Fifty years ago, a super sports car was invented that still sets the standard today. Also in matters of pronunciation. We’re talking about the Lamborghini Countach, of course.

To avoid embarrassment, let’s practice pronunciation first. It’s worst among the classic car admirers on the American West Coast, who say “KOON-tack” or perhaps “KOON-tash”.

Back in February 1971, the prototype still didn’t have a name. The house of Lamborghini had the tradition of using words from the world of bullfighting for its cars. The first was the Miura, followed by the Islero, Espada and Jarama. When it was picked up from the Bertone factory in Turin by Lamborghini test driver Bob Wallace, the yolk-yellow 1971 prototype ran only under the code number 112, later LP 500. The car was set to travel over partly snow-covered Alpine passes to the Geneva Motor Show. During the final polishing up ahead of departure, a worker exclaimed, “Contacc!” Anyone who is slightly familiar with the Piedmontese dialect will know this as an exclamation of astonishment and delighted surprise, pronounced “KOON-tahsh” and meaning something like “Wow!” or “Awesome!” or “Look at that!” The company was comfortable enough to transcribe the spontaneous name for the baptismal register as “Countach”.

The decision to resort back to bullfighting for the Lamborghini nomenclature is another matter. Arguably the most famous of all fighting bulls was Murciélago, and his story is worth a brief digression. According to legend, and Wikipedia, Murciélago fought with such passion and spirit that the crowd called for his life to be spared. Bull breeder Antonio Miura then bought the famous bull and sired him with seventy of his cows. Though it seems somehow distracting that the better half of a fighting bull is simply called “cow”.

But we should stop with all this cattle talk. Their names are always being re-excavated from history, while in the modern era they keep being slaughtered in the arena. Audi had nothing against the Aventador. Urraco, Gallardo, Diablo, Huracán – all incredibly courageous fellas, but the hybrid models now have vegetarian names . . . the new age treads lightly.

Ferruccio Lamborghini is the starting point of legends, all of which are set in Emilia-Romagna. Beginning in the mid-1950s, the region around Bologna became known as a hotspot for technology, design and production. And there are literally hundreds of marvelous stories about this steaming hotbed of creative power, globally unrivalled, and all of them somehow true. Like the legendary rivalry with Enzo Ferrari, if only because of the genius designers, coachbuilders and engineers (all of them in their mid-twenties) that the two were constantly poaching from each other. Lamborghini was eighteen years younger than Ferrari, who already had thirty years of racing experience under his belt when the factories began revving up again. Lamborghini’s astrological sign was Taurus, the bull. Once, during a visit to Spain, he happened to see a corrida – which inspired him as to the model names. Enzo Ferrari ended up with the prancing horse as his heraldic animal through historical coincidence as well.

Ferrari was on its way to world fame in Formula 1 when Lamborghini expanded its business from tractors to GT cars (the motives ranging from a smart vision to disdain for neighboring Ferrari’s unreliable rattletraps). Lamborghini also thought it made no sense to get bogged down between Formula 1 and customer cars. By the time the idea of a super-powerful mid-engined car took shape, Lamborghini had already set a landmark with the Miura. And here it was: an absolute work of art consisting of a space frame powered by an aggressive V12, all hidden in a design more radical than anything that had come before. The Countach would make all future sports cars and supercars look like mere derivatives, increasingly mired in scoops and slugs and diffusers and spoilers until you could maybe drive 450 km/h without taking off like a Concorde. But you’d still look pretty drab parked next to a Countach.

It should also be said that the “one-box” shape (nearly seamless from end to end) didn’t just fall out of the sky; it had already been hinted at in Bertone prototypes. The young man behind it all was Marcello Gandini, who set to work with clarity and focus. Though speaking of clarity: even Gandini couldn’t quite get past air scoops and the NACA ducts known from aviation at the time, and – horribile! – he even had to acquiesce to exterior mirrors. Every detail was ultimately subordinated to the love of geometry (and here especially the trapezoids). The real eye-catchers were, of course, the first scissor doors on a production car – fantastic to look at, rising dramatically above a 107 centimeter roof. Which immediately makes you wonder what it’s like getting in the car – and then? Here, as always, it pays to have a good friend to help you out.

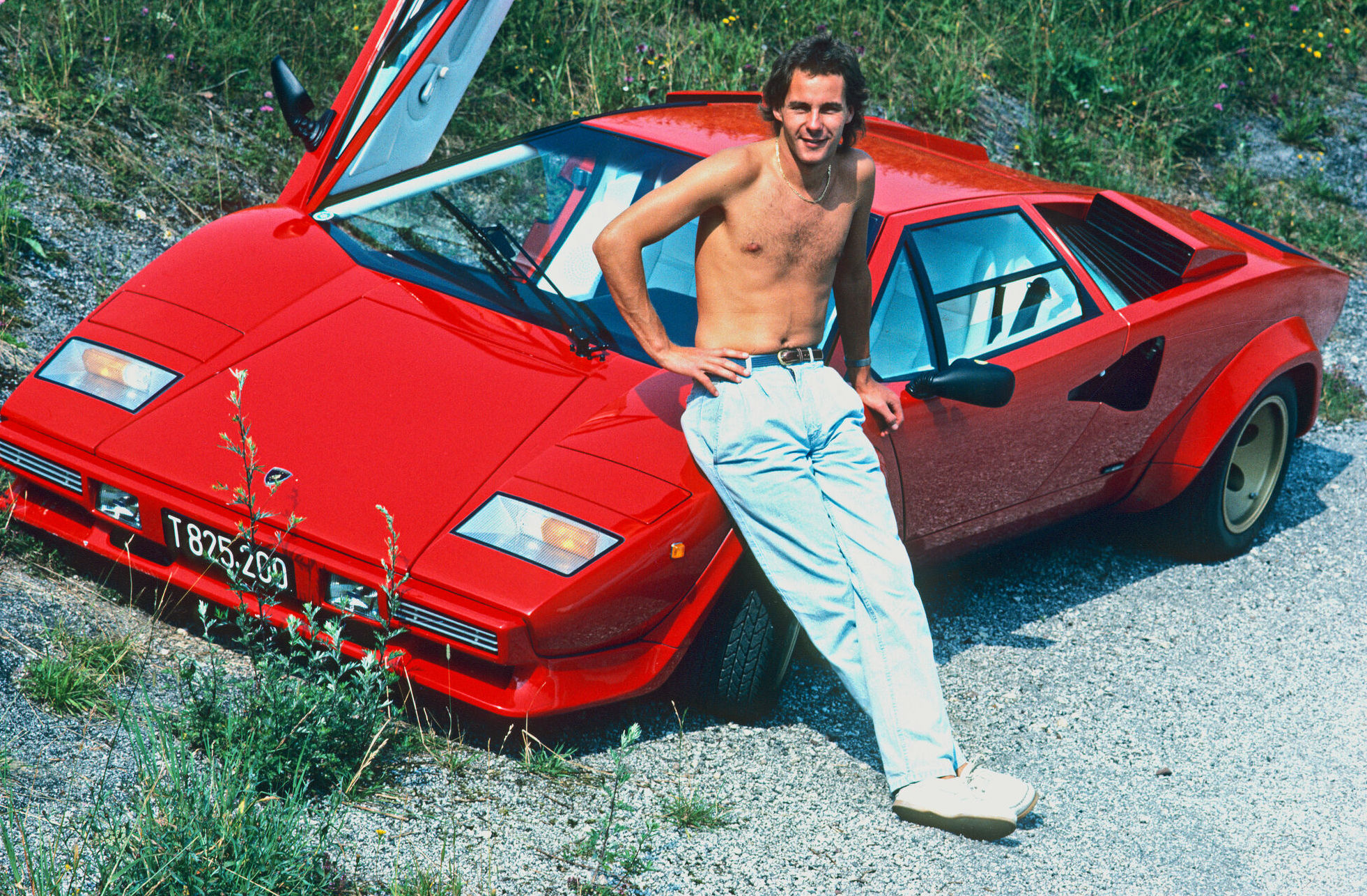

Gerhard Berger purchased his Countach in 1986 – that was the production year with the most state-of-the-art technologies in the model – as a 5.2-liter, 455-hp Quattrovalvole. Let us repeat that, but more slowly: four hundred and fifty-five aitch pee! That was a lot twenty-five years ago, and it all came without the soft hum of the electronic generation. A gear change was a gear change, my neck still hurts today. 1986: that also means fifteen years after the prototype on the Bertone stand in Geneva, thirteen years after the start of series production. Ferruccio Lamborghini had long since left the company and was producing his own wines (surprisingly down-to-earth, in the medium price segment).

At the height of its technical development, the Countach looked even more dramatic than in its early days. By contrast, the Testarossa from Ferrari that had since come out looked rather benign, a car for driving to the movies. But no one should take that personally. I had the delightful aspiration to meet Gerhard Berger and his Countach in their natural environment, which was then (and now again) in Wörgl, Tyrol. Gerhard was in his third Formula 1 year (in a Benetton BMW) and hadn’t yet won a Grand Prix. Fortunately, this was rectified at the end of the season with a victory in Mexico (ahead of Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna, just to set the memory straight). A fundamental experience was, of course, getting in and out of the car. You were meant to slither into the seat, then crawl out when no one was watching.

The immediately obvious, incomparably new thing about the Countach – and that remains sensational today and will do so the day after tomorrow – was the outrageous, unrelenting design, which from the very outset wasn’t subordinated to function. Design and technology each amplified the other. Sure: everything would have been pointless without the perfect skeleton, and you can put this tubular frame in any museum of applied arts in the world as it is. If someone is into trapezoids, a real freak about them, he’ll start counting, and with each turn there will be more: hidden trapezoids, implied trapezoids, exaggerated trapezoids, second- and third-order trapezoids. I came up with twenty trapezoids, and if I started counting again, I’m sure it would be twenty-one or twenty-two. And when a small – unfortunately unavoidable – attachment was needed above the engine for ventilation, it turned into a repository for the Congregation of United Carburetors: six twin Webers synchronized in wicked pops, crackles and a raspy roar, and from below the ornery Murl in its growling fury.

Fuel consumption was still a matter of honor back then: not even ten miles to the gallon in normal traffic, more with Gerhard Berger at the wheel. Only about a hundred Countachs were built each year, so at least that kept the ecological footprint small overall. But it also means that some two thousand cars were built over the entire production period. That was no longer “exclusive” and also explains the return on investment for fans of classic cars: as an owner of a Countach, you didn’t end up in the poor house, but you didn’t gold-plate the tiles in your garage either.

The 5.2-liter V12, as mentioned before, produced 455 horses of power, went from zero to a hundred in 4.6 seconds and had a top speed of just under 300 km/h, which still cuts quite a figure today. Berger told me matter-of-factly, however, that beyond 250 km/h the rear end becomes so light you have to grit your teeth, and if you give it a good thrashing upwards of 300 km/h, the brakes are screwed.

“When you’re driving fast in the rain, you’ve really got your hands full,” Gerhard told me, though he thought you should still do it every now and then – as well as provoking an abrupt load transfer during fast cornering – just for the sake of experience: “It’s out of this world!” I politely declined his offer for a first-hand experience in advanced driving. That evening, we merely drove to a friendly foreign country (that was Germany at the time) to give the red fella a bit of a faster go. Tearing through the short gears, with that killer thrust from 100 km/h to 150 km/h and from 150 km/h to 200 km/h, and how it pushes into your entrails, that was still completely new and incredible back then. The memory remains unparalleled, in part because today’s modern supercars have so many on-board electronics, which totally softens the experience. The g-forces are still the same, of course, but unless you’ve got Mike Tyson’s neck, your head will remain firmly planted in the headrest.

The following may seem a bit out of place from today’s point of view, what with Covid, political correctness and the sort of camaraderie out there on the road. Let’s just see it as the fond memory of a Dutch tourist on holiday in Tyrol.

We had a different way of doing things back then, were less respectful in our choice of words. When I read today that the mere sight of our red Countach caused “the Dutch tourists to steer their old clunkers straight into the ditch,” I am a bit surprised at my lack of tact. But it is a fact that they, the Dutch tourists, lacked a certain composure when the Countach came flying toward them out of a bend on a mountain road. We could only observe the agitation at a delay, watching the reactions of the nervous Opel drivers in the rearview mirror, once with a headlong dive into the greenery. We felt like some mean Dutch tourist–eating machine. I still remember wondering how many Dutch tourists there were in Tyrol and how they could all be on vacation at the same time. What were things like back in Holland? Who was keeping the country up and running with everyone on holiday? Of course, there is no point in asking these sorts of questions today.

We won’t bother with currencies and exchange rates here, instead preferring to leave the following pleasant image: two million schillings, that’s how much the Countach cost in Berger’s home country and mine. In any case, it was quite a considerable amount of money thirty-five years ago. Gerhard, in his logical, clear manner (astonishingly similar to Niki Lauda), was able to explain quite well why he wanted this car, the most beautiful car in the world. “Cars are my whole life. Everything I am and have in life has to do with cars.” Not that he thinks that makes him special, but that’s just the way it is, you shouldn’t fool yourself, as he said. It only makes sense, therefore, and is completely natural that, as soon as the opportunity arises, a guy like Berger would want to buy himself the most beautiful car in the world. “It’s actually the same for an accountant,” Gerhard said. “After all, an accountant will also want to own the most beautiful ballpoint pen.”

ramp #57 – Really?

In this issue of our magazine we are simply engaging in a stimulating conversation. We ask the question “Really?” and allow it to unfold in a playful range between indignant outrage and thoughtful reflection. Because not only is everything connected, it also is the relationships between things that make them what they are. Or something like that.

Text by Herbert Völker for ramp

Photos by Didi Sattmann · ramp.pictures