It was the autumn of 1961, and a hot-headed student at the University of California was beating the Porsche 55 356 A Speedster of a professor friend of his through the streets of Los Angeles. Thinking about the failed exam, he drifted into a bend so fast that the Zuffenhausen sports car crashed into the side of the façade of a celebrity villa in Long Beach. At the time, no seat belts or airbags protected the 22 year old Porsche driver from serious injuries. But before the rigid steering column could become a fatal spike, the youngster skidded over the flat windscreen of the Speedster onto the freshly mown lawn of the front garden and came to rest unhurt. He escaped with a scare.

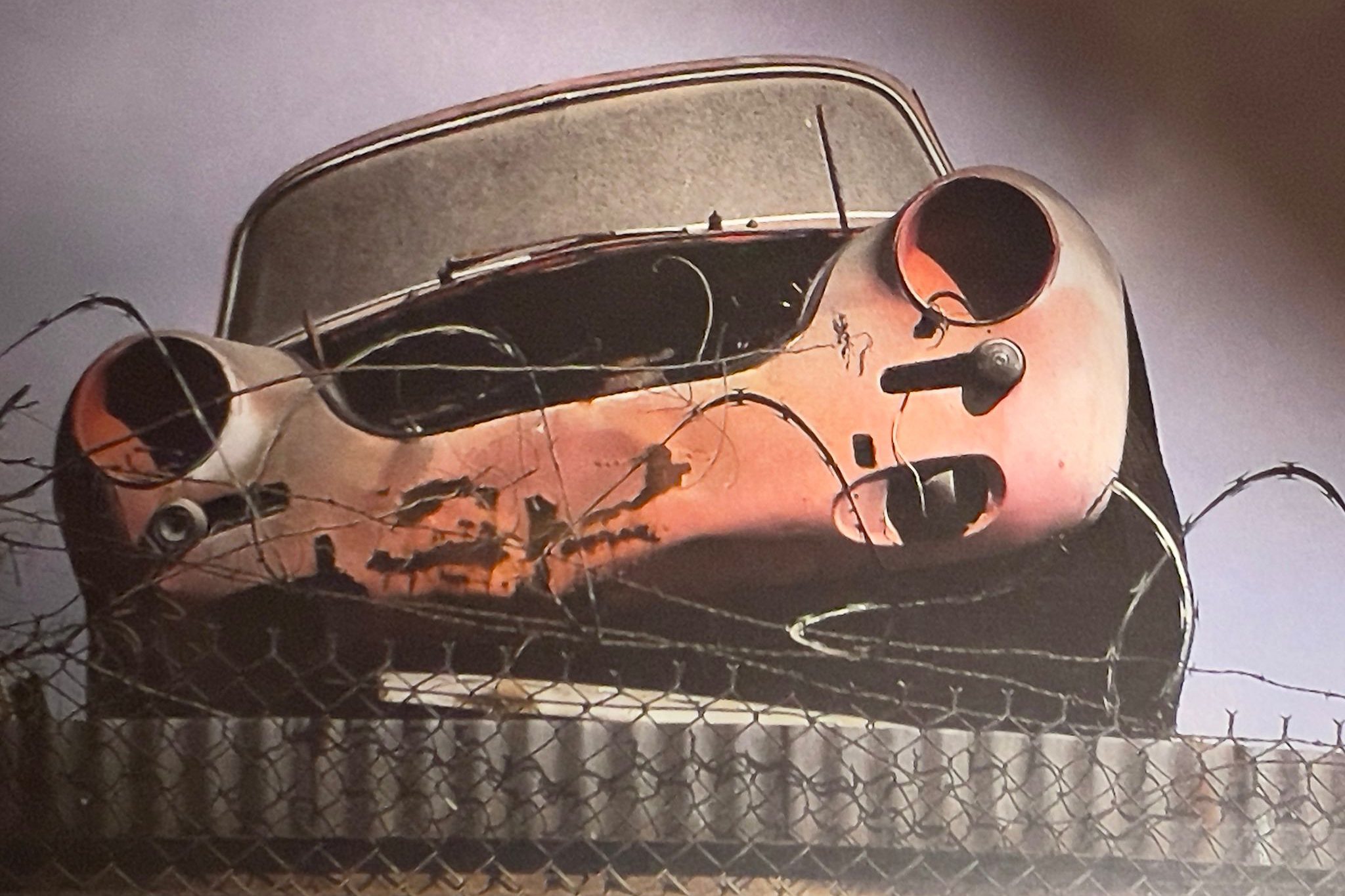

The expensive two seater, on the other hand – although well insured – was so crumpled that it was only worth scrap metal. Out of attachment, he nevertheless parked his dream car in his garage for a few years. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the fun car finally ended up in a scrapyard in Los Angeles, where a German-born scrap dealer let it mature under a canopy for a few years.

There, the Speedster was in good company among other exotic cars. Rudi Klein, then aged 38, a native of Rüsselsheim who had emigrated to the USA via Canada at the age of 21, had started to collect Porsche and Mercedes vehicles – of any type and in any condition – on an area the size of a football pitch. And in doing so, he showed foresight. He did not allow himself to be irritated during the 1974 oil crisis, which at times rendered disproportionately fuel-efficient sports cars almost completely worthless. Klein bought against the trend, dirt cheap, the oil crisis calmed down and the businessman was able to sell at a healthy profit. In the years that followed, he shipped 20 of the legendary Mercedes 300 SLs alone back to Germany, either as roadsters or with gullwing doors.

Back then, in the seventies and eighties, Klein still ran the classic car business in a tough and purely commercial manner. Today, the trained butcher and his team of eight almost only gut newer accident-damaged cars and sell them in parts. The classic cars, on the other hand, remain untouched, with a few exceptions. Over the last ten years, Klein has turned into a quirky collector and has become increasingly difficult to access. No journalist has entered his grounds, which now cover two football pitches, for over a decade, and other visitors are also being admitted less and less frequently.

Author Tobias Aichele researched a rare Glöckler-Porsche for his new book “Mythos Porsche”. This vehicle is considered the forerunner of the Zuffenhausen racing car 550 Spyder- During a phone call with a Porsche insider in America, he heard about the mysterious scrapyard in California. During further enquiries, Aichele came across Klaus Heffels, head of the classic car enthusiasts “Scuderia Lufthansa Classico” in Frankfurt, one of the few people who enjoy Klein’s trust. He was immediately willing to arrange the contact. But that was not the end of the story for Rudi Klein. It was only a meeting at the classic car meeting in Hattersheim near Frankfurt in June 1996 that created the necessary sympathy and thus the provisional agreement to enter the area with a photographer. Three months later, photographer Joachim Schahl from Stuttgart and Tobias Aichele were sitting in a hire car, driving from Los Angeles City along the “Santa Ana Freeway” No. 5, north-east, which joins the “Long Beach Freeway”, No. 710, in the east of the metropolis of millions. They followed this to the north and reached the Firestone Boulevard exit after around 60 minutes.

Klein urged the team of journalists to exercise caution before their departure. Southgate is one of the most dangerous neighbourhoods in the city, comparable to the Bronx in New York. Black gangs would dominate the scene. Shootings are the order of the day. We were told to lock our car doors in this area and not to fill up with petrol or make any other purchases. The tension was rising.

From the outside, there is nothing to suggest that there is much to see here at 8935 Alameda Street: a neat, 20 metre long blue and white wall with battlements bears the inscription “Por Foreign Auto Wrecking”. Beneath it looms a heavy iron gate that only opens when friends or good business partners are expected. Behind it is another world. The heavy iron gate falls back into the lock, and Klein’s Mexican employee Art de la Rose leads the guests through a corridor that is barely visible due to the piling up of spare parts. Man’s width, into a dingy office. Amidst numerous piles of paper, Rudi Klein sits in front of a hopelessly cluttered metal desk, its rusty hammer finish reminiscent of old containers. He is studying the “Financial Times”, or more precisely the current dollar exchange rates, which can have a major impact on his international business. The only window in the room provides hardly any light, as it is made of frosted glass and has strong bars to protect against intruders. It is also covered with two German-language posters: a racing poster from the 1963 Le Mans endurance classic, featuring Porsche’s plastic 904 GTS flounder, and the poster announcing last year’s classic car meeting in Hattersheim. Nimble as a Wiesel rises to greet the strangers from his home country in Hessian dialect. His uncomfortable-looking office chair with metal armrests swings so much that seconds later it is still bobbing like a wooden sign dangling in the wind in the Wild West.

Standing a good 1.85 metres tall in the room, Klein’s full beard gleams silvery, the dark blue jumper irritates cold-suffering Europeans, who generally sweat in the shade at over 20 degrees Celsius. His trousers are conspicuously clean and creased, but battery acid has eaten holes in them and brake fluid has caused yellowish discolouration. We only learn that this outfit characterises his work philosophy later, when we see the parts dispatch. Second hand parts may well show signs of use, but they are sold neatly cleaned. Klein’s office is a hive of activity. All day long, purchase requests ring out over the radio. The system to which all North American scrap and parts dealers are connected is called “Circuit”.

Klein’s ears are trained to listen to the fuzzy enquiries.

He repeatedly rushes to the radio in the middle of a conversation with his guests and frantically but energetically makes an offer – like a financial broker on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. “Business is business” is his unmistakable message for his flourishing parts trade. Four computers support the business. Rudi Klein’s older son Benjamin, whom he affectionately calls “Benji”, is heavily involved in the day-to-day business. The 21 year old, lanky and at least a head taller than his father, knows what is in stock. The head of the family gives him a free hand even with the tricky pricing. “A feel for prices is the most important thing – and my son has it,” says Klein, underlining his confidence in his son. So he also signs off with him when the impressive round trip begins.

While the author and photographer follow him in single file, Klein lectures with the conviction of a teacher and the dramaturgy of a writer. It is purely coincidental that the inscription of the former school “St Andrews”, which was used for teaching between 1893 and 1932, is right above the first building we reach. Beneath the weathered roof and in front of the facades of the former school building, which have already undergone countless makeshift repairs, thousands of tonnes of worn and dented car bodies are piled on top of each other. Apart from the inscription, nothing resembles an austere educational building; the scenario is more like an adventure playground that could not be more beautifully invented. Like an ant scout, Rudi Klein finds the best way through the piled-up towers of car bodies. He doesn’t care that his guests pick up dirty clothes on the tour. Nevertheless, he warns them to be careful of the sharp edges of bent mouldings or rusty bumpers. After all, we are in America, where whole hordes of lawyers earn good money from liability claims.

Klein points to an overgrown spot. This is where the Porsche 356 Speedster that crashed with the aforementioned student in the early 1960s used to rest. “A German museum owner talked me into it a few years ago,” he explains with a mischievous smile. He knew how to convince Klein by promising to leave the car as it was: crashed and dirty. Today, the sports car is under glass in the Auto + Technik Museum Sinsheim. Museum director Hermann Layher sees it as a work of art, comparable to an object by Beuys.

After all, no accident cars have been preserved, but there are plenty of restored Speedsters. “Incidentally, I only returned another classic car to Germany a few months ago,” adds Klein. It was the only Glöckler Porsche built with the unconventional coupé bodywork. The aluminium car, which was originally powered by the 130 hp 356 Carrera engine with a king- shaft steering system, is currently being restored by Klaus Heffels, an accomplished classic car enthusiast from Frankfurt. Klein bought this car over 20 years ago through an agent, who paid him a commission of 500 dollars for it. At the time, he was told that there was a rare Porsche on Hollywood Boulevard. Armed with a 1935 Chevrolet tow truck and enough cash, Klein drove to Hollywood in 1976, pulled the real car out from under ten completely soiled blankets and bought it for 3,900 dollars. The 500 dollar agency fee was well worth it. The coupé is to be used again in a classic car race this year.

The fact that Klein has sold two Porsches in recent years, the Speedster and the Glöckler, is not of the slightest significance in quantitative terms. Southgate has an estimated 3,000 other pieces from Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen in good to poor condition. And there are also rarities such as an Abarth Carrera and a 904 GTS. The Abarth Carrera is a streamlined aluminium coupé built on the 356 B chassis by tuning master Carlo Abarth on behalf of Ferry Porsche. The reason for the project in 1960 was a loophole in the FIA regulations, which allowed a minimum weight of 775 kilograms in the medium GT class, which could only be achieved with a special body. Only 23 of the racing cars with up to 180 hp were built.

At 116 units, there were only slightly more vehicles of the 904 Carrera GTS. Also in the early 1960s, Ferry Porsche’s eldest son Ferdinand Alexander, then head of the model department, designed the racy plastic body of the mid-engined sports car, which weighed just 650 kilograms and, like the Abarth Carrera, was initially equipped with the 180 hp, four-cylinder, king-shaft engine. Eight examples then received the new six-cylinder boxer engine, which was designed for the newly launched 911 at the time.

While the two particularly rare Porsches slumber in a hall, most of their ordinary counterparts are exposed to the great outdoors. “I only come here once a year,” Klein points to a completely overgrown corner where several Porsche 356s have been sleeping rough for endless years.

Some of the round bodies have already been buried by bushes and grasses. The specimens are so close together here that it is only possible to get away by climbing. Rudi Klein gives clear instructions that only damaged parts may be entered. He loves his wreck landscape as it is: “Everything should stay like this.”

The imposing front of a Lamborghini P 400 Miura SV sports car, which hangs diagonally in the air on engine blocks, has also been untouched for years. On the matt blue paintwork, the lovely red-flowering geraniums, which grow from underneath through the left-hand ventilation grille, are a real eye-catcher. The retracted sleeping eyes of the sports car create an almost surreal still life motif.

Klein has no eye for this picture at the moment. Without comment, he reaches down to the floor and retrieves a slightly rusty centre lock from a racing car. It disappears into his trouser pocket along with the dirt. His inner joy at the find is written all over his face. The expedition arrives at a shelter from which an acrid odour is emanating. Klein pushes aside a rusty strip of corrugated iron and one by one the “explorers” peel themselves inside. Covered in pigeon dung, ten more classics face a bleak future. Nothing can be saved here, the faeces trigger chemical reactions, everything is eaten away.

The next hall brings more joy, romance and memories. A dusty ceiling cannot hide the beautiful sight. Paint gleams, chrome flashes and leather smells. A Mercedes-Benz 500 K, a one-off with coupé bodywork, built in 1935 especially for racing legend Rudolf Carraciola, appears as if in a different setting: Klein stops almost reverently and murmurs: “I would never sell a car like this. It was built just the way I like it: with a long snout, a small cab and a short rear end.” The special coupé has been parked here for ten years and will probably remain there for the next ten.

Maybe another tyre has lost air, the layer of dust on the ceiling is probably even thicker, but otherwise …

After four hours, Klein and his guests have reached the other end of his magical world. Once again, they come across a high wall with rolled barbed wire looming on its upper edge. But the man from Rüsselsheim has another surprise in store: a second hall on the opposite side of the road. However, the temporary tour guide does not ask the guests to walk round the block. Instead, the expedition participants climb into the brand new Audi V8 parked directly in front of the iron gate of the entrance (Klein: “I love Audi and its ancestors!”) to cover the few metres. Once again, the streets are deserted, with only a dark-skinned man loitering on the street corner. With almost shaky hands, Klein searches for the right key for the heavy padlock on the gate. 22 very similar keys from the Master company dangle from his key ring. “Is the black man looking,” he asks anxiously? “No,” photographer Schahl reassures him. He has finally got the right one, after 13 attempts – there are no German-style alarm systems here. Klein repeatedly blocks the passageway with his right hand until he has removed some cords from rusty sockets that would supposedly trigger an alarm. But: assuming the signals would sound, who cares here?

Who should hear that?

The hall is cool, even damp in places. Some of the walls are covered in mould in all colours. Beams of light fall through the skylights of the former factory building onto cars that enthusiasts would give anything for. An aluminium convertible built in 1955 by the Darmstadt-based company Autenrieth on the basis of the BMW 503. The bodywork specialist dispensed almost entirely with the typical BMW front-end design for the 60 vehicles it built up to 1962, preferring a US-style shark’s mouth. Major US importer Max Hoffmann w a s interested in the vehicles during these years, but BMW prohibited exports to the USA. So this car, which at the time already cost almost 100 per cent more than the basic saloons, which cost around 13,000 marks, crossed the pond in a roundabout way.

The Iso Grifo convertible remained a one-off, which was shown in its final version for the first time at the 1965 Frankfurt Motor Show. Fuelled by the Chevrolet Corvette V8 engine, the sports car with its predatory, crouching appearance was the result of a collaboration between bodywork specialist Nuccio Bertone and chassis professional Giotto Bizzarrini. Klein is attached to this exotic company because his first “noteworthy” car was a 1968 Iso Grifo coupe in dark blue with the Californian licence plate “153 BEV”. This car is also still in Klein’s collection.

Mercedes is represented here with an entire armada. Seven 300 SL Roadsters are crammed closely together next to four 230 to 280 SLs with the famous pagoda roof. Klein draws particular attention to an aluminium 300 SL Gullwing. This lightweight version, of which only 29 were built, was used successfully by the North American racing team “NART” in the 1950s. Another Mercedes is not initially recognisable as a product from Untertürkheim. In 1938, it was given a customised body shell by the renowned car manufacturer Bauer from Stuttgart. Instead of the typically dominant Mercedes radiator grille, it had two rather dainty cooling air openings.

As the group leaves the second hall, about which there is still much to tell, the warm evening sun bathes the scrap metal landscape in orange-yellow light. In front of the hall, a four-door Packard beckons once again, bearing the proudly stretching swan as a radiator grille. A few years ago, Klein wanted to take part in the “2,000 kilometres through Germany” classic car regularity event with this luxury vehicle from the 1940s. “Then they stole the rare balloon tyres from me,” he concludes the chapter on veterans’ meetings. Since then, the black Packard, in which even the passenger window is now only covered with a cloth, has met the same uncertain fate as thousands of its peers. Nevertheless, Klein still has a classic car dream, namely to drive the only Auto Union 16-cylinder racing car built in the 1930s. But taming this monster, with its 520 hp six-litre supercharged engine, will probably remain a dream even for the spoilt German-American.