Richard Harman remembers the first time he heard the name Briggs Cunningham. It was in working-class West Bromwich, England, in the early 1950s. Harman was a small boy cozied up to the wireless, listening to the hourly updates from the 24 Hours of Le Mans on Radio France because, back then, he says, the BBC didn’t do updates every hour. The French commentator was yammering live from a trackside booth, “and every time that Cunningham would come around, he would shout, ‘Écoute!’ and stick his microphone out the window so you could hear it.”

Harman smiled, for a second floating serenely in the memory of a 331 Hemi bellowing at full-bore over the shortwave and into his living room. “It sounded like nothing else.”

Crossing back over the years, Harman was with us again in 2018, standing on a seaside lawn in blue-blood Greenwich, Connecticut, where people were milling around highly waxed classics as a considerably more mellow Benny Goodman wafted from the sound system. Except for two, every surviving example of the 35 cars that Briggs Cunningham built for racing or for customers was gathered there. Made possible by a few local Cunningham disciples plus our own Barn Find Hunter, Tom Cotter, who owns a barn-found Cunningham himself, the Briggs Cunningham reunion at the Greenwich Concours was an exhibition of commitment that rivals any of the glittering goat ropes that Pebble Beach has ever assembled (well, OK, that one time with all the Ford GT40s—just, wow).

We spent the previous day motoring around in a Cunningham C3 convertible to some of Briggs’s old Connecticut haunts and then whiled away the evening watching flickering home movies from Le Mans and Sebring and listening to experts hold forth on the man as well as the legend. It’s been a spread-eagle belly flop into the deep Cunningham cult, and the learning curve has been steep.

The story in a nutshell: Briggs Swift Cunningham, Jr., was the yacht-racing heir of a huge “soap and suds” fortune. In 1950, he became the first American since the ’20s to field cars at Le Mans, entering a box-stock Cadillac coupe and a Cadillac-powered wedge that looked like a parade float. It was so hideous that the French dubbed it “le Monstre.” Cunningham got thoroughly drubbed—and also completely hooked. The next year he built a couple of Hemi-powered specials to run in France as well as in some of the new road races around America. Then, yielding to European racing rules, he built 25 expensive Italian-bodied road cars in a factory in Florida just so he could compete at Le Mans as a manufacturer. Although the factory became too costly to keep going, Briggs continued racing in Jaguars, Corvettes, Oscas, and Coopers, and whatever else looked fast and ass-kicking until, after funneling a considerable quantity of his family’s fortune into a racing dynasty, he retired to California to tend to his immaculate collection of historic racing and road cars.

I confess I didn’t know any of this before this weekend. But once upon a time people knew all about Briggs Cunningham in Salina, Kansas, in Great Falls, Montana, in San Bernardino, California, and in Montgomery, Alabama. In those and hundreds of other small towns and big cities, Cunningham’s name appeared regularly in local newspapers that mostly don’t exist anymore, a fixture in the Associated Press auto-racing blurb that once shared the sports pages with the duckpin bowling scores, the daily racing form, and the profiles of lady wrestlers.

Back in the day, newspapermen called him the “gentleman sportsman” and the “wealthy speed pilot.” He was “the tall and tanned yachtsman” who captained the 12-meter Columbia in the 1958 America’s Cup, and he was “the bridesmaid” for his repeated second-place finishes behind the wheel at Watkins Glen. The newspapers reported the minute details of his exploits in “the French grind” at Le Mans, naming him the leader of “the brave little band of millionaires who carry America’s sports car hopes abroad.” Cunningham’s face once graced the cover of Time magazine, and Esquire rhapsodized about the aristocrat who recklessly poured his own money into a factory to build cars for other aristocrats. But it was the local newspapers that made Americans care about the white roadsters with the blue stripes that went wheel to wheel with the Europeans, about races in the swampy Florida hinterlands and the pastoral New York Finger Lakes and in far-off France, where the wail of “the high-whining Ferraris” contrasted so distinctly with “the whiskey-voiced Cunningham.”

In 2003, just as Richard Harman was retiring from his job as a structural engineer building large tunnels, he saw Briggs Cunningham’s obituary in a magazine. Cunningham had been living in Southern California for several decades, overseeing his personal auto museum and doing the odd magazine interview. Harman then entered what he calls “10 years of absolute hell” to produce a two-volume, 844-page book on the cars and life of a man he had never met. Because, he says simply, “nobody had done it before.” Harman is not even a Cunningham owner; he’s into Alfas, a 1980s GTV6 gracing his business card. But like a lot of people, and men especially, he’s magnetized by the story of this American patrician who lived in a time when the world was bigger and still rife with feats as yet undone.

“Cunningham is not the modern version of the millionaire sportsman,” remarked Associated Press reporter Will Grimsley, covering the America’s Cup matches in 1958. “He is no playboy. He is married and the father of grown children. He doesn’t drink or smoke. Friends say he often retires at 9 p.m. With his relentless drive, he must. Where else would he get the energy?”

At least some of that old Briggs energy was required to pull together a Cunningham gathering last summer, as Chuck Schoendorf, a retired commercial insurance broker who owns three Cunninghams, told me. A few Briggsians gathered in Schoendorf’s kitchen the night before the pre-concours tour in which most of the Cunninghams planned to participate. Luckily, the original 35 surviving cars—of 36 built—still reside in the U.S. (although there are some respected replicas in Europe), a testament to the distinctly American appeal of Cunningham’s story.

Schoendorf and Cotter had organized a previous partial reunion in 2013, and, according to Schoendorf, “You could say we started this over a year in advance, or you could say five years in advance. Or you could say it all started 12 years earlier when I acquired my first C3, became obsessed by Cunningham cars, and traveled all over the place to meet owners and see and photograph their cars to help build mine. I also began tracking all the cars and their owners.”

But convincing folks to entrust what has become a million-dollar artifact from America’s motoring heritage to a trucking company for the ride to Greenwich, all at the owners’ expense, proved to require Kissinger-level talents of persuasion and gentle arm-twisting. Only a week before the event, the last stubborn holdout finally capitulated when Schoendorf offered to pass the hat to pay for the shipping. The owner eventually sent the car and even covered the bill.

After an all-night downpour, sunrise revealed a steamy, humid June morning for the tour with more rain threatened later. Schoendorf was gleefully perched behind the giant wheel of his two-tone tan-and-green C3 coupe, while his friend and mechanic, Don Breslauer, piloted Schoendorf’s C4RK coupe. It’s a replica of the only enclosed race car that Cunningham entered at Le Mans, in 1952, a weird and wavy sculpture speckled with scoops and knifed through with innumerable louvers. The cockpit is a tight-fitting bunker that must have been hot and deafening down the Mulsanne Straight, and it was a DNF after several mechanical problems and an off-course excursion. The original lives at the Revs Institute in Naples, Florida, along with a number of other significant Cunninghams, but it was deemed too fragile to move for the event. It is one of the two original Cunningham cars not present this weekend, the other being a C3 convertible that was rebodied years ago into a race-car replica.

A couple dozen Cunninghams plus some other cars once owned or driven by Cunningham filed out of the parking lot onto a twisting, undulating route that would take the Briggsians to various locales that were important in Cunningham’s Connecticut life. The family fortune was actually made in Cincinnati, where the senior Briggs Swift Cunningham went first into the meat packing business and then became an early director and investor in Procter & Gamble as well as various banks and railroads. The Cincinnati Enquirer noted in December 1912 that the passing of “one of the best-known wealthy men of this city” left behind a weighty fortune of $4 million plus $700,000 in real estate to his widow and two children, Mary and five-year-old Briggs Junior. After the Cunninghams decamped for highbrow Connecticut, the Cincinnati papers continued to twitter over their comings and goings in the society pages for decades.

Schoendorf kindly lent me his 1952 C3 convertible for the tour, one of only five convertibles built along with 20 coupes at the B.S. Cunningham factory at 1402 Elizabeth Avenue in West Palm Beach during the five short years it was in operation. The car is pure glam, the original two-tone, red-over-slate body echoed by the likewise two-tone interior with its giant red dials, battery of chrome knobs, and raunchy magenta-tinted glass sunshades. Compared with the mainstream cars of the early Eisenhower era, a Cunningham is a swingin’ go-go lounge, a bombastic mix of European flamboyance and American overkill for nightclub owners, Hollywood gossip makers, and other dedicated show-offs.

The Cunningham’s body design, complete with its oval grille and stainless-steel hood filigree, was a hand-me-down from Italian coachbuilder Vignale. Penned by storied Ferrari stylist Giovanni Michelotti, it appeared first and in nearly identical form on versions of the little Ferrari 212 that helped launch the house of Enzo in the early days. Vignale merely inflated the dimensions to cover the Cunningham’s much girthier chassis and Chrysler FirePower V-8. Compared with the massive Cunningham, the considerably more valuable Ferrari looks like a harbor dinghy.

Like most Cunninghams, Schoendorf’s C3 convertible was originally fitted with a Chrysler Fluid-Matic semi automatic, but likely in the 1950s, it had a Packard three-speed manual and Borg-Warner overdrive fitted to its 220-hp Hemi, the chromed column shifter moving in a big languid arc as the driver changes gears. We were rolling along in style through narrow tree-shaded lanes and past colonial-era farmhouses, the Hemi rumbling passively under the long hood. Along with the shoebox Fords and Chevy Fleetlines of that era, you sit as on an empire sofa, stepping down on the pedals, the big wheel heavy and somewhat lazy in your hands. Nothing is power assisted, and the drum brakes are good only by the standards of 1952. At a stop, Colin Comer came over to ask how I liked driving “the world’s nicest dump truck.” A former C3 coupe owner himself, Comer and his wife were manning his ex-Cunningham Lister-Jaguar. It’s a lumpy two-seat racing scull that Briggs campaigned in 1958, after he quit building his own cars, and he described it as “not a very fast car… does about 145 or 150 mph.”

After a while, a couple of screws vibrated out of our Cunningham’s shifter and it refused to go into first gear. Repairing that plus getting lost meant we got separated from the rest of the tour, so we continued on our own, stopping in at the 98-year-old Pequot Yacht Club, from which Cunningham sailed in 1958 to embarrass the British challenger, the 12-meter sloop Sceptre, four wins to zero. It was so many years ago, and on our visit it was so much quieter at the simple pink-brick clubhouse with its broad veranda overlooking Southport Harbor. Although photographer Amy Shore and I searched high and low, we couldn’t find any mention of Cunningham except on the inscription of one slightly tarnished old cup in the rows of the cabinets.

Disappointed, we moved on to Cunningham’s workshop at 93 Beachside Avenue in the Greens Farm neighborhood of nearby Westport. Briggs came by the property with his first marriage to the socially matched Lucie Bedford, whose family had been partners with a certain oilman named John Davison Rockefeller. Together they occupied the palatial estate fronting Long Island Sound across the street. Here again, the place was deserted, so we helped ourselves to copious photography of the C3 parked next to the low red-brick structure where Briggs once housed his pet cars. Later we learned that others on the tour attempting the same shots were run off by a groundskeeper.

That night, luminous Briggsians such as Miles C. Collier, director of the Revs Institute and descendant of Briggs’s old racing pals Sam Collier and Miles Collier, Sr., ascended the stage of the Greenwich Public Library auditorium to speak of the romance of the man whose employees affectionately called “Mr. C.” Going far beyond his family ties, Collier’s passion makes him extremely quotable on the subject:

“Here’s a single guy up against all the factories, operating 5000 miles away, having to do it all out of his wallet. And his motivations were the purest. There was nothing in it for Briggs, nobody was giving him any money, there were no endorsements, no contracts. If he did it, he did it purely for the sport and for the prestige of America, like defending the America’s Cup. He was really the last of the Corinthian sportsmen.”

As Time magazine reported in April 1954, that year’s Le Mans effort involved six drivers, 20 crewmen, two racing cars, and a mobile machine-shop trailer. The whole lot was loaded on the R.M.S. Mauretania for the transAtlantic journey, except for Cunningham himself, who flew over in time to meet the ship at the French port of Le Havre. The team then convoyed in the cars and the tractor-trailer over the roads to Le Mans, there to stay for several weeks. When asked what it all cost, Briggs’s standard answer was, “I have no idea.”

Esquire’s writer at the time heard that developing the roadgoing C3 soaked up $200,000 before the first unit was built, “and the possibility of profit is small since people who can afford approximately $10,000 for a car of this type are comparatively few. But profit is about as important to Briggs as rubber boots are to the enhancement of Marlene Dietrich’s legs.”

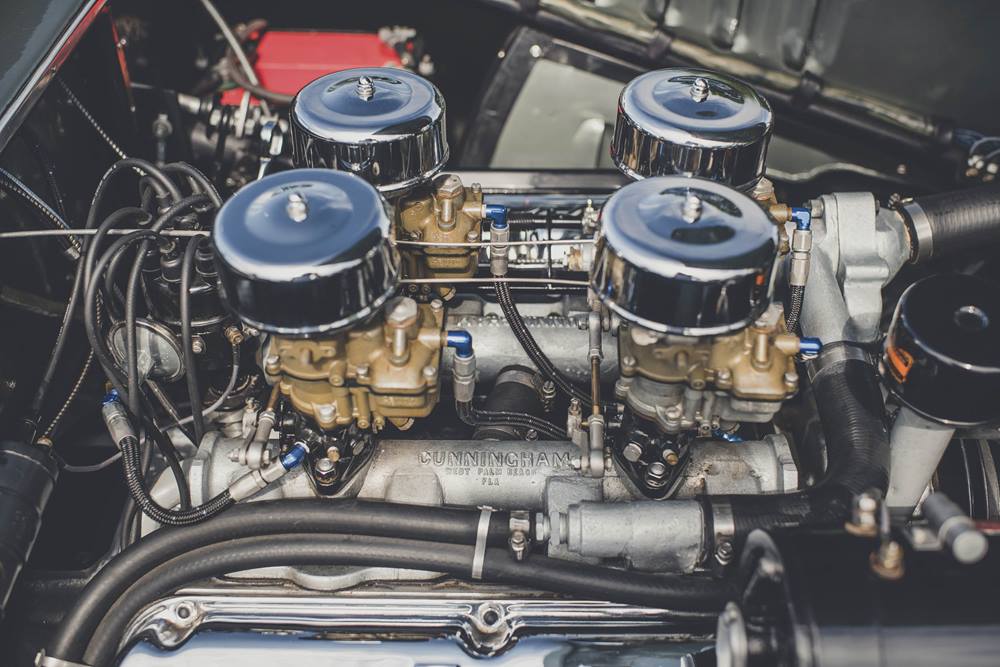

It’s a wonderful story of a man with limitless means spending dough in ways we’d like to think we all would if we had it. But I’m struggling with why it matters in the grand scheme of America’s motoring century. Until Tom Cotter, wearing a knee-length fur coat once owned by Briggs Cunningham himself, framed it for the library audience: “You have to understand, he was helping invent the American speed industry.” When Cunningham started in the early 1950s, there were few companies making speed parts for American cars. No disc brakes, no exhaust headers, no camshafts, no carburetors, no speed shifters, no nothing. Cunningham wanted to put a four-carb manifold on the Hemi, so he had to cast his own. Cunningham painted his cars white with blue racing stripes back when Carroll Shelby was still learning to steer into skids. Nobody had seen a racing stripe on an American car before.

Cunningham wasn’t just a rich dilettante pissing away money on the mother of all hobbies. Cunningham made racing and sports cars and speed parts matter to a nation that, but for a few early pioneers on the desert dry lakes, was satisfied that the 1951 Hudson Hornet was a high-performance machine. He was present at the creation of American road racing and was instrumental in its move from treacherous public roads to air force runways to permanent circuits. Everything that came after, from the Ford GT40 to the Pontiac GTO to the Corvette ZR1 to the Dodge Challenger SRT Hellcat, owes something to Briggs Cunningham.

The next morning, Cotter drove his flaky, weather-beaten, barn-find Cunningham C3 coupe onto the lawn at Greenwich and parked with the rest of the cars, a pair of lock-jaw pliers clamping the brake line to one leaky drum and that sumptuous old fur coat draped over the hood. Some owners say they love their cars because of the backstory, the wealthy gentleman of another age who was known to pass the off-hours at Le Mans by sweeping the garage floors or doing other menial busywork. Some because it offers genuine Michelotti styling on bodies that took Vignale two months each to handcraft, but marries them with a storied American V-8 that you can buy parts for at NAPA. Then there was the big-time collector from Pennsylvania who told me, “I dunno why I like it. I just see things and I buy them.”

Cunningham never did fully slay the Europeans with his cars. The best years were 1953 and 1954, when a Cunningham won the Sebring 12 Hours and took back-to-back third places at Le Mans. Cunningham himself finished fourth at the “French grind” in 1953. In late 1955, just after automobile racing was upended by the murderous crash at Le Mans, Cunningham closed and sold the West Palm Beach factory, telling the Palm Beach Post that “it just got to the point where we couldn’t build what we wanted with what was available in this country. We couldn’t compete on even terms. The foreign builders just outstripped us.”

That was true. It was also true that the IRS had allowed Briggs five years to turn B.S. Cunningham into a profitable enterprise, and those five years were done, so the business was now classified as a hobby and no longer tax-deductible. And it was, by all accounts, nowhere near profitable, even though there were plans to make another 25 cars, and even some chassis were constructed for it. Says Collier, “I think [chief engineer] Phil Walters was basically blowing in his ear and saying, ‘Briggs, if we do this right, we can probably defray a considerable amount of your racing expenses by selling these roadgoing cars.’ And that turned out to be a total fantasy.”

But the racing didn’t stop, as the various Jaguars, Maseratis, and Corvettes at the end of the line at the Greenwich Concours testified. Briggs Cunningham hated to be idle, and if he couldn’t build cars, he would buy the cars of others and keep going. “Sometimes I get in a car and drive to Chicago and back, just for the ride,” he once said. “I like driving that much.” And he kept right on going until he was finally flagged off in 2003 at the age of 96.

The Briggsians like to say that his motivations were pure, that they were for the sake of good sport and for upholding American honor on foreign shores. But Cunningham, talking to a reporter before sailing out to face Sceptre in the America’s Cup, probably put it best himself: “Some people like to do things with their minds. Some like to create, some like to build. I like to do things with my hands and feet. I like the feel of power in my touch.”

Report by Aaron Robinson for hagerty.com

Photos by Amy Shore