Exactly thirty years after Ayrton Senna’s tragic accident, his nephew Bruno took on the hillclimb at the Goodwood Festival of Speed in a McLaren Senna. And we got to sit in the passenger seat.

Bruno Senna sits in his McLaren, looking at the display, entering the track data. The car hums at idle. Someone shouts something unintelligible. He looks up – the car in front of him has already taken off. Time for him to go, to get on the grid. He steps on the gas, and the McLaren fires a sharp volley of V8 power into the sunny sky. But it doesn’t move even an inch. The display reads “N” for neutral in large letters. The car isn’t in gear. There must be around fifteen thousand cellphone videos of the scene. Bruno pulls on the right gearshift paddle, first gear, another tap of the pedal. The McLaren still won’t budge. This time, it’s the electronic parking brake. He releases the brake, drives off, and waves to the audience. He has to laugh. That’s something that sets him apart from many of the other prota-gonists in the racing circus, who would have handled the situation with much less humor. Asked what Ayrton would have said if he had seen that, Bruno stares off into the distance for a moment and then replies: “He would have shaken his head and called me pé-de-breque. That’s Brazilian and means something like ‘slow driver’ or, more humorously ‘Mr. Foot-on the-Brake’.” At this moment, Bruno does indeed resemble Ayrton. Only that he seems younger, which is astounding, considering that at forty he’s already six years older than his uncle ever was.

Bruno Senna is driving the hillclimb at the Goodwood Festival of Speed in a McLaren Senna. And we’re along for the ride. McLaren calls it “Senna meets Senna”. In the year marking the thirtieth anniversary of Ayrton Senna’s tragic fatal accident, McLaren is paying tribute to perhaps the greatest racing driver of all time. Our plan: a fast-paced interview, seeing as the hillclimb normally lasts only a minute or so. Though actually, we have plenty of time. After all, it takes time to organize all the cars and drivers. So we undo the six-point safety belts and swing open the scissor doors. The McLaren has no air conditioning, it’s a pre-production vehicle owned by McLaren Automotive with a plaque in the door sill bearing the inscription “000 of 500”. The car has over ten thousand miles on the clock. Nothing but hot air comes out of the blower. Bruno acknowledges our comment that Ayrton would certainly have liked that with a skeptical look: “No, he wouldn’t have. Definitely not.”

Why aren’t you driving the hillclimb with the Senna that was specially painted for this tribute, standing there at the front of the stage?

I had the same question. Apparently, McLaren is afraid I might damage the car.

Because you’d drive it all out?

[Short diplomatic pause] The first day is always a bit tricky. The track is still full of sand and dirt from the set-up. The tires are cold. The grip is certainly not the best. I think we’ll go a maximum of eighty percent.

Ayrton famously once said, “If you think I’m fast, you should see my nephew.” What did you think when you heard that?

No pressure, right? [laughs] But seriously, I think when I first heard that, I was just starting my racing career. I don’t think that’s exactly what I needed to hear at that point. But it also gave me so much encouragement that someone like him would think that of me. I remember when I was a kid and we were racing go karts together and I could match his lap times. Obviously, I had that competitive spirit from a very young age.

You could match Ayrton Senna’s times when you weren’t even ten years old? He must have taken his foot off the gas a bit then, or not?

What are you implying!? [Bruno Senna has to laugh. This insinuation is obviously new to him.] Back in São Paulo we had a track with a straight that was around 350 meters long, quite a distance for karts. You drive at full throttle and at the end there’s a left-hand bend. To drive it perfectly, you only had to briefly ease up on the throttle. I told Ayrton that. He said that was nonsense, the corner would be perfect. And to prove it to me, he got on his kart, drove off and you could hear from the sound that he didn’t ease up on the throttle. He ended up flying off the track, straight into the fence. He came limping back and said, “You’re right, full throttle won’t do.” Losing was not an option for him, especially not against children.

It’s got to be at least a little irritating to be asked the same questions about Ayrton over and over again all your life. But is he tired of it? No, he’s a really friendly person who easily dispels any worries that you might be boring him with your questions. A marshal briefly drops by, the two know each other, a quick chat, then he answers the next question about Ayrton Senna.

What spontaneously comes to mind when you think of him?

Christmas. Ayrton came by. My sisters and I were excited about the presents and we were running around the house. Ayrton told us to be quiet, but he was also a lot of fun, he played around, made jokes, pulled pranks on everybody, wanted us to experience things and form our own opinions. He did that in so many ways, with go karting, engines, mechanical stuff, jet skis . . . He was always trying to teach us something in a fun way. He was my hero and my role model.

After his death, you took an almost ten-year break from racing – at a point in your career where others are busy laying the groundwork for their future . . .

It was difficult to stand up to the family. I missed driving, especially when I saw others going professional. When I was sixteen, seventeen, I was working with my grandfather at one of our car dealerships. I was also studying business administration, which I absolutely hated. My mother saw how much I missed racing and spoke to Gerhard Berger, who helped me.

Does that mean your mother supported you despite everything?

She gave me all the support she could, despite being extremely concerned about safety and her personal feelings about the politics in F1. I find it amazing that she was able to put all that family history aside and give me a real shot at doing something she was so fearful of.

What can you tell us about the influence that Gerhard Berger had on you?

He told me a lot of stories of his time with Ayrton, not just about racing. But even today, I still can’t tell every one of them. That was always very entertaining. Gerhard was also very direct and had quite interesting perspectives. Normally, when you have the family pushing you through something, they’re always encouraging you and always trying to soften the blows when things aren’t going so well. Gerhard was different. He didn’t tolerate any bullshit, you know? We did some testing and he said, “Yeah, you’re quick, but you’re all over the place as well.” And he was right. And then we did these races in Formula BMW, and he said, “These kids, they’re crashing too much. They’re making too much of a mess. You’re too old for that. If you have any chance of doing anything special, you need to go straight to Formula 3.” So that’s what I did.

And do you think he was right?

Looking back, it’s really difficult to say. I was already twenty, while the kids in Formula BMW were like sixteen or seventeen. I was lacking experience, so what I had to do was to get that experience quick. Maybe I would have won more in Formula BMW than in F3, but getting into the top five meant that I was doing well.

Suddenly things are moving. A McLaren GTS rolls up in front of us. This really is it, the cars are being sent out onto the track one after the other. “Put your cellphone away,” says Bruno Senna briefly as a marshal approaches the car. “She’s really nice, but you’re not allowed to film during the hillclimb.” – “And right after the start?” Bruno just grins. The result is one of the shakiest cellphone videos ever.

We’ll save the question of how Ayrton’s death affected his attitude towards risk until after the hillclimb. A marshal gives the starting signal. Bruno Senna goes full throttle. The McLaren responds with a magnificent burn-out and a huge cloud of smoke that drifts behind us through the narrow avenue of trees, a bit like those maniacs who speed through the desert during the Dakar Rally. Not even sixty seconds later, the fun is over. Then we have to wait again, this time at the finish line.

That question about risk just answered itself, didn’t it?

When you’re in the car, you understand the risks that you’re taking. Even as a kid, the younger you are, the less you think about the risks. I went off the go kart track enough to know how much it hurts. I’ve seen how things have changed and how the safety level of the racetracks was quite different back then. So I respected the danger a bit more, probably because I had this experience.

Bernie Ecclestone was batting for you at the time. And then you made it into a Formula 1 cockpit.

There’s a very funny back story to that. I mean, we didn’t have any decent simulators outside of the F1 team realm back then. Going to new circuits when I was racing in junior series was a huge learning curve, and because I started late, a lot of the time I was driving new race tracks and having to learn from scratch what other drivers had been doing for years. I was doing British F3 testing the day before flying to the Australian GP. I drove straight to Heathrow carrying my F3 seat with me because I had no time to make one in Australia. So I flew to Australia with my F3 seat in the overhead bin, still all sweaty from the testing. In the end, my flight was delayed as well. I landed in Melbourne, and we rushed straight to Albert Park. I ran through the park with my luggage, my seat and everything, got to the paddock, put my race suit on, put the seat inside the car, adjusted my belts, went straight to the practice session. That’s how that weekend started for me. I won three out of four races in the Australian F3 car. The first time I got into an F1 car was when I drove for the Honda F1 team at Barcelona at the end of 2008.

That’s nuts!

Complete madness. That was my first experience of being at a proper F1 weekend. It was amazing, and I did well too. Obviously, that was my objective: to be in F1.

It’s pointless to speculate how your career would have gone without that break. Do you have any regrets?

No. That’s Formula 1. There are only around twenty slots available each year. Let’s take Honda as an example. Ayrton won all three of his World Championship titles with Honda engines. So obviously, I was completely motivated to race Formula 1 for Honda. I was driving tests for them in Barcelona at the end of 2008, but shortly after that they withdrew from Formula 1. Ross Brawn then founded Brawn GP with Jenson Button as number one driver. The second cockpit still had to be filled. That was my chance! We had lots of meetings. But they didn’t know exactly what they had in their hands with the car because everything was new, everything was very late in development. They also had to adapt the car to the Mercedes engine because Honda was out. That definitely was a big challenge for the team and I respect that. They had to make a decision between me and the very experienced Rubens Barrichello, who had spent years driving alongside Michael Schumacher at Ferrari, in the same team with Ross Brawn. So maybe if we had done the second test in Jerez before Honda pulled out, I could have shown a lot more, But I only had one day in the car so can’t blame him, honestly. They went with the safe option.

We’ve already mentioned Berger and Ecclestone . . . has your name opened a lot of doors for you?

At the end of the day, what matters to the teams is that they want to win. Anything else is irrelevant and shouldn’t be important. In my first season in GP2, I was racing with Arden, sponsored by Red Bull. Helmut Marko [former racing driver and since 2005 head of motorsport at Red Bull Racing] was there. I was leading the GP2 for a couple of races, but the car wasn’t competitive. Marko came to me and told me I would never be good enough for Formula 1. And that spurred me on to prove him wrong. During my second season, with a competitive car, I fought for the championship and came in second place. Ron Dennis [former team principal and co-owner of McLaren] straight up said to me I was too tall to be a racing driver. Frank and Claire Williams [former team principal and founder of Williams F1 and his daughter] were always good to me. We talked a lot, and I actually drove for them in 2012. But Formula 1 is all politics and business. It’s not a sentimental feel-good kind of place.

You won the GP2 in Monaco in 2008. What was that like?

A lot of people asked me if I was thinking about Ayrton when I was racing or when I was on the podium. But during the race you’re so involved that you don’t really have time to think about someone else when you’re driving the car. But when I was standing on that podium in Monaco, that sort of brought back some real memories. Because it’s such a different place, right?

Several marshals come by to talk to Bruno Senna, and in between he gives a quick television interview for the Goodwood organizers. Bruno loves the festival, says it’s always great fun to be here, and that this year, for the first time, they put up some signs after the bridge showing the distance to the bend in fifty-meter increments, which is fantastic. Then a shrill whistle blows. That’s the signal to get back in the cars, everyone has to go back down to the paddock. This time, we don’t have to wear our helmets.

There’s another great quote from Ayrton, where he said, “We’re all kids. Just as you get older, the toys change.”

Yeah, definitely. His life was so serious most of the time, with all the competition, and he was so dedicated. But when he got home, he could be a kid again. That was his way of getting out of it and switching off.

Was he a hero?

In Brazil, he was and still is a national hero. He was an inspiration not only to the rich, but also to those people in Brazil who don’t have as much. His achievements show that you can do anything if you’re dedicated enough.

And what is his legacy?

Apart from his racing legacy, there’s the matter of safety in racing, which continued to improve after his death. There’s also the work of his foundation in Brazil. The foundation gives millions of children the opportunity to have an education and to potentially change the country for the better. It’s that legacy that I would like to continue in his name.

Bruno Senna parks the red McLaren Senna in the supercar paddock. A few fans come by and ask for autographs and photos. But Bruno Senna has to go, he has an interview at McLaren. “Goodwood is amazing. I’ve been coming here for twenty years. The people here are so excited! Ayrton definitely would have liked that.”

BRUNO SENNA was born on October 15, 1983, in São Paulo, Brazil. Following his uncle Ayrton Senna’s fatal accident, he put his own racing ambitions on hold out of consideration for his family before relaunching his career at the age of twenty. After getting his start in Formula BMW and GP2, he went on to compete in forty-six Formula 1 races for three different teams between 2010 and 2012. He has also contested Le Mans eight times and has competed in Formula E.

Text & Photos: Matthias Mederer · ramp.pictures

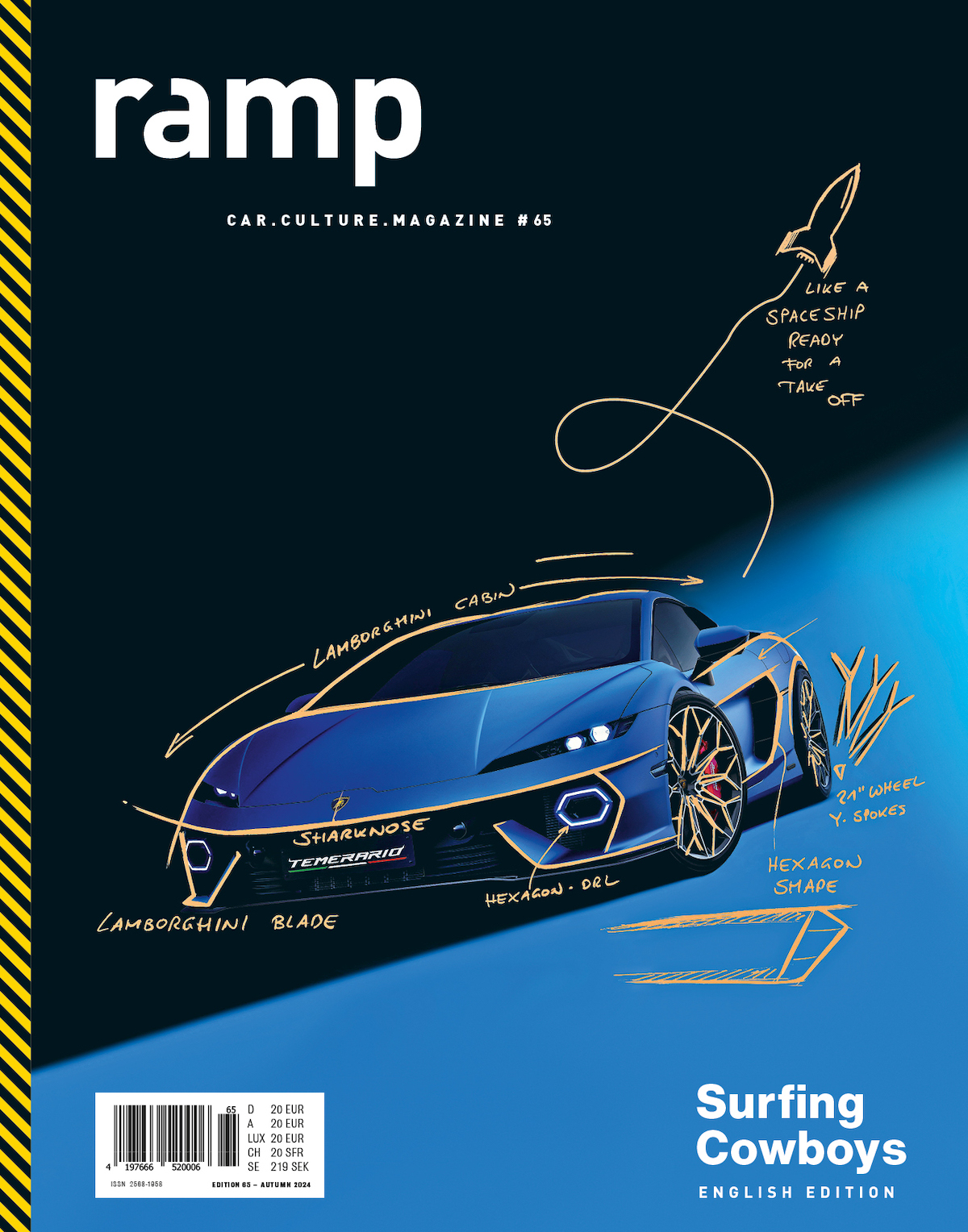

ramp #65 – Surfing Cowboys

If you think “Surfing Cowboys” refers to neoprene-clad prairie riders or surfers wearing cowboy hats, you’re slightly off the mark in this case. In the latest issue of our Car.Culture.Magazine, it’s about the meeting of two quintessentially American archetypes, both embodying a deep longing for lived independence and untamed, self-determined freedom. Find out more