Imagine you get a call. You’re given the chance to drive ten laps at the Challenge & GT Days at the Red Bull Ring in Austria in each of the following four race cars: Ferrari 458 Italia GT2, Porsche 991 RSR, Porsche 996 RSR, Ferrari 333 SP. The task, by the way, is to show what you’ve got.

Oh shit!

Some stories are so unbelievable you think they can’t be real. This is one such story. It begins three months ago at Ristorante Pfauen, Reutlingen near Stuttgart, Kanzleistraße 52. Apulian cuisine. Our editor-in-chief invited the staff and a few friends to dinner. A big get-together. One of the guests at our table was a wiry and extremely likeable man in his late forties. I noticed that he listened attentively whenever I said something. Usually with a slightly mischievous smile. The next morning, my phone rang. It was the editor-in-chief: “I just sent you an e-mail. Take a look at it, that’s all I’m saying.” I couldn’t believe what I read: “You’ll be driving ten laps in each of the following four race cars on June 8 as part of the Challenge & GT Days at the Red Bull Ring: Ferrari 458 Italia GT2, Porsche 991 RSR, Porsche 996 RSR, Ferrari 333 SP. By the way, I’m supposed to tell you that P. sends his regards.” Attached was a photo of each car (both of the Porsches, of course, are 911s – 991 and 996 are the internal type designations).

I immediately called back. “Is this some kind of belated April Fool’s joke?” I asked.

No joke, the editor-in-chief replied. P. used to race professionally – not in some Mickey Mouse races either, but in the World Endurance Championship. At dinner the night before, P. felt that I had had quite the big mouth, but instead of stuffing it with spaghetti carbonara, I kept boasting of my alleged driving prowess and assorted race car experiences. And because P. is the kind of person who believes that when you do something you should do it right, and because he likes a good story, he decided before he went to bed that night that he would rid this big-mouthed Austrian writer of his habit of shooting his mouth off. Let him show us what he’s really made of – in a real race car. And why stop at one car? Let’s make it four! P. owns the Porsche 991 RSR and the Ferrari 333 SP himself. A friend of his, a former English racing driver, is the owner of the 969 RSR and the 458 Italia GT2. Both of them were coming to the GT Days to do a few laps on the track. In a midnight phone call, the Brit assured P. that he would make his two cars available to yours truly and that finally someone would show me what’s what. Early this morning, P. then rang up the editor-in-chief, who was still in bed, to inform him of his idea. (Since P. prefers a certain level of anonymity, we will continue to refer to him as P. throughout this story.)

And then all of a sudden it was June 8. I woke up early in the morning hearing voices – two, to be exact. One was soft, frail, uncertain: “This is your big day, just believe in it . . . Hmm, or not, I don’t care.” The other was thundering, ominous, unmistakable: “This is going to be your Armageddon!” During the night, tormenting self-doubt had prevented me from falling asleep. Again and again the same questions circled through my mind: Am I really up to this? Has there ever been a better opportunity to make a complete fool of myself? Was I going to kick the bucket? Getting up was tough, I didn’t exactly feel rested. At ten o’clock I was at the track. White clouds floated like a flock of sheep over the circuit, which lay there nestled in the mountain landscape.

So the Challenge & GT Days it was. Organized by Heinz Swoboda, an Austrian Ferrari enthusiast with Goodwood experience. The event, which takes place over a period of two days every year, gathers together mainly Ferrari race car owners from all over the world. I rolled through the paddock and stopped at the rear entrance to P.’s pit. The wide, flat, fearsome Ferrari 333 SP, an open-top prototype sports car, roared venomously in warm-up mode, seemingly twice as wide as in the YouTube videos I’d watched about a hundred times. I rubbed my eyes to be sure, but that made it even wider and more terrifying. Next to it was the Porsche, still at rest. P., who was already wearing his racing overalls, was conferring with an engineer from his crew. The Porsche is cared for by a four-man team from Classic & Speed, a company at the Bilster Berg Drive Resort that provides professional on-track service. The Ferrari is looked after by three guys from Michelotto, a race car manufacturing company based in Padua (the 333 was a joint development between Ferrari and the engineers at Michelotto). Both crews, who arrived with large transporters, care for the cars throughout the year. That makes things much easier for P., who only has to concentrate on one thing: stepping on the gas. When he saw me, he immediately had that mischievous smile on his lips again. We greeted each other, he introduced me to his team and told me that I would be getting started in about an hour – first with the Porsche 991 RSR, which he said was the most docile of all the cars here, finishing it off with the toughest of them all, the Ferrari prototype. The English guy had his cars in the pit next door, also with two support teams taking care of their every need. (The Ferrari 458 was in the trusting hands of JMP Racing, a legendary Monaco-based racing team that was founded by former F1 driver Jean-Pierre Jabouille and which has experience in endurance racing.) We went over for a visit, and P. introduced me. The Brit had thinning reddish-blond hair and was in his early fifties. He had heard a lot about me, he said, stroking his chin with one hand. I replied by telling him what an honor and great pleasure it was to drive his cars and “show him what’s what”. “Sure thing, Kurt,” he said, as he took his crash helmet from a folding chair and got ready for the chase. P. went back to his pit and climbed into the 333.

I stayed behind in the Englishman’s garage, and suddenly everything seemed so surreal. There I was, standing in front of this motley Ferrari 458 Italia GT2, built in 2015, third place in the GTE-Pro class at the 24 Hours of Le Mans that same year. The drivers’ names painted in white letters on the side edges of the roof: Giancarlo Fisichella, Gianmaria Bruni, Toni Vilander – two former F1 drivers and endurance masters from Italy, plus a Finnish class winner in the FIA GT Championship. I froze in awe and asked myself: What was I doing driving this car? Grave doubts ran through my mind. I went over to the pit wall. All hell was breaking loose on the track. Probably more than half of the forty-two entrants were out there doing their laps. They may have been gentlemen drivers, but they certainly weren’t acting like gentlemen. A dark rumbling Mercedes-AMG GT3 came hurtling out of the home bend, chased by a pack of hysterical Ferraris. The mob was already on the straight, when behind them, like a horseman of the apocalypse, on his last legs and half up on the curbs, another pursuer appeared: P. in his open-top prototype wearing his white-and-gold helmet! At the end of the finishing straight, towards the entrance to the Niki Lauda curve, the marshals were already frantically waving the blue flags signaling the slower drivers to let the faster ones pass. It took only a few moments until the 333 SP – also known as the Eardrum Splitter among experts because of the devastating acoustics of its twelve-cylinder F1 engine – left the slower cars behind like a pile of used cleaning rags, thundered up the hill, turned the corner to the right and could still be heard when it had long since reached the Schönberghof and made the holy water tremble in the parish church of St. Stephan a little further up the hill. Damn, I thought. I’m supposed to drive this beast of a car? How stupid could I be to have gotten myself into this? I thought about whether it wouldn’t be the smart thing to do to just run away and hide in the woods behind a feeding trough until the whole circus was over. But then one of the guys from Michelotto was there standing next to me, and he asked me: “Are you looking forward to it?” And like a reflex, I answered, “You bet!”

The hour of truth:

Porsche 991 RSR

I went to the car in the paddock to get my racing overalls, crash helmet and the rest of the equipment, got dressed and climbed in the car. I was crouched inside the Porsche 991 RSR as if in an Indian tiger trap. Ultra-tight bucket seat. Headrests jutting far forward at the sides. Roll cage. Safety nets. Impact protection for the legs. Not an inch of freedom in which to move the upper body because of the extremely tight six-point belt. In front of me I was staring into two open pipes – cooling air for the driver during the heat of battle. On the lower right, the fire extinguisher, exposed hoses and cable lines, nothing but naked brute force. Since I’m taller than P. and the seat in the RSR is not adjustable, the pedals had to be moved forward, but that took no more than a flick of the wrist. The steering wheel (or rather: the multifunction controller with which you can also steer) was a science in itself. In the upper section, it has sixteen LEDs, small lights that light up in different colors as the engine speed increases. In the center is a display that shows the gears, among other things. All around are ten buttons and five dials for brake force distribution and whatnot, but I wasn’t interested in those or I would have gone crazy. The car, four years old, had raced at Le Mans back in 2018. Driven by Timo Bernhard, Sven Müller and Romain Dumas, the car had to retire after seven hours with suspension damage. The four-liter, six-cylinder naturally aspirated engine producing 503 hp is located in front of the rear axle for better weight distribution (which also creates more space for the enormous diffuser). In other words, this 911 is not a rear-engined race car, but a mid-engined one. Due to regulations, there is no ABS. The worst thing now, before I pressed the start button, was this uncertainty: What awaits me out there? What will the Porsche do to me? How will I cope with the traffic out there? During his instructions to me earlier, P. had said, “Stay on the line. Don’t deviate from it just because you think: I want to be nice and let the faster drivers pass. That only leads to misunderstandings. And then there’s trouble. The faster ones will get by somehow. Don’t worry about them.”

Under my mask and helmet, I finally spoke, “Let there be noise.” I pressed the start button. And there was noise! I gave it a few blasts of the throttle to warm it up even more. No car had ever been louder and more ferocious under the tutelage of my right foot. I noticed the pained face of a spectator standing at the entrance to the pit (there was free access to all areas). She was covering her ears. Although she had fingernails painted Ferrari red, she apparently lacked the necessary resilience. In her defense, however, the overtones of this Porsche come very close to the sound of a circular saw collapsing. I stepped on the clutch (you only need it at the start) and used the paddle to put the car in first gear. Out into the pit lane. Keep the speed down to 60 km/h. Just a few more meters, a few more seconds – then it was time to raise the curtains on the first act of the play “Big Mouth or Bad Ass?” Time to go! I accelerated onto the long straight towards the Remus curve, slightly uphill with a left-hand bend that is taken in full. The very first, almost reassuring realization: The thrust is enormous, but it doesn’t knock my socks off right now. I don’t want to brag, but anyone who has had the fastest production supercars under their butt lately, like me, is used to a lot. The 769-hp Lamborghini Aventador Ultimae, for example, shoots from zero to a hundred in 2.8 seconds. This Porsche, I would think, does not. But acceleration isn’t everything. In a race car, you make up time during deceleration and in the corners. At 1,245 kilos, the RSR weighs around 300 kg less than a production supercar. The lower weight and the significantly more powerful brakes allow for full throttle up to about eighty meters before the entrance to the corner. Slicks, wings, diffuser and a chassis as hard as the asphalt itself then take you through the bend as if on rails. Another one hundred and fifty meters to the Remus hairpin. Don’t overdo it in turn one. On the brakes, downshift from fifth gear to first and round the corner at a maximum of 70 km/h. The pros aren’t any faster. Now the next long straight, speed of 240 km/h, leading to a steep right-hand bend. In the braking zone, a Mercedes-AMG GT3 pushed its way past me. The temptation to stay on its heels was great. Don’t do it, I told myself! No sooner was the Mercedes gone than I suddenly had a whole pack in my rearview mirror. The Brit in his 996 Porsche and a couple of Ferraris in tow. They all had knives in their teeth! Of all places, they just had to come along before the most difficult part of the track: two left-hand corners with a short straight in between, followed by a right-hand bend leading up the hill. I stayed on the line, expecting a jostle from behind at every second. It was wearing on my nerves. I deliberately braked early before the Jochen Rindt curve and let them pass. First lap completed.

The Red Bull Ring (formerly the Österreichring) was once the fastest Grand Prix circuit in the world alongside Monza and Silverstone. But it has long since ceased to be so. After several reconfigurations, the circuit no longer offers a single curve that can be driven through smoothly. It’s quite an arrhythmic affair, but that’s precisely why it’s so challenging to drive. Finding the right line and the perfect moment to accelerate out of the turns is a real problem. But I still had nine laps to go, and it felt better and better every time. Because, as P. said, the RSR is a good-natured race car. It’s so masterfully balanced, with neutral steering and no nonsense when exiting a corner. You can go over the curbs with it, as I did on lap six (albeit involuntarily), and nothing happens. Soon I was revving the gears all the way to the max (9,500 rpm, except for sixth gear, which would have been unbearable without earplugs) and moved the braking point closer and closer towards the entrance of the corner. I thought to myself: Racing is a cinch, isn’t it? The main thing in this car is willpower. And then I thought: You just have to clench your butt cheeks together tight towards the end of a long straight and stay on it as long as you can, even if you can already see the whites of the eyes of the spectators in the stands and think it was an exciting but short life. Stay on it! Thankfully, reason set back in just in time: Don’t overdo it, the RSR doesn’t have ABS, remember? Under no circumstances should you step on the brakes with an elephant’s foot. You need a good feel for it. Of course, even this race car has its limits in fast corners, but those limits are at a height attainable only by Andean condors or people like Kevin Estre, that marvelous French racing driver who couldn’t care less whether he was driving the RSR on asphalt or on grass. Three laps before the end I suddenly saw – would you look at that! – P. in his prototype in the rearview mirror. I thought he was going to bag me on the Schönberg straight, why should he linger behind me bored to death at my slow pace? But he stayed behind me – oh, he was a wily one! – watching me. Don’t tense up now! Keep doing your thing, I told myself. Don’t let yourself be rushed into any mistakes. That might be just what he’s waiting for. In the second-to-last lap, approaching the Rindt curve, he overtook me after all. Came in from the right and immediately turned left onto the racing line. I had that speed demon right in front of me, and I still dream of the sight. With hair-raising speed, he initiated the necessary preparations for the passage through the Rindt curve, and when I turned in, the 333 was already taking the first meters of the home straight under its wheels.

Tight squeeze, take two:

Ferrari 458 Italia GT2

When I returned to the pits a lap later, P. was already waiting for me. I was sweating profusely and would have liked to rest for ten minutes – and process the impressions. But that wasn’t what P. had in mind for me. He raised the pressure. “How was it?” he asked me only briefly. “Not bad, I think.” “Okay,” he said dryly, without giving me the slightest feedback. I should just keep my crash helmet on, he said, because the Ferrari 458 was ready and waiting. So I crouched down into the next tight squeeze. The same cramped conditions as in the Porsche, but at least this time the seat was adjustable. One of the Brit’s mechanics (who was still on the track in the 996) strapped me in and pushed the steering wheel with the buttons and the display closer towards me. Then the same procedure as in the Porsche: Push the button. Engage the clutch. Shift into first gear. Start rolling. Act Two can begin. The roar in the cockpit of the Ferrari 458 Italia GT2 is more intense. The Italian car has a deeper sound than the German one. Disreputable, dirty, vulgar. It’s the porn star at the Ring. But FIA has emasculated it, reduced its original impulsiveness. The 4.5-liter V8 produces 100 hp less on the dyno than the production 458, namely 464. This – quite controversial – intervention in GT racing is called “balance of performance”. To ensure equal opportunity, the air supply to more powerful cars (the Porsche RSR is one of them, too) is restricted. And you can sense that more should be possible on the straight. But even the longest straight ends at some point, and then you feel it so much more. Although it weighs the same as the Porsche, the Ferrari feels lighter, more agile, more nimble. It reacts more sensitively to your steering. That sounds good at first, but it’s not necessarily an advantage for anyone driving it for the first time. Because the Ferrari (no ABS, but traction control) is the more nervous car as a result. It’s a similar story with the throttle response, which is much clumsier than in the Porsche. On two occasions, I had a hard time accelerating out of a corner. Not because the rear end threatened to break loose, but because a brutal jolt went through the car that threw my head back and took away my view of things for two seconds. The biggest difficulty, however, were the other drivers. There was hardly a lap in which I could do my work undisturbed. Sometimes my gaze was focused more on the rearview mirror than ahead of me. Even Enzo Ferrari’s famous words didn’t help: “What’s behind you doesn’t matter.” I became nervous and confused. Slipped off the brake pedal at 230 km/h. Fortunately, there was no one directly in front of me. Where was P.? When would he come flying by in his exotic red car and check out how I was doing out there? But he didn’t show. Probably he was standing at the pit wall. What would be the best way to impress him the most? Quite simple: brake as late as possible for the Niki Lauda curve at the end of the home straight. With unparalleled ambition, I bit into this task lap after lap. Back in the pits, I got out and tore the helmet off my head. I was sweating like the reformer Jan Hus at the stake in Constance and poured myself half a liter of water. “How was it?” was all P. asked me again. “I think I had it reasonably under control,” I answered. In response to which he quoted Mario Andretti, the 1978 F1 world champion: “If everything seems under control, you’re not going fast enough.” Have I ever had a better motivator?

The powerhouse:

Porsche 996 RSR

He gave me five minutes. The Porsche 996 was already lurking behind me, a twenty-year-old Le Mans veteran. The car had been at the start of the endurance classic four times. 3.6-liter six-cylinder boxer engine, 409 hp, just over 1,000 kilograms, sequential six-speed transmission with a huge metal rod as a shift lever. I was in for some serious manual labor. A downright spacious cockpit compared to the other two. And a round, completely normal steering wheel without any buttons and switches. The Brit explained the finer points to me while I was already wearing my seat belt. “Have fun,” he then said and patted me on the shoulder. I was now riding out for the third time and felt like a veteran. The sound was insane. The familiar bass sound of a 911 – amplified a hundred times. Shifting up, I tore through the gears without using the clutch. The clutch was required on the downshift, however. I thrust the shift lever forward with considerable force. At first, these gear changes seemed to me to be an act of mercilessness, even cruelty towards the car. It seemed downright brutal, and I had the strange feeling that I wasn’t driving the 996 but torturing it. This made me feel all the more guilty because the car, which has ABS but no traction control, is such an immense joy to drive. Unlike the 991, it lets you sense its limits. You feel the road, and when it starts to slip, it doesn’t mean it’s all too late. You can stabilize it and keep it on course by steering and accelerating. I felt very comfortable. Even the traffic was stressing me out a little less by now. But I already had thirty laps under my belt and was pretty exhausted. My concentration was perhaps not at its best either, and I was dreading the 333. After the end of the stint I got out of the Porsche and approached P. I assumed that, for the third time, he would again just ask me briefly how it had been. But I wasn’t in the mood for that anymore. I was determined to ask it myself this time (“How was I?”). As if I were Leonardo DiCaprio after a sex scene with Scarlett Johansson in a Hollywood movie. It didn’t come to that. Before I could open my mouth, he gave me the thumbs up: “Great job, really!” Well, if P. says so! Three words that refueled me, gave me strength for the last and most difficult act. The Brit was also there: “Well done!”

A mansion of rock:

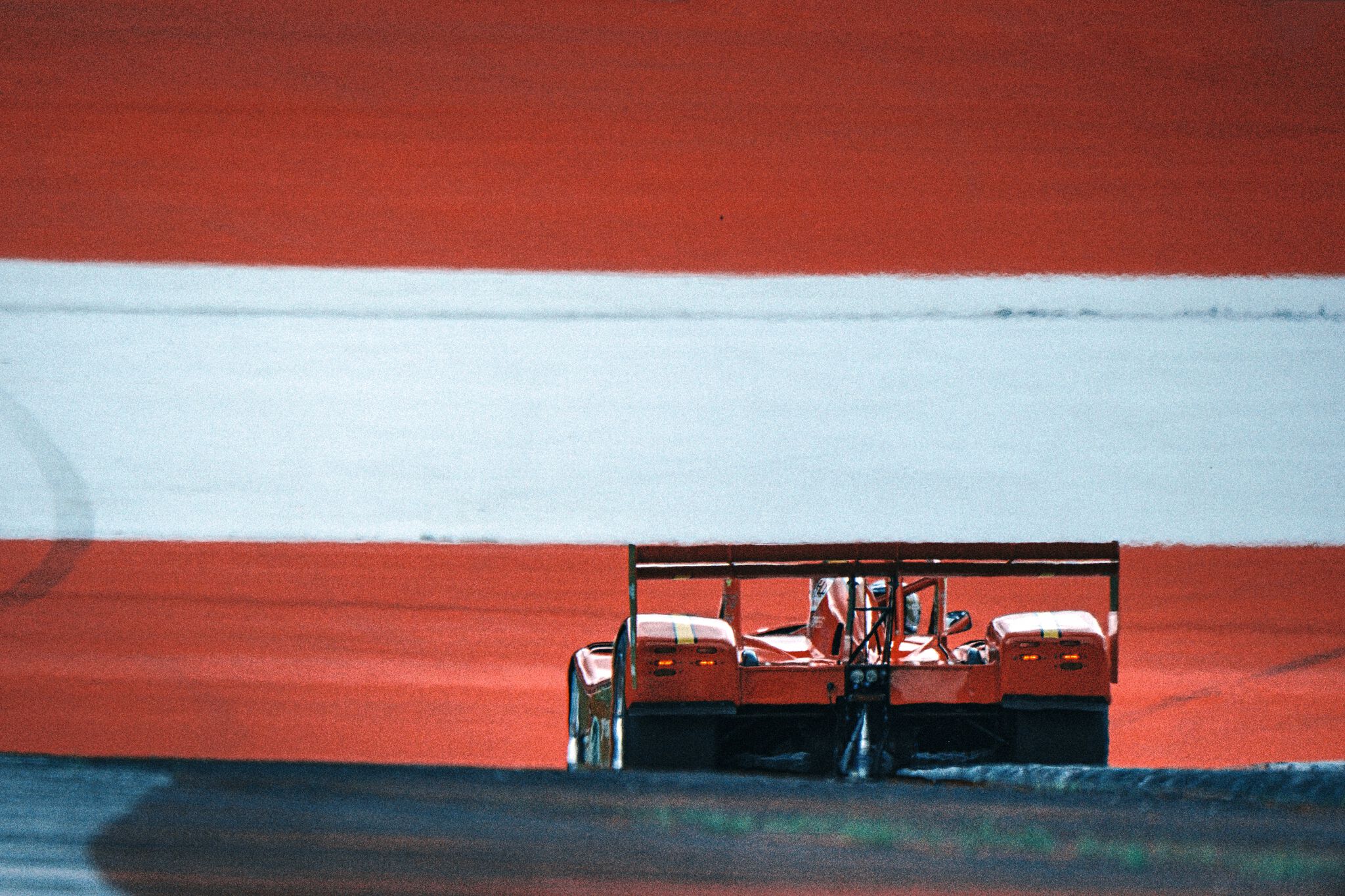

Ferrari 333 SP

As for the Ferrari 333 SP, you don’t so much get into it as you climb it like a rock. Right foot on the broadside along the cockpit and slide in with the left – there’s no other way. P.’s tiny seat pan, which was additionally embedded in the bucket seat to elevate the driver, had been removed so that I would have enough room. When I had settled in and was strapped down, it seemed to me as if I were dreaming. Could it really be true that I was sitting in the very prototype sports car that had won the 1998 12 Hours of Sebring and 24 Hours of Daytona and finished third in the LMP1 class at Le Mans with drivers Mauro Baldi (ex-F1), Giampiero Moretti and Didier Theys? Could it really be true that I was about to roll out of the pit lane in a car of which only forty-five had been built and which had the value of a lavish mansion in the most upscale neighborhoods of this world with, let’s say, outdoor and indoor pool, library, billiard room, five sleeping rooms and an asking price in the double-digit millions? But I knew wasn’t dreaming because I could feel my temples throbbing against my helmet. My nervousness was heightened knowing how difficult it was to handle this finicky five-speed sequential gearbox. P. had drilled the essentials into me beforehand like a mathematical formula. At the end, he said, “You can break a lot pretty quick.” How reassuring.

Starter on. Fuel pump on. Engine on. As I said, the twelve-cylinder from the F1 Ferrari (1992 model) has a terribly beautiful sound! 641 hp at just 860 kilos and a top speed of 368 km/h! Unfortunately, there’s not a straight line long enough here to drive it out, you’d have to be at Mugello or Barcelona. But what am I talking about top speed here, I already failed while pulling out. You can’t get going below 7,000 rpm, and the engine died twice. When I finally got on the track, I had a hard time shifting gears. Some twenty-five years ago, this Ferrari was one of the first race cars with a sequential transmission. Zero electronics. When you shift up, you can’t just rip through the gears like you can with a sequential transmission of later design. You have to lift the throttle. But if you do this inadequately, as I did on the first few kilometers, the transmission locks up. Downshifting then requires double-clutching and blipping the throttle, and timing is of the essence. Three sequences must be performed simultaneously: You have your right front foot on the brake pedal, make the rocking motion on the gas with your heel and shift down. This has to fit exactly and be lightning fast. My concentration was focused eighty percent on not ruining the transmission, on not pulverizing it. By the time I was halfway there, more than half the distance had been covered, and I only had two laps that I would say were okay and in which I could assess the potential of the Ferrari 333 SP. Above all, it’s not the beast you think it is when you experience it from a spectator’s perspective. On the contrary, since much of its weight rests on the rear axle, something akin to peace emanates from there. There were no nasty surprises. Those wide tires work wonders for an intimate relationship with the road, and the large underbody and wing give you some real downforce. I soaked up the Schönberg straight. The noise of the F1 engine mingled with the rush of the airstream and gave me a supernatural experience. I braked later than in the three previous cars. No problem with the lightweight Ferrari – and not for a second did I think that ABS or traction control would be helpful. I would have liked power steering, however, because my forearms are still sore as I write these lines. Then the dream came to an end. I got out of the Ferrari. P. was already waiting in the pit lane. He had his crash helmet on, leaned into the cockpit and put his seat pan back in place. “That was just the beginning,” he said, “we’ve established a good foundation here. The next time, wherever that may be, we’ll do it with clocked lap times, okay?”

Text:Kurt Molzer

Photos: Matthias Mederer & Marko Knab/ ramp.pictures

ramp #58

As a high-impact multimedia brand that takes an all-encompassing, end-to-end approach to publishing, ramp is an absolutely authentic expression of quality, integrity and excellence. Its trailblazing luxury magazines, recognized with numerous awards over the past 15 years, have been celebrated for their cool and unconventional, not to mention inspiring and pioneering style, since day one.

ramp, the lavish and beautifully designed coffee table magazine, celebrates the enthusiasm for cars and driving in a passionately subjective, personalized fashion.

Immediate, authentic, intense. Fresh perspectives, avant-garde imagery, with a fine feeling for nuances and the right dramaturgical mix. Always new, always stimulating. Automotive passion infused with a lust for life. The automobile in new, exciting and intense contexts, precisely tailored to the relevant target group, presented in relation to music and fashion, culture and lifestyle, design and art, science and philosophy.