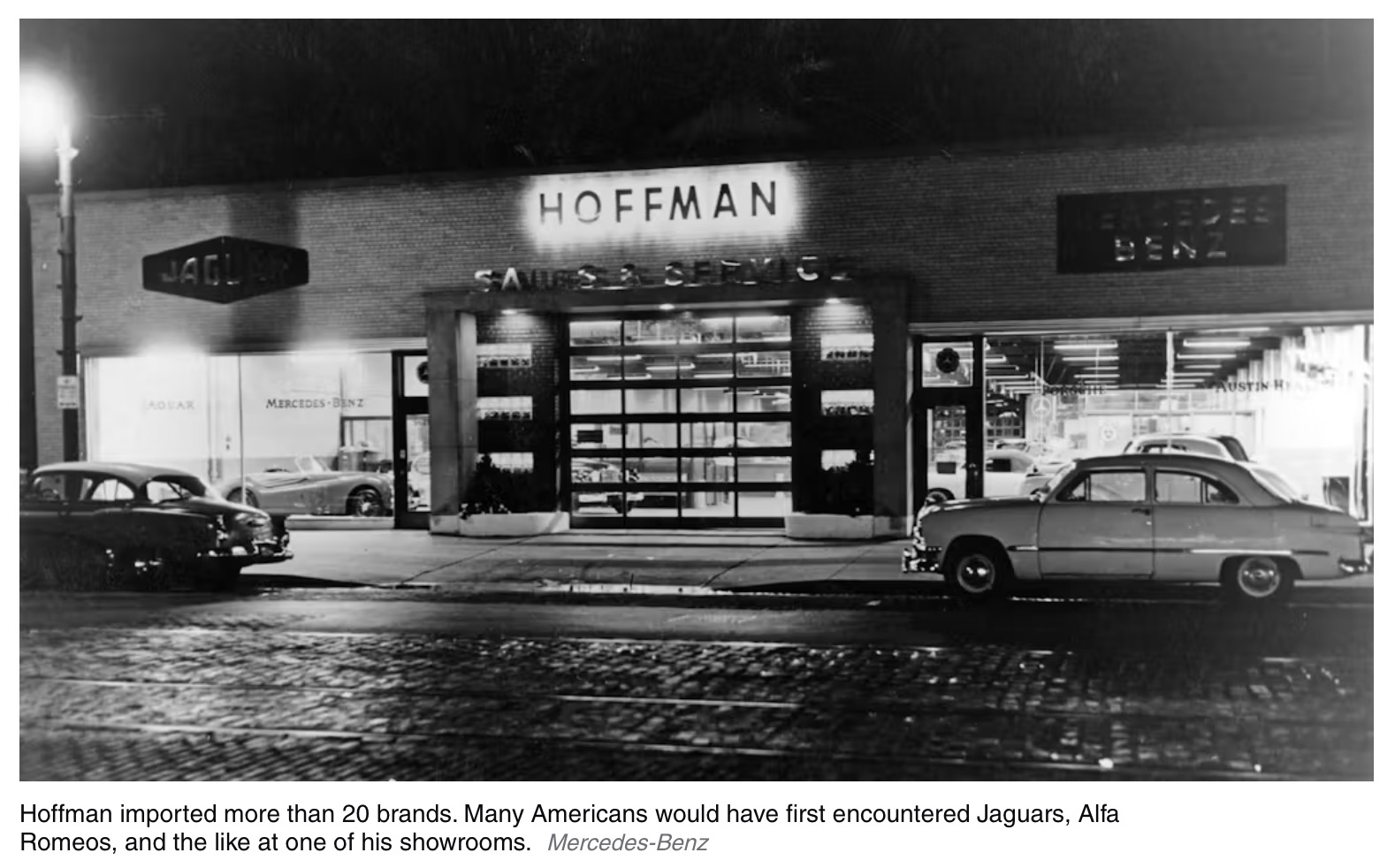

In 2013, the New York Times wrote about the demolition of a small 1950s automobile showroom on Park Avenue, which had happened, it reported, “almost without notice.” The dealership had been notable as one of the relatively few buildings in the city credited to the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright, but no one, it seemed, deemed it significant enough to mount a protest against its removal (the Times added that architectural historians considered it one of Wright’s lesser works). For decades, this small showroom had been the epicenter of enthusiasm for foreign cars in the United States thanks to the man who’d commissioned it, Max Hoffman.

From the late 1940s through the mid-1970s, Hoffman reigned over the importation of European cars to this country, becoming fabulously wealthy and somewhat notorious in the process. Then, he was gone. He lost control of BMW in 1975 and died just six years later.

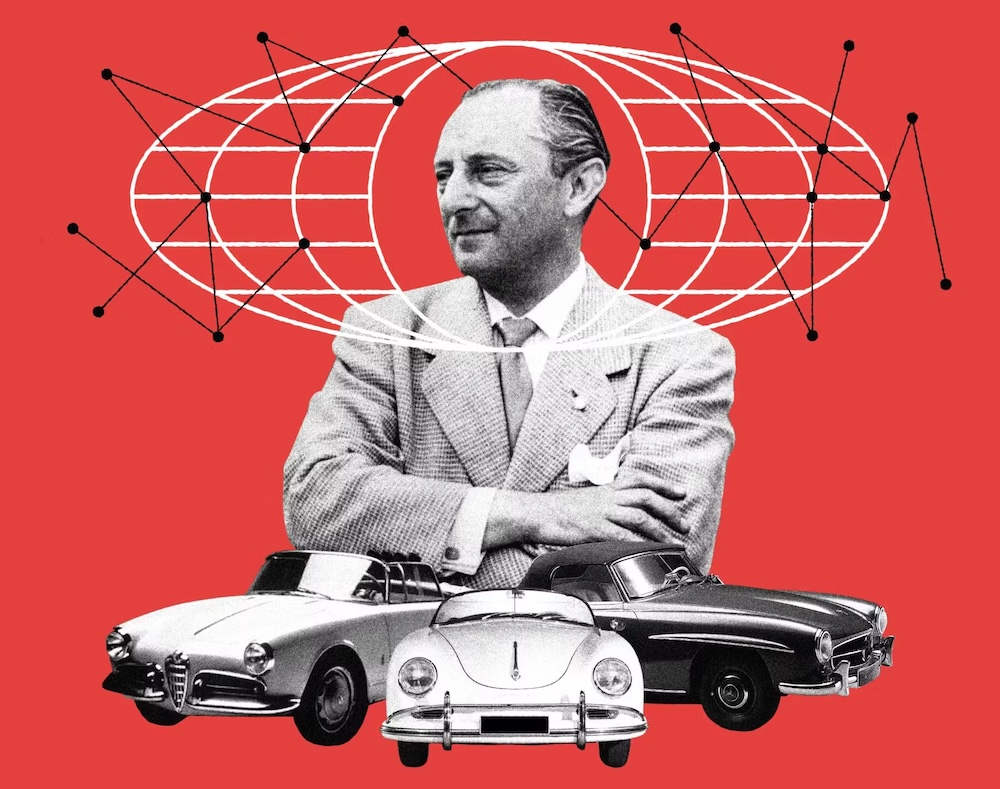

In the decades since, he has become a shadowy figure, resigned to the prehistory of the now enormous European manufacturers who do business in the United States. It’s become hard to separate myth from stranger-than-fiction fact: He was not, as some claim, Dustin Hoffman’s uncle. He likely did, over a meal in a New York restaurant, suggest to Ferry Porsche that his newfangled sports cars might sell better with a logo, resulting in the development of the brand’s famous crest. More important, Hoffman helped create and influence some of the most celebrated cars of all time, including the BMW 507, the Porsche Speedster, and the Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing.

“Most of the parade sports cars that we love today would not have happened if Maxie Hoffman hadn’t talked the factories into producing them,” said Bob Lutz, who worked with Hoffman at BMW.

Also incontrovertibly true: Many of the companies that did business with him felt cheated. “He was such a crook,” added Lutz, a longtime automotive executive who worked for carmakers on both sides of the Atlantic.

Amid the accomplishments and controversy, Hoffman himself remains something of a mystery. Perhaps that’s exactly how he wanted it, but we nevertheless spoke to those who knew him and dug through archives to learn more.

Life as a Refugee: “They Were the ‘Don’t Talk About It’ Types”

Max Hoffmann (he dropped the extra “n” in his surname in the United States) was born in 1904 in Purgstall an der Erlauf, Austria, a small town west of Vienna. He was part of a large family that included a half-brother from his father’s previous marriage, a brother, Kurt, and a younger sister, Risa. He and his brother spent summers with three first cousins, all around his age. “The five boys were very close,” said Gail Hoffman Storch, daughter of one of those cousins, John. “They would have such a good time, riding their bikes through the mountains there.”

Hoffman’s parents, Ida and Salomon, were both Jewish. Some biographies claim Hoffman’s mother was Catholic, but both Hoffman Storch and genealogical records produced by the Institute of Jewish History in Austria attest otherwise. That said, they seemed to consider themselves first and foremost proud Austrians. They spoke a highfalutin German, as opposed to Yiddish, the lingua franca of most Eastern European Jews, and even after immigrating to the United States tended to associate most closely with other Austrians. “You wouldn’t believe how snobby they were,” remembered Hoffman Storch. For his entire life, Hoffman dressed and sounded the part of a European gentleman, replete with fine clothes and—when he made enough to afford them—stately homes. “He was a man of excellent taste,” said journalist Karl Ludvigsen, who still uses a brass shoehorn Hoffman gifted him in the 1970s.

Like many a young European gentleman in the early 20th century, Hoffman fancied cars—his father, a successful manufacturer of sewing machines and then bicycles, bought him several. By his early 30s, he’d found his calling importing and distributing vehicles, selling Austrians everything from Pontiacs to Delahayes.

Unlike many dilettantes, Hoffman could drive fast. He competed first on DKW motorcycles and in the 1920s became a factory driver for Grofri, a short-lived Austrian manufacturer. Even as an older man in the United States, he competed to show the worth of his wares. He told Ludvigsen that he ran a hill climb in a Porsche so fast that a competitor, one Briggs Cunningham—the American sportsman who launched his own car company—claimed that the time must be false, so he ran it again.

Many automotive innovators from the early 20th century, including Morris Garages, followed a similar trajectory of bicycle shop to racing cars to selling them. Had Hoffman been born in England or the United States, we might be talking today about the genesis of an automaker. But this was Austria, and Hoffman was a Jew. In early 1938, Nazi Germany annexed the country. Later that year, many Jewish businesses were destroyed during what became known as Kristallnacht (“the night of broken glass”). Hoffman fled for Paris. There he continued his enterprises, but alas, so did the Nazis, and upon their invasion of France, he was forced to run again, this time to a monastery in Holland.

In these years, the United States had imposed strict immigration quotas, but fortunately for Hoffman, his cousin John had already made it there and was able to sponsor him and his mother. His brother Kurt and his only niece, Erika, remained in Austria and died in the Holocaust. His sister, Risa, survived by hiding underground in a nunnery in Italy. Hoffman rarely if ever seems to have mentioned the impact of the war on his family in interviews. Of his passage to the United States, Hoffman later told journalist Karl Ludvigsen that “they cooked the same kind of fish every day. It was terrible.” Unmentioned was the fact that his ship, the SS Mouzinho, had been specially commissioned by the U.S. government and Jewish aid organizations to bring over hundreds of desperate refugees, many of them children. The Hoffman family’s silence carried into their private lives. “There are [Holocaust] survivors who talk about it all the time and the ones who never talk about it,” recalled Hoffman Storch. “They were the ‘Don’t talk about it’ types.”

Hoffman arrived in June 1941 with such meager funds that he and his mother had to crowd into an apartment with their cousins. Within six months of their arrival, the conflict they’d escaped followed them, as Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and Germany declared war on the United States. Hardly the time to start a new business venture. Hoffman, however, discovered a niche: American women, newly employed in wartime production, found themselves flush with cash but had little to spend it on—even jewelry was hard to come by, as precious metals were deemed necessary for defense purposes. So Hoffman, borrowing $300 from a friend, started a business selling plastic costume jewelry. It was a hit. He told Ludvigsen that within one week, he’d booked $5000 in orders.

New York City is to this day filled with jewelry dealers, now in their second or third generations, who started in much the same way and kept at it. But Hoffman didn’t want to sell jewelry. He wanted to import cars.

Building an Empire

The most obvious question when it comes to Max Hoffman is, Why him? Why did this new immigrant, as opposed to someone more established, become the importer of record for so many prominent European brands? Why did those brands need anyone at all? Yet those very questions betray a certain bias—one that Hoffman played an outsize role in shaping.

“You need to bear in mind… that imported cars weren’t really a thing until Max Hoffman was bringing them here,” said journalist and historian Jackie Jouret, who has written several books focused on BMW, including Max Hoffman and BMW.

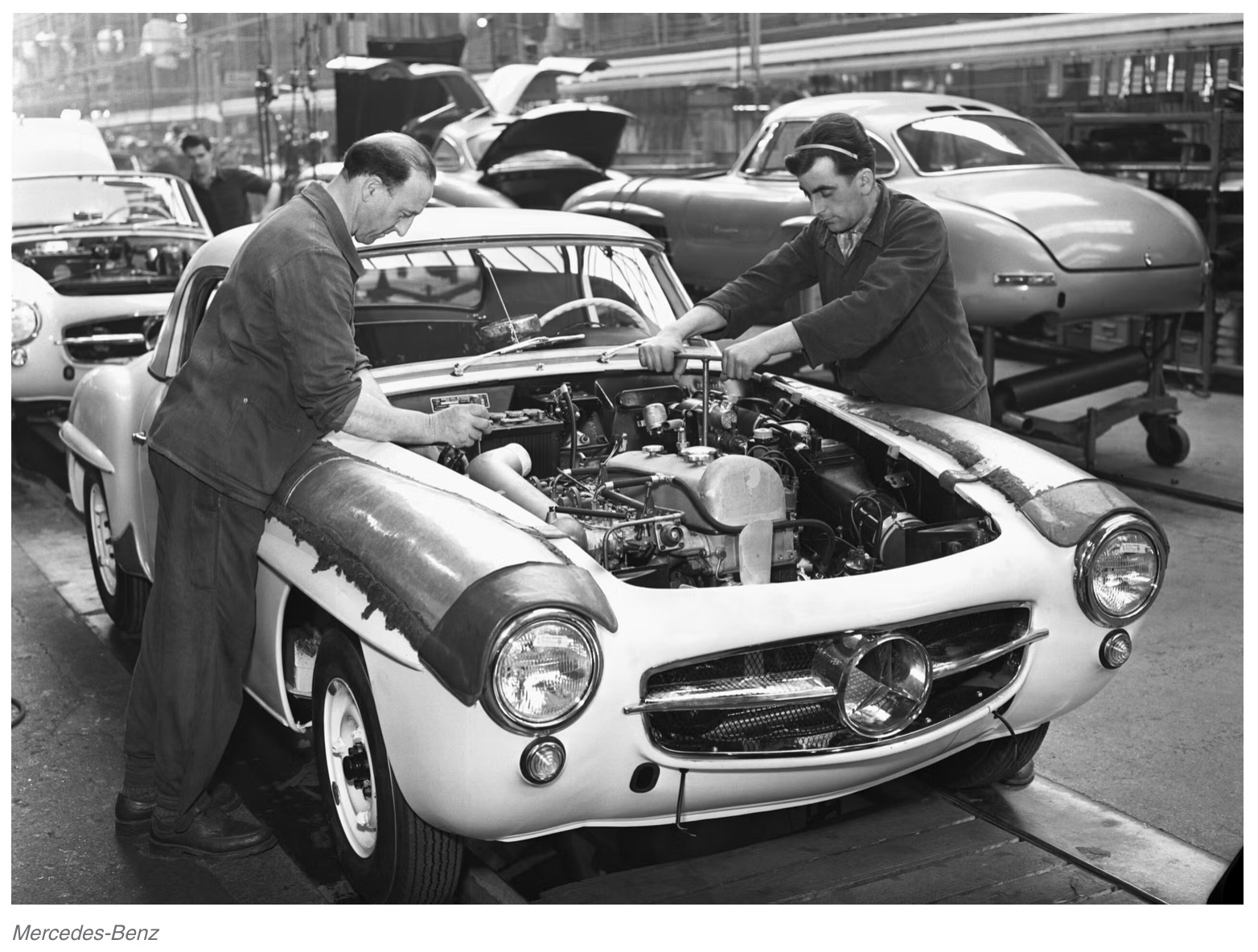

We in 21st-century America are accustomed to thinking of European brands as premium and desirable. That was far from the case at the conclusion of World War II. Much of Europe’s industrial infrastructure lay in ruins; restive populations in both Allied and former Axis countries were still living under conditions so desperate that the United States deemed it necessary to distribute billions in aid across the Continent to prevent communist uprisings. Whereas American automakers entered postwar production at a gallop, satiating pent-up demand with longer, wider, more powerful vehicles, the natural inclination across the pond was to focus on utilitarian transportation: BMW’s most popular vehicle immediately following the war was the Isetta microcar. Mercedes-Benz, best known for massive, commanding vehicles like the 770K, was now focused on demure-looking, practical sedans; its prewar American importer took one look and politely declined to renew business.

But Hoffman knew something about presenting an image of European class, regardless of one’s actual circumstances.

He embarked on an exploratory trip in the summer of 1946. “With the exception of occupation service members, he was likely among the first businessmen to go back to Europe after the war,” Jouret noted. Few automakers were ready to deliver vehicles, but Hoffman nevertheless opened a showroom on New York’s Park Avenue upon his return, with a single vehicle on display. In those early days, he would take to paying above-market price for lightly used European cars, stocking up his inventory, and, in essence, creating the sense that these vehicles were worth something.

Hoffman’s first contract was with Jaguar, and he developed fertile relationships with Alfa Romeo and Lancia, but he soon found his preferred clients: Germans. He was the first to import Volkswagens to the United States—and in fact could have bought the entire company, which was controlled by British occupation forces at the time—and started looking at BMWs as early as 1946.

With the memories of Nazi horrors searingly fresh, many refugees had an aversion to buying from German companies, let alone selling their wares. Indeed, Hoffman Storch suggests it raised eyebrows even within the extended family. Hoffman himself, however, never appeared to take issue with it and, to the contrary, seemed to look upon many of his German counterparts, with whom he shared a common language, as natural partners.

Talking, no doubt, was Hoffman’s greatest talent. “Max was a charming guy,” said Lutz. “Very pleasant and agreeable and interesting,” recalled Ludvigsen, who added that he tended to dominate conversations.

To this day, Americans who work at European automakers will gripe (usually over drinks) that they don’t get enough of a voice in decision-making—that the Germans think they have all the answers. Hoffman, however, was not one to passively sit and listen. When he visited Daimler in the early 1950s, he came with ideas of his own for a small sports car. During his presentation, the automaker’s imposing engineering director, Fritz Nallinger, suggested a sports car could be built on the platform for the 180 sedan. Hoffman simply responded, “Das wird nichts” (that won’t work).

“I didn’t really think before I said it,” he later admitted to Ludvigsen. Hoffman insisted the sedan would be too long and heavy to make the sports car he envisioned but nevertheless was proud of the resulting production car, the 190SL.

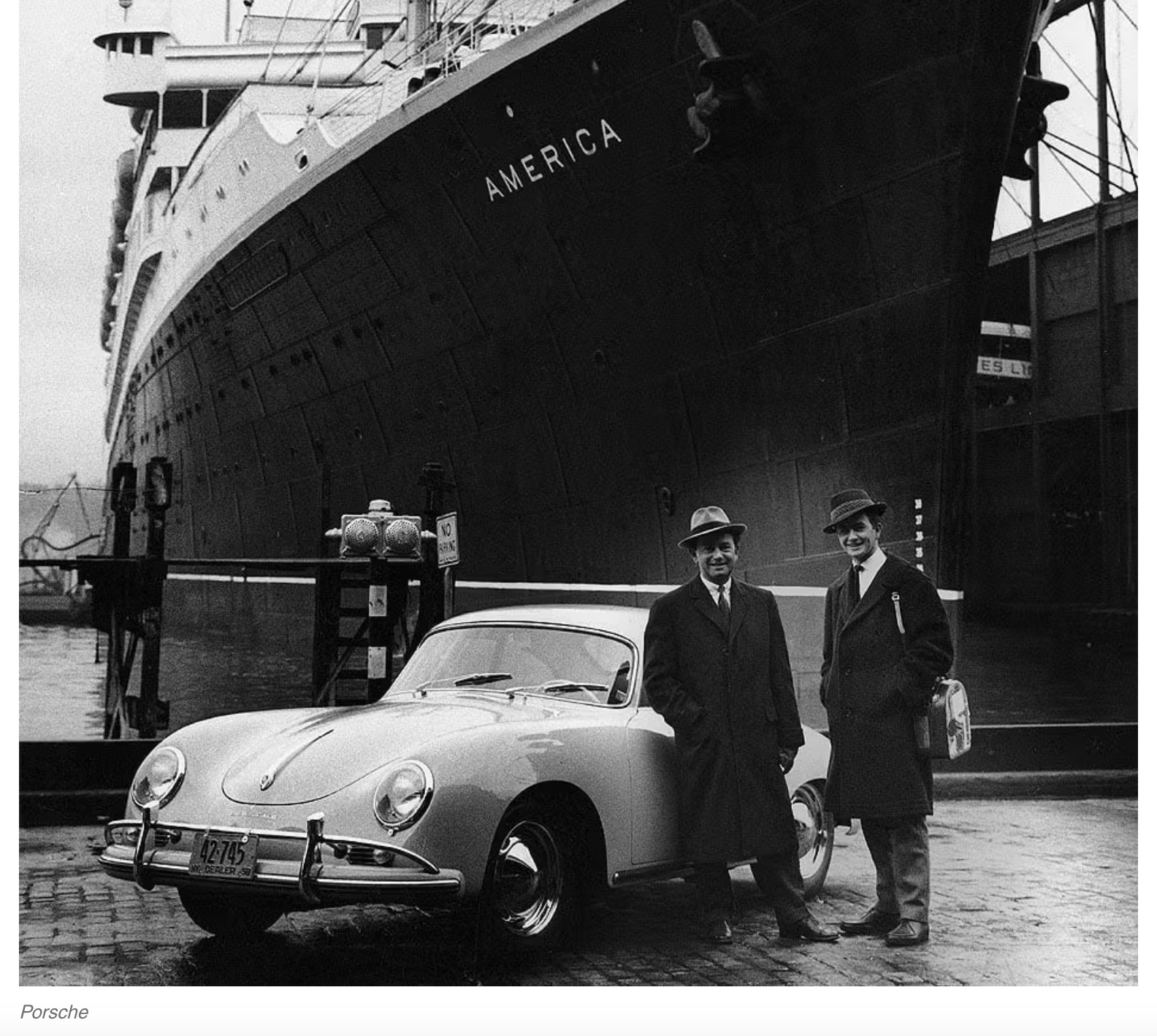

Mercedes, the world’s oldest automaker, apparently was willing to take only so much direction from a New York costume jewelry salesman. Hoffman found more willing collaborators in German upstarts. In 1948, Hoffman learned an old family acquaintance named Ferry Porsche was working on a sports car and was looking to sell, perhaps, a handful a year in the United States.

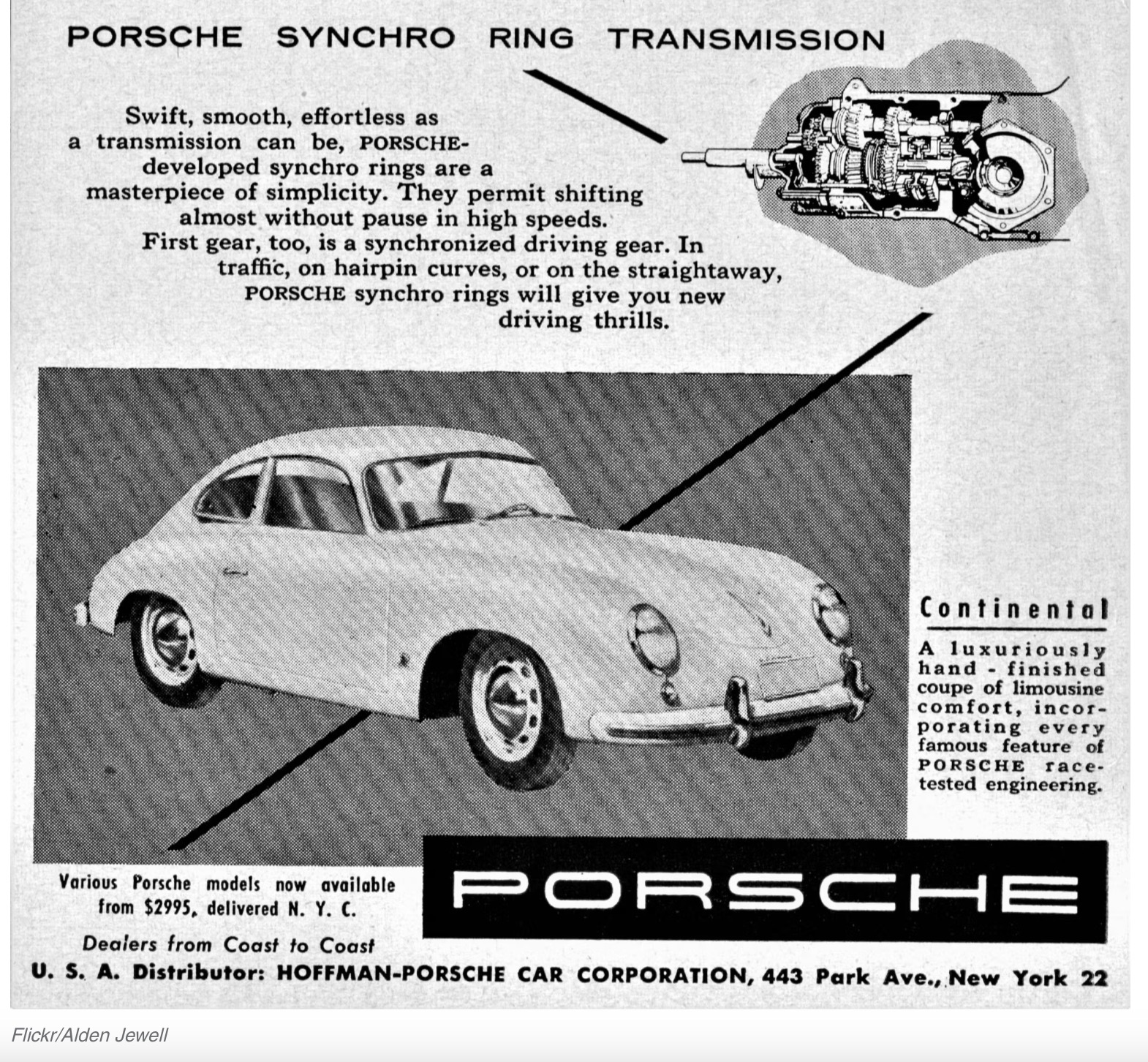

“[Porsche] had no idea of the potential of America,” Ludvigsen said. Hoffman helped them realize and exploit that potential. He not only imported the first 356s to the United States but also helped Porsche secure a lucrative engineering contract with Studebaker and provided a stream of product and marketing advice, culminating in his idea for a stripped-down 356 roadster—the Speedster.

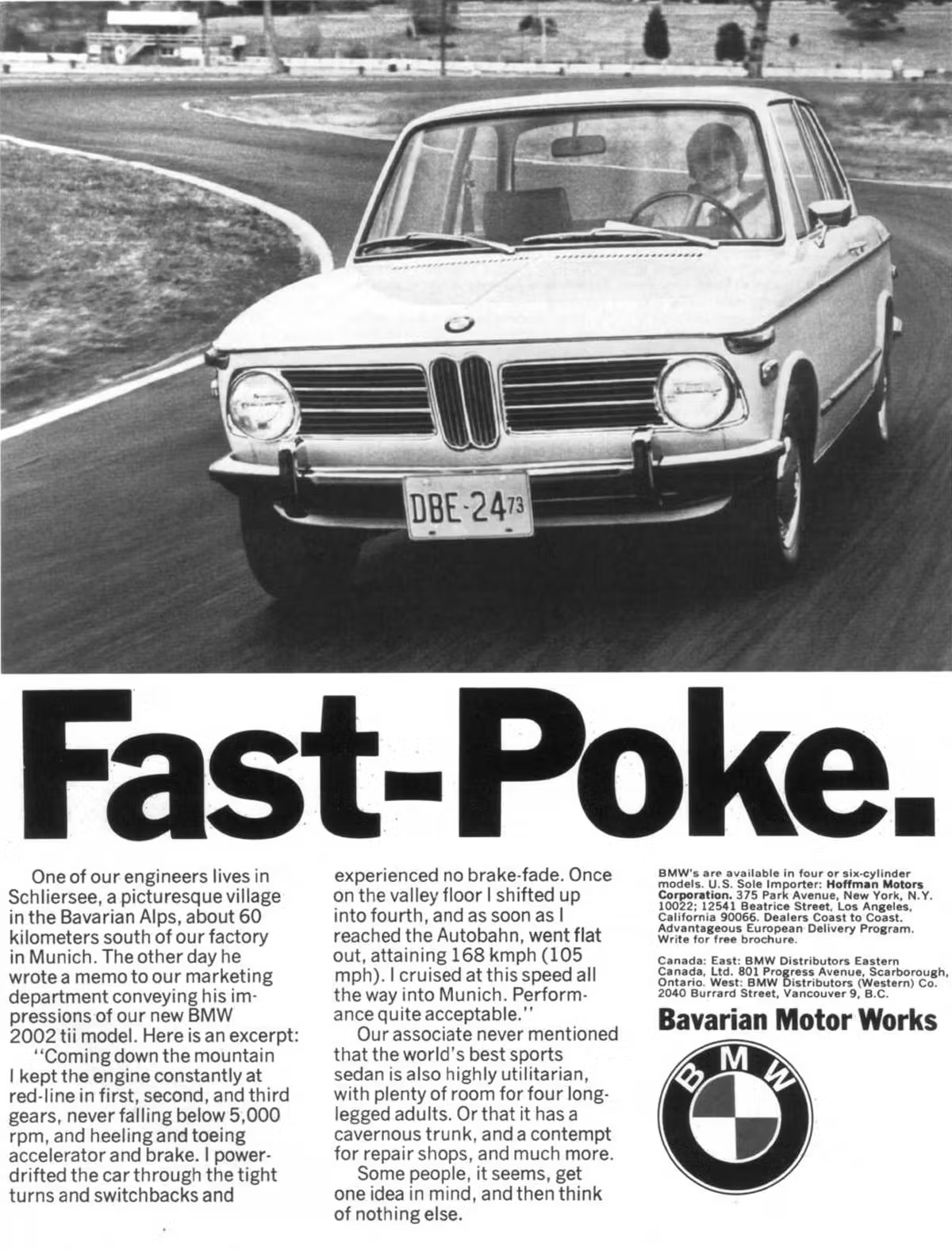

Hoffman found another meaningful partner in BMW. The automaker was for all intents and purposes starting from scratch after the war, its car-making facilities stranded behind the Iron Curtain in East Germany. But it retained a smart, freewheeling team open to input and, by the mid-’50s, was developing a new lineup of sporty cars.

“I think Max and BMW were made for each other,” Ludvigsen said. “They would listen to Max, adapt themselves to some of his ideas.” So when BMW showed him a sports car prototype that he deemed “terrible,” they welcomed his offer to bring in an outside design firm. Shortly thereafter, walking the streets of New York, he ran into Albrecht von Goertz, a youngish German American designer working for Raymond Loewy at Studebaker. Hoffman took the chance encounter as a sign and offered him the opportunity. “I told him if the design was accepted, I would make sure that he was paid—and that if it was not, he would get nothing,” he later told Ludvigsen. The resulting car, the BMW 507, was a commercial failure (and almost sank the company) but is widely considered one of the most beautiful cars of all time. Today, well-heeled collectors pay more than $2 million for concours-level examples.

By the mid-1950s, Hoffman’s fingerprints could be seen all over car culture: The 190SL and its sexier sibling, the 300SL, became icons of the postwar elite, with famous owners ranging from Juan Manuel Fangio to Zsa Zsa Gabor and Juan Perón. Porsches, meanwhile, attracted rebels like Steve McQueen and James Dean. Hoffman never reached that level of fame but certainly lived the high life. He commissioned architect Frank Lloyd Wright to come up with plans for a Manhattan showroom and, not long after, his house in Rye, New York. He bought an office on Broadway, wore expensive suits, and traveled enough that he wound up marrying a flight attendant named Marion.

Nevertheless, his actual business, Hoffman Motor Company, remained a close-to-the-vest affair. He relied heavily on a circle of confidantes that included his sister Risa’s husband, Marcel Melamed. “He was the protector of Hoffman,” noted Ludvigsen. By the late 1950s, this small family company represented more than 20 brands.

Then it all fell apart.

“It Was Just One Huge Corrupt Criminal Enterprise”

In the early 1970s, Bob Lutz was a youngish executive who had recently left his job at General Motors Europe for BMW, working out of Munich. Whenever he’d pass through New York, he would meet Hoffman. And, invariably, he’d get the same proposition.

“If you and I were to become good friends, I can make you very, very rich,” Lutz recalled Hoffman saying. Hoffman then presented a scheme he set up with Lutz’s predecessor, wherein cars were over-invoiced to Hoffman, and in return, a certain percentage of the invoice went back into the Swiss bank account of the sales manager (a form of money laundering). “It was just one huge, corrupt criminal enterprise.”

Lutz, colorful as ever at 93 years old, likes to remind interviewees he is “often wrong, never in doubt.” But he’s not wrong here: Evidence of Hoffman’s self-dealing abounds. He’d negotiate contractual clauses that forced partners to pay him extortionate fees if they decided to separate; he would fail to meet his commitments consistently enough that automakers learned to keep their inventory on the boat until they’d received payment. Hoffman himself regarded this with something of an unconcerned shrug. “I like to get a good deal,” he told Ludvigsen. “If that is difficult, well, perhaps I am.”

Yet it seems even some who worked with him considered him to have crossed the line that separates merely difficult from blatantly unethical. Ludvigsen recalls one Hoffman employee confiding in him, “I just can’t stand behind the way that man does business.”

Hoffman’s take-no-prisoners approach to finances seems to have infected even his familial relationships. Gail Hoffman Storch recalled that at a certain point, her father, John, stopped talking to Max. Although she was too young at the time to be privy to the details, it was likely over money.

“What I remember was that Max started making some money, selling that jewelry. My dad thought he should pay my grandmother, Ida [with whom Max was living at the time]. Max got insulted and moved out with Ida,” she said, adding that both Hoffman men could be “explosive.”

The automakers who did business with Hoffman were, in large part, aware of Hoffman’s excesses and decided it was worth the cost. Until, that is, it wasn’t. By the time Lutz joined BMW in ’72, the company and the auto industry at large were fast moving beyond smooth-talking operators and handshake agreements. As Ludvigsen observed in his Automobile Quarterly profile of Hoffman that same year, the businesses once run by “creators… are run by managers today.” The future was highly structured corporations where accountants closely counted every penny and engineers chased every efficiency.

By the ’70s, Hoffman represented only BMW. “Though he later claimed he’d given up the rest to focus on BMW, the manufacturers had severed their relationships with him one by one over the previous decade… because they deemed Hoffman a customer-service liability, others simply to cut out the middleman,” wrote Jouret in a piece republished by BMW North America. (Various automakers’ official histories, while duly noting Hoffman’s contributions to their success, often can’t help but recount where things went sour, as one might recall a brilliant but abusive parent.)

BMW established its own North American distributorship in 1975, officially ending its relationship with Hoffman and, effectively, putting him out of business. Not that he was left in a lurch. “He wrote contracts with every company that when he was terminated, he got a couple of hundred bucks per car, and that was real money into perpetuity,” said Lutz. Hoffman, now in his 70s, was able to retire with three houses—including the one in Rye, New York, and a vacation home in Germany.

Yet even as his wealth grew, his circle of confidants seems to have contracted. Cut off from much of his family, he spent most of his time traveling among his homes with his wife, Marion, toward whom, multiple sources hint, he could be domineering.

In 1981, while in Bavaria, he fell ill and had to be flown back to the States, where he died at age 76. He reportedly left little in the way of instructions for the distribution of his fortune. He perhaps assumed that his wife, several years his junior, should make the determination. However, Marion herself died two years later, in 1983. Hoffman’s sister, Risa, died the same year at just 65, having suffered effects for years from the difficult conditions she experienced during the war. “She was sick the whole time [in hiding]. She always was her whole life,” said Hoffman Storch.

Hoffman’s fortune thus wound up—after years of legal wrangling—split into two foundations. One, controlled by Marion’s extended family, was set up in Connecticut and continues to give to local causes. The second is run by Hoffman’s former secretary and runs a wildlife sanctuary in upstate New York. They are, according to publicly available tax information, collectively worth many millions today. (We attempted to reach out to both foundations but as of publication had not received a response.)

Neither foundation, as far as we can discern, has a public-facing initiative to preserve its benefactor’s memory, although Myles Kornblatt, author of a 2022 biography of Hoffman, noted that the wildlife sanctuary recently allowed enthusiasts to set up a Hoffman concours on its grounds.

“He Was a Real Innovator”

The globalization of the automotive industry is these days accepted—in some corners reviled—as a banality of the modern age. It’s BMW utility vehicles built in South Carolina, small Chevrolets brought in from South Korea. It’s not being able to get seat heaters in your Porsche due to a shortage in Taiwanese-made semiconductors. This state of affairs is usually credited to economic entropy and national trade policies. Which is reasonable. But it is also a legacy of one unique man, who brought to bear all his experiences, talents, and—yes—his flaws.

“The world is full of brilliant car guys who at the same time were crooks,” said Lutz. There’s little doubt Hoffman could be an unsavory character. Yet so, too, could so many automotive pioneers, from Henry Ford through Volkswagen Group’s Ferdinand Piëch.

Unlike those men, Hoffman left behind no children and/or active corporations with direct interest in exalting his genius. There can be no mistaking the fact that he was, in fact, a genius, not to mention a true-blue car enthusiast.

“He was a real innovator, obviously, who brought a lot of things,” noted Hoffman Storch. “I’m not saying they wouldn’t have happened, but maybe not as fast.” She added that, although her father, John, never had a rapprochement with his glamorous cousin, he always felt connected. “I think my dad was very proud of what Max accomplished… but would never tell him that.”

To presume that he was simply the right man at the right time—that the globalization of the auto industry would have unfolded without him—is to ignore his significant contributions to the automotive pantheon, not to mention the fact that as a war-scarred refugee, he was in many ways the wrong man at precisely the wrong time.

This story could not have happened without the generous assistance of several people: Relative Gail Hoffman Storch and the Institute for Jewish History in Austria illuminated details of Hoffman’s early life. Veteran journalist Karl Ludvigsen sharedHoffman interview notes dating back to the 1970s. Retired executive Bob Lutz and automotive historian Jackie Jouret, meanwhile, helped us better understand Hoffman’s crucial years working with BMW. Thanks to you all.

Report by David Zenlea for hagerty.com

![Is this the greatest racing film oat?

In “Ford v Ferrari”, one of the most important

moments comes when Ken Miles takes the GT40 out for a test run after it’s fitted with its massive new 7.0 litre V8. The scene captures a turning point in Ford’s effort to challenge Ferrari at Le Mans, with Miles pushing the prototype hard at Ford’s Dearborn test facility.

With his trademark intensity, Miles immediately feels how the car responds to the raw force of the 427 cubic inch engine. The sound, speed, and feedback through the steering wheel signal that the GT40 is finally becoming something special.

The moment isn’t just cinematic drama, it reflects real history. The big block 427 gave Ford the power it needed to fight Ferrari, and Miles’s deep mechanical understanding played a key role in shaping the car’s behavior on track.

Despite Ford pouring more than $25 million into the program, it was experiences like this, Miles sensing every detail from behind the wheel, that turned early prototypes into Le Mans winning legends.

( Media via “Ford v Ferrari” [2019] )](https://collectorscarworld.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)