work clothes are a perfect fit. On the jacket, at chest height and in curved handwriting like a brand logo: “Die 48er.” “The 48ers.” Because “48” is the number of the municipal department responsible for cleaning up the city. This has long been the colloquial name for Vienna’s refuse collectors, too. They, the “48ers” (starting salary: €2,800 a month before taxes), are the heroes of the Austrian capital, removing more than a hundred thousand tons of refuse from the city of two million people every day. Without them, the rats would rule (though let’s not forget the hard-working street sweepers!) The fact that Vienna is repeatedly voted the most livable city in the world (from the British Economist Group and US consulting firm Mercer) is in part thanks to them. Last year, the “48ers” were even awarded the 2023 Vienna Tourism Prize. Because the city’s cleanliness is the most frequently mentioned point in international travel forums. Let’s just come out and say it: Vienna has the best waste management in the world!

But how did I end up here? Well, it wasn’t easy. As I said, they don’t take just any random idiot who shows up, especially not for just one day. We had to deliver some good arguments. In a nutshell: We told them how great they are. And how great we are. And how great we would be together. In the end, there was no way they could say “no”. We also told them that the writer of these lines had no fear of coming in contact with garbage, indeed with dirt in general, which possibly has something to do with the dirty thoughts that are constantly running through his head. Anyway, that’s how I got the job.

“I’d say you’ve earned yourself a coffee,” says Andi. A whole bunch of his coworkers are sitting around a table in the lounge. “Who’s this guy?” one of them asks, lifting his chin in my direction. “That’s Kurt, he’s with us today, as a journalist close to the action,” Christian answers for me. “Here comes Kurt, not too long and not too short,” says a younger, fully bearded man. A poet. The coffee knocks my socks off and I immediately realize that this is no place for mama’s boys.

Six o’clock sharp: Andi, Christian, Sami and I leave the “accommodation” on foot. We divide into two teams: Two of us bring the full containers out of the houses onto the street. The other two bring the empty ones back. To keep things fair, the men swap roles every other day. “So which job do I do?” I ask. “You do both, that way you have more to write about,” says Sami. Though for the first half hour, all of us are in charge of the full bins. We have to bring as many of them out onto the street as possible – so when the truck (with another colleague, the “bin tipper”, on the running board) has plenty to swallow when it arrives from the “48er” headquarters in the fifth district. We use a central key to gain access to the buildings.

If there aren’t any stairs to climb, we take the most common 240-liter containers two at a time. You roll one in front and pull the other one behind you. Weight isn’t the problem; the important thing is coordination and not swerving too much. The front bin pulls to the left, so I hold against it, which forces the rear one to change direction as well. That isn’t without consequences for my wrist and forearm. It also makes me move in serpentine lines like a drunk.

In Krugerstraße, a porter kindly holds the door to the inner courtyard open for me. She’s probably in her mid-forties, smoking a cigarette and has a rather lascivious look on her face. “I don’t know you,” she starts. “I’m new, ma’am,” I say. She watches me as I awkwardly pull out an overflowing container from the far corner. The top bag tumbles out onto the ground. “I can see that,” she remarks. I go to pick up the bag, but she beats me to it. “How long is your trial period?” she asks, blowing out a puff of smoke. I make a thoughtful face: “Lifelong, I’m afraid!” – “Lookee here,” she says, “A philosopher taking out the trash!”

My colleagues and I go from one house to the next. At one point, they’re far ahead of me. I hurry after them. A police car drives past. The officer behind the wheel rolls down his window and shouts: “Good morning!” Am I dreaming? Why is a policeman greeting me? And in such a good mood, like the moderator on a television morning show? Me of all people? If only he knew. I’m so taken aback that I don’t return the greeting. The police and me go way back – our relationship fills entire file cabinets. I just have to get the following story off my chest: In my better years, I would drive a different sports car every two weeks for testing purposes. I was constantly getting pulled over, in Austria and in Germany, mainly by unmarked cars on the autobahn, even if I wasn’t exceeding the speed limit. One of them once said to me with absolutely no shame (I was driving a Mercedes SLR McLaren on the A8 in Bavaria): “We only stopped you because we wanted to take a closer look at the car. You don’t see something like that every day.” – “Okay by me,” I said, “but I’m not going to put up with this any longer.” I took revenge by writing a story with the headline “The Cops Make Me Want to Throw Up.” The text was full of insults of the crudest kind. Of course, they sued me. I took it in stride. At least I had gotten it off my chest. The case ended up before the Munich district court. A journalist from the serious Süddeutsche Zeitung and a few others from the more sensationalist papers were sitting in the courtroom to report on my case. The judge wanted to slap me with a fine of six thousand euros. I feigned a nervous breakdown and said I was no longer working as editor-in-chief (which was the truth), but as a line cook in a café-restaurant (the biggest lie of my life). The good woman actually bought it. She took pity on me and reduced the amount to eight hundred euros. I never paid. My place of residence was in Austria, and they couldn’t get a hold of me. By now the statute of limitations has long expired. Back to the present: I ask my new friends from the refuse collection service if they know why this policeman might have greeted me. The answer is prompt: people who work on the street greet each other, and that also goes for parking attendants, bus drivers, ambulance drivers and so on. (I hope no parking sheriff greets me, otherwise I would have to tell the next story. Just this much: I ended up in a holding cell for seventy-eight hours.)

Christian and I walk back the way we came (the other two continue on in the opposite direction). The garbage truck has now arrived and the tipper has emptied the first containers. We take them back into the buildings we brought them out from. One of my destinations is the garbage room behind an Irish pub. To get there, I have to pass through a narrow corridor. The floor is full of kitchen grease and as smooth as glass. I slip, fall on my back and land hard on my butt and elbows. The two empty garbage cans (wrong terminology, I know, but I don’t feel like always writing about containers or bins, it’s been irritating me the whole time, because I think of containers as being something for jam and not garbage) topple over and crash into the wall. A noise as if half the stairwell were collapsing. The back door of the pub opens. A petite Filipina – presumably the cleaning lady, because she’s holding a broom – sticks her head out: “Everything okay?” Refuse collector Molzer scrambles to his feet, ignores the pain and sticks out his thumb: “No problems here!”

Sweat is pouring out of every pore, and that with an outside temperature of seven degrees Celsius. I’m constantly on the move. Andi tells me later that he clocks thirty thousand steps per working day. The tipper guy also lets me do his job from time to time. It’s a cinch. You put the bins on the tipper, press the lever and boom. We’re all back together, heading from the city center towards Mariahilfer Straße, Austria’s biggest shopping street. I want to get on the running board and breathe in the cold air. They tell me I can’t for insurance reasons (“If you fall off, we’ve got problems.”) Fine, at least that way I can talk to the driver, Walter, 42. You can tell he has the cushiest job of the whole bunch: a round face and a real gourmet bulge under his shirt. It looks as natural on him as the twenty-eight-inch waist on Mick Jagger. “Do the other guys like you at all?” – “Why shouldn’t they?” – “Because you just sit here and drive and they all work their asses off.” – “They’re fitness fanatics.” – “Who earns more?” – “It’s about the same, ha ha ha!”

I’m just waiting for an impatient driver to honk his horn because he has to take the kids to school, then make a quick dash to his mistress before heading to the office. Doesn’t happen once. “By now people have understood that there’s no point. And besides, it’s their garbage that we’re taking away,” says Andi, explaining the exemplary, disciplined behavior of the other road users in their cars.

Ten past ten. Break time at the “accommodation”. Walter drives the garbage truck filled with nine tons of waste to the incinerator facility. We’ve bought ourselves something to eat at the supermarket. I ravenously devour a chicken schnitzel roll with ketchup and mayo. Wash it down with a Coke. Chase it all with pack of Schwedenbomben, a chocolate-coated marshmallow treat, first the ones sprinkled with coconut flakes. I need them as consolation and as medicine, my butt and elbows really hurt. No one saw the fall. I didn’t say a word. Because I want to look good. I want them to say, “Kurt, you’d make a great garbage man.” Because there’s no future in journalism. Journalism is in as bad a state as Porsche was about thirty years ago when they were on the verge of closing down shop in Zuffenhausen. The difference is that journalism – good, quality journalism – will never survive. It’s over. Somewhere, every day, another journalist is being laid off. Nobody reads newspapers anymore. Even the old people at the café stare mindlessly into their smartphones. Would I even like being a garbage man? I think back to a recent chance meeting with my dear colleague David Staretz. We bumped into each other on Berggasse in Vienna, just opposite the Sigmund Freud Museum. (I was coming from pull-up training and David has his office around the corner.) It wasn’t long before we were talking about the decline of our industry. We would have loved to lie down on Freud’s couch (which, unfortunately, is in London). David said, “Crime scene cleaner, now there’s a job with a future.” People who remove traces of blood and other gruesome things after a crime. A surefire job, so to speak, and not many people want to do it. I’d still rather be a refuse collector than a crime scene cleaner, garbage doesn’t stink that bad even in the worst summer heat. David and I then went to a second-hand clothing store, where I bought a fabulous knee-length winter coat for twenty-five euros. Back at the “accommodation”, my waste management colleagues don’t say “Kurt, you’d make a great refuse collector”, but “Kurt, could you get some coffee, please?”

Walter picks us up again at eleven. We head for the sixth district: Linke Wienzeile and Naschmarkt. Lots of 1,100-liter containers. One of those is better than two of the 240-liter bins. The big ones you just push along in the front of you, there’s nothing to it. The longer the day goes on, the more I enjoy it. Because I feel like I can keep up and my coordination is getting better all the time. I’ve just tipped a container into the truck and am walking to the next building. The way there takes me past Nautilus, an excellent fish restaurant. Because I have my suspicions, I peek through the window. I knew it: My son is there at his favorite restaurant having lunch (he obviously has nothing else to do), four friends are sitting at his table. All incredibly young, all incredibly good-looking, all incredibly successful. Just you wait, I think to myself! I go in wearing my “48er” outfit and shout loudly from the entrance, “Hey, Bela, what are you doing here?” His face turns as red as an Afghan poppy field. All the guests turn around. I approach the table, which is overflowing with seafood. “Gentlemen,” I say, “How’s your meal?” Without being asked, I reach into my son’s plate and take an oyster. I slurp loudly, the juice running a little from the corners of my mouth. “Hi, Dad,” says Bela in an embarrassed whisper, “What’s with the get-up?” His friends stare at me and stifle a laugh. “My work clothes, first day, wanted to surprise you. Aren’t you proud of your old man?” – “It really is very surprising,” is all he says in reply. I tell him that I have to get on with it, otherwise my colleagues will kick me in the ass, times have changed. I’m done at two, I’ll call him then. Knock on the table on my way out: “Gentleman, a pleasure.” As I’m leaving, I hear one of his friends say, “You always told us your dad writes for a cool magazine and drives the wickedest cars.”

Text: Kurt Molzer

Photos: Oliver Gast

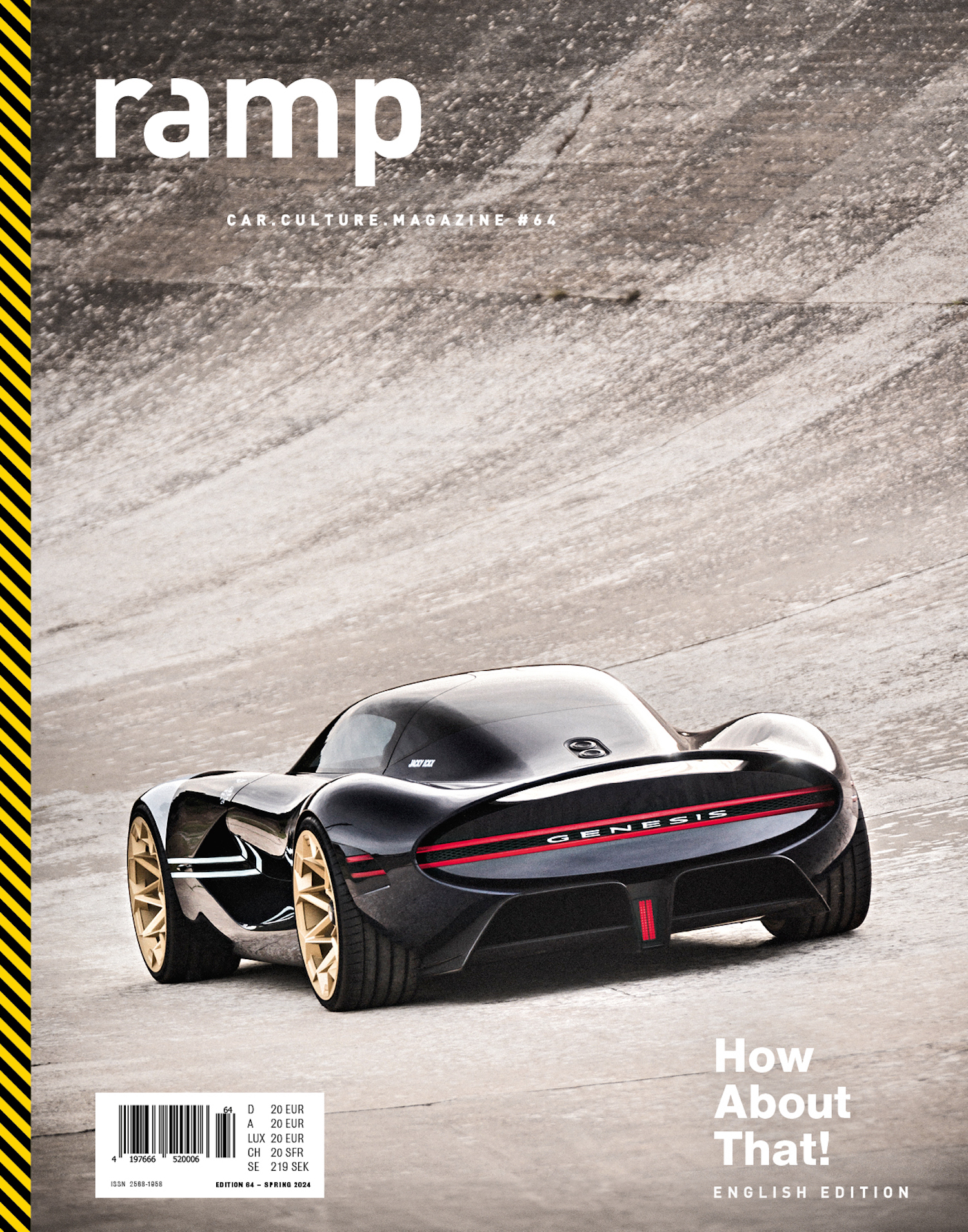

ramp #64 How About That!

Surprises open our eyes to new things, which now isn’t really a big surprise. The unexpected simply stays in memory longer, sparks curiosity – and prompts action. Essential for adapting to a changing world. The future might just be warming up for progress. It’s meant to move forward effectively. Find out more