The F355 rolled off the assembly line in Maranello thirty years ago this year. It was the best V8 that Ferrari ever made. A birthday tribute.

It has to have been one of the most shameful moments in the life of Luca Cordero di Montezemolo. The year was 1989. A red traffic light in Italy. Luca, a handsome man who always looked spruce and smartly dressed, is at the wheel of a yellow Ferrari 348 with Testarossa-style gills. Next to him is some kind of Abarth-tuned Fiat. First row on the starting grid, if you like. The aristocratic “Nobile dei Marchesi di Montezemolo” (the most noble Marquess of Montezemolo) usually doesn’t engage in duels of speed within city limits, preferring to leave that up to the rabble. But this time his right foot is itching and twitching (he’s only human after all), and he wants to teach the plebe a lesson. He’s got the Ferrari in first gear and is ready to go. But when the light turns green, the unspeakable happens: the Fiat makes the Ferrari eat dust! South of the Brenner Pass, this is called blasphemy. If the Inquisition had still existed, the guy in the Fiat would have been burned at the stake.

For Montezemolo, the world was turned on its head. As if sheep were suddenly eating wolves. He may even have thought to himself that the two letters “MO” on his license plate didn’t stand for Modena, but for Moscow. Monte, as he was known, then manager of the organizing committee for the World Cup in Italy, was made chairman of Ferrari two years later. He asked his old friend Niki Lauda to test the 348 (Montezemolo had been Ferrari’s racing director and won the Formula 1 championship with Lauda in 1975 and 1977). The Austrian driver did him this favor, returning the car with the comment: “Makes funny noises and drives jerkily.” In other words: a clunker.

Largely inspired by Lauda’s remarks, Montezemolo would later get a bit carried away, saying that the 348 was the worst Ferrari ever built. That makes me want to spontaneously say two things and pose an interesting question. Comment number one: You don’t want to have been the engineer in charge, do you? Comment number two: My deepest sympathy to anyone who bought one of those jalopies. And last but not least: Did Ferrari offer to pay the therapy sessions for those poor bastards who saved half a lifetime or more to buy themselves a 348?

They had a lot to make up for in Maranello. You can bet that those heads that didn’t roll were on fire from morning to night. I can just see that mercurial bundle of energy Montezemolo drumming everyone together, the man for the engine, the man for the gearbox, the man for the chassis and so on – all of them men, nothing has changed since then, just try a little harder, ladies, it can’t be that difficult to design a decent supercar engine in the twenty-first century – and how, gesticulating wildly, he impresses upon them that the successor to the bumbling 348 must make amends with the disappointed Ferraristi and show the world that the Via Abetone Inferiore No. 4 is still the first place to go for the ultimate sports car. Or did they really want to become the laughing stock for their dearest enemies in Zuffenhausen?

It helped. Ferrari brilliantly turned the rudder around. What came onto the market in the spring of 1994 under the designation F355 was nothing short of a masterpiece. A Ferrari like a Ferrari. On the outside, overwhelmingly alluring. On the inside, innovative down to the last bolt. Gazing at the newborn at the Geneva Motor Show, you could see the features of the iconic 308 and 288 GTO shimmering through, like when happy parents discover certain physiognomic features of a particularly attractive grandmother in the face of their infant. It was curvier and more seductive than its predecessor and once again had the four characteristic rear lights, so you knew with one hundred percent certainty who had thundered past you at 295 km/h, even at night. To summarize the design: Pininfarina made a backwards somersault towards classic elegance that deserves top marks.

As far as the mechanical aspects were concerned, this Ferrari showed the competition how a technology transfer from F1 can be exploited to the maximum. Its kinetic energy was stimulated by a 3.5-liter naturally aspirated V8 with titanium connecting rods, a flat crankshaft and lightweight forged alloy pistons. The biggest advantage, however, were the five valves per cylinder, which were proudly immortalized in the model designation: 355 = 3.5 liters, 5 valves. That made for a total of 375 hp. The last hand-built Ferrari (mass production began with the successor 360) generated more horsepower per liter than the V12 in the McLaren F1! The fighting weight was also right: at 1,350 kilograms, it was two Great Danes lighter than the 348 (1,440 kilos). Price tag: about $120,000.

Three years after its launch, the Italians felt they had to give their superstar the proverbial icing on the cake. As an option to the beguilingly beautiful six-speed manual gearbox, it was the first road car to be available with the semi-automatic gearbox that was originally used in F1. They could have saved themselves the trouble. The shift paddles may have looked futuristic, but the gear changes were rustic and took too long. A production-ready car this was not. In city traffic, the Ferrari jolted from one intersection to the next like an old Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach on its way from El Paso to Tucson. You don’t want to know what Lauda would have thought of that.

It was by no means a foregone conclusion that I would be allowed to drive this ravishing Ferrari on the occasion of its thirtieth birthday. When the F355 first saw the light of day, I was in the middle of my Sturm und Drang period – which meant that my various speeding violations had finally landed me in traffic school and that I had to submit to my first traffic psychology examination. (The whole ordeal would repeat itself just a few years later.) The psychologist, who was wearing a brightly colored short-sleeved shirt and had hair like Guildo Horn (use Google if you must), said I was in real danger of being banned from driving for life. Given my record, any judge could easily rule in favor of permanently revoking my license once the maximum suspension period had expired. I started to feel queasy. I slowly began sliding off of the couch and seriously contemplated suicide. “Relax,” Guildo Horn said as he hurriedly handed me a glass of water, “you’re with me for now. And I’m not working against you, I’m working with you.” I was incredibly lucky to have Guildo Horn as my psychologist, and after paying a shockingly high fine, I got my driver’s license back a few months later. The psychologist had written an extremely sympathetic letter oozing with (invented) admissions of remorse on my part.

My inner voice is telling me that I should be taking this opportunity here to publicly thank this man, who has since retired and who I now count among my friends. My inner voice is female, dark and smoky timbre, probably puffs filterless Gitanes, and I think she wears shoes with high heels. I always do everything she asks of me, I’ve been in bondage to her since puberty. Here goes: Dear Guildo (I’ve only ever called him that, his real name doesn’t really matter anyway), old chap, if you’re reading this, you’ll be pleased, and I know you are, because you’re totally into ramp, even though you keep saying the price is the ultimate in gall, but it’s not your fault, because you’re descended from stingy East Westphalian philistines, so I’ll ask you anyway: Please keep quiet, you’ve been getting a free copy for years (I told Köckritz about the price and that it came from you, by the way, but Michael just shrugged his shoulders indifferently, he doesn’t give a damn), please don’t bother me with it anymore, but I actually wanted to thank you: Guildo, I know I’m deeply in your debt, without you I would probably have lost my license for good and would long ago have ended up in the gutter, with intermittent stays in the drunk tank, without you I wouldn’t have been able to drive the F355 on its anniversary and tip my Panama hat to it with all due devotion, believe me, I’m realizing this very clearly right now, I’m going into myself and am lost in thought like Petrarch on his descent from Mont Ventoux. Hugs, your only Kurt.

The red car with the black interior that became mine for the next twenty-four hours left the factory in 1997 with the full name of F355 Gran Turismo Berlinetta. A small aside here: “Why do you always say that Berlin is nicer when you’re on the phone these days? Nicer than what?” my current significant other, who has become a little hard of hearing from too much acid techno, asked me recently. (I should clarify that the German for “nice” is “nett”.) “I’m not saying Berlin is netter, you deaf little nut, I’m saying Berlinetta.” In the distant past, I really wanted an Opel Manta CC Berlinetta, and I made many long-distance calls across the old Federal Republic of Germany to try to get one: “Hello, I’m calling about the Manta Berlinetta you’ve advertised. Is it still available?” – “Nope, already sold.” I was always at least one phone call too late and was never able to claim the most exclusive of all Mantas as my own.

The F355 was also available as a Targa and a Spider. But the Targa was the no-fish-and-no-meat version for all people who don’t really know what they want. And the Spider was, for example, designed for the wannabe show-offs on Munich’s Maximilianstraße or the stars and starlets rolling along Hollywood Boulevard. The true sports driver opted for the closed version, because he didn’t want any blackbirds shitting on his skull during a neat four-wheel drift.

As soon as I got in and took a look at the circular instruments, I knew what I had signed up for: rev counter up to 10,000 rpm (red zone at 8,500). I could already hear the trumpets of Jericho in my head. I set out to adjust the steering wheel for ergonomic perfection. By today’s standards, it is tilted a little too far forward. My search for a lever was unsuccessful, however. In retrospect, I would have been interested to know whether other car brands – let’s say something halfway sensible like Porsche, BMW, Mercedes or Audi – also offered only such stubbornly set-in-their-ways steering wheels thirty years ago. My immense laziness did not allow me to research this question.

But let’s let the steering wheel be a steering wheel and turn our attention to the truly surprising spaciousness of the cockpit. Surprising, because you don’t get into this Ferrari, you squeeze into it like the Viet Cong into the tunnels of Cu Chi. You feel cramped and closed in when you crouch down into the car like a worm through the open door, but once inside there is so much space that even a driver with a hat on has enough clearance at the top. That’s a good thing, because why should hats-on drivers like me be denied the orgiastic pleasure of driving a Ferrari? We hat drivers have rights just like everyone else, though we are much maligned. The general populace, in all its wickedness, doesn’t mean us well. Just because the occasional hatted person behind the wheel is so slow they end up leading a line of frustrated drivers along the highway waiting for a chance to pass you don’t have to say that it’s always that way.

I fastened my seatbelt and turned the ignition key. The F355 doesn’t roar like its ancestor, the 458 Italia. It hums unobtrusively after starting up. You could even call it unspectacular. But it could also be interpreted as a message. This Ferrari – or rather: this engine – tells you from the outset that it is not a servile American V8 that climbs to the highest mountains of torque merely by stroking it. Forget it. It doesn’t do the work, you do. It’s southern European, after all. If you want to properly feel its power – the message continues – you need to rev it up until your hair bleeds, which means that you only have your left hand to steer, because your right hand is constantly glued to the stick to make sure you’re always in the right gear. Your feet won’t be allowed a break either, the left hand clutches firmly on the wheel, the right hand is in a constant up and down between full speed ahead and reduced speed, you’re heel is nimbly on the brakes in the double-clutch position (exception granted for left-foot brake maneuvers). It’s not going to be a Sunday in the park.

Understood. Best to get everything right right from the start. I revved it up to 6,000 at idle. A brilliant squeal. Cast off. One leap forward and from zero to a hundred in four-point-seven. Unless you’ve just stepped out of the abnormal power rocket that is the Rimac Nevera (zero to 100 km/h in 1.9 seconds), that still seems pretty fast today. Thirty years ago, it must have felt unworldly. I stayed in attack mode and did as described in the previous paragraph, always keeping one eye on the rev counter, because nothing happens below 4,000. A warning light flashed in the back of my head: Caution, mid-engine rear-wheel drive! No ESP! The mid-mounted engine is undoubtedly the last word in wisdom for a sports car. Placing the heavy components (engine, transmission) as close to the center of the vehicle as possible results in an agility and light-footedness that cannot be achieved in any other way. Because everything is concentrated so close to the pivot point, however, the car suddenly goes into an uncontrollable spin. The limit comes unannounced. Suddenly, it’s just there. But you’re not.

Two years ago, I drove the McLaren 750S at Estoril. In a fit of megalomania, I activated the variable drift control with the most extreme angle. What had to happen happened: At the exit of a left-hand bend, I was half a second too early on the gas. Spurred on by its primal instinct, the beast suddenly swerved wildly to the right. It was only thanks to the ESP being switched on that I was able to prevent the car from taking off. How would the Ferrari behave? I don’t know. At the crucial moments, I lifted my foot off the gas every time, but not out of cowardice. Out of common sense. This F355 hadn’t seen a single scratch in twenty-seven years of existence. I had no intention of changing that. As we all know, the devil never sleeps. At worst, I would have had to stand in front of the owner and say: “You can have your Ferrari back, it’s stuck to a tree ten kilometers from here. Actually, it’s not stuck to the tree, it’s more wrapped around it. I mean: was wrapped around it, because when the fire department tried to remove it from the tree, it broke in half. I’m so sorry. Can I buy you a small beer in return?”

The F355 felt neutral right up to that line where things could (perhaps) have become dicey. It let itself be pitched around the corners with almost Lotus-like agility. Abrupt load changes were welcome. In other words, in a quick succession of bends it remained true to its line, meaning that it didn’t sway in such a way that you would have lacked the momentum for the next bend. The brakes instilled me with confidence right from the first negative acceleration maneuver (I like the word because of its rarity, it occasionally flies at me like a white raven, in the future I want to use it more often). The pressure point on the pedal is not too hard and not too soft, it is perfectly at the golden mean. The Ferrari also behaved very well in a straight line, with no nervous to and fro on the front axle at high speeds or similar antics. The steering is more sensitive than the ABS, where you can feel that this is a car from the nineties.

In short, I felt very comfortable in and grew fond of this Ferrari in no time at all. I stopped keeping it constantly on the move. Wouldn’t that have degraded it to a mere barrel organ? No. We glided leisurely through the countryside in unison and marveled at each other, the F355 and I, and I can assure you, friends, I could tell by the looks on their faces that a driver with a hat like that in a Ferrari completely confuses people, it throws those nitwits out of their clichéd thought patterns, almost squares the circle. Hey, if the hat fits . . ..

This story began with Luca Cordero di Montezemolo. It should also end with him. As the F355 was the first road-going model built under his aegis, I often had to think of him while driving this car – and of this story from twenty years ago. It shows what a fun guy this successful man and workaholic could be (and still is): I had traveled to Milan to interview Diego Della Valle, CEO of luxury fashion manufacturer Tod’s, at his company headquarters. His secretary greeted me at the reception and escorted me into the conference room. Signor Della Valle was on an urgent phone call and it would take a few more minutes. Five minutes later, the door opened. But it wasn’t Diego Della Valle who entered the room, but one of his best friends: Luca Cordero di Montezemolo. Hey, would you look at that, I thought. He shook my hand and introduced himself. Not as Luca Cordero di Montezemolo, but as Michael Schumacher: “Michael Schumacher,” he said, pronouncing the name the English way, “nice to meet you.” (Montezemolo and Schumacher were about to win their fourth F1 title in a row.)

I went along with the joke: “This is such an honor, such a pleasure to meet you.” Montezemolo, as Michael Schumacher, told me that Diego Della Valle was still on the phone. Could he keep me company in the meantime? Supposedly a certain Luca Cordero di Montezemolo was also in the house, had I ever heard of him? No, I said, who would that be? Not important, he replied. It went on like that for ten minutes. Among other things, I asked “Schumacher” how he rated his own driving skills. Answer: “I’m the best, all the others are just nosepickers.” Then came Diego Della Valle. “Michael Schumacher” said: “Ah, there’s that Montezemolo.” It was just wonderful, and if I had been driving today’s birthday car back then, I would have said to the Nobile dei Marchesi: “Michael, I love the F355!”

Text by Kurt Molzer

Photos by Matthias Mederer · ramp.pictures

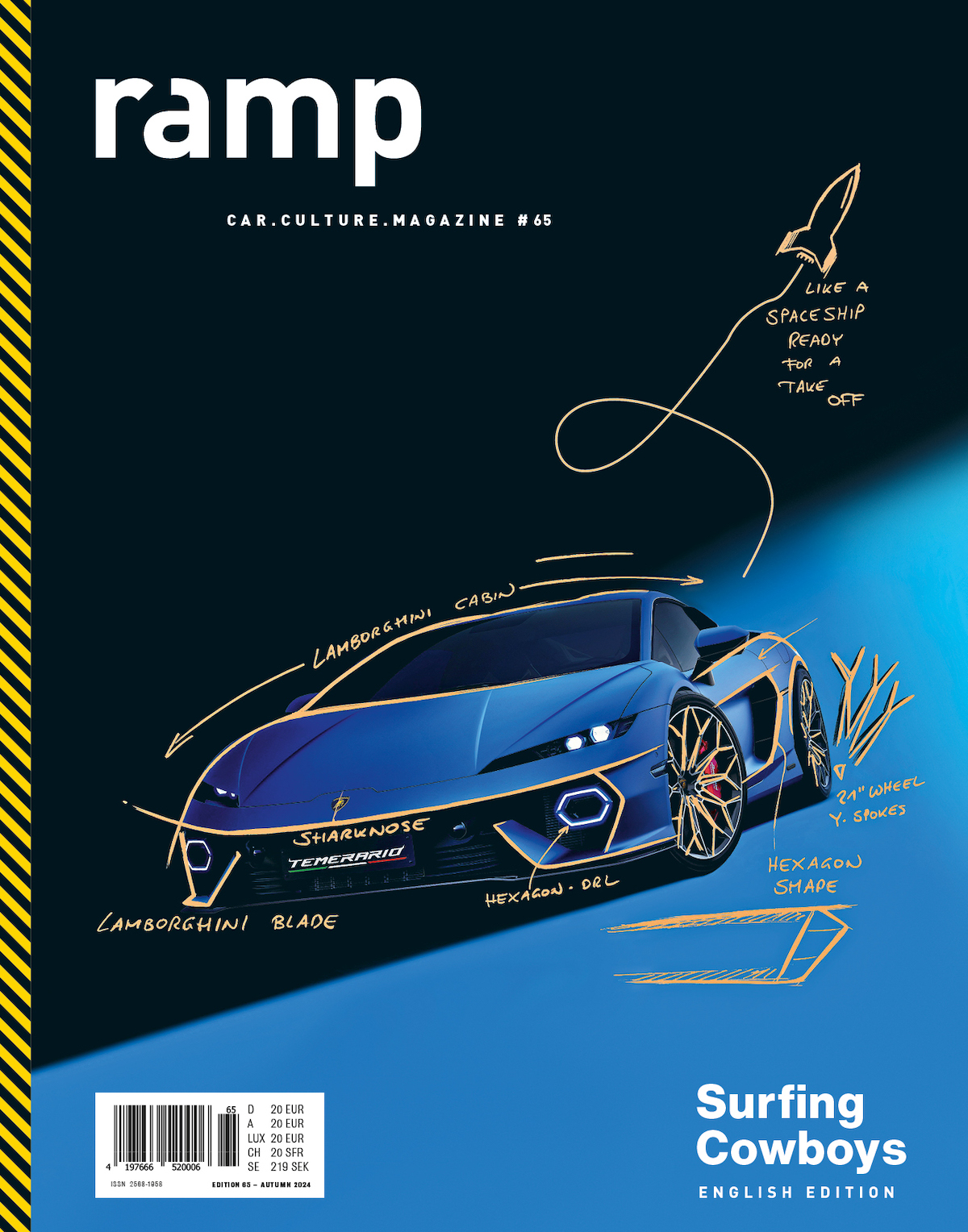

ramp #65 – Surfing Cowboys

If you think “Surfing Cowboys” refers to neoprene-clad prairie riders or surfers wearing cowboy hats, you’re slightly off the mark in this case. In the latest issue of our Car.Culture.Magazine, it’s about the meeting of two quintessentially American archetypes, both embodying a deep longing for lived independence and untamed, self-determined freedom. Find out more