The 24 Hours of Le Mans celebrated its hundredth anniversary this year. Our author was there. For the start, he wore his Jochen Rindt sunglasses – to hide his emotions.

I.

Le Mans is located in the region of Pays de la Loire in northwestern France, 184 kilometers southwest of Paris. The village of Mulsanne, situated at the end of the straight of the same name, is home to 5,295 people called Mulsannais. Across from the Church of Sainte Madeleine, a very old man with white stubble is sitting on a plastic folding chair in front of his house. He was a child when the German prisoners of war were brought here to the nearby camp. And it was about the time of his first love when he saw black smoke rising into the sky at 6:26 p.m. on June 11, 1955. Pierre Levegh (a Frenchman of all people!) had crashed into the crowd at the start-and-finish straight in his Mercedes 300 SLR after colliding with the Austin-Healey driven by British racer Lance Macklin. The car exploded, killing Levegh and eighty-three (!) spectators. The accident was triggered by fellow Brit Mike Hawthorne, who had suddenly braked in front of Macklin to turn into the pit lane. The old Mulsannais says in a weak voice: “The fire and all the dead, it was like the war all over again.”

II.

The race is not as dangerous as it used to be. The last fatality ten years ago was Danish racing driver Allan Simonsen, thirty-four years old. Accelerating out of the Tertre Rouge, Simonsen lost control of his Aston Martin Vantage and hit the crash barriers, the force of the impact ripping out the passenger door. Otherwise, the car did not look badly damaged. There was a tree directly behind the barrier that prevented it from deforming. Simonsen was responsive after the accident, but died a short time later from cardiac arrest. The Tertre Rouge, a right-hand corner, was modified accordingly. The cars have become even safer. And the six-kilometer-long Mulsanne Straight (French: Ligne Droite des Hunaudières), where the cars had previously zoomed along at 400 km/h, was defused by two chicanes back in 1990. So the words of Viennese motorsport journalist Helmut Zwickl, written on the occasion of the death of Porsche driver Jo Gartner on June 1, 1986, as part of the best story about Le Mans of all time, no longer really apply: “Death at Le Mans comes slowly. It has twenty-four hours at its disposal. Death at Le Mans is called cancer. Material cancer. First a few metastases that nobody notices. They grow and spread deep down in the material, nourished by the vibrations and centrifugal forces. You’re lost long before you know it, and it’s a good thing that you don’t.”

III.

The Friday before the race. A large room at the Le Mans football stadium, just a stone’s throw from the Mulsanne Straight. Official press conference. The Japanese Piëch steps up to the podium: Akio Toyoda, mid-sixties, small and mercurial, short-sleeved shirt, grandson of Toyota founder Kiichiro Toyoda. (And because someone out there is bound to be asking the perennial question: Why are the cars called Toyota and not Toyoda? The Toyodas wanted to keep their work and their private lives separate, so they named the company after the city in which it is based: Toyota.) The former CEO and current chairman of the board of the world’s largest car manufacturer congratulates the organizers on the hundredth anniversary. He has come to Le Mans to celebrate Toyota’s sixth victory in a row. Though he doesn’t say so with words, because Japanese humility forbids this even at the peak of success. And he can probably read what is written on the faces of most of those present: “That’s enough – time for your party to end.”

IV.

Le Mans had basically been half-dead. We have the gentlemen responsible for the diesel scandal to thank for that. At the end of the 2016 season, VW subsidiary Audi withdrew from the race, and a year later its sister company Porsche announced its exit as well. With fines running into the billions, Volkswagen Group could no longer justify its sinfully expensive motorsport projects. In 2018 Toyota stood alone – meaning: they still had a few minor opponents in their class, mainly privateers without a chance of winning, teams they could easily drive circles around. And through no fault of their own, the Japanese had to listen to the complaint that their victories were nothing more than innocuous strolls in the park. True enough. But what should they have done? Turn tail like the Germans – even though they hadn’t hurt themselves with falsified exhaust values? They would have been stupid to do that.

V.

Now, just in time for the hundredth anniversary, the grandiose rebirth of the most famous of all car races! In the top class, a starting field the likes of which has not been seen in ages – Porsche, Ferrari, Peugeot and Cadillac are back. Glickenhaus, the legendary team of the former American film producer and financier James Glickenhaus, is sending two cars into the race. The line-up in the top league is completed by a car from the Vanwall Racing Team based in Greding, Bavaria. The owner is Romanian-German ex-Formula 1 team principal Colin Kolles, one of the most bizarre figures in racing. In 2005 Kolles, who is a qualified dentist, performed a root canal on his driver Tiago Monteiro (Team Jordan) in the paddock before the Turkish Grand Prix. Monteiro had been in so much pain that it jeopardized his participation in the race.

VI.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans are part of the FIA World Endurance Championship (WEC). The race is contested in three classes: Hypercar (closed-cockpit sports prototype race cars or modified road-going sports cars, max. 680 hp, optionally with or without hybrid powertrain), LMP2 (Le Mans Prototype 2, closed-cockpit sports prototype race cars, naturally aspirated V8 engine, max. 542 hp), and LMGTE Am (Le Mans Grand Touring Endurance Amateur, production-based sports cars, max. 5.5-liter naturally aspirated or 4.0-liter turbo). A total of sixty-one cars – finally, all hell is breaking loose again at Le Mans!

VII.

Four hundred thousand spectators! The whole population of Iceland, with that of a minor South Pacific nation to top it off. Le Mans is more than just a car race, it’s a public festival. The action both on and off the 13.6-kilometer track is unbelievable. A Ferris wheel. Food stalls. Irish pubs. Souvenir stands. Showrooms from the participating racing teams set up overnight. Sotheby’s has erected a huge tent to auction off old Le Mans race cars. A 1955 Ferrari 121 LM goes under the hammer for €5.7 million. Yet no one is willing to put up the minimum bid of €5.5 million for the legendary blue-and-white Rothmans Porsche 962 driven to third place by Hans-Joachim Stuck and Derek Bell in 1985. An outrage!

VIII.

Alpine, the French contender, has built the most amazing viewing platform imaginable for its guests on the roof of a glass hospitality building. I look down to the exit of the pit lane. On the left, the start-and-finish straight. On the right, the track up to the Dunlop Chicane. In the middle, a square bar where the champagne is chilled. The brand, a member of Groupe Renault, will be competing in the LMP2 class this year. A hypercar is ready to start in 2024: the Alpine A424. Mecachrome 3.4-liter turbocharged engine with standardized hybrid powertrain unit and 671 hp. The car was presented after the press conference here at Le Mans. Sophia Flörsch – who is currently competing in Formula 3 and has been accepted into the official junior squad of the Alpine F1 racing team – was spotted excitedly taking photos with her smartphone. Whenever you see her, you can’t help but be reminded of her horror crash in Macau five years ago. It’s a miracle she’s still with us. Long live Sophia!

IX.

When was the last time you saw the hapless Ferrari F1 driver Charles Leclerc looking so radiant? He’s walking through the paddock, posing for selfies every five meters. We ask him, “Who’s going to win today?” Without a second of hesitation: “We are.” – “Why so confident?” – “Because we have double pole position and we’ve won the 24 Hours of Nürburgring – with a completely new car, the 296.” – “Will the new 499P go the distance?” – “Yes, we’re going to win.” – “When are you going to win a Formula 1 race again and redeem us from these tedious Verstappen pageants?” The likeable Monégasque smiles and shrugs, “We’ll see.”

X.

Saturday, 3:59 p.m. The Alpine roof is packed with experts, semi-experts, none experts, real fans, absolute poseurs and high-class alcoholics who, accompanied by fat Havana cigars, are slowly gliding out into the open sea of drunkenness and who, before nightfall, will no longer know their names, how they got here or where all that noise is coming from.

XI.

4:00 p.m. sharp. The pack is off and running. What a fiery, flaming orchestra of displacement volume and engine speed! The author of these lines is in a near catatonic state and has to keep his Jochen Rindt sunglasses on – although rain clouds are already in sight – because he needs to cover his eyes, which are moist with emotion. Only his quivering lips could betray his state of mind. But he certainly doesn’t want to hide his stormy thoughts: Formula 1 can pack it in against this show here! Shame on you, F1! Your engines are quieter than Formula 2 and Formula 3! Even the Porsche Carreras running in the supporting program are louder! Embarrassing! Top class of motorsport? Ha, don’t make me laugh! The true top class is here, now this is motor racing!

XII.

What a race! At one point, Ferrari is in the lead. Then Toyota. Then Cadillac. Then Porsche. Then Peugeot. This much is certain: Toyota’s strolls in the park are a thing of the past. Soon it starts to rain, the track becomes an aquaplaning trap. Veteran drivers suddenly look like helpless learners, spinning off the track one after the other and crashing into the barriers. Granted: Because nobody gets hurt, it’s actually quite an entertaining show.

XIII.

I find myself engaged in conversation with an actual A1 expert at the parapet of the Alpine roof. Swiss, mustache, glasses, sunburn. With his wealth of knowledge, he embarrasses me to the bone. The black and yellow Cadillac thunders up to the Dunlop Chicane. The A1 expert: “Looks cool, but it’s nothing compared to the Lancia Stratos. We need a car like that here.” – “With respect,” I reply, still feeling like I might have the upper hand, “the Stratos was a rally car.” – “Well, yes, but not only,” the A1 expert winks slyly and adds, “Two Group 5 Stratos were built for circuit races. They competed at Le Mans in 1976 and 1977. You didn’t know that?” – “No, is that a bad thing?” – “No, no, not at all.” (Of course it’s a bad thing, I would have liked to have slapped myself for my own ignorance.) The A1 expert continues: “By the way, it was an all-women’s team in 1976: Christine Dacremont and Lella Lombardi.” – “How do you know all this?” I ask with suppressed anger. “Is that something special? I thought I was among the informed here. You’re lucky the champagne is free, because it would have been on you. Now go bring us two glasses.” I comply with the request, and when I hand the glass to the A1 expert, he asks: “What do you do for a living, if I may ask?” – “Um, veterinarian, small animals only.” Should I, as ignorant as I have proven myself to be, have said that I was there representing a car magazine called ramp?

XIV.

Night. Not much going on up here anymore. Across the way, the big grandstands are mostly empty as well. They’ve all gone to the pubs or to sleep in their hotels, tents or mobile homes. Only at daybreak will they return, one by one. I want to hang on. I think of Pierre Levegh, the unlucky driver involved in the 1955 accident. Three years before the disaster, he single-handedly drove his Talbot-Lago for twenty-two hours straight before bowing out of the race due to engine failure. To this day, it is the greatest driving achievement in Le Mans history. During the pit stops, the privateer Levegh simply stayed in the car, refusing to let his co-driver René Marchand take over. He was concerned that the less experienced driver wouldn’t know how to properly treat the already battered engine. That would be unthinkable today – it would result in an immediate disqualification. My conclusion: If Levegh could drive for twenty-two hours without rest, I should be able to stay awake for twenty-four hours to watch the race.

XV.

3:30 a.m. I stroll through the paddock. It was here, right at the front entrance behind the pits, where Audi had parked its motorhome twenty-one years ago. It was the middle of the night back then, too. I was allowed in to see Frank Biela, who had handed over his R8 to teammate Emanuele Pirro just half an hour before. They were clearly on their way to victory. Audi’s dominance at the time was overwhelming. Biela was seated on his bed in his fireproof undergarments, leaning back against the wall. Actually, he should have been getting some rest. But how could he, with the noise of the engines penetrating through every crack with a dull, booming sound? “Can you sleep here?” I asked the man, who a few years earlier, at a Super Tourenwagen Cup race on Berlin’s AVUS circuit in 1995, had crashed into the driver’s side door of a rival, unable to avoid the already accident-stranded car in time. British driver Kieth O’dor had no chance of survival. “Sleep is out of the question. But it’s not just the noise. Earlier, I had my eyes closed for a few minutes. But then my feet started moving automatically, as if I were pressing the pedals in a race car. That woke me up again.” – “If you can’t get any sleep, how do you start your next turn behind the wheel at least halfway rested?” – “I don’t really need to rest. When I get back in the car, I’m pumped full of adrenaline again. That’s enough.” – “The sound out there is that of the other drivers racing through the darkness at over 300 km/h. Kind of eerie. Almost frightening, isn’t it?” – “I can’t think like that.” – “So how do you think?” – “Everything will be fine, like last year. We won last year.” – “Aren’t you worried that something could go wrong with your car at full throttle and in top gear? One of your team members was killed in an R8 last year: Michele Alboreto, during testing at the Lausitzring, a tire puncture.” – “It was a big shock for all of us. But it’s true: on the long straights you do sometimes think stupid things.” – “What kind of things?” – “Stupid things, like I said.” – “That it could also happen to you?” – “Of course.” It never happened to Frank Biela. He won the race. And not only that one. He’s a five-time champion at the Circuit de la Sarthe and, together with Derek Bell and Emanuele Pirro, the third most successful driver at Le Mans (behind Tom Kristensen and Jacky Ickx).

XVI.

At 4:30 a.m., I’m overcome by fatigue after all. I lie down on a couch opposite the (closed) champagne bar and doze off. No one else is there.

XVII.

Up to the halfway point of the race, the competitors in the Hypercar class were running pretty much head-to-head. Then Porsche fell back with its 963. There goes the twentieth overall victory to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of the brand. It comes down to a duel between Toyota and Ferrari. Of the four hundred thousand spectators, three hundred and ninety-nine thousand are rooting for Ferrari. When the Italian team takes the lead, the crowd erupts in cheers. When Toyota takes the lead, there is silence. Strange, isn’t Toyota a car for the masses? And because things are so exciting in the top class, the equally thrilling competition in the LMP2 category is somewhat overshadowed. The Polish privateer team Inter Europol is in the lead and looks set to win. Imagine a twenty-four-year-old behind the wheel with a swollen foot and lips clenched in pain. During the driver change, a Corvette ran over his foot in the pit lane. But wait a minute . . . Inter Europol? Can you think of a sillier name for a racing team? Do they have handcuffs, live ammunition and arrest warrants on board?

XVIII.

Almost too good to be true: 1973, exactly fifty years ago, was the last time Ferrari competed in the top class in factory racing. And here they are, sending their cars into the hundredth edition of the race with the symbolic starting numbers 50 and 51. And go on to win that race, too! Forget Hollywood, totally overrated (as actor Michael Fassbender proved when he crashed his Porsche 911 and had to pack up early.) A minor cosmetic flaw: the winning car was number 51. The winning trio: Antonio Giovinazzi/Alessandro Pier Guidi/James Calado. The last time the guys from Maranello triumphed in the top class was in 1965, with Jochen Rindt/Masten Gregory/Ed Hugus in a Ferrari 250 LM. Are some of you scratching your head now? Who the . . . ? Ed Hugus? Yes, sports fans, this certain Ed Hugus was the third man that nobody seems to remember. You won’t find his name in the official results list, and there is no champion photo of the three of them together. Why is that? As the story goes, Masten Gregory, who was extremely nearsighted, came into the pits at four o’clock in the morning. He couldn’t continue because he had gotten too much smoke in his eyes. (As every year, there were hundreds of barbecues burning around the track.) Next up would actually have been Jochen Rindt. Unfortunately, nobody knew where he was. They looked for him everywhere – with no luck. Rindt had disappeared off the face of the earth. But Ed Hugus was there, and so he put on Masten Gregory’s helmet and finished his laps – Ed Hugus as Masten Gregory, so to speak. If that had come out, they could have forgotten about winning, so they kind of just let Ed Hugus slip under the radar. It’s a rumor, but a glorious one that we’re happy to pass along. Before we forget, and for the sake of completeness, Toyota finished second today, about ninety seconds behind Ferrari. Ninety seconds after twenty-four hours – that’s a blink of an eye. Third place goes to Cadillac.

XIX.

Monday. The quiet after the storm. In the pedestrian zone of Le Mans, the handprints of past victors are set into the ground on plaques. If you were one of today’s young heroes – Giovinazzi, Guidi or Calado, whose names are sure to be added to this tourist attraction here soon enough – wouldn’t you want to have the words “In Memoriam Ed Hugus – Le Mans Winner 1965” added to your plaque? The uncredited third man behind the wheel died in 2006 – and not just anywhere, but in Pebble Beach, as befits his status.

- Preview: Le Mans 2024 – with BMW and Lamborghini entering in the Hypercar class!

XXI.

The Jochen Rindt sunglasses? Pure coincidence!

Text: Kurt Molzer

Photos: Marko Knab · ramp.pictures

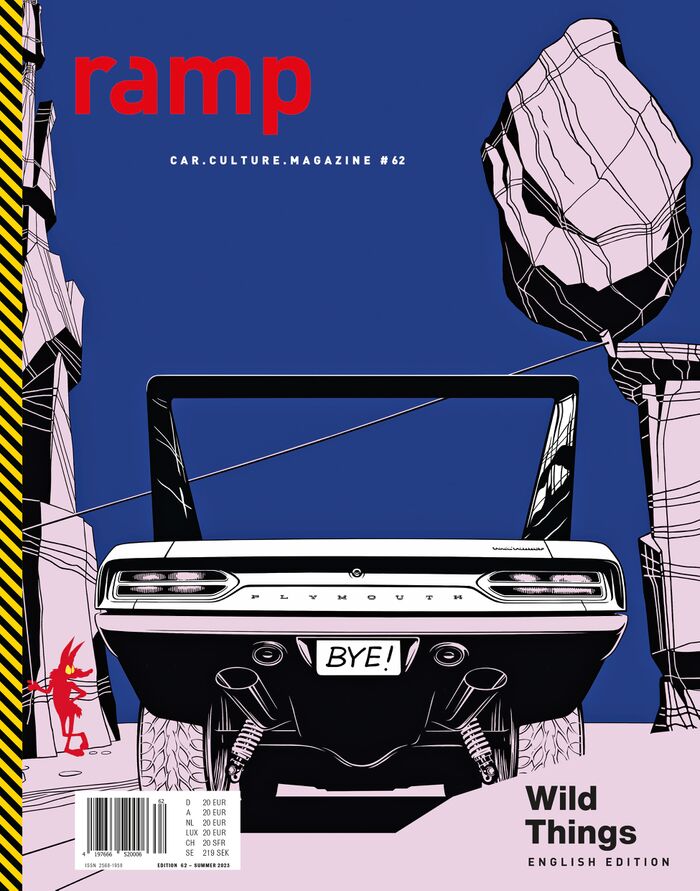

ramp #62 Wild Things

Just heading along, the journey itself a wonderfully blank page that presents itself to us with a cheerful unpredictability, as an inspired playing field for trial and error, for curiosity and spontaneity, unexpected surprises and flights of fancy. Wild and untamed. Just like life itself. Find out more