Strict confidentiality was required when Porsche was researching turbo technology for racing use. The revolution in engine design secured Porsche race victories in the 1970s. And paved the way for its subsequent use in series production.

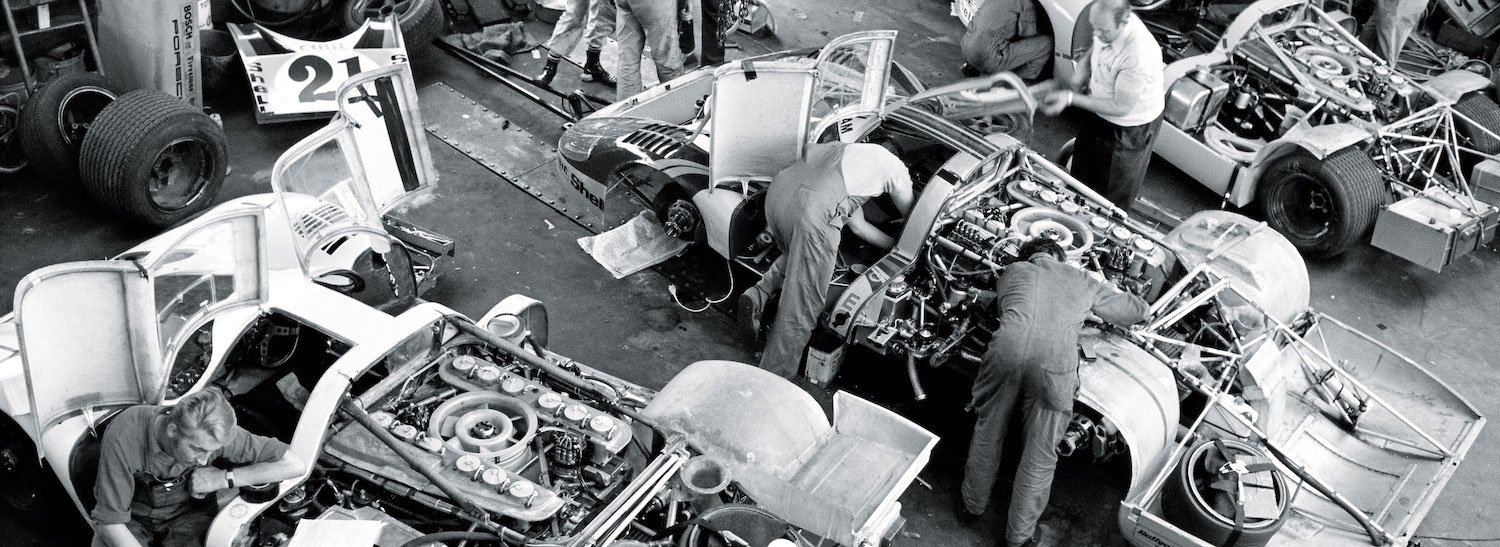

Teloché near Le Mans in the early 1970s. Here in a little workshop, the Porsche team is preparing for the 24-hour race. It’s almost dark when engine specialist Valentin Schäffer meets Head of the Motorsport department at the time Ferdinand Piëch and Head of Testing Helmuth Bott. “I remember it well,” relates the now 92-year-old Schäffer when we meet him at the Porsche Museum. “Piëch asked me: ‘What are your thoughts on a Turbo? As you know, we want to enter the Can-Am series.’”

Porsche was incredibly successful with the 917 in Le Mans and in the World Championship for Makes in 1970 and 1971. However, the governing body’s decision to only accept engines with maximum displacement of three liters meant Porsche would not be able to compete in the following season with the 4.5-liter engine. Hence the switch to the Canadian-American Challenge Cup. It was a paradise for the engineers as there were virtually no limits for their imagination and engineering expertise. Some of the competitors were competing in 800 PS, 8.0‑liter V8 engines, so Porsche needed an alternative to the tried-and-true 4.5‑liter V12 naturally aspirated engine in the 917. Experiments with a significantly heavier V16 power unit came to nothing because the handling wasn’t good enough. The solution was perhaps a turbo engine, but nobody at Porsche had any practical experience in this field.

This technology was not even new – the first patent was filed in 1905. In the 1960s and 1970s, turbochargers were used in truck diesel engines, occasionally in automobile models for the road, and in oval track racing. The technology was not yet fully developed.

The turbocharger principle is easy to explain: the combusted air-fuel mix flows from the cylinder into the exhaust system, powering a turbine on its way. This is connected to a compressor wheel on the inlet side by a shaft. This pushes fresh air into the engine’s combustion chamber under pressure, allowing for more efficient combustion. Following the encounter in Teloché, the responsible engine developer Hans Mezger (1929–2020), Valentin Schäffer, and other engineers formed what would now be called a think tank. The 4.5-liter naturally aspirated engine in the 917 was to be fitted with two exhaust gas turbochargers to deliver up to 735 kW (1,000 PS). The team delivered some pioneering work – thereby creating the basis for subsequent use of the turbo engine in series production. Confidentiality was a top priority.

The turbochargers were sourced from a supplier who could demonstrate experience with truck engines. The initial testing on the test bench at Porsche was sometimes a little odd. Mercury columns were used to measure the boost pressure. “The first time we left the engine running and stepped on the gas, it all came flying out of the tubes and rained on our heads,” remembers Schäffer, laughing. “Not something you can imagine happening today.”

On July 30, 1971, works driver Jo Siffert performed the first kilometers in an open-top 917/10 with a turbo power unit on the Hockenheimring – a historic day. “The test-drives presented us with new tasks,” explains Schäffer. “The drivers sometimes drove straight ahead on the corners or spun out because the power upon acceleration kicked in so unexpectedly.” These surprises were down to what’s known as the turbo lag – characteristically delayed responsiveness upon accelerating. It always took a moment for the pressure to build up on the inlet side, but then the power would unfold with brute force. Not a problem on oval racetracks where you’re driving at full throttle most of the time. But on circuits with tighter corners and a lot of load changes, the turbo needed to be tamed and made manageable.

The Porsche engineers came up with the practical solution of a bypass valve, otherwise known as a waste gate. This opens when the boost pressure is too high and enables the exhaust gas to bypass the turbocharger. On the one hand, this spares the engine, and on the other, it allows the turbo lag to be better regulated. This means turbochargers can be used that generate enough boost pressure at low speeds. Porsche was the only manufacturer to venture to experiment with turbo in the 1972 Can-Am series. American race car driver and engineer Mark Donohue was heavily involved in the development test-drives. In the turbo engine’s race premiere in a 917/10 Spyder at Mosport Park in Canada on June 11, he beat the lap record by four seconds at the first attempt – that’s huge in the world of motorsport.

Donohue rolled into the pit with a defect after 19 laps. Schäffer was quick to identify the problem. “A caught tension spring had caused a flap to get stuck. I struck the axle with a hammer and the spring opened again,” reports the former Porsche engineer. Donohue came back from being two laps behind and ultimately finished in second place. He had to bow out of the subsequent races due to injury. Substitute driver George Follmer won his debut at Road Atlanta. In all, the 917/10 Spyder racked up six wins and clinched the title in the 1972 Can-Am series.

The 917/30 continued this success story the following year. The further developed air-cooled, 12-cylinder engine with displacement of 5.4 liters delivered power upward of 800 kW (around 1,100 PS). The driver had a boost controller in the cockpit to regulate the boost pressure. This was switched to high at the start of the race and then lowered in the course of the race. This took the strain off the engine and saved fuel. “Power was never the problem with the turbo engine, but we had to keep the temperature of all the components in check,” says Schäffer. Donohue won six of the eight races in the 1973 Can-Am series to clinch the championship title. One year later, Porsche only competed in one race as the governing body had introduced a fuel consumption limit. The series came to an abrupt end after this season anyway, when the sponsors withdrew due to the oil crisis and a recession in North America.

From 1972, private racing teams lined up in the 917 at the Interserie – the European version of the Can-Am series. In 1975, Porsche was only competing in the Interserie. This year, the 917 achieved a world record in the rousing finale. Intercoolers featured in the vehicles for the first time. These cooled down the very hot intake air. The higher density of the colder air increased the air charge in the cylinder, for increased power. On the 4.28-kilometer Talladega Superspeedway oval circuit in the state of Alabama, Donohue achieved an average speed of 355.84 kmh. and a top speed of 382 kmh. This record stood for 10 years.

Porsche was now focusing on the 911 again and exhaust gas turbocharging was incorporated into the 911 Carrera RSR Turbo 2.1. “We were able to apply many of our insights from the 917,” says Schäffer. The first test-drives with the approximately 368 kW (500 PS) 911 were performed on the Circuit Paul Ricard in the south of France in November 1973. In the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1974, the Carrera RSR caused a sensation as the first model in the World Championship for Makes to be equipped with a turbo engine: competing in the sports car class, Gijs van Lennep and Herbert Müller held their own in the face of the favored, significantly more powerful prototypes and finished in second place overall. “It was incredible. This had never been done before,” enthuses Schäffer.

The revolutionary turbo technology established by Mezger and Schäffer in motorsport served as the basis for the Porsche 911 Turbo unveiled in Paris in 1974. Hans Mezger encapsulates the fascination of what was then the most powerful production sports car in a nutshell: “The turbo engine kicks in where other engines conk out.”

Report by Bianca Leppert for Porsche (first published on newsroom.porsche.com)

Photos by Porsche/ Motorsport Images

![Is this the greatest racing film oat?

In “Ford v Ferrari”, one of the most important

moments comes when Ken Miles takes the GT40 out for a test run after it’s fitted with its massive new 7.0 litre V8. The scene captures a turning point in Ford’s effort to challenge Ferrari at Le Mans, with Miles pushing the prototype hard at Ford’s Dearborn test facility.

With his trademark intensity, Miles immediately feels how the car responds to the raw force of the 427 cubic inch engine. The sound, speed, and feedback through the steering wheel signal that the GT40 is finally becoming something special.

The moment isn’t just cinematic drama, it reflects real history. The big block 427 gave Ford the power it needed to fight Ferrari, and Miles’s deep mechanical understanding played a key role in shaping the car’s behavior on track.

Despite Ford pouring more than $25 million into the program, it was experiences like this, Miles sensing every detail from behind the wheel, that turned early prototypes into Le Mans winning legends.

( Media via “Ford v Ferrari” [2019] )](https://collectorscarworld.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)