William Heynes and Amy Shore met just over two years ago. Will is the grandson of the original Jaguar chief engineer, Amy a much-published car photographer. A year and a half ago, they set up their workshop for classic Jaguar E-Types. And this year, the two are getting married. We visited them at their place of work.

Matching numbers. Everything perfect and in its place.

This should be understood literally – because there are two ways to restore an automotive classic: With suitable parts so the vehicle runs. Or with the correct parts that were once manufactured for exactly this car or its series. The latter is a true mark of quality for experts and enthusiasts. For some people, it is also a way of life. William Heynes is one of them. The grandson of Jaguar’s chief engineer from 1946 to 1970, who was responsible for all Jaguar models of the time, is currently wrestling with some parts in the engine compartment of a red E-Type: “This has got to be the worst screw ever!” the twenty-nine-year-old grumbles.

The William Heynes Ltd workshop is located in western Warwickshire, in a small industrial building near the town of Alcester. Rock music is blaring from a small loudspeaker in the corner, mechanics Dave and Josh are working on two E-Types, the buzz of fluorescent lights can be heard from the high ceiling. Above that, on the second floor, the busy clicking of a computer mouse. Photographer Amy Shore is working on a series of pictures she took at Goodwood – a place that has had an enormous impact on her life: “Visiting my very first Goodwood Revival opened up the classic car world for me. That started the spark for me of owning a classic car and having a life with classic vehicles. It started off what would then become my career.” And indeed, it was the start of a stellar professional journey, with assignments from magazines, car collectors and advertising agencies to follow.

Something else entered Amy Shore’s life at about the same time: her 1985 Austin Mini Mayfair, nicknamed “Mayo” due to its off-white color, as the name suggests. She has owned the classic for a good thirteen years now. In 2015 she went on a thousand-mile road trip across the Scottish Highlands. She loves speed, which is why she also has a racing license. “One thing I’ve always loved about classic cars is that every day truly is an adventure,” she says, “And what is this life if you’re not feeling alive?”

Amy Shore and William Heynes met about two and a half years ago. Not at a classic car event, however, as one might expect, but at a dinner with mutual friends. At the time, the thirty-one-year-old was looking for a place to live closer to her friends and family in Leicestershire. Will asked her if she would like to move in with him, his house being in the area where Amy was looking. “We’ll find out really quickly if it will work or if it won’t,” he said. It worked. The two went from being roommates to becoming partners and are planning to get married later this year.

“Starting this workshop was difficult, but it was the single best decision I have made,” says Will. “Though it was easily the scariest thing I have ever done in my entire life,” Amy adds. Raised eyebrows, a quick glance at each other, then both burst into laughter. But why set up a workshop just eight months after getting together? At the time, Will was working on the family farm and restoring E-Types with his father. “Chassis 26,” he recalls. “A high-stress car.” Amy explains: “Will goes through time with chassis numbers.” William remains serious and says: “I came home one day and said, ‘We need to do this.’ Either I go and get a proper job or we do this workshop thing.”

They did it. The pair spent four weeks driving all over the country to find everything they needed. All second-hand. “The only thing we bought brand-new was the ramp,” says Amy. The first orders came from friends in the classic car scene, where they quickly made a name for themselves. Will is responsible for the workshop itself, while Amy, in addition to her work as a photographer, handles the advertising – with her own photographs, of course. Downstairs in the shop, a starter motor whines, a sonorous, slightly bubbling, but throaty engine sound can be heard.

Mechanic Josh has started an E-Type and is rolling it backwards. Will has gone back downstairs, looks at the vehicle and says, “When you find the right car, you find out the history of the car. And then you set about a complete forensic rebuild, where everything is exactly as it should be. It’s all about the thought processes, the organic feeling of it.” In keeping with this philosophy, Will works exactly according to his grandfather’s specifications. Everything that happens in the workshop conforms to the original guidelines that applied at the Jaguar factory. Three conditions must be met at the start of any restoration, as Will explains: “A good car as the foundation. Matching numbers. And it must be complete. Right down to the seals. Their shape is different today.” As you can see, here is a man who is concerned with preserving the spirit of the vehicles rather than glossing over the patina.

His work ethic gave him projects like the Sherwood Green “AFD 250” that Josh has just moved. Also known as the “860002”, it is the second right-hand drive E-Type ever built. It’s not being restored here, however, but merely being serviced. Will explains what makes the car so special: “Chassis number two is a so-called fixed head coupe from the first development series. And it’s the only E-Type to leave the factory with a 3.4-liter engine from the D-Type. The Holy Grail of E-Types and an absolute one-off.” Will glances out the window, looking pleased. In this small, analog world, he can really get in the flow of things.

Of course, the two want to earn a living with the workshop. “But it’s not what I’m here to do,” Will says. “The bigger picture is to leave the industry in a better place when we’re no longer here.” That’s why, after less than two years in operation, they’ve taken on their first apprentice. Next up, they’ll restore a C-Type and look after a Jaguar Mk I in historic motorsport. After that, they will hopefully continue to measure time in chassis numbers for a long time to come. Incidentally, the chassis number when they met was number 36.

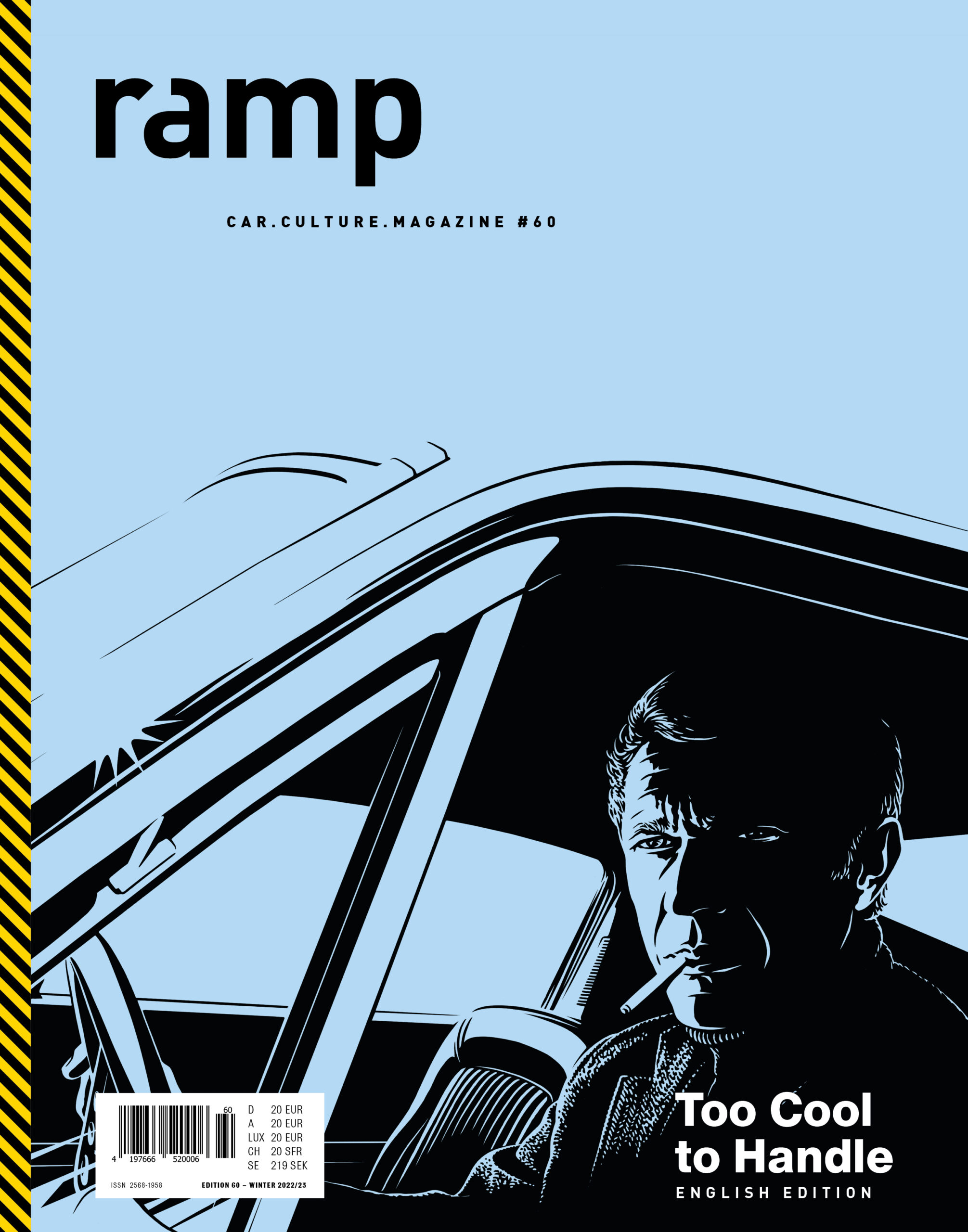

ramp#60 – Too Cool to Handle

As a high-impact multimedia brand that takes an all-encompassing, end-to-end approach to publishing, ramp is an absolutely authentic expression of quality, integrity and excellence. Its trailblazing luxury magazines, recognized with numerous awards over the past 15 years, have been celebrated for their cool and unconventional, not to mention inspiring and pioneering style, since day one.

ramp, the lavish and beautifully designed coffee table magazine, celebrates the enthusiasm for cars and driving in a passionately subjective, personalized fashion.

Immediate, authentic, intense. Fresh perspectives, avant-garde

A magazine about coolness? Among other things. But one thing at a time. First of all, it’s off to the movies. There’s this businessman from Boston who helps relieve a bank of a substantial amount of money. The insurance companies are on to him, but they can’t prove a thing. That, in a nutshell, is the plot of the film classic in which Steve McQueen plays Thomas Crown, who remains a mystery to the viewer throughout the entire film and who the actor plays with incredible composure, exuding absolute coolness at every moment. The German title of the film – Thomas Crown ist nicht zu fassen – hides a wonderful play on words, by the way. It could mean: Thomas Crown is unbelievable. Or it could mean: Thomas Crown cannot be caught. Cannot be seized. Cannot be grasped hold of. He’s just too cool to handle. Much in the same way, coolness also eludes our attempts to grasp it. A fundamental vagueness shrouds this fascinating phenomenon of longing and desire.

We’re fascinated by the irrational, the incomprehensible, the unbelievable. That’s why we also enjoy breaking the rules. We are living contradictions, as neuroscientists and psychologists so dryly explain. Our irrationality, innovation research tells us, is the secret to our creativity. It is our irrationality which insists that it is not we who must adapt to the world, but that it is the world that must adapt to us. This is another reason why any kind of progress depends to a large extent on our irrationality.

“If people never did silly things, nothing intelligent would ever get done,” the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once so aptly said. The physicist Richard Feynman opens our eyes to another aspect in this regard: “Physics is like sex,” he explains. “Sure, it may give some practical results, but that’s not why we do it.” And that’s just about how it was with this issue of ramp. Sort of.

With this in mind, enjoy!

Text & Photos: Marko Knab · ramp.pictures