Coldplay bassist and Porsche collector Guy Berryman shares his devotion to detail, authenticity and the all-important human angle.

After almost 25 years on bass in one of the most popular and prolific rock bands of all time, Guy Berryman is best known to millions as one quarter of Coldplay. But away from the music industry’s frontline, Berryman has been nurturing other passions, becoming a respected collector and restorer of classic sports cars and more recently creative director of ‘The Road Rat’, a widely admired automotive quarterly.

In truth, his love of cars has been a formative and lifelong influence. As a child growing up in Scotland in the 1980s, the styling of his father’s mothballed Triumph TR3A shone a light on a bygone era of design and engineering. Young Berryman was frequently found behind the TR’s wheel, transported to another world amid cobwebs and boxes of mysterious parts. A seed was sown.

Prior to the all-consuming rise of Coldplay, Berryman had begun studying mechanical engineering at University College London. As he explains during a tour of the garages at his home in the Cotswolds, this remains a vital part of his approach to, and appreciation of, the automotive world.

“My interest in cars fundamentally lies with the engineering and concepts behind them,” he says. “All of the cars in my collection have something significant beneath the surface. I’m a great believer in the idea of form following function, and it’s something that works for me across a range of different fields. Whether its industrial design, clothing or cars, if you follow that mantra you always end up with real purity.”

When it comes to cars, Berryman’s preferences lean heavily towards the past, evidenced by a collection rich in mid-20th century European exotica. “I think there was a design language in the 1950s and 60s that had a very beautiful, sculptural quality to it as a result of things being drawn by hand. Back in the 60s I think there was a real flamboyance, spirit and energy in automotive design that resulted in these very pure forms.”

Berryman’s passion for the subject reaches far beyond the mere aesthetic however. Setting him apart from most contemporary collectors, the 42-year-old is heavily involved in the restoration of his cars and has an extensive workshop at home where numerous projects can be found in various states of repair. “My interest in being hands-on, in pulling cars apart and rebuilding them, has an obvious connection to my past in mechanical engineering. I’m fascinated by learning, deconstructing – I think everything I do in life creatively involves looking at an object and deconstructing it, either mentally or physically. It’s how my brain works.”

“I go to great lengths to restore cars in a way that is true to how they would have left the factory.”

(Guy Berryman)

What sets Berryman’s process apart is an almost reverential attention to detail; something that often takes him deep into a car’s past. He has spent years unravelling lost histories, contacting previous owners and delving into archives. “I go to great lengths to restore cars in a way that is true to how they would have left the factory – replicating materials, finishes and colours – often details you would never see, such as inside a panel or door. Anything that is found during disassembly has to be preserved or recreated when the car is put back together.”

This fascination with processes and detail was a driving force by the ‘The Road Rat’. Set up by Berryman and his partners in the project, Mikey Harvey and Jon Claydon, it is a magazine that celebrates print media, long form journalism and traditional production methods just as much as cars themselves.

“We wanted editorial depth,” Berryman explains, “and to tell stories in an authoritative way that always introduces the human element. It’s not just a car, in other words. Why is it there? Who made it? What are the real stories behind it?”

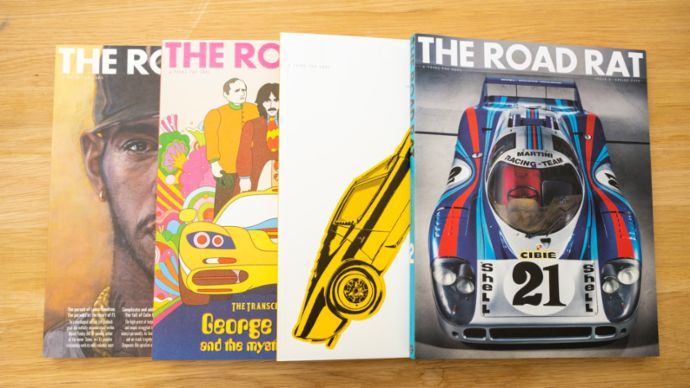

The perfect example arrived in issue two, with the Martini Racing 917 Langheck consuming the cover. The accompanying piece ran to almost 8,000 words, illustrated with previously unseen archive imagery from Zuffenhausen and detailed technical drawings. It focussed not on the 917’s racing prowess but instead on the extraordinary journey from inception to homologation in the spring of 1969; the tensions, the politics, the visionary engineers. And barely a wheel turned in anger.

With quite so many irons in the fire, it’s surprising that anything gets driven, but that would be to underestimate Berryman’s devotion to the road. A regular pan-European tourer, he owns no fewer than five classic Porsche models, each underscoring his appreciation of the marque’s rich history and engineering integrity.

An immaculately restored 1967 911S shares garage space with a 914/6 converted to GT specification and a totally original 911 from 1968 that once belonged to Porsche modifier and founder of Rennenhaus, Clay Grady. Grady’s battle-worn 914 racer is also in Berryman’s possession, as is an ultra-rare 356 Zagato, one of nine continuation cars built to the drawings of the little-known one-off 1958 racer.

“It’s a great car,” Berryman says. “It’s light as a feather and so open. And it’s the car that has given me the greatest road trip of my life so far. I picked it up from Zagato in Milan with my friend Magne Furuholmen from A-ha and drove it up through the lakes, across to Chamonix and all the way down the Alps to Nice. We drove through the most inclement weather you could possibly imagine. There were lightning storms and visibility was down to about four metres on these twisty alpine roads. People in modern cars had decided it was unsafe to carry on but we had to get to Nice by a certain time so we ploughed on in these bright yellow raincoats with the car filling up with water. Each night when we got to the hotel we’d have to ask for a bucket to scoop the water out of the car.”

It’s another example of Berryman’s absolute commitment to the cause, from exacting ground-up restorations to driving his cars as their manufacturers intended; an increasingly rare trait today.

“I don’t think people drive their cars enough,” he says, “which is a shame from a personal and cultural point of view. When there really is a full stop on the combustion age we’ll see classic cars in context and appreciate them all the more. The move to electrification day-to-day is great, and the Taycan is definitely on my radar as a daily driver, but whenever I drive down the street in a classic car, it only ever generates smiles. The lives these cars have led. The stories they can tell. They’re irreplaceable.”

Report by Porsche.com (first published by newsroom.porsche.com)