Car enthusiasts who came of age in the ’80s or ’90s regard Lotus as a bonafide manufacturer of exotic cars, the names of which can be uttered in the same sentence as a Porsche 911 or whichever mid-engined V-8 Ferrari was then current. This was not accidental, nor was that always the case, and the Esprit is almost singlehandedly responsible for this conception of the marque.

But Lotus was in a very different place before the Esprit came out—by the early ’70s, a significant disconnect had developed within Lotus Cars. In the world’s most prestigious races, Lotus Formula 1 cars were a force to be reckoned with: Lotus won its first Formula 1 World Championship in 1963, just 11 years after Colin Chapman founded the company, and by 1970, the brand had four F1 championships to its name.

The company’s road cars, however, did not enjoy the same levels of success and prestige. Lotus had only made a handful of roadgoing models by this point, each of which had a four-cylinder engine displacing at most 1.6 liters, and some were offered in partially assembled kit form for enterprising enthusiasts on a budget to complete themselves.

The down-market associations of kit cars did not do justice to either the on-track performance or the underlying technical content of the cars Lotus was creating. After all, Colin Chapman built Lotus on the philosophy of innovation—pioneering a whole host of groundbreaking technologies such as monocoque construction, composite bodywork, mid-engined racing and road cars, the Chapman strut, and downforce in racing cars, initially with wings and later ground effects. To more effectively position Lotus’ road cars as accurate reflections of the prestige and sophistication of the marque, Chapman initiated the development of three new cars for the 1970s, of which the Esprit was one.

Despite the dissonance between the road and race models, the growth and success of Lotus had been particularly meteoric during the 1960s. The company moved into the brand-new, state-of-the-art Hethel factory (where their headquarters remain to this day) in 1966, the company went public in 1968, and of course, there were all those race wins. While it was appropriate in the company’s early years to focus on selling road cars to the die-hard motorsport enthusiasts who were willing to tolerate sliding windows (or fixed windows, or sometimes no windows at all) and cramped quarters, it would be necessary to make cars with more mainstream appeal for Lotus to continue to grow.

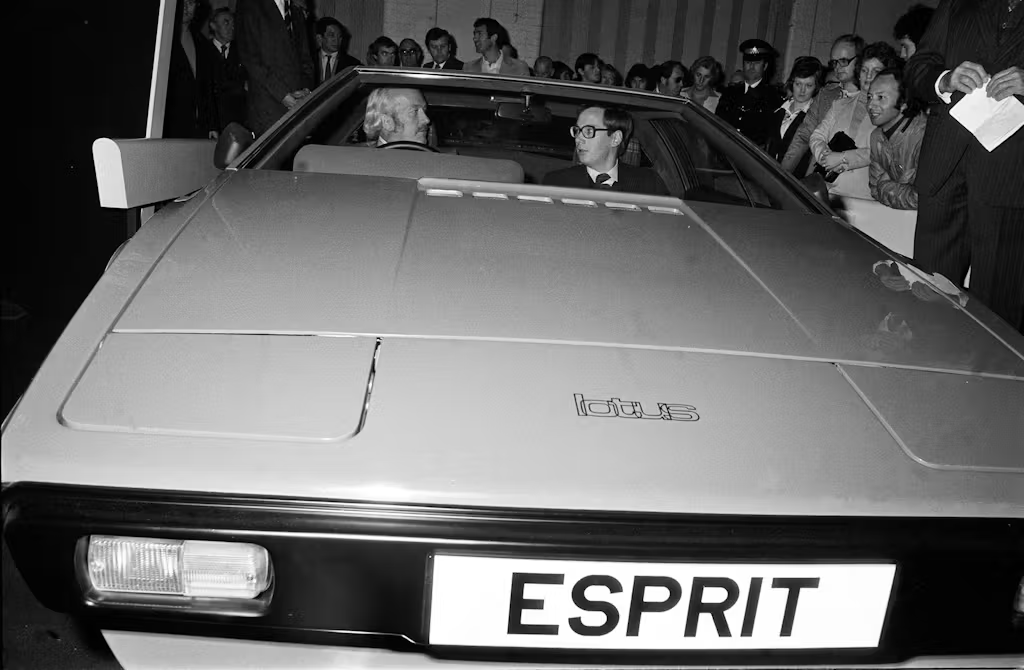

The resulting cars were the Elite, Eclat, and the Esprit. The Elite and Eclat were both front-engined and were effectively identical from the B-pillar forward, with the Elite having a shooting-brake-style rear treatment and the Eclat a fastback arrangement. The Esprit, on the other hand, was mid-engined and received arresting wedgy styling produced not in-house like the other two cars, but by Italdesign, the firm of legendary designer Giorgietto Giugiaro.

All three cars were powered by a new Lotus-designed alloy 2.0-liter twin-cam 16-valve inline-four. This was the first engine Lotus designed in-house, despite the existence of the prior “Lotus Twin Cam” engine which was actually derived from a Ford unit. Designated the Type 907, the new engine was first used not in a Lotus, but in the Jensen-Healey sports car, where it was rife with problems that eventually earned that car a poor reputation and equally poor sales. Lotus largely worked out the problems before the 907 appeared in any of their own cars, and the engine became one of the best parts of the new Lotuses, revving to 7000 rpm and introducing four-valve heads to production cars about a decade before the units from rival engineering powerhouses such as Porsche, Mercedes, Ferrari, or Lamborghini.

The Esprit chassis was typical Lotus, featuring a backbone arrangement with triangular structures at each end to which the suspension was mounted. The rear also housed the powertrain. It was an enlarged version of the concept that underpinned their first mid-engined road car, the somewhat peculiar-looking Europa, which bowed a few months after the Lamborghini Miura.

A central part of remaking Lotus’ image was to give the Esprit world-class looks to draw in buyers who based their purchase decisions on more than just the car’s technical minutiae. Lotus Designer Oliver Winterbottom styled the two front-engined cars but understood that it would take a maestro to give the Esprit the contemporary look he sought, and thus arranged a meeting between Colin Chapman and Giorgietto Giugiaro at the 1971 Turin Motor Show. The meeting occurred at the Italdesign stand, and it was agreed that a year later at the 1972 Turin Motor Show, the new Lotus would be debut in concept form.

Lotus obtained an apartment in Turin and began weekly flights (often piloted by Chapman himself in the company plane) between England and Italy as the teams worked feverishly to develop the Esprit. The resulting concept did appear on time and was largely representative of the production article, despite being made of metal, rather than the fiberglass of the production cars.

The Esprit was developed in a skunkworks fashion, with the car’s engineering being sequestered from the main Lotus facility up the road at Ketteringham Hall. While the engine, chassis, and styling parts of the Esprit were coming along nicely, late nights were common to solve several as-yet unanswered questions, such as which transmission to use. Lotus Engineering Director Tony Rudd observed, “we had yet to get thinking about that.” Ultimately, they went with the five-speed unit from the Citroen SM, which Citroen thankfully left in production for many years after the SM was discontinued.

A pre-production prototype Esprit debuted in 1974, and following delays caused by corporate financial issues, production of the Esprit finally began in 1976. The car was well-received by both the media and the buying public, although most of the public met the car not in magazines but on the silver screen. Always seeking maximum impact for the dollar, Lotus learned that a new James Bond film would be filming at Pinewood Studios, and PR boss Donovan McLaughlan gave the doorman a pound to park an Esprit where executives would see it as they came and went. The stunt worked, and the car was written into the script of The Spy Who Loved Me, where the submersible Esprit would become one of the most recognizable movie cars of all time.

Mr. Bond went on drive a pair of turbocharged Esprits in 1981’s For Your Eyes Only, and Esprits featured prominently in Pretty Woman and Basic Instinct a decade later. And so Mr. Chapman’s dreams were realized convincingly. The Esprit had the sizzle for Lotus to cross the chasm from appealing to fringe sports car enthusiasts to mainstream covetability.

Of course, the Esprit was made for more than show, and it had the moves one would expect for a car produced by a company that, at the time, had won more F1 championships than anyone else except Ferrari. The core Lotus values of a superb chassis, sophisticated powertrain, and light weight are all in evidence. Coming in at 2200 pounds and 160 horsepower, the Series 1 Esprit’s power-to-weight ratio is nearly identical to that of an early Porsche Boxster. Power is delivered in a very linear fashion, with a high-revving character that is very different from the long-stroke inline-fours of other British sports cars like Triumphs, MGs, and Austin-Healeys. The gearchange is slick, precise, and mechanical, and the synchromesh effective and quick in its operation. The chassis is well-balanced and chuckable, but also offers exceptional ride comfort, something which magazines noted even in period when taller sidewalls were the norm on sports cars. As a result, the car is a pleasure to hustle on a tight, bumpy backroad—the type of road that is ideal for a Miata or a hot hatch suits the Esprit perfectly as well.

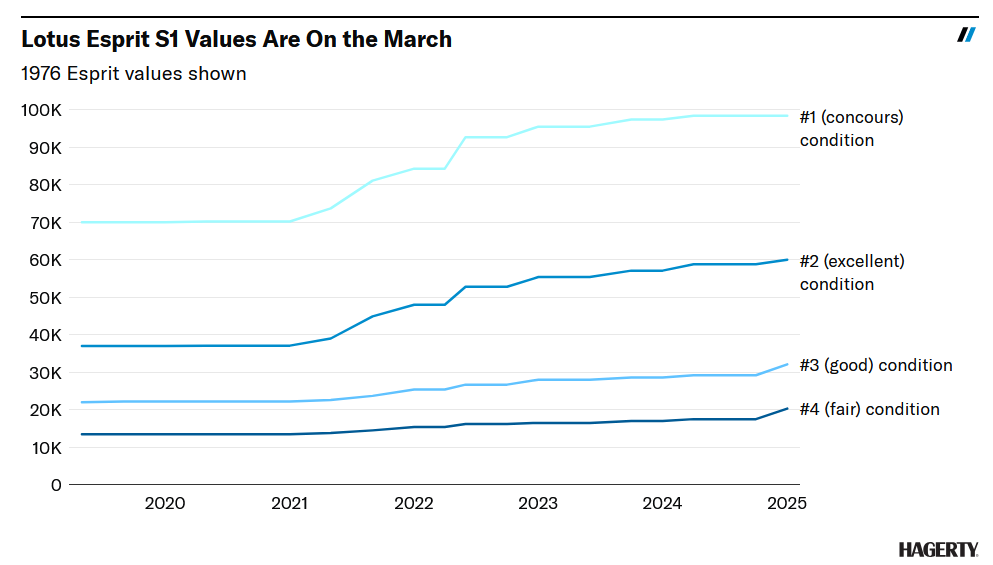

The Esprit remained in production for a remarkable 28 years, and over 10,000 were sold. The model was developed continuously, with turbocharging being offered for the first time in 1980, and the V-8 variant finally arriving for 1996 (it had been foreseen during the car’s development in the 70s), which offered performance that almost perfectly matched that of a 993 Turbo or F355. Exterior styling was redone by Peter Stevens for 1988 and freshened periodically. Until recently, all Esprits were inexpensive to buy, and today, most of them remain inexpensive. However, when truly exceptional, they do break into six figures. Typically, this territory is reserved for V-8s, but a few early cars have touched these figures, including a 19,000-mile example—sold by my firm, OTS & Co.—that had received a $105,000 mechanical restoration but retained original paint and interior, which sold for $163,500 including fees on Bring a Trailer last month.

By and large, however, it’s possible to buy an exceedingly nice early Esprit for under $75,000, with perfectly pleasant examples coming in around half that, especially of less desirable variants. They are, however, old British cars, and thus require specialist attention, making them more difficult to live with than a Porsche, or even a Ferrari. But it is telling to mention the Esprit in the same sentence as these other two sports car legends and so in that sense, the Esprit did exactly what Colin Chapman wanted it to do when he initiated its development.

Report by Derek Tam-Scott

find more news here.