One hundred years ago, the world got its first BMW-badged motorcycle: the R32, the company’s first production motorcycle with a boxer engine. A perfect occasion to reflect on the past and look ahead to the future.

On this journey of reflection, one thing becomes crystal clear: to be authentically cool, you just have to do your own thing.

Two cylinders in the airstream. The symmetrical design is perhaps the most harmonious form of the internal combustion engine. Robust, compact, smooth, efficient. No wonder that the principle of the boxer engine seems unbeatable. The first motorcycle with this type of engine was presented at the Berlin Motor Show in September 1923. “And finally, the pinnacle of the exhibition, the new motorcycle from BMW with cylinders arranged transversely to the direction of travel. Despite its youth, a remarkably fast and successful motorcycle,” as a journalist for Der Motorwagen magazine wrote at the time. The engine, which was developed by German engineer Max Friz, had a displacement of 498 cc, produced 8.5 horses of power and accelerated the motorbike up to a speed of 100 km/h. The letter R, in case anyone was wondering, stands for Rad (German for “wheel”) – to distinguish the motorcycle engine from the aircraft engines the company had produced previously. What nobody suspected at the time is that the R32 would establish a design principle that is still valid today. So congratulations are in order. (In part because the author of these lines has been an enthusiastic owner of a BMW motorcycle for decades. But more on that later.)

It would be a bit simplistic to say that BMW motorcycles are so successful only because they have a boxer engine. After all, the Tucker Torpedo, of which only fifty-one were built before the company went bankrupt, also had one – though this is of course quite a bizarre example and not a very convincing one at that. So what has been so convincing about the motorcycles from BMW for the past one hundred years? The short answer is: they combine technological reliability with the human sense of adventure. An advertisement from the 1930s gets to the heart of the matter: “The proven and reliable BMW design can stand up to any challenge, leaving you with a reassuring feeling of absolute safety at all times with twice the driving pleasure.” This thought is formulated a little more elegantly (and politically no longer entirely correct) in an American advertisement from 1965: “If you want to be happy for a day, drink. If you want to be happy for a year, marry. If you want to be happy for a lifetime, ride a BMW.”

Which brings us to the heart of BMW’s historical archives, leafing through the decades and the technical innovations and sporting feats that have contributed to the company’s success over the past century. Let’s briefly summarize the beginnings: The name BMW stands for Bayerische Motoren Werke (“Bavarian Motor Works”), and while 1916 is usually regarded as the year of the company’s foundation, its origins actually date back to Rapp Motorenwerke GmbH, which had been manufacturing aircraft engines since 1913. In 1922 the financier and aviation pioneer Camillo Castiglioni bought the BMW company name and took over engine construction. The R32 was presented one year later. The time certainly was right: In the 1920s, the motorcycle became a popular form of transportation in everyday life. Between 1921 and 1924, the number of motorcycles in Germany tripled to nearly 100,000. To put that into perspective: at the same time, there were only about 130,000 cars on German roads.

The R37, launched in 1925 with 500 cc and 16 hp, already had twice the power of its predecessor. And while we’re on the subject of power and speed, this seems like a good place to mention BMW’s first world record: On September 19, 1929, Ernst Henne, nicknamed “Fast Henne”, rode his BMW WR 750 at 216 km/h, beating the world speed record in force at the time by 10 km/h. Eight years later, on November 28, 1937, Henne set a new record on a fully faired 500 cc supercharged BMW with a power output of 108 hp. Clocked at 279.5 km/h, this made Henne the fastest man on two wheels for the next fourteen years. Also worth mentioning, of course, are all the technical innovations of the era. In 1934 BMW introduced the first production motorcycle with a hydraulically damped telescopic front fork, and two years later the Bavarians gave us the first production motorcycle with footrests and foot levers for gears.

The Second World War marks a break in the company’s history. Following Germany’s capitulation, BMW was limited to building bicycles until 1948, when the American military administration allowed the manufacturer to produce its first post-war motorcycle: the single-cylinder R24 with four-speed gearbox. Although it sold like hot cakes, BMW continued to operate in the red for several years thereafter, and even a sale to Daimler-Benz was under discussion. The company finally started turning a profit again in the early 1960s, and in 1969 a new chapter commenced for the motorcycle division. For one thing, motorcycle production was relocated from Munich to Berlin; for another, the /5 series came along, a new design of the boxer model with double-loop tubular frame, rear swingarm and telescopic fork at the front, three-phase alternator, battery ignition, electric starter and vacuum throttle carburetor. The BMW R50/5, which made the start, was followed by the even more successful models R60/5 and R75/5. For the first time, other colors such as silver, blue or red became available in addition to black and white (these were used by the police with the curious nickname “White Mouse”). In 1976 the R100RS ushered in another new era in motorcycle construction. It was the first motorcycle manufactured in series to be fitted with a full fairing against wind and rain, a feature that was developed in the wind tunnel. Then, in 1980, BMW introduced not only the single-sided swingarm but also launched a motorcycle that was to become one of the best-selling models in the world: the dual-purpose GS. Derided by some as a two-wheeled Golf, lauded by others as nothing short of a legend, the GS saved BMW from financial ruin. 2003 saw the launch of the R1200GS, followed two years later by the R1200GS Adventure, which has since become the world’s best-selling motorcycle in the 600-cc-plus category.

Naturally, we should also mention that BMW was the world’s first manufacturer to include an electro-hydraulic anti-lock braking system in one of its motorcycles, in the spring of 1988, which was followed up in 1991 with the first three-way catalytic converter. There are two important events in BMW’s history, however, that have not been recorded in the company chronicles: this author’s motorcycle, a BMW R60/5, was built in 1970 – and she purchased it in 1990. (Over the years, it has been supplemented with a few parts from the /7 series, but let’s not dwell on the details here.)

In all fairness, it must be said that BMW’s motorcycles used to be seen as extremely uncool. In the nineties, everyone was buying Hondas, Kawasakis, Suzukis and Yamahas – and wouldn’t have been caught dead riding a Gummikuh (“rubber cow”). That was the common insult for BMW motorcycles back then, so called because the interaction of the Cardan shaft drive with the rear swingarm during acceleration often caused the rear suspension to lift up a bit. In contrast to the mostly high-legged, plastic-laden competition of the time, a twenty-year-old BMW R60/5, with its shiny chrome exhaust pipes and hand-drawn white double pinstripe on tank and mudguards, was a real relic. But it did have one decisive advantage: time was on its side. First off, there was the long history of the company that had designed it. That made it more robust than all the other motorbikes, with a low-wear Cardan shaft drive and an indestructible boxer engine. And it had a future. While everyone else was always taking their machines in for repair or suddenly found them to be out of date, the BMW kept on going. It has lived long enough to experience how people are no longer surprised to see a woman rider. Or that models from the same series suddenly appeared on the streets that had been altered and converted. The trend of customizing was born, and the motorcycles from BMW were a favorite object of interest. Then, in 2013, BMW presented the R nineT, a classic-looking bike fitted with modern technology that convinced even the last holdouts who hadn’t paid the Bavarian manufacturer too much attention before. The image of the brand had changed. BMW had become cool.

So now BMW Motorrad is turning a hundred, and the manufacturer is celebrating with the anniversary editions R nineT 100 Years and R 18 100 Years. Both are limited to 1,923 units each, and both celebrate the past with their double-pinstriping and chrome parts. And the author’s bike? Here to stay. Indestructible, always a little against the flow, always a little faster than you’d expect. That’s life with a BMW.

Text: Wiebke Brauer

Photos: BMW Motorrad

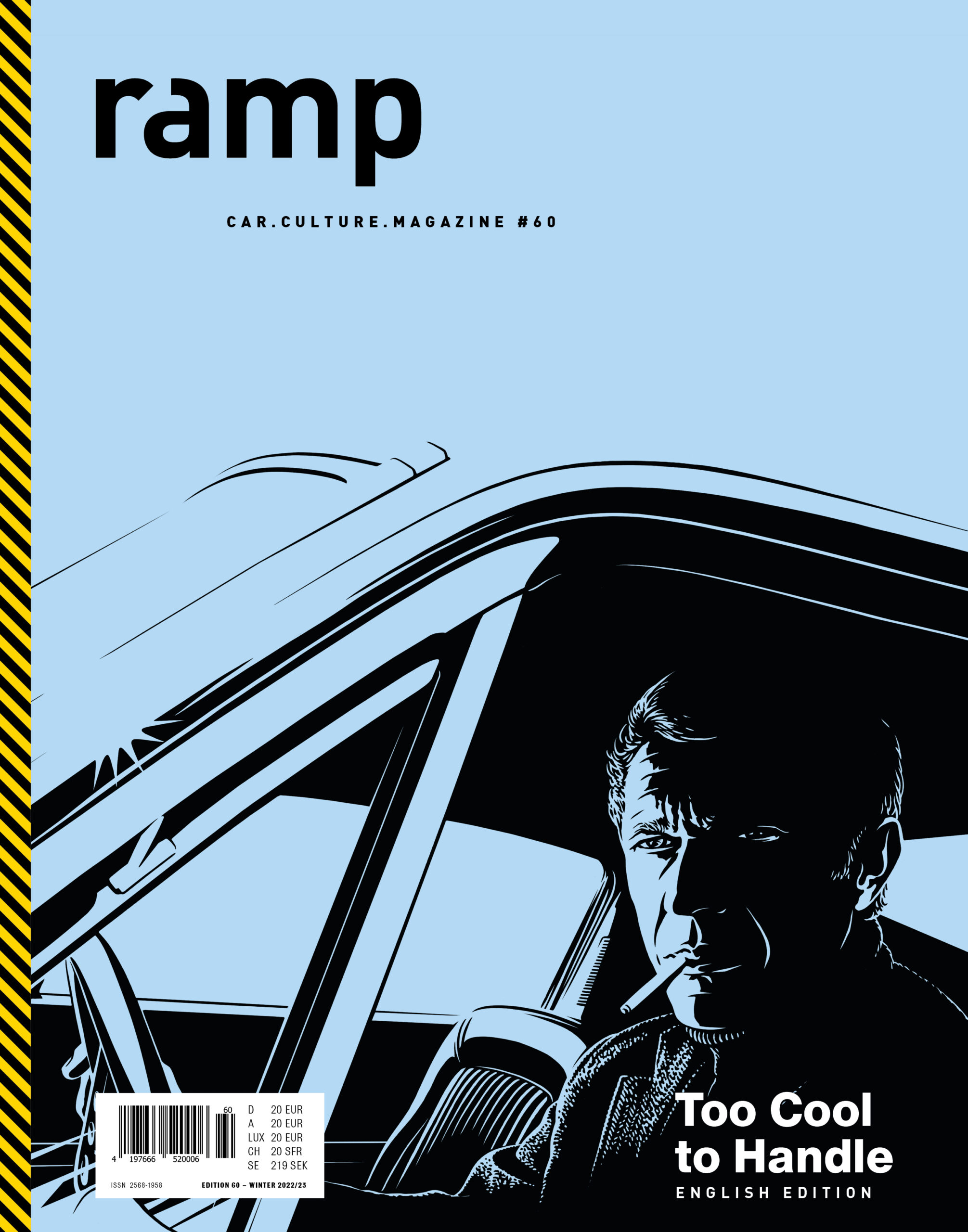

ramp #60 – Too Cool to Handle

As a high-impact multimedia brand that takes an all-encompassing, end-to-end approach to publishing, ramp is an absolutely authentic expression of quality, integrity and excellence. Its trailblazing luxury magazines, recognized with numerous awards over the past 15 years, have been celebrated for their cool and unconventional, not to mention inspiring and pioneering style, since day one.

ramp, the lavish and beautifully designed coffee table magazine, celebrates the enthusiasm for cars and driving in a passionately subjective, personalized fashion.

Immediate, authentic, intense. Fresh perspectives, avant-garde

A magazine about coolness? Among other things. But one thing at a time. First of all, it’s off to the movies. There’s this businessman from Boston who helps relieve a bank of a substantial amount of money. The insurance companies are on to him, but they can’t prove a thing. That, in a nutshell, is the plot of the film classic in which Steve McQueen plays Thomas Crown, who remains a mystery to the viewer throughout the entire film and who the actor plays with incredible composure, exuding absolute coolness at every moment. The German title of the film – Thomas Crown ist nicht zu fassen – hides a wonderful play on words, by the way. It could mean: Thomas Crown is unbelievable. Or it could mean: Thomas Crown cannot be caught. Cannot be seized. Cannot be grasped hold of. He’s just too cool to handle. Much in the same way, coolness also eludes our attempts to grasp it. A fundamental vagueness shrouds this fascinating phenomenon of longing and desire.

We’re fascinated by the irrational, the incomprehensible, the unbelievable. That’s why we also enjoy breaking the rules. We are living contradictions, as neuroscientists and psychologists so dryly explain. Our irrationality, innovation research tells us, is the secret to our creativity. It is our irrationality which insists that it is not we who must adapt to the world, but that it is the world that must adapt to us. This is another reason why any kind of progress depends to a large extent on our irrationality.

“If people never did silly things, nothing intelligent would ever get done,” the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once so aptly said. The physicist Richard Feynman opens our eyes to another aspect in this regard: “Physics is like sex,” he explains. “Sure, it may give some practical results, but that’s not why we do it.” And that’s just about how it was with this issue of ramp. Sort of.

With this in mind, enjoy!

Text & Photos: Marko Knab · ramp.pictures