The arrival of Ford at the Le Mans 24 Hour endurance classic in 1964 created press coverage as never before as the giant American corporation crossed the Atlantic to do battle with the all-conquering Ferraris. It was billed as a conflict between corporate power, backed by huge financial muscle, against a considerably smaller company, but one with experience on its side. Ferrari knew how to build winning cars and had many years of competition to call on; sports car racing fans knew something special was brewing.

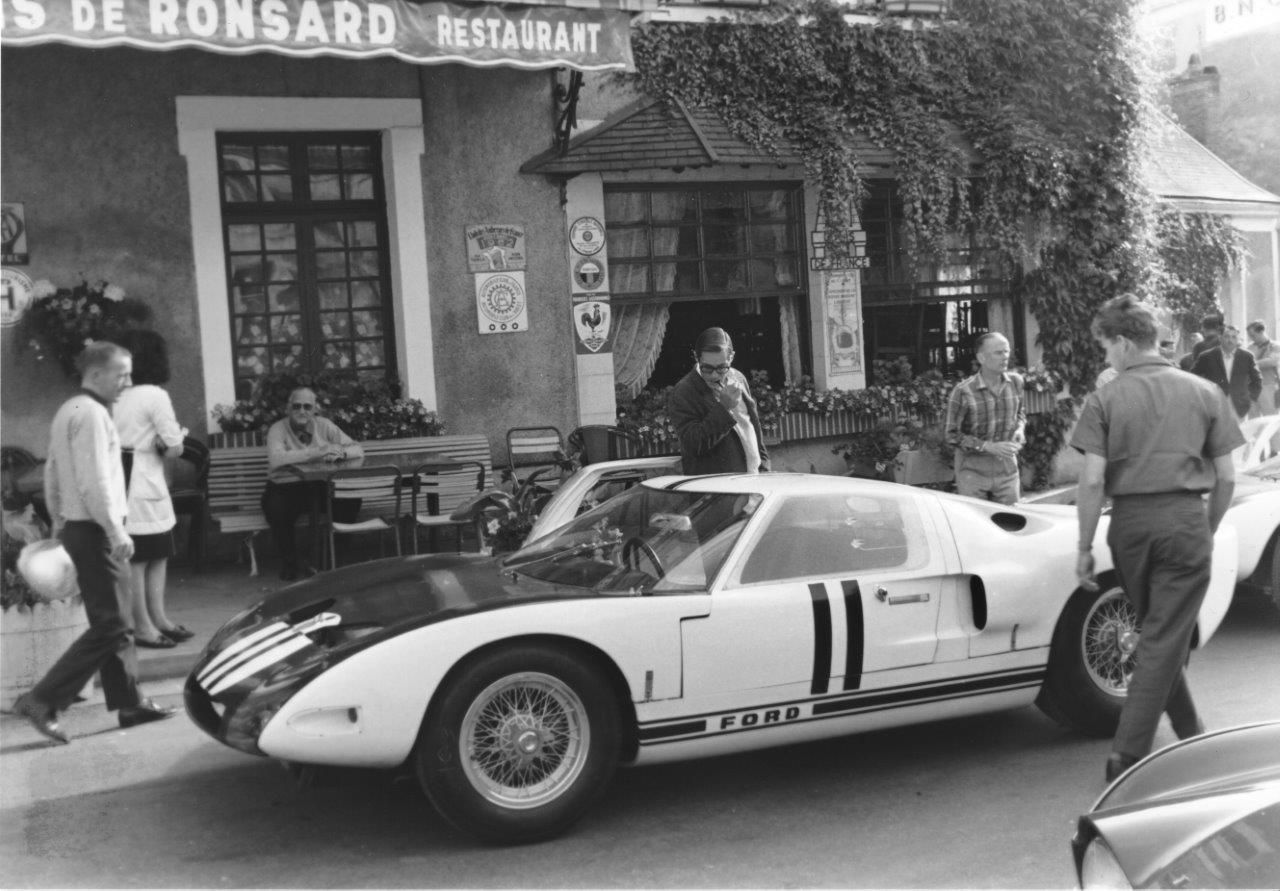

The prototype sports car responsible for Ford’s reputation faced a daunting challenge; initially called the Ford GT (before it evolved into the GT40, simply a reference to its height in inches), it arrived in a blaze of Ford-generated publicity that no new race car could be expected to live up to. Only the advertising ‘creatives’ and senior Ford executives (who had never heard of Le Mans) thought the car would steamroller the opposition; motor racing people knew better.

Ford approved the sports car project in March 1963 and appointed a team of senior managers to oversee it; they quickly discovered the scale of the task. By now Ford had installed computers at its headquarters in Dearborn to aid its design programmes and they used a promising new mid-engine design from the British race car manufacturer, Lola Cars, as a base from which to develop the GT. A deal was agreed with the owner of Lola, Eric Broadley, and the first prototype was built in his factory. Within months, a Special Vehicles Operation had been created and new premises acquired in Slough. Ford accepted that the UK had an experienced workforce capable of building a race car, plus it was closer to the European mainland where many of the world championship races would be held. Making use of this experience would save time and money.

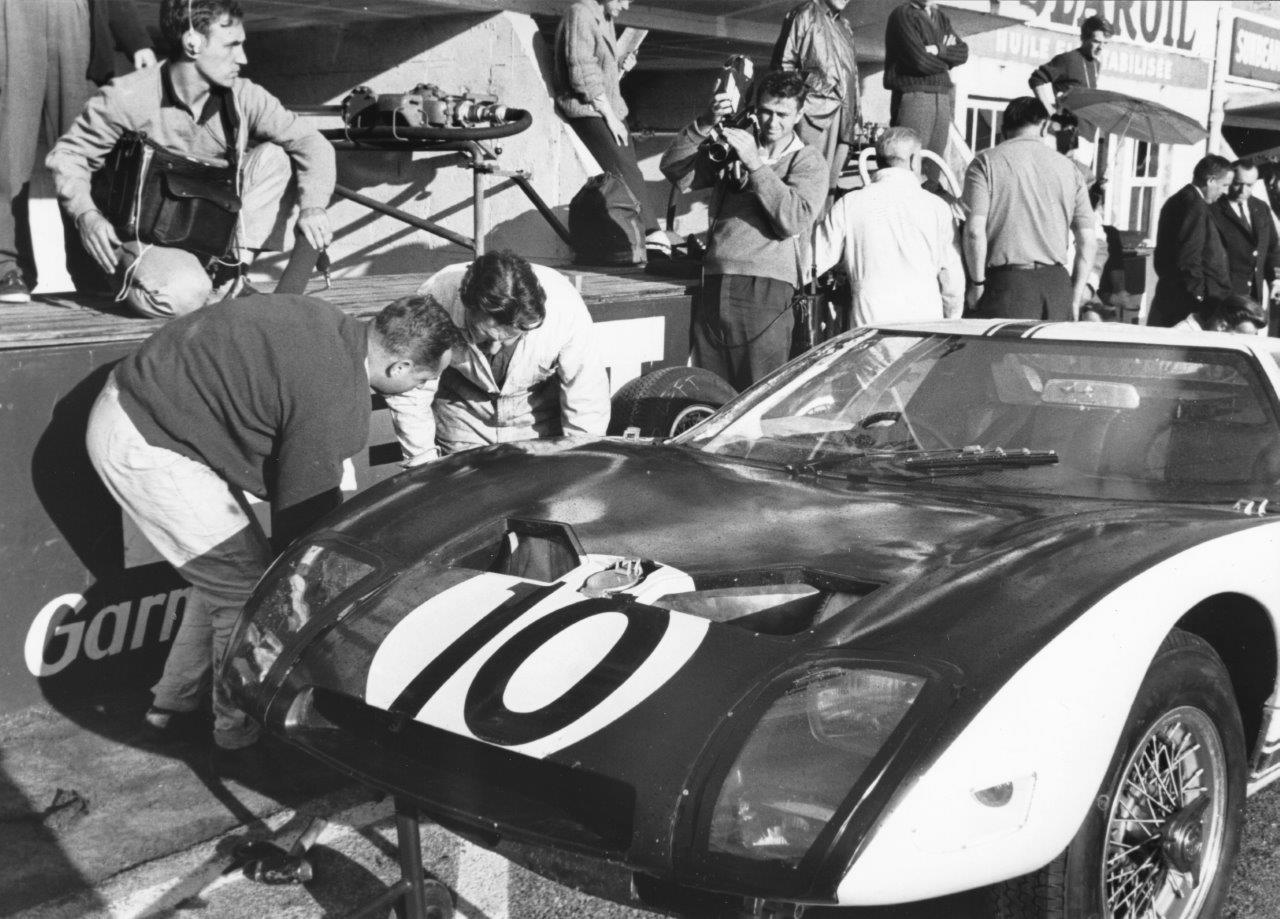

By late 1963 a two-thirds scale model had been made in Dearborn for wind-tunnel tests where air-flow was limited to 120mph, far lower than speeds achieved at Le Mans. During March 1964, Abbey Panels of Coventry delivered the first monocoque chassis. As the April date for the Le Mans Trials approached, GT/101 had to be completed within two weeks. The experienced team manager, John Wyer, was concerned that insufficient time was available to test the car properly before its first public appearance so he was not amused when Ford demanded the prototype be flown overnight to New York to be put on display at a Motor Show and revealed to the world’s press. It returned to the UK within 24 hours but it was time lost.

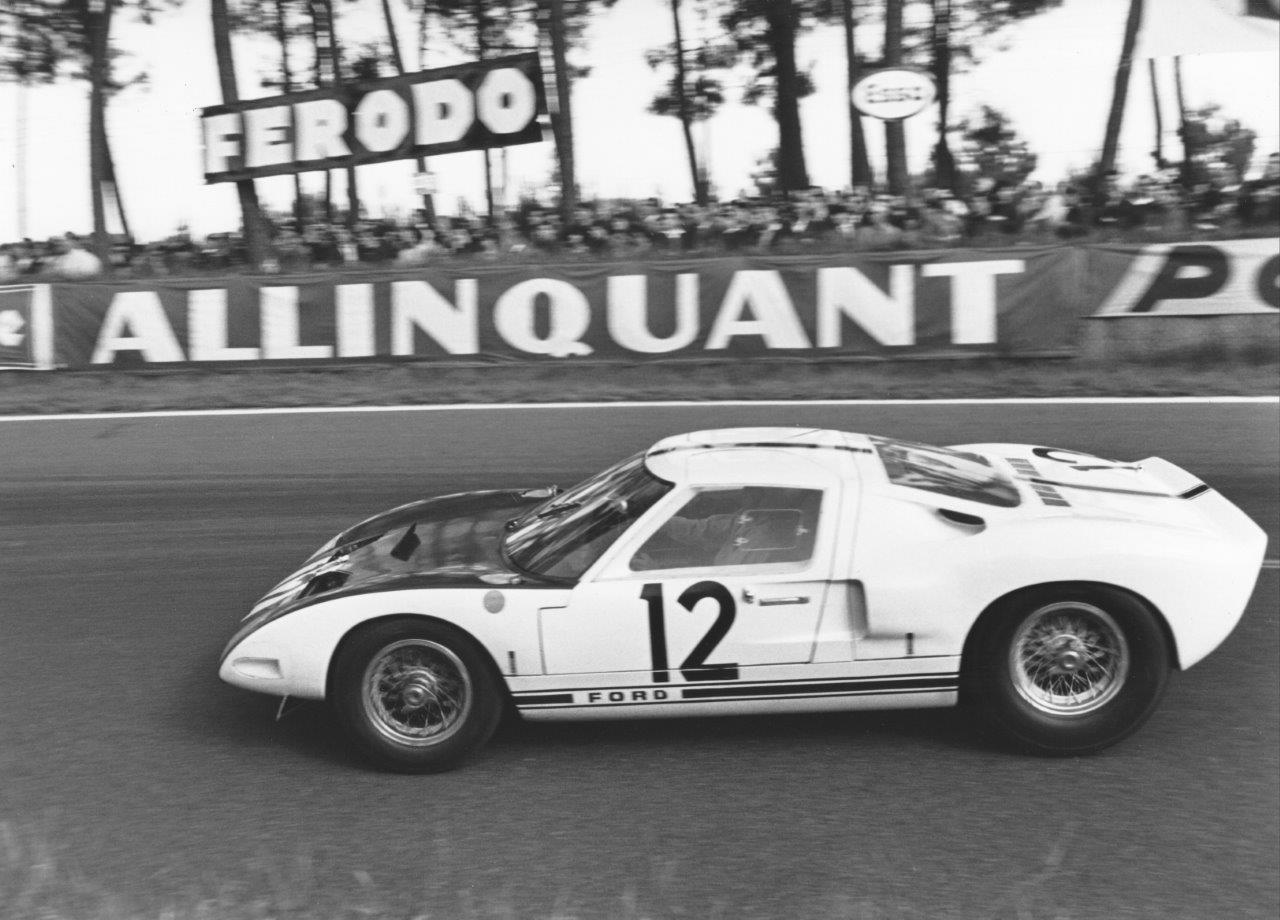

Ford GT/101 was joined by the second car (102) at the Le Mans Speed Trials where the elegant (almost pretty) new GTs suffered from a serious lack of downforce as the drivers experienced tail lift; the wind tunnel tests had compromised the design. The cars were virtually undriveable and left the circuit with GT/101 being destroyed when Jo Schlesser lost control at high speed. With one car written off and the other damaged, a lot of work was required to complete the third and fourth GTs and cure the downforce problem. When the three woefully unprepared Ford GTs arrived at Le Mans, they looked different with a wide hole across the nose and driving lights incoporated within a larger headlamp cluster.

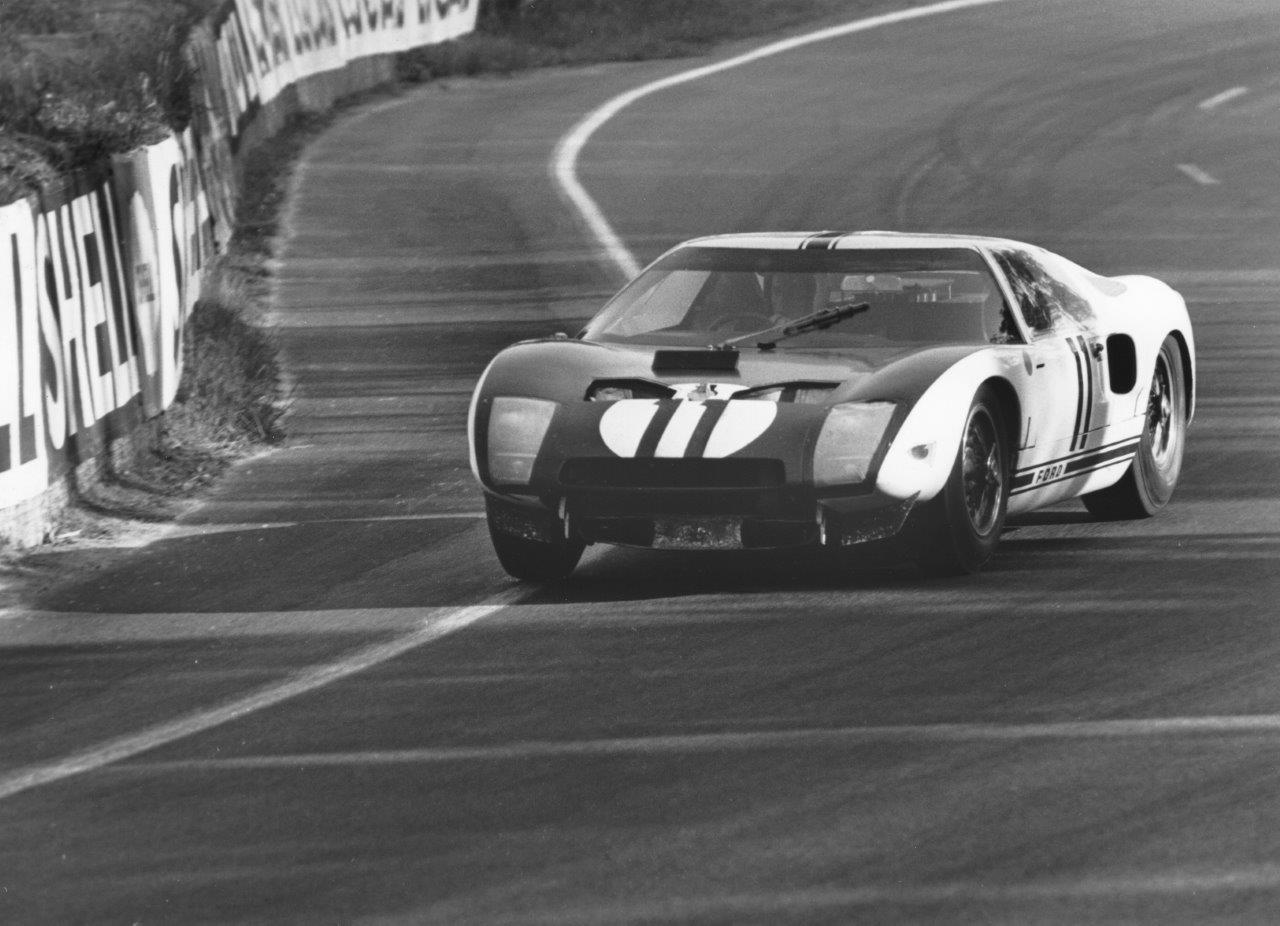

There was some reason for optimism during practice as the Fords matched the pace of the Ferraris. GT/103 was second on the grid driven by Richie Ginther/Masten Gregory with the other GTs not far behind. The Fords did not start well; Phil Hill’s GT/102 took a long time to start and was dropped to 44th place but Ginther was determined to put on a show and moved into the lead by the end of the first lap. However, a slow fuel stop cost him the lead. The Fords continued to chase the Ferraris before, in the early evening, problems arose. GT/104 caught fire and was extensively damaged and shortly after, GT/103 retired with transmission failure. Phil Hill and Bruce McLaren had made steady progress to lie in fourth place but in the early hours of Sunday morning the strain on the transmission proved too much and Ford’s race was over. The Colotti gearboxes were unable to cope with the demand put upon them but there were no suitable alternatives until, in 1965, ZF produced a ‘box strong enough to cope with the torque of the Ford V8 engine. The motoring press poured scorn on the expensive project that originated in a wind tunnel, only to suffer obvious aerodynamic problems. The solution was to add a small metal strip across the tail to create the necessary downforce, allowing the drivers to take full advantage of a top speed of around 200mph.

Due to pressure to succeed, Ford Advanced Vehicles had little option but to continue entering races until the next Le Mans 24 Hour endurance race, all the while developing the car in public and suffering the inevitable publicity when things went wrong, as they so often did. In the USA, Ford handed responsibility for the GT40 project to Shelby American with a clear instruction to turn the car into a winner, something that had eluded it since it was launched. Shelby decided the way to win Le Mans was to make use of a big-block V8 that could run for hours at low revs and less stress. When the GT40s arrive at Le Mans in 1965, two of the six entries were powered by 7-litre, 427cu.in V8s and were renamed the MkII. One of the cars was so new it had yet to turn a wheel. FAV entered one 289-powered GT40 for its final race as an official Ford entrant before concentrating on building the 50 examples required to qualify the GT40 as a production sports car.

Despite having replaced the Colotti transmission, reliability issues continued to disrupt the GT project. The use of a stronger gearbox revealed problems with the 289 engines which had not been built to the correct specifications by Ford’s foundry. In spite of a strong initial showing during the first few hours of Le Mans 1965, allowing Ford a glimmer of hope, the cars gradually departed the race with mix of engine and gearbox problems. It was a race of attrition for all the teams and Ferrari only secured victory thanks to a private entrant. The final tally showed all Ford-powered cars bar one as ‘Did Not Finish’. It was left to those in charge of the project to return to the USA to explain to Henry Ford II why his millions of dollars had not bought him the victory he demanded; as history recalls, the GT40 programme was allowed one final chance. 1966 had to be a success – or else.