JAN MERSCH is a psychologist and a climbing and ski guide. His coaching concept combines both of these competencies. He has scaled some of this world’s tallest peaks, so he knows all about challenges and how to define failure and success.

He also knows what kinds of experiences count as an adventure.

Mountains have always been a source of fascination for us. They compel us to climb them, to reach new heights, to achieve something through effort, to discover ourselves in the challenge. Should we all be climbing mountains more often?

I’m a bit torn on that one. I’m not the kind of person who believes we’d have a better society if everyone climbed a mountain more often. Though I do believe that we have lost touch with nature, and that hiking and mountain climbing in particular can open up a lot of possibilities for us that can go from a more spiritual engagement with nature to truly extreme and primal life-and-death situations. But I also think that you can lead a fulfilled and happy life without ever going to the mountains. Some people find happiness in a chess club, in a local culture association or wherever. I personally don’t understand how people can be happy without mountains or nature, but I know that they can. I, however, could not.

You’re an elite mountain climber, later you studied psychology, and now you work as a mountain guide. Why psychology? Why this combination?

I think that the intense life that I have led has given me an enormous treasure of experiences, insights and knowledge that are constantly resonating in the here and now. This has allowed me to develop a great sense of serenity and calm: I can truly relax and look forward to what comes next. And often, those are the little things. As for my career path: I became a mountain guide while I was still in school, though it was never my intention to do that as a profession, to work with people all my life in what is essentially a manual job. So I started to study physics – but I quickly realized that it wasn’t the right thing for me. I then switched to psychology. Even before I finished my studies, I knew that I didn’t want to help people within the rigid confines of a practice, but that I wanted to assist people in dealing with a specific topic, who wanted to develop and grow. And so one thing led to the other, and that’s how I ended up where I am today.

Do people always need something that challenges them? The next big adventure?

No, I don’t think so. At least, this isn’t true for everyone. I do believe that there are people who can be happy without challenges or personal growth. On the other hand, there are people who are constantly looking for a new challenge, but who remain happy in their eternal pursuit, who perhaps are trying to compensate for something, but fail to achieve any kind of satisfaction.

But don’t we always stand to gain from embarking on a new adventure?

At this point it is necessary to make a small excursion into the field of philosophy and to first of all be clear about what we mean by “adventure”. Thinking about my own personal experience, I have to think back to my mountaineering past at the end of the nineties and the beginning of the new millennium. That was extreme alpinism, a level that only a handful of people in the world had reached. At that time, we were climbing the difficult seven-thousanders in the Karakoram – the Champions League of mountaineering, if you will. There were only two or three people from Slovenia and two or three from France who were doing what I was doing. Those were adventures in the wilderness where you were actually constantly wishing for it to be over. These were truly life-or-death adventures with lots of decisions and lots of extreme situations.

So is danger a prerequisite for adventure?

That’s how I defined it for myself. An adventure is a situation you wish was over. Today, as a mountain guide, I define adventure quite differently for my guests. The guests should have the feeling that they are experiencing an adventure. As a mountain guide, however, I am concerned with their safety, so our excursion absolutely cannot be an adventure according to my own definition of the word. I try to give people a certain level of calculable risk, where they can experience what to them feels like an adventure with their own level of skill. Adventures are a very personal experience that takes place differently in the mind of each individual. For someone who hardly ever goes out into nature, the adventure begins when they leave the paved road in the alpine foothills and hike out into the forest a bit. That’s not an adventure for the experienced mountaineer, but it is for the inexperienced city dweller.

What you’re saying is, the adventure begins when you leave your comfort zone?

That’s where growth begins. The moment I leave my comfort zone, I grow. I start to learn. The fine line you have to tread is not to become overwhelmed, not to cross the line where panic sets in. So the trick is to hit that fine dividing line. Then you grow. Getting back to extreme mountaineering: that’s exactly what we were so good at. In the end, you always fail when you don’t hit that perfect balance between challenge and skill. But, again, I do believe that there are people who can live very happily without ever leaving their comfort zone and without this growth. For these people, it’s enough to sit in the armchair and watch a movie about climbing. Maybe at night they dream of an adventure climbing a mountain, and that’s it.

So that means the people who come to you are the sort that want to leave their comfort zone?

That’s right. I did a special behavioral therapy diploma, and I work with people’s personal biographies and emotions. That means I look closely at where they come from and what has made them who they are today. To get this information, I conduct a classic therapeutic interview in my practice, sometimes with the use of a flipchart or questionnaires. If someone says they want to go out into nature, I can have these conversations outdoors, even while mountain climbing. The exact process can be quite different depending on the person’s abilities. Sometimes we start at the parking lot, walk a bit, sit on a bench, walk a bit more. Other times we climb first, then take a break. Something like that. Everything gets the space and time it needs. Do it like this way for two or three days, and the effect is a different one than saying, “Fine, goodbye, see you next week!” after a ninety-minute session. Obviously, climbing a mountain together involves a completely different level of trust. People who trust you will open up much more deeply. And this trust is formed during the adventure. In a way, that happens all by itself, because you really have to rely on the other person. For me, climbing a mountain together is not a method, but a space that I create where thoughts can take a different direction.

So it’s about staying in motion, in both the physical and mental sense?

Exactly. And when you’re standing there together on a mountain peak, that opens you up to things. Or when you walk through the forest and you take in the sights and smells of nature. That changes you. Same thing with climbing, when you have to be fully focused and balanced. Everything else just fades into the background. Or skiing, with its rhythm and its focus on anticipating the next turn, on finding the line you are going to follow, until you enter into that state of flow. That all supports the internal psychological processes that we want to set in motion.

Does that also you help in dealing with failure?

We already touched on this briefly before. On the one hand, when I fail at something, I have to be clear about the fact that I probably didn’t exactly hit that fine line between leaving my comfort zone and the limits of my abilities. At the same time – and I’d like to go back to mountaineering here, if I may – external factors play a role too, of course. Alpinists often don’t reach a certain goal simply because the weather was against them. Only when the conditions are perfect, but you still don’t reach your goal, can we blame the failure on a lack of ability, or because you overdid it, or because you chose a challenge that was too big, or because you underestimated the risk or the danger of dying. This is a very fine line. Because this is where growth takes place. And without crossing this limit at least a little bit every now and then, you won’t develop your skills any further. You just shouldn’t die in the process.

In the same way that you set goals for yourself as a mountaineer, do you also have a set of goals or ideals for life?

The goal I have set for myself is to feel good about myself and my needs. I strongly follow Klaus Grawe’s personality model with pleasure-seeking and pain-avoidance, orientation and control, attachment, self-enhancement and self-esteem; in other words, all those factors that are important for mental health and resilience. That is my background, and that is my view of the human psyche that I have developed for myself. It also includes being aware of one’s own weaknesses, recognizing one’s own imperfections and always using the opportunities to start over, to correct, to reflect. I think these are the things that make people happy.

Speaking of which, how would do define happiness?

I feel very fortunate to have a job that makes me happy. I find my work extremely exhausting while I’m doing it, it truly drains me energetically speaking. When I come home on Friday evening, I’m finished. I don’t need to do anything else for the weekend. Of course, there are other weeks that are less intense. But I never have the feeling that my fees are a compensation for some kind of pain. I’m being paid for doing something that I love to do, even if I always think it’s not enough, that I could do more. The second pillar of my happiness is my family and my social life. I feel very secure here. I have a very good home environment and a good foundation to stand on. I am also fortunate to be able to go mountaineering, to have access to nature, and that I have my own private time. Because being a mountain guide, leading groups through the mountains, is not my own time. That time is not about me, but about my clients.

And what is luxury for you?

Being able to live your life the way you want, perhaps, and to have a job that makes you happy – that feels like luxury to me, because it leads to a kind of inner peace. Or when I have time to go skiing in good snow. Of course I also enjoy staying at a good hotel where I spend a lot of money on good food and good wine. That’s also luxury. Material luxury. But that’s not so important. I also think it’s luxury to be able to go to the market and buy fresh vegetables or good cheese. That feels like luxury to me. Or to take the time to prepare a meal, to cook your food for the joy of it and not just because you have to eat.

When the moment in itself is precious . . .

To consciously experience the moment in everyday life – not just ordering a pizza but taking your time to enjoy the experience of cooking a meal. In other words, to be aware of the things you are doing. To just be in the here and now, to be able to go skiing in perfect conditions or to spend time together climbing with a close friend. And I don’t want or need to share this moment with people who aren’t here, just like I’m really not interested in sharing their moments when I’m not there with them. I totally refuse to use social media because that has nothing to do with the real moment and with my own happiness. It’s a total waste of time.

To live in the moment, no matter if it’s a great adventure or a minor everyday task?

Exactly. Speaking of adventure, I do have this yearning to return to the world of extreme mountaineering. I was at a Champions League level around the turn of the millennium. And while I don’t need to go back to that, I do feel the need to go back to doing something more extreme. That’s what’s so great about mountain climbing: the adventure is not defined by what I see from the outside, but by what I feel inside, by my possibilities, my limits, my abilities. That means that even if I’m twenty or thirty years older today, I can still feel the same intense sense of adventure. I still carry all that within me, and I would like to answer that call as soon as my family circumstances with children, school and other issues are less pressing. That also requires the right amount of preparation. It takes me a year and a half of planning before I can travel to Pakistan to tackle a seven-thousander.

Do you feel like you’re missing something?

I wouldn’t say that I’m missing something. At the moment, there are just so many little things that take up space in my life. I still look for the adventure in these little things, and I find it there too. But bigger things like mountaineering expeditions, where I know what that feels like and what it should feel like, where I go away for months at a time and where really nothing else matters, because it’s all about surviving and coming home again, I just don’t have time for that right now. But the longing? That’s still there inside of me.

JAN MERSCH, born in 1971, began climbing mountains already in his childhood. Since 1985 he has been on mountaineering expeditions throughout the Alps, since 1990 also in Asia and the U.S. From 1999 to 2005 Mersch was the national trainer for the German Alpine Club’s expedition team. Today, as a certified psychologist and mountain guide, he leads people through the mountains and their inner issues with his People and Mountains concept menschundberge.com. Mersch lives with his family in the Chiemgau region of southern Bavaria.

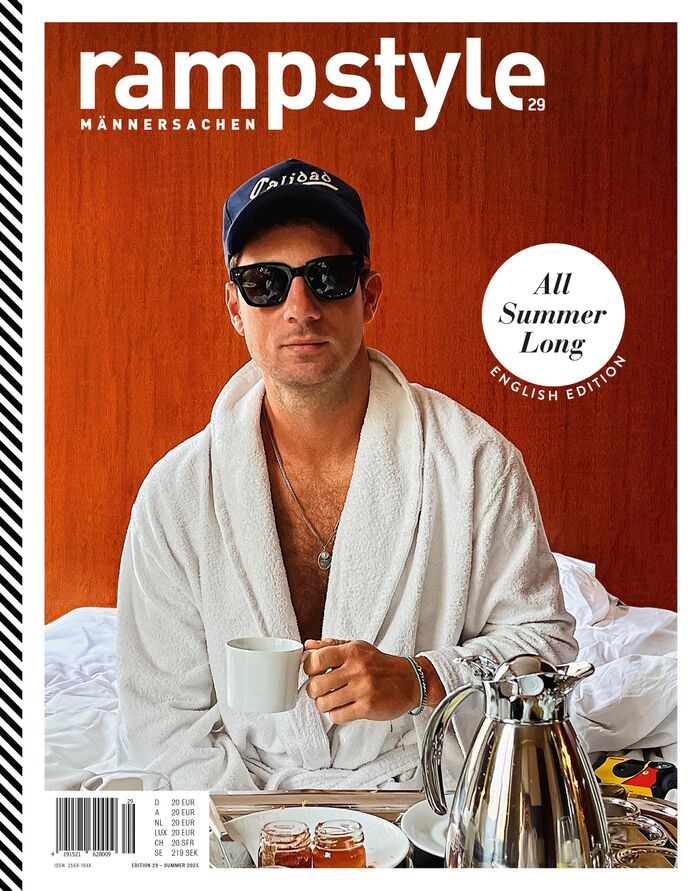

rampstyle #29 All Summer Long

Barcelona in summer. With Alvaro Soler – and a Porsche 911 SC. An approach to the phenomenon and the person Yves Saint Laurent. We spoke with Udo Kier in Palm Springs, and Luc Donckerwolke in his garage. And then there’s the cover – and the associated story of House of Spoils. Find out more

Interview by Michael Köckritz for ramp