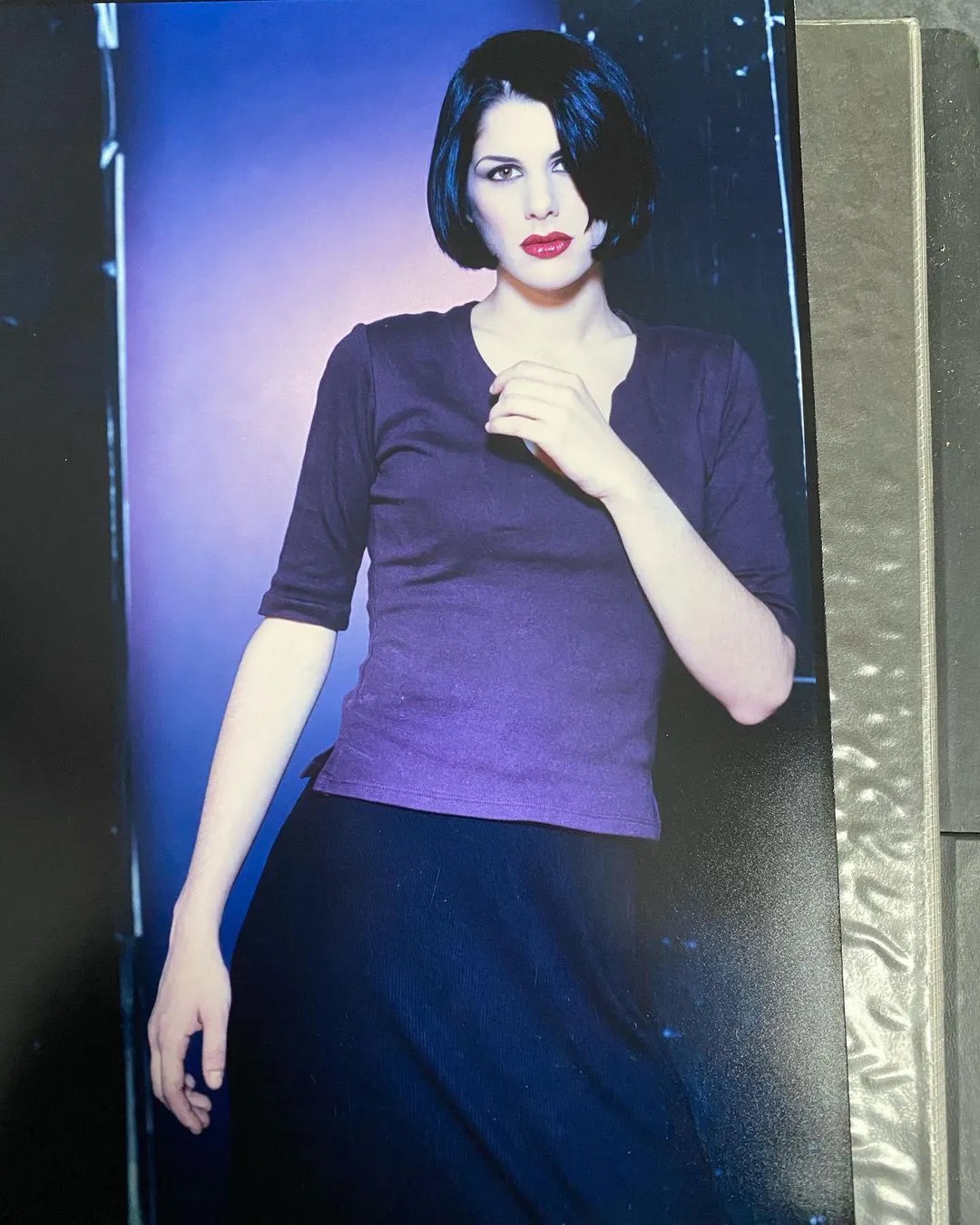

In this photo, up-and-coming fashion model Kathryn DeLorean is four months pregnant. She’s already had one change in career and residence—when her mother, world-famous model Cristina Ferrare, marched her into the country’s top agency and forced her to sign a contract. Goodbye coffee-shop job and boyfriend; hello, New York. The next decision was Kat’s. She quit modeling to give her child what she never had—a chance to grow up not famous.

Decades later, years after taking her husband’s last name, Kat asked her daughter’s permission to once again appear in public as a DeLorean. Her daughter said yes. Kat wants to do what her father never could: restart the family car company.

She’s planning to avoid small hotel rooms and cocaine dealers.

This January, Kat and Jason Seymour celebrated 19 years of marriage. Wanna go see Elvis? he asked in 2004. Into her F-150 they jumped, driving from their home in California to Las Vegas’s Little White Wedding Chapel. Vows exchanged, they got back into the truck and drove home.

To mark the anniversary, the couple had wanted to leave their three adult children and newly acquired farmhouse in rural New Hampshire for a getaway trip, but at the last minute, they decided to attend a car show in Miami instead. Their celebratory Instagram posts—one on Kat’s personal account and one on the DeLorean Next Gen Motors account, which Jason runs—feature her in a ball gown and fur coat, at the Motorcar Cavalcade in front of a DeLorean DMC-12, the only production vehicle to wear the family name. “My king,” she wrote in her caption. “My queen,” Jason’s post said, “love you more than there are stars in the sky.”

On this bitterly cold morning, Jason is in front of the farmhouse in a parka and work boots, in the property’s unpaved and thoroughly iced-over driveway. The battery in their heavy-duty Ford pickup, their daily driver, has gone kaput. To the left, covered in snow, are Kat’s treasured Pontiac Trans Am, “Babs,” and a late-model Acura.

From behind the front door comes a volley of barks—Grim, the yearling Dane, is excited to meet a visitor. Kat opens the door smelling faintly of nail polish. Clad in an ankle-length knit cardigan, a home-dyed rainbow ponytail trailing past her waist, she reasons with the crated dog: Thank you, yes, thank you Grim, good boy, it’s OK.

The two-story house, custom-built by an amateur, makes little sense. The mudroom-slash-foyer, accessing both driveway and backyard, is chilly and cavernous. To the right, a pass-through fireplace dominates the living room; stairs to the upper story are at left. Glass cabinets teem with memorabilia; in one of those cabinets, just beneath a collection of vintage coupe glasses, sit a pair of brown cowboy boots that belonged to Kat’s father, John, their scaly leather tops flopped to the side.

Up the stairs, past a hallway decorated with children’s artwork, is the carpeted bedroom Kat and Jason use as an office. Inside, propped against a wall, near a window framed by a Mickey Mouse back scratcher and vintage prints of 1950s Pontiacs, is the only Back to the Future II poster signed by John Z. DeLorean. A bundled curtain is thumbtacked to the ceiling above Kat’s lime-green Minecraft office chair, noise insulation for the podcast mic on her desk. On a corkboard nearby, coding shorthand jostles with a picture cut from a DMC-12 brochure, a poster from the local DeLorean club—North East Regional DeLoreans, or NERDS— and a page torn from a word-of-the-day calendar.

The page is for Thursday, July 1, 2021. The word is cabbage, v: to take or appropriate without right: steal, filch.

John DeLorean was acquitted of federal drug-dealing charges in 1984. The years immediately prior were front-page material. After abandoning a shot at the presidency of General Motors, then the world’s largest automaker, John resigned in 1973 to start his own car company. Nine years later, crippled by recession, the DeLorean Motor Company was bankrupt. Its desperate founder had done everything he could to save it—even, the prosecution argued, going so far as to meet undercover FBI agents in a cramped room in the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles and agreeing to ship cocaine into the country.

The trial lasted five months. John fought eight federal charges, including possession and distribution of cocaine. A full conviction would have condemned him to 67 years in prison. The jury decided the whole thing smelled like entrapment and declared him not guilty on August 16.

It’s hard to tell which member of the family had a worse experience in the years that followed. Cristina, Kat’s mother, left John exactly one month later. “No one’s talking divorce,” the family lawyer said, but one was official by April 1985. So was Cristina’s marriage to Hollywood producer and ABC head Tony Thomopoulos, whom she had married two weeks prior. Cristina got custody of her son, Zachary, whom John had adopted, and their biological daughter, Kathryn. Along with the fallout from the end of his third marriage, John faced a Detroit grand jury over misuse of company funds. At school, the children faced grade-schoolers armed with endless cocaine jokes.

The release of the film Back to the Future, on July 3, 1985, not a full year after the acquittal, and the subsequent ascension of the DeLorean automobile to pop-culture immortality, came tragically late. For Kat, the car represented something worse than a failed business: Every time she saw a DMC-12, she remembered a life and a family that no longer existed.

“I had a really difficult relationship with the car,” she says. “If there was an iconic representation of your life falling apart, would you park it in your driveway?”

Six years after the movie, when Kat turned 10, her last name still rhymed with crime. In their 1991 track “Sometimes I Rhyme Slow,” New York rap duo Nice & Smooth lit the jokes afresh: And furthermore, I’m not DeLorean, I don’t deal coke and you’re making me broke. As John retreated to a family house in Bedminster, New Jersey, Cristina sallied back into Hollywood, where her ex-husband had once been one of the biggest names in town.

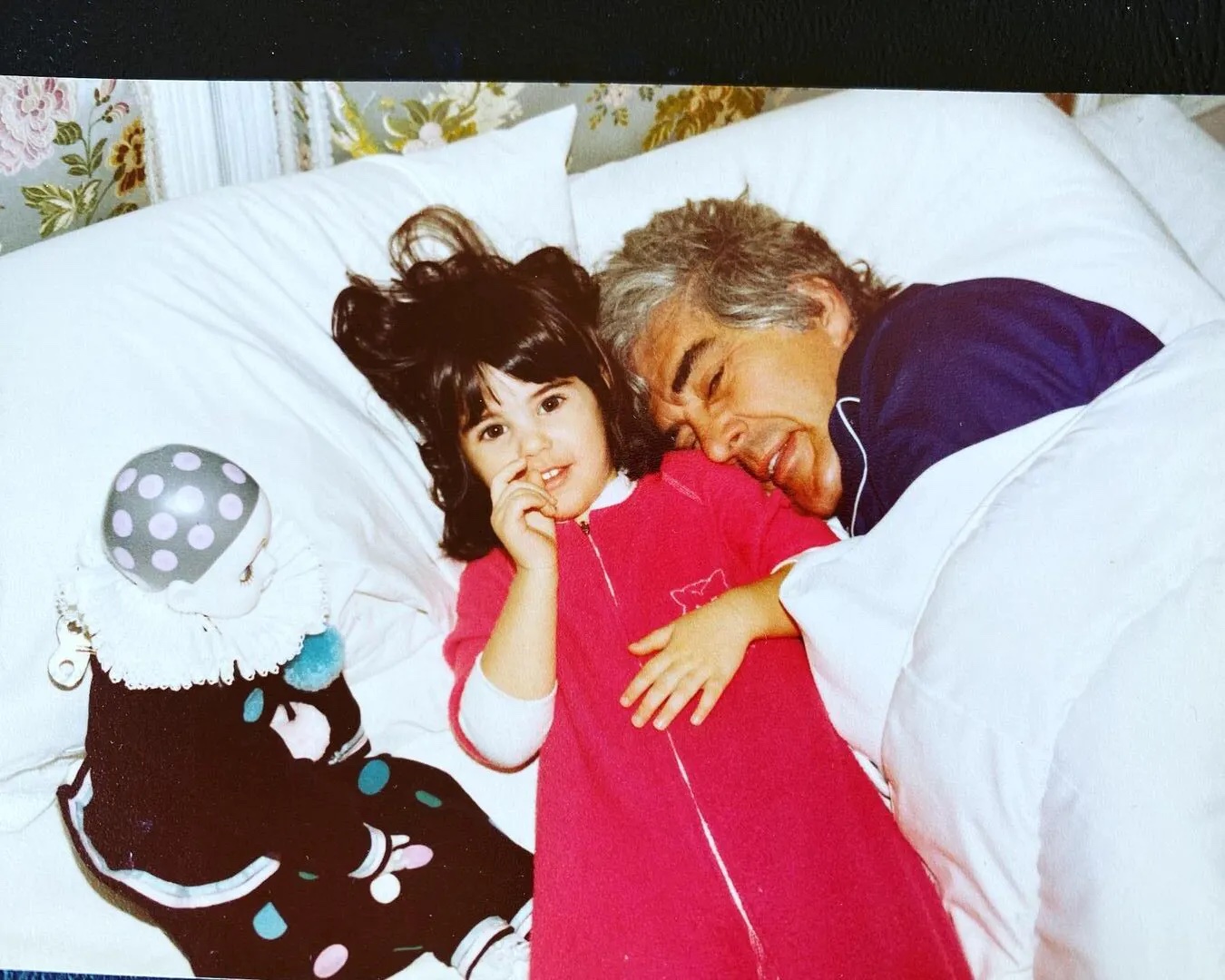

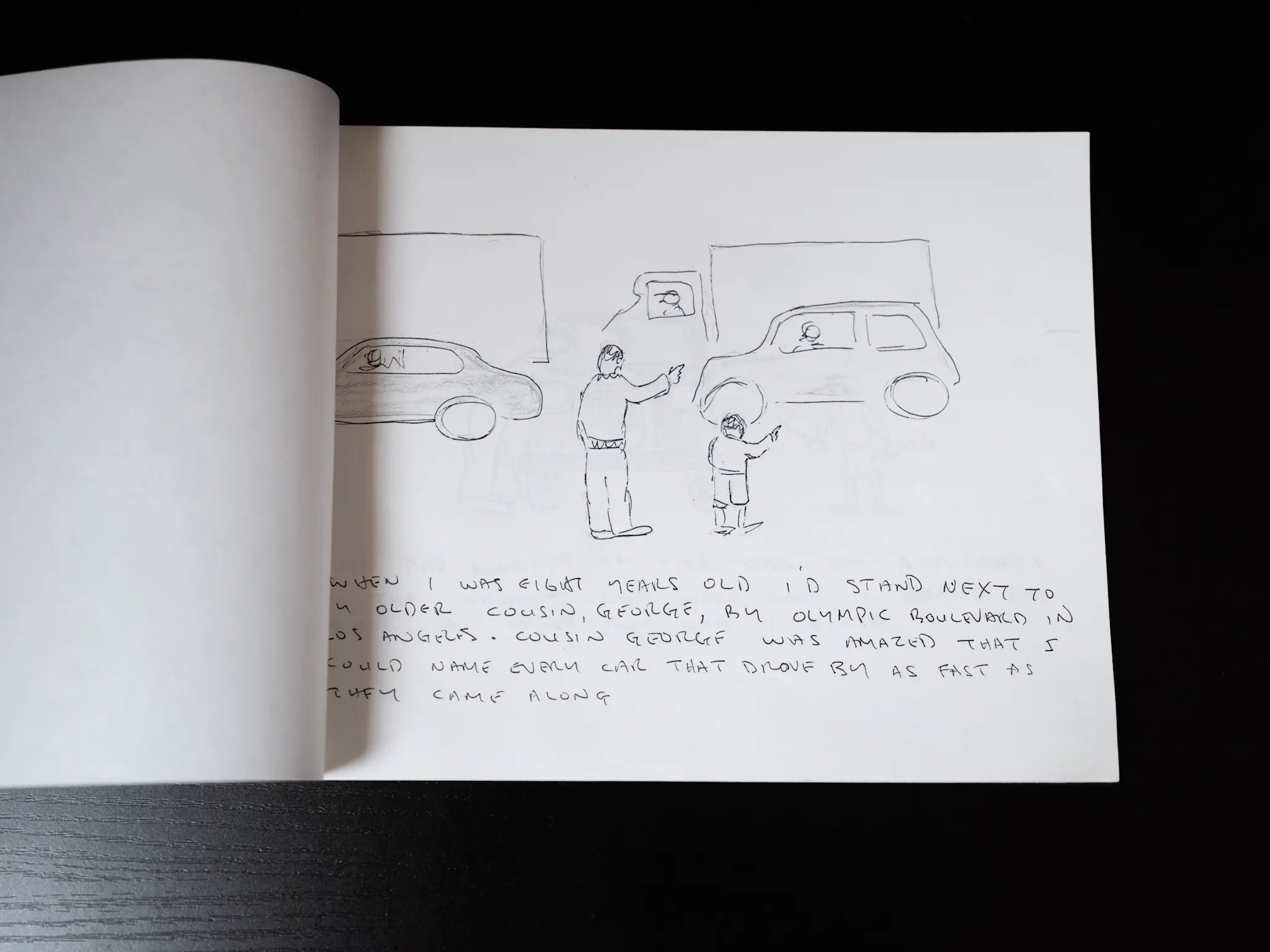

Kat shuttled between East and West, father and mother. Life in Los Angeles was dinner parties and red carpets; one Thanksgiving was a 75-person affair with Henry Winkler and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Her mother allowed Kat only two 10-minute phone calls to her father per day; Kat won more time by asking his help with her math homework. By her fourth-grade graduation, she had finished the ninth-grade geometry book. Teenage Kat found L.A. glamor exhausting, wanting only to hang out with her dad in New Jersey, on his 454-acre estate—“my own private continent,” she says. East Coast life couldn’t have been more different: jeans and fishing and dirt bikes and carpentry. And dogs, always dogs.

Work hard, her dad taught her, and you can have whatever you want. If Kat wanted more than one new game a month for her Nintendo, she had to work on the farm. She baled a lot of hay. That was also when she started dyeing her hair wild colors, age 12 or 13. Her dad supported her but pulled no punches. “He used to tell me that I looked like an asshole. His point was, be who you are, but understand how the world will perceive you.” Father then would drive daughter to New York to buy Manic Panic hair dye from Tish and Snooky’s, because it was the ’90s and that was all you could get.

Along with a sense of the power of names came a drive to earn what she had. In her mind, her first car wasn’t the Camaro Z/28 for which her mom had loaned her $20,000; it was the 1998 Trans Am she bought with her own money and still has. More than her modeling career, which funded that purchase, she talks about her 20 years at Bank of America, seven of which were spent on a cybersecurity “red team.” One of her responsibilities was to hunt down weakness in—i.e., hack into—the bank’s network. She takes extra pride in that part of her life: “I did it without leveraging my name.”

Kat had joined the bank after quitting modeling to give birth to her first daughter. She was a senior lead on the weekend night shift when her boss asked her to attend an annual meeting of the bank’s upper execs. Should she dye her hair back to its natural brown, she asked? Screw the dress code, he said; you’re my rockstar, anyone who objects can talk to me. So in she walked, swinging four feet of purple ponytail.

That boss understood her, she says. She has never stopped dyeing her hair.

In the office, atop a vintage Ms. Pac-Man video game table, are a set of gold-rimmed china plates that belonged to her father, strewn with pizza crusts from the family-owned place down the street. She sits cross-legged on the floor a few feet away. Nine of her fingernails are purple; the thumb wears a coat of a Korean-made polish that “cracks” in large flakes to reveal metallic copper. (“My pride and joy.”) In a corner rest two large plastic cases of nail polish, part of a meticulously preserved collection that took years to amass and was mostly scrounged on clearance. Showing it to a reporter required some insistence.

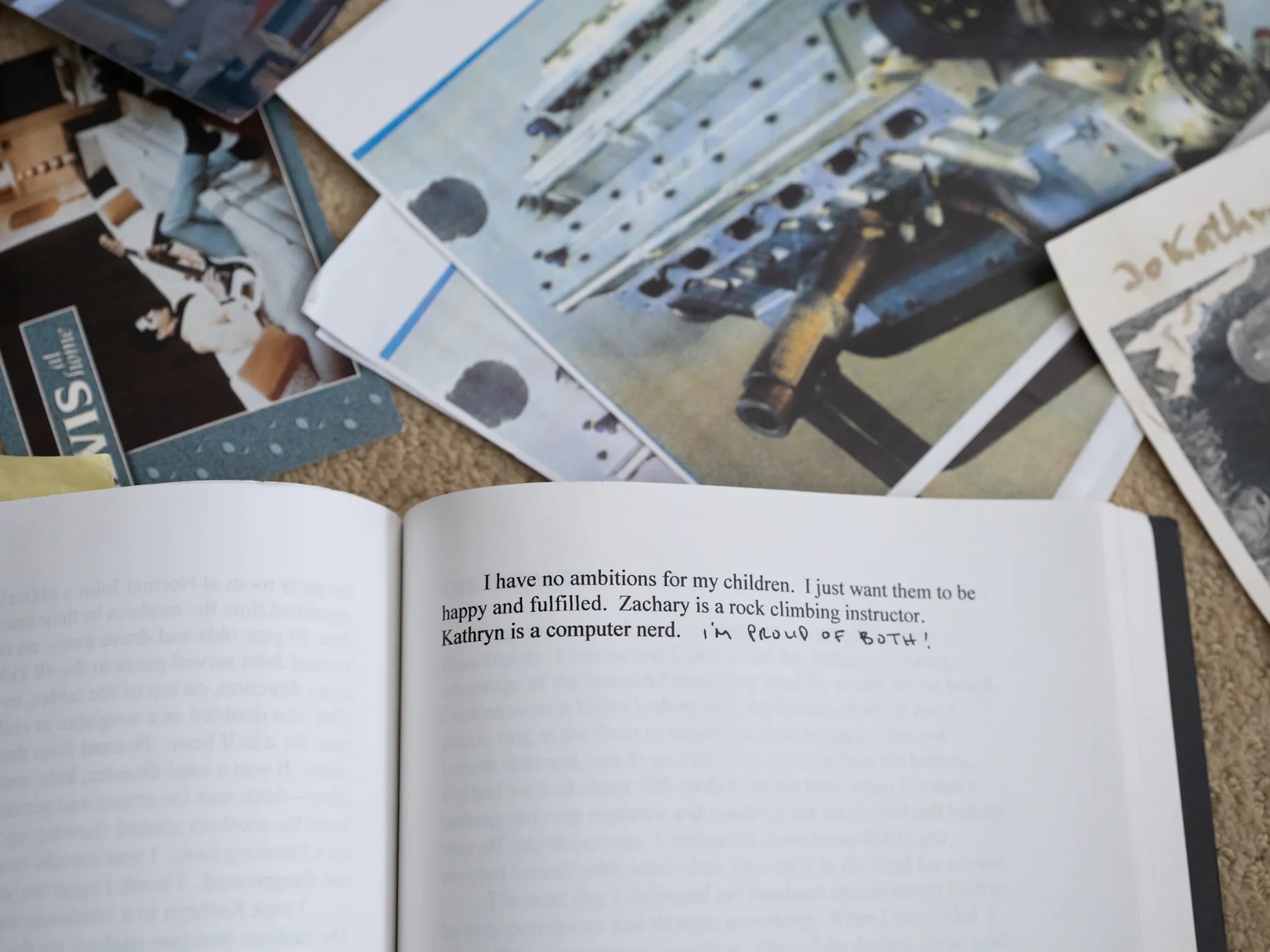

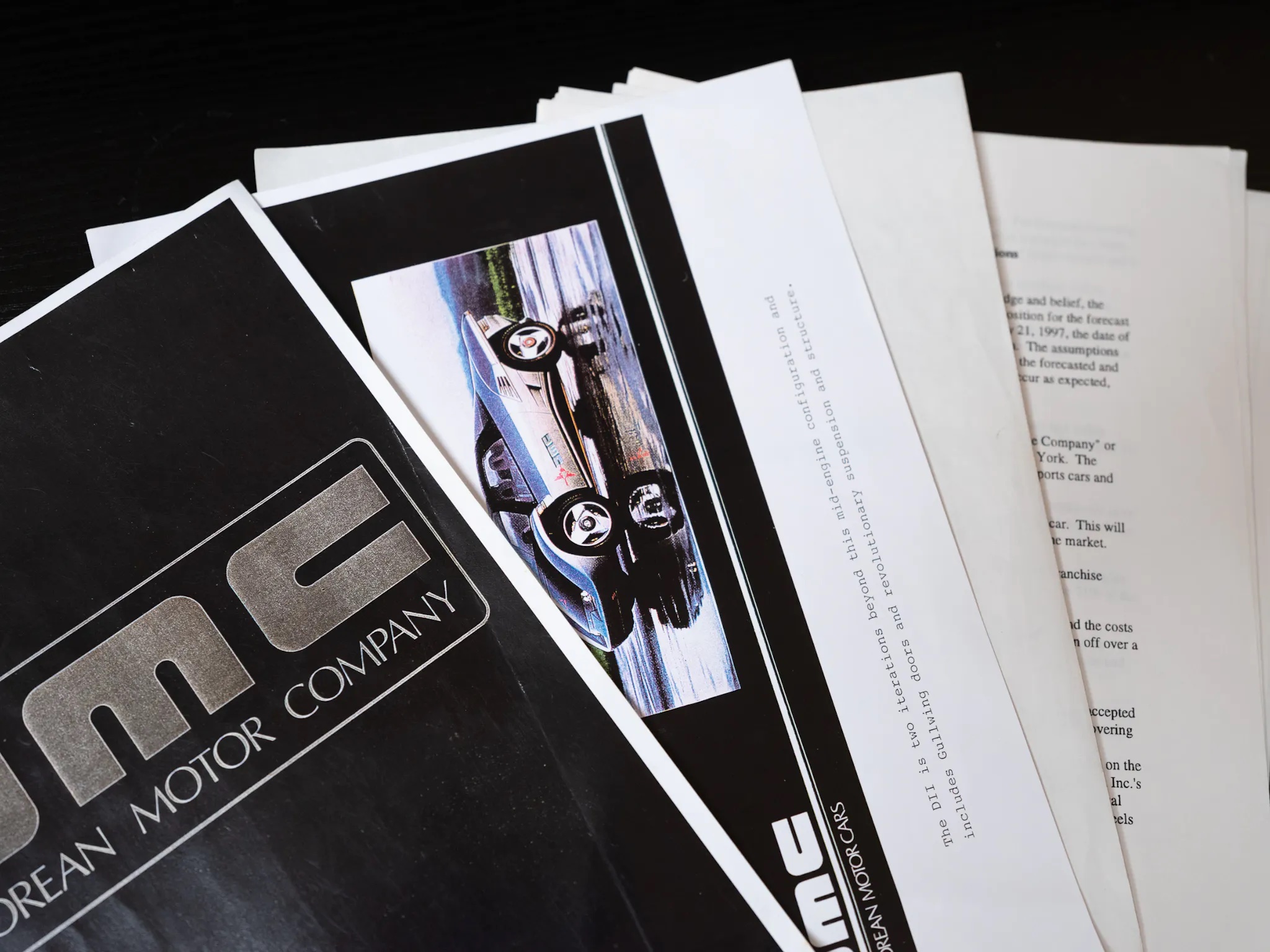

On the floor are bins of memories—Polaroids upon Polaroids, her father’s last driver’s license, People and Life magazines featuring him and his family, full-page reprints from her modeling portfolio, pictures of engines that never made production. John’s business plan for starting another DeLorean car company, whose timeline Kat has been following nearly step-for-step. (Last week: Visit manufacturing facilities.) She thumbs through a bound sheaf of paper—John’s unpublished book.

“If you’ve come across something about my mom, don’t read it.”

She holds out a photo of herself, young and tiny, playing gin on a couch with her father. When Kat got her first apartment, he gave her that couch. Its upholstery was worn in two spots, one where each had sat.

“Then my ex-husband set the couch on fire,” she notes. The conversation lulls for a bit.

She feels like she knew her father, she says, but is realizing more and more that she didn’t know John DeLorean. “In every story he told me, my dad left out the part where he changed the world.” When GM leadership wouldn’t listen to his arguments about the necessity of safety equipment, for example, the star executive shared the frustration with his daughter. What he didn’t mention, what she discovered years later, was how airbag research he had conducted as an independent consultant in the 1970s helped debunk Detroit manufacturers’ artificially inflated cost estimates for the technology, featured prominently in federal hearings, and helped make the bags mandatory on new vehicles.

In 2000, at 23 years old, Kat started going to car shows and accepting the occasional invite to speak. One day, she returned from a show determined to get her 75-year-old father out of his condominium. He had declared personal bankruptcy in 1999 and needed distraction. The idyllic New Jersey estate was gone, sold to a golf-course developer. The $15.25-million price covered less than half of John’s debt.

“Dad,” she said, “You got to come with me. You got to see how much people still love you.” Daughter dragged father to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, the site of a gathering called The DeLorean Car Show, where they were received like celebrities. On the plane home, “I started to see not what the car was, Back to the Future and all these other things. I was able to see what it represented for all those people.”

John died of a stroke five years later. His daughter, then 27, wasn’t there; she hadn’t been told.

“It feels like I’m on this journey, right now, of getting to know his life.”

Save the year her first daughter was born—Kat sent a note of explanation—she has not missed a running of that DeLorean show since. DMC-12 fans, she said, were great, not always car people, a “statistically significant ratio of good humans to normal humans.”

As she listened to story after story from those who had longed to own a DeLorean as a kid, then saved for years to make it happen, the car took on new life. She realized it represented a dream. “Not my dad’s. Everybody’s.”

Before harboring any ambition to run a company, she began hunting for an unregistered URL. She wanted a website for hosting memories of her father, where anyone could share a story or quote. One day, a message came in from former Bugatti designer Ángel Guerra, a friend: He had registered a domain for fans to write her dad “Dear John” letters—was she interested? Having discovered that a Texas-based company was buying up DeLorean domains, she decided to act, told Guerra that yes, the family wanted it.

At the same time, in her day job, she was stepping into more of a training role. She wanted to mentor, to foster the kind of inspiration that had once fired her. When her daughter’s boyfriend, Ian, shared his frustrations about pursuing a career in the automotive industry, she agreed to let him restore her Trans Am as a capstone project for high-school shop class. If he did the work, she’d buy the parts. Past and present began to collide. Connections from her father’s world, reaching out to share stories on the legacy site, asked what she was up to. She would tell Ian’s story, to illustrate her passion to help kids like him get jobs in U.S. manufacturing, college degree or no. Wouldn’t it be cool, she’d say, to start a high-school program where kids built a car start to finish?

Offers began flooding in, for design, engineering, mentorship, whatever skills were needed. DeLorean’s daughter was starting a car company, right? Before she knew it, she was. The choice brought her into touch with industry heavyweights, people like Bill Collins, John’s right hand in creating the Pontiac GTO, or Fred Dellis, who, in a 1997 business plan, John names as future President of DeLorean Motor Company, Incorporated. Kat calls Fred her ace in the hole. (“He’s checked up on me my whole life since my dad died.”)

Kat was finding answers—and new questions. When she noticed that DeLorean DMC-12 VINs began with number 500, she reasoned that there must be 500 missing cars. She texted Bricklin asking where they were. I have no idea, he replied, followed by a wink emoji. The memory pulls rare profanity.

“That f***in’ dude! Either you know or you don’t. What’s with the winky face?”

Her father’s mix of hustle and humor is reflected in his friends. Bricklin texts Jason at four in the morning every day. “I read through it, and I’m like, ‘Jackass, you need to text him at the same time, every morning at an early hour.’ Jason’s like, ‘Well, I’m busy. I’m taking the dog out.’ I’m like, ‘That’s the right answer . . . He wants to make sure you’re disciplined enough to succeed.’”

Jason began replying to Bricklin at 5:00 each morning. At four the next day, just as Kat predicted, another message always comes.

“Yes,” her voice bursts. “They’re all f***ing with my head while I’m having”—she begins clapping off-time as she speaks—“a car company”—clap—“fall out of the sky, in my lap”—clap—“with these old men screwing with my brain.”

Downstairs, the Great Dane fires off a round or two as punctuation.

“It is a wild journey that I am on.”

In 2019, Tamir Ardon produced Framing John DeLorean, a 109-minute docudrama starring Alec Baldwin as John and 20 years in the making. Kat had counted Tamir as a friend, and, in the wake of her experience with the DMC-12 community, consented to help with the project. A single scene ruined their friendship. In the film’s final moments, Baldwin and Morena Baccarin, as Cristina, reenact a supposedly historical scene from the 1984 trial. As DeLorean angsts over his tie, his wife pleads for help in consoling their children, who fear their dad will go to jail. Children and wife are doe-eyed and pitiable; Baldwin’s John is selfish and dismissive—in Kat’s eyes, a monster.

When she confronted Tamir, he admitted the story came from Cristina. He added the children for effect.

“I continually ask him, why didn’t you make the movie you wanted to make? And I know the answer: Hollywood does what Hollywood does.”

All Kat wanted from Tamir, she says, was an apology; when one did not come, she hung up the phone. The two haven’t spoken since, though she did attend his movie’s premiere. “I don’t want to focus on things that I can’t change, that have no positive impact on my life. I let that go.”

Relationships matter; old jokes, she can deflect. To the internet commenter who asked whether her new DeLorean car will come with “the brick in its trunk,” she replied, “No, but we want to make snow tires an option.”

“What else am I going to do? Pretend it doesn’t exist? The age we live in, the truth doesn’t matter. You’re not going to change somebody’s mind with anger, and you’re just going to further the story the way people want to believe it. Unless you approach them with compassion and thoughtfulness. It’s not their fault they don’t know the truth. It’s hard to find.”

On a stool in the kitchen, in front of a painting of a DMC-12 done by a fan, Kat shifts her weight, straightening back and neck toward the camera. The knit-sided booties she wore earlier have been swapped for cowboy boots, a subtle nod to her father. She glances left, toward the mudroom. Jason stands there, expressionless, in matching boots, behind the metal baby gate that keeps the Dane out, arms crossed, blue eyes fixed on her.

She giggles, knuckles to her mouth, then primps. “Does my hair look OK?”

A beat. “No.” Jason strides over, smoothing her long pony before laying it neatly over her shoulder. As she tips her face up, eyes nearly shut, he gently tugs a few strands of hair, framing cheekbones and jaw, before returning to the edge of the room.

It’s hard to imagine this taciturn, dry man—who married Kat only a month after meeting her, as if on impulse—asking John Z. DeLorean how he came up with the flux capacitor. Jason had offered the question in earnest, referencing a Back to the Future prop, with Kat’s encouragement. She knew her dad would find it hilarious and not miss a beat. That night, as the newlyweds left, Kat’s father whispered in her ear that he really liked Jason, and knew she would be OK.

The two met at a work party around the holidays. Kat was a single mom to a child with special needs, nearly broke, untangling from what she refers to only as a “bad relationship.” She told Jason that she drove a truck. No, Jason answered, women drive tiny, cute cars—a Jetta or a Beetle. So she walked him out to the parking lot and her Harley-Davidson Edition F-150. At the end of the party, they were still in that lot, leaning over an engine bay.

Kat made it clear she wasn’t ready to date. Jason offered no resistance. Days later, she found a Christmas gift on her desk, a Hot Wheels model of a Harley F-150. Jason didn’t acknowledge the gift, but he saved the receipt. Years later, as an anniversary present, he wrote her a poem on the back.

Their upbringings were vastly different. While she was being dressed up like a doll for Hollywood movie premieres, he was watching camel races in Nevada. Somehow, each was exactly what the other needed. Kat used to hate shopping; now, she wears sparkles or sweatpants whenever she feels like it, sometimes does her makeup at the end of the day on a whim.

“I wish I could bottle him and give him to every woman—to feel the way he makes you feel, because he really …” Her voice catches in her throat. “It took a lot.”

Light drenches the kitchen. It pours through the skylight, reflecting off the snow outside and onto the indoor herb garden. The room is Kat’s favorite, despite being under-insulated and colder than the rest of the house. She imagines it with white cabinets. For now, though, they’ve stuffed steel wool into the crevices, to keep heat in and rodents out, because money that would have gone to a renovation has been earmarked for DeLorean Next Gen Motors. Somehow, she says, it’ll all come back in the end, and they’ll be OK. Spread across the center island are tokens of family history. A scale-model DMC-12, the Piaget watch given to her father by GM’s Pete Estes, her brother’s toddler-size bomber jacket, photos from her modeling portfolio. She sifts through the latter, then points to her favorite shot—Kat looking down and away from the camera, one hand pushing through short, dark hair. She touches the corner of the photo with finger and thumb, and smiles. Find out more

Report by Grace Houghton for hagerty.com