Building cars is a pretty global affair these days. Everybody seems to have a factory everywhere, and even tiny specialist automakers source major components from overseas. Sixty years ago, it wasn’t as common to find the best of the Old World mixed with the best of the New, but it did happen, usually in the form of a European chassis and body powered by a pushrod V-8 from somewhere in Michigan.

British Bristols, French Facel Vegas, and Italian DeTomasos all enjoyed the unbeaten bang-for-your-buck of an American V-8, but the prettiest Euro/American hybrid has to be a low, slippery Chevy-powered coupe built in Tuscany for a few very short years in the ’60s—the Bizzarrini 5300. Aside from some versions of the Cobra, it’s also the most valuable.

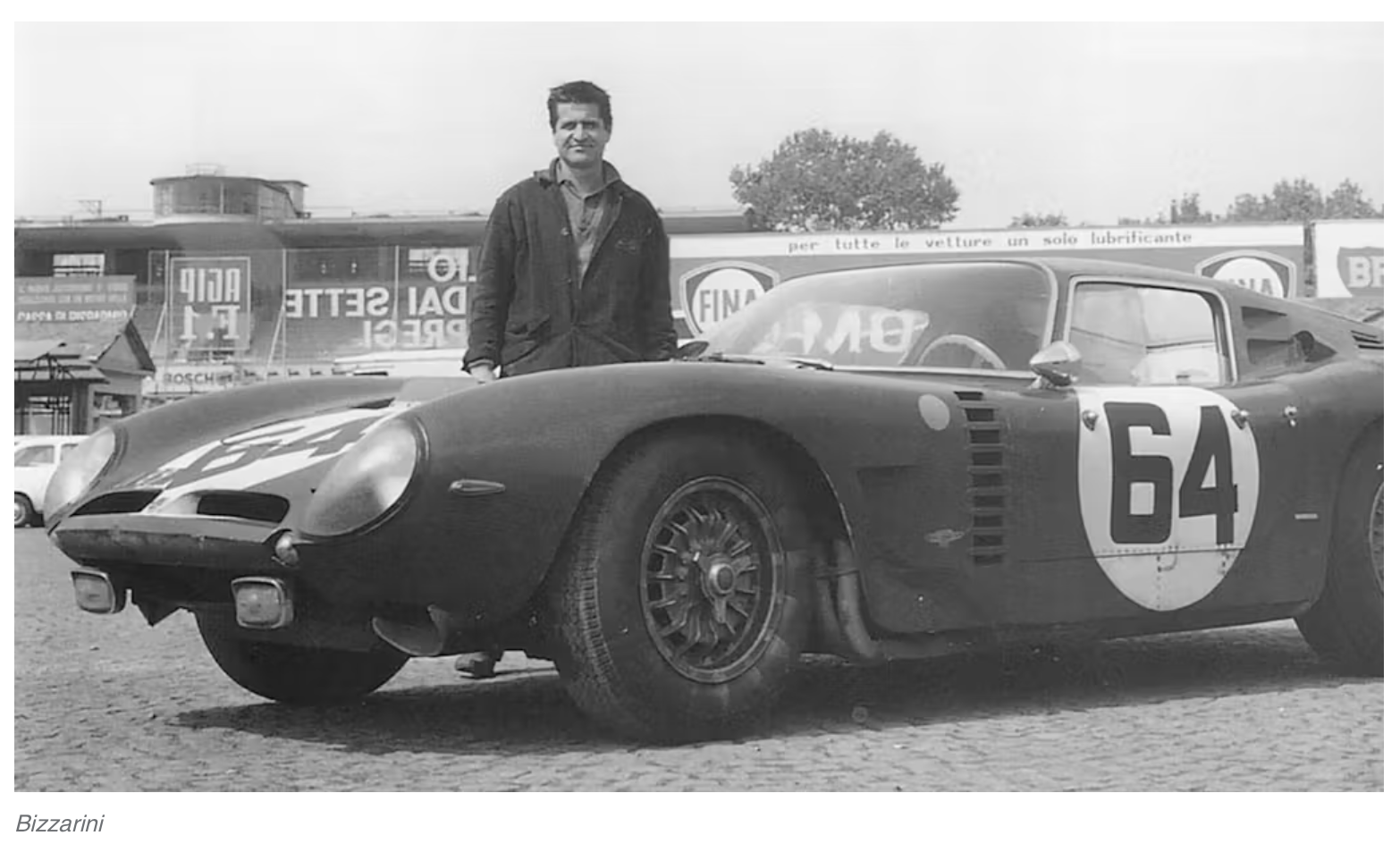

Giotto Bizzarrini

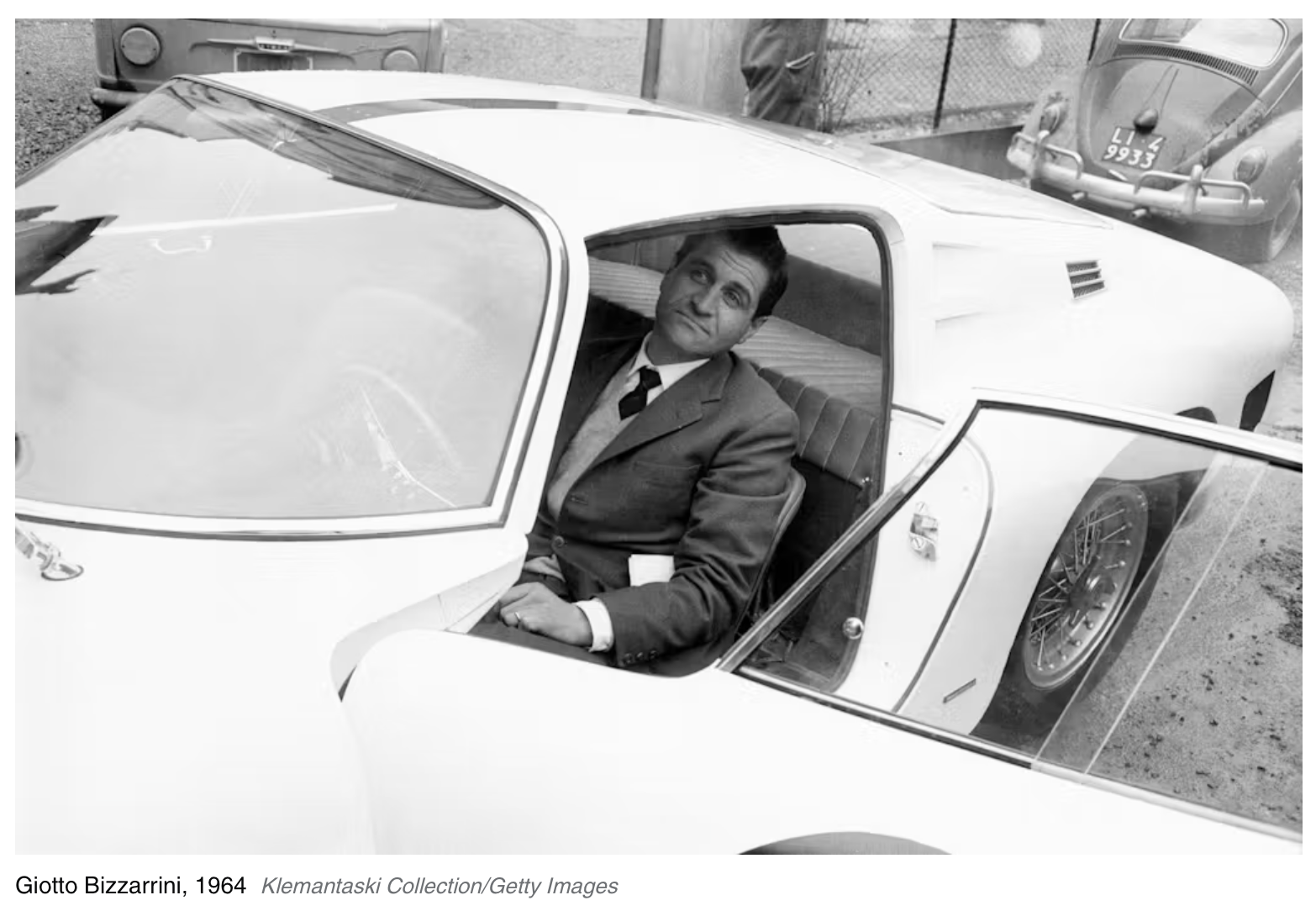

With a small, boutique manufacturer, it’s omitting a lot to examine the cars but ignore the person behind them. This is especially true of Giotto Bizzarrini, and building cars bearing his own name was just one chapter in an impressively long, far-reaching career in the car business.

Bizzarrini was born in 1926 in a town near Livorno on Italy’s northwest coast. His was a family of engineers, so his chosen career path was no surprise, and in 1953 he received a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Pisa. For his senior thesis, he modified an old Fiat Topolino with new bodywork, moved the engine farther back in the chassis, and tuned the engine. A job at Alfa Romeo followed, and a job at Ferrari followed that (he drove his custom Fiat to the interview). Technically, Ferrari hired on Bizzarrini as a test driver, but his background as an engineer was a big advantage—“Typically a test driver would find the problem, then call an engineer who fixed it … Conversely, an engineer had to use a test driver to find the problem, then test the solution. I could do everything, from start to finish.”*

By the end of the decade, he was the boss of Ferrari’s Experimental, Sport and GT Car Development department. Ferrari put out many of its all-time greats in the late ’50s and early ’60s, and Bizzarrini contributed to the 250 Testa Rossa, 250 GT SWB, and 250 GT California. The climax of his work in Modena were contributions to the 250 GTO, including tweaks to the rear suspension with coil springs over tube shocks, and moving the drivetrain farther back and lower down to allow for a sharper, more aerodynamic nose.

The GTO, of course, went on to do great things, but before it was done, Bizzarrini got caught up in bitter internal politics, in large part thanks to Enzo Ferrari’s wife taking a more active role in the company. Within a few days in October of 1961, Bizzarrini and several other higher-ups at Ferrari (which naturally included talented engineers and designers) either quit or were fired by Enzo, in what’s often referred to as the “palace revolt” or Ferrari’s “night of the long knives,” a reference to the German political purge of the 1930s.

Quickly, the exiled group found wealthy backers and formed a new company called ATS (Automobili Turismo e Sport) with the aim of beating Ferrari at its own game on both road and track. By 1963, they were ready with their first model—the mid-engined ATS 2500 GT. The car was rather advanced and undeniably gorgeous, but there was a clash of personalities at this company, too, and the project quickly fell apart. Bizzarrini became a hired gun, having already started his own design and engineering firm called Società Autostar in Livorno 1962.

One of his jobs as a free agent was creating the famous Ferrari 250 GT “Breadvan.” The background of this odd-looking but effective racer was that Count Giovanni Volpi had ordered a couple of 250 GTOs from Ferrari. He later recalled that Enzo rung him up on the phone and “told me to forget it.” Why? Volpi was bankrolling the ex-Ferrari apostates at ATS. So he bought a 250 GT SWB (the GTO’s predecessor) and hired Bizzarrini to make a GTO-beater. The Breadvan had mixed success in period, but it’s had an active life in historic racing, particularly at the Goodwood Revival.

Bizzarrini also worked with another Italian automotive acronym—ASA (Autocostruzioni Società per Azioni). This Milanese firm had purchased the rights to build the so-called Ferrarina, a small sports car powered by a Ferrari-designed 1032cc, 91-hp four-cylinder, essentially one-third of a Ferrari 250 V-12 engine. Before Ferrari had sold the rights to the car and before Bizzarrini had left Ferrari, he had worked on the project, so he was familiar. Like ATS, though, ASA was a short-lived concern, and only built around 100 cars.

In 1963, Bizzarrini went to work for another upstart that had beef with Ferrari—Lamborghini. The tractor maker turned car manufacturer hired him to design its new flagship engine, a 3.5-liter V-12 with a target output of 350 horsepower. The basic layout of the Bizzarrini-designed Lamborghini V-12 lasted all the way up until 2010.

Iso

After Ferruccio Lamborghini came Renzo Rivolta. His firm, Iso, had built scooters, motorcycles, and the original Isetta microcar in the 1950s, but he also sensed a growing demand for an expensive GT car that wasn’t as temperamental as those coming out of 1960s England and Italy. One promising car Rivolta looked at was the upcoming British-built, Italian-styled, American-powered Gordon-Keeble. He wanted to build something similar, but after Bizzarrini tested a Gordon-Keeble, he reportedly concluded: “The car cannot compete with a Ferrari … Throw away everything but the engine and the De Dion rear axle.” And so the new car, called the Iso Rivolta GT, would have a De Dion axle and a 327-cubic-inch V-8 lifted from the Corvette, but Bizzarrini designed a pressed steel platform chassis from scratch, welded to a 2+2 coupe body penned by a young Giorgetto Giugiaro at Bertone. “It is the car we have all been looking for,” gushed Road & Track.

The four-seater done, Bizzarrini and Rivolta next set about building a two-seater, based on a shortened Iso Rivolta chassis, also bodied by Bertone, and called the Iso Grifo. Bizzarrini hounded Rivolta to go racing, but the latter showed no interest. Then, “[w]hen my consulting contract with Iso ended Rivolta gave me a rolling chassis and said: ‘now you can go make the competition car yourself,’” though the two firms maintained a close working relationship.

Bizzarrini then “started with the idea of the Ferrari GTO and wanted to improve on it.” He shortened the wheelbase and moved the Weber-carbureted Chevy engine even farther back in the chassis. Giugiaro penned a low-slung body and Piero Drogo in Modena built it in aluminum. The whole car was barely ready for the Turin Auto Show in late 1963, with not even enough time to paint it, but it graced the Iso stand in bare aluminum, along with an Iso Rivolta and the new Grifo A3/L (Lusso or “Luxury”). Called the Iso Grifo A3/C (Corsa or “Race”), it was a hit at the Turin show. The first one sold, and an American racer put in an order for the second. Bizzarrini was Italy’s newest carmaker, and in the first half of 1964, he changed the name of his shop from Autostar to Prototipi Bizzarrini S.r.l. (it became Bizzarrini S.p.A. a couple of years later).

Bizzarrini finished a car in time to send it to the 12 Hours of Sebring in March. Transmission issues doomed it to a dismal 39th overall finish, but it showed promise, hitting 157 mph on the main straight and garnering some good press. Sports Car Graphic covered the effort and called the Iso Grifo A3/C a “cross between a Sting Ray Corvette and a Ferrari GTO.” Then, at the Nürburgring, Bizzarrini entered a lone Grifo A3/C that finished 19th overall but second in class. At Le Mans, the team’s red Grifo hit over 170 on the Mulsanne straight and mostly ran very well, but a brake issue relegated it to 14th overall and fourth in class. After a few more mediocre results, one car finished second overall in Iso’s backyard at Monza.

The 1965 race season didn’t start off any better—In fact, it was much worse. Bizzarrini fielded two cars at Sebring. One crashed after its brakes failed in the first hour. Later in the day, after torrential rain started, the other one lost control and spun into a pedestrian bridge, splitting in half. What’s worse, Iso’s West Coast importer had flown out in his private plane to watch the race and was enthusiastic about potentially bringing more of Iso and Bizzarrini’s cars to America, but his plane crashed and killed him on the way home. At Le Mans, however, one of the Grifo A3/Cs finished ninth overall and first in class, which would be the highlight of the car’s racing career.

Despite the so-so record on track, Bizzarrini’s racier version of the Grifo was promising enough and gorgeous enough that people started asking for a road-going version. He obliged with the A3 Stradale (“Street”), which added road car accoutrements like leather, carpets, an upholstered transmission tunnel, roll-up windows, and a heater. The engine was a 365-hp version of the Chevrolet V-8, now fed by a four-barrel carburetor instead of the Webers of the race car. British magazine Autosport tested one of the Stradales, and got it to hit 171 mph. Writer John Bolster called it “the most beautiful car ever tested by Autosport” and went on to proclaim that “to drive the Grifo is a splendid experience … The Iso is a very stable car, tending to understeer unless a good deal of power is applied. It corners fast with virtually no roll for the suspension is definitely hard, but not objectionably so.”

Setting off on his own

Soon, another clash of personalities between Giotto Bizzarrini and Renzo Rivolta saw the pair split in the summer of ’65. Iso would continue to supply Bizzarrini with parts and continued to build the plusher, more conservatively styled Iso Grifo GL on its own. Bizzarrini also produced a handful of cars badged as “Bizzarrini Grifo 5300” before ceding the use of the Grifo name and calling his own cars “Bizzarrini GT Strada 5300” instead.

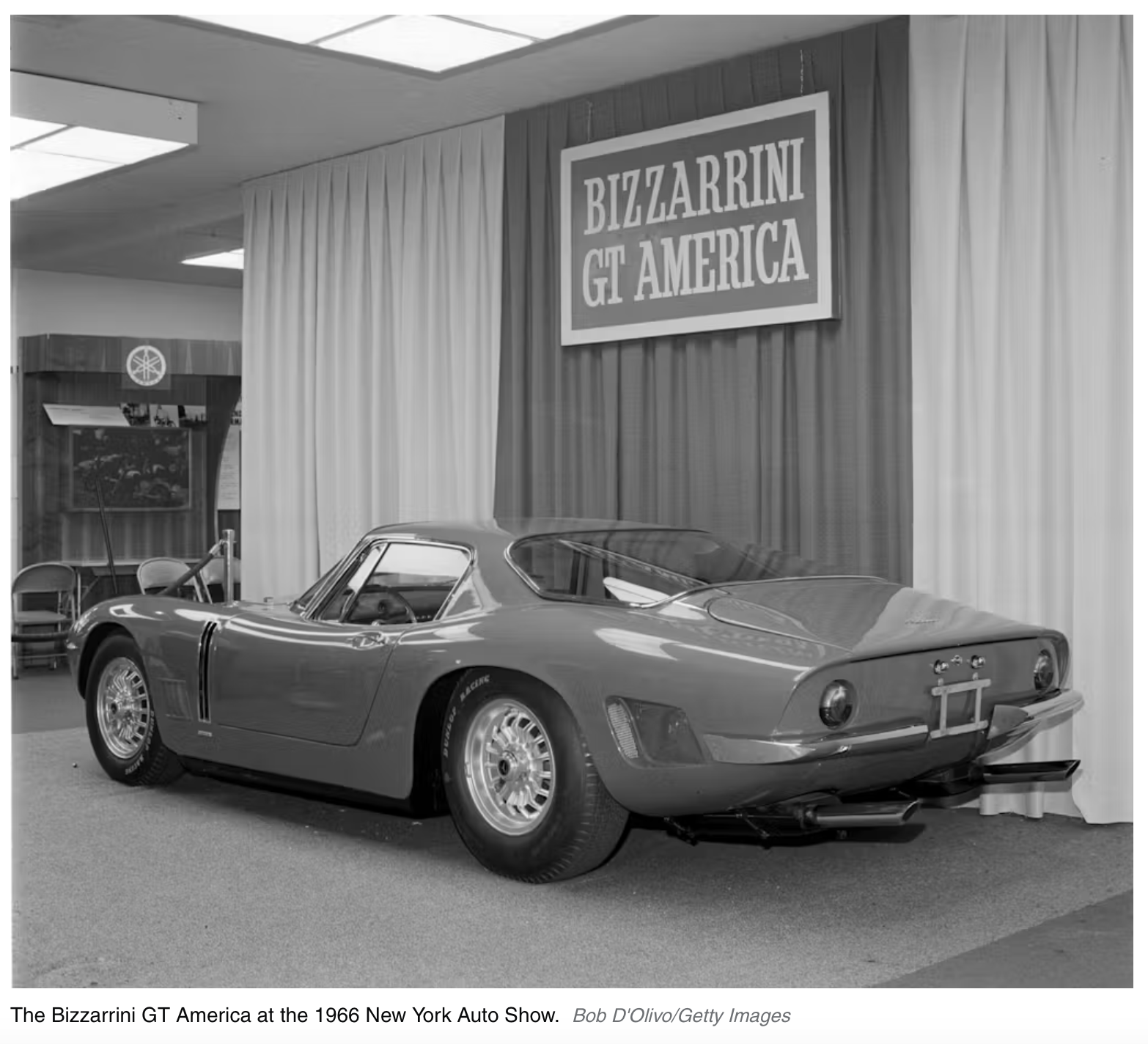

In early 1966, Bizzarrini then added the “GT America” to his limited lineup. It looked identical to the Strada, but the America came with a fiberglass body and independent rear suspension via unequal-length A-arms, coil springs, and tube shocks instead of a De Dion rear. In the U.S. this new America model cost about $10,500, well over $4000 less than Ferrari’s 275 GTB/4 and not much more than half as much as the new Lamborghini Miura. Road & Track loved its looks, claiming “we rate the Bizzarrini as one of the cars we’d most like to be seen in, and it was a pleasure to look up to the Jaguar XKE.” The magazine also called it “closer than anything we’ve driven to the contemporary racing machine” and put it on the cover of its December 1966 issue.

Every period magazine tester came away impressed with the Bizzarrini’s performance, but not everybody was so effusive. Sports Car Graphic critiqued the hard seats, an “apparently insane” fuel gauge, and that since the engine was so far back and so close to the firewall, the distributor sometimes knocked against it, and getting to the distributor required a removable cover on top of the dash (“not an ideal way to spend a Wednesday evening.”) “Some cars are brutes—if your wife enjoys driving this one, her name is George,” the test concluded.

Car and Driver, meanwhile, praised the Bizzarrini’s bold looks despite the design being a few years old and for the whole concept of an exotic-looking Italian car with reliable Corvette power being “much better suited to America than a Ferrari and at a much lower price.” At the same time, the magazine noted its “startling shortcomings of convenience and accessibility”, like shoddy fiberglass work, heavy steering, and low ground clearance.

Bizzarrini was selling his 5300 models as fast as he could build them (which wasn’t very fast), but he also set to work on a similarly styled but scaled-down and lower-priced version with wider, middle-class appeal. By late 1965 he had a prototype square tube chassis and body buck completed. A 1500cc Fiat four-cylinder and ZF five-speed were later hooked up along with independent front and De Dion rear suspension, and a fiberglass body, which successfully packed the 5300’s graceful proportions into a smaller package, laid on top. The production version, however, used a 1.9-liter four-cylinder from Opel. Bizzarrini named it the “1900 GT Europa,” and it debuted at the Turin show in 1966. “It has all the merits for excellent success,” quipped Italian magazine Quattroruote.

Things looked like they were going right for Bizzarrini, then, but they soon started going very wrong. Always drawn to racing, he continued competing with the 5300 while designing and developing a mid-engine racer called the P538 (Posteriore for mid-engine, 5.3 liters, 8 cylinders). A proper prototype that shared both styling cues and engines with the road cars, it could potentially compete for overall wins while promoting Bizzarrini’s business. Unfortunately, the P538 didn’t do much. It was a DNF at Le Mans in 1966, didn’t pass technical inspection there in 1967, and had mixed results elsewhere. Then, after Bizzarrini had dumped tons of money into this effort (“all my financial resources at that time,” he claimed), a rules change for the 1968 season limited low-volume prototypes like the P538 to a 3.0-liter displacement, effectively ending the car’s career.

Meanwhile, the company just wasn’t building road cars quickly enough. In 1967, three investors injected much-needed capital, and Bizzarrini was able to contract with a small coachbuilder to make bodies. About two months later, though, the coachbuilder declared bankruptcy, and Bizzarrini took body production in-house. Despite that setback, Bizzarrini was working on new models, including a 2+2, a 5300 Spyder, and the Giugiaro-styled mid-engined Manta.

The worst news came in the summer of 1968 when Bizzarrini got a phone call from the bank, informing him there was no money in his account. Focused on the production side of the business, he had let his new investors handle the records and bookkeeping. Several times, two of them had used the company’s value to borrow money against their holdings, then brought in unsuspecting new investors to buy shares that covered the loans.

The Ponzi scheme effectively killed Bizzarrini the company, and financially ruined Bizzarrini the man. He lost his apartment in Livorno and a farm in the countryside. “I am a pure technician who knows nothing about business. In the end I fell to two Al Capones. And that was the end of the story”, he said.

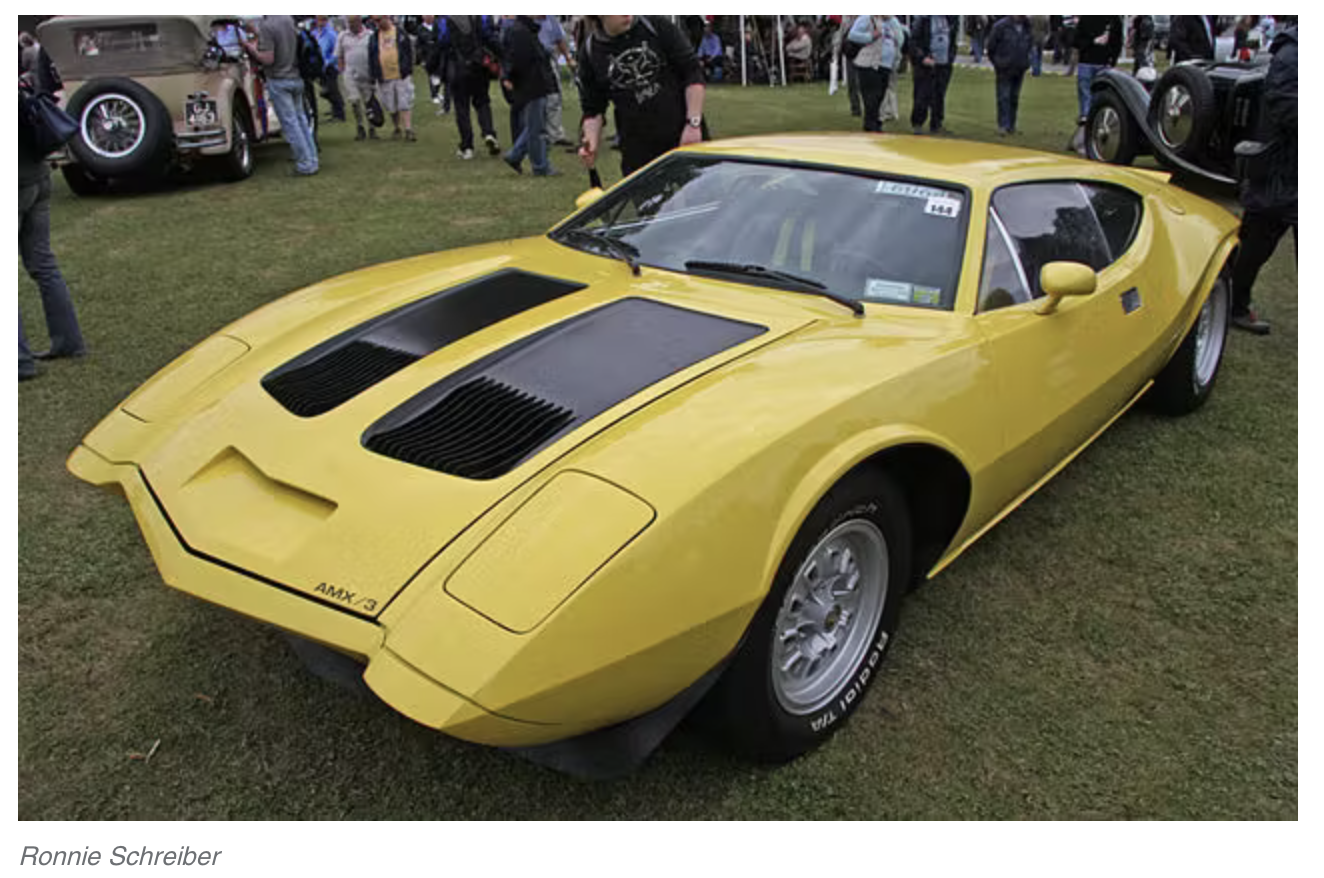

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Bizzarrini soon worked on the exciting mid-engine AMC AMX/3, and started a workshop called Laboratorio Automotori Bizzarrini. His old friends at Iso hired him to work on the Lele. Later, he taught at the University of Florence, worked with Kawasaki on four-valve heads and a lightweight chassis for the Japanese company’s motorcycles, and regularly repaired examples of his old Bizzarrini road cars for customers. Oh, and he made wine, too.

In the ’80s, he worked with a group of investors on a potential Formula One car for the 1989 season, but that went nowhere. In the early ’90s, with backing from a wealthy Californian, he built up a prototype supercar using a crashed Ferrari Testarossa chassis and carbon fiber bodywork. The production version might have used Corvette ZR-1 power, but the collaboration went nowhere, either, thanks to a tough global economy. Then, for a group of Italian investors, he designed a new Lancia-powered supercar called the Picchio, but this car didn’t progress past the prototype stage. He worked with Pininfarina on its 1996 Eta Beta concept city car and was working well into the 2000s. He passed away in 2023, aged 96.

The market

Bizzarrini’s talents touched a lot of cars, but the ones bearing his name are quite rare. There were seven Iso Grifo A3/Cs, 16 Iso Grifo A3 Stradales, approximately 115 Bizzarrini Grifo/Strada 5300/GT Americas, approximately 10 Bizzarrini Corsa/Competiziones, and about a dozen GT Europa 1900s, plus a handful of specials and one-offs. From 2022-24, a revived Bizzarrini band built and sold a total of 24 “Revival Edition” models, “envisioned as a reintroduction of the Bizzarrini brand to the elite tiers of the automotive world.” A continuation car, in other words, reportedly built using original blueprints, original suppliers, and input from people involved in the original project. Each one was built to the same specs as the car that finished ninth at Le Mans in ’65, and cost roughly $2M.

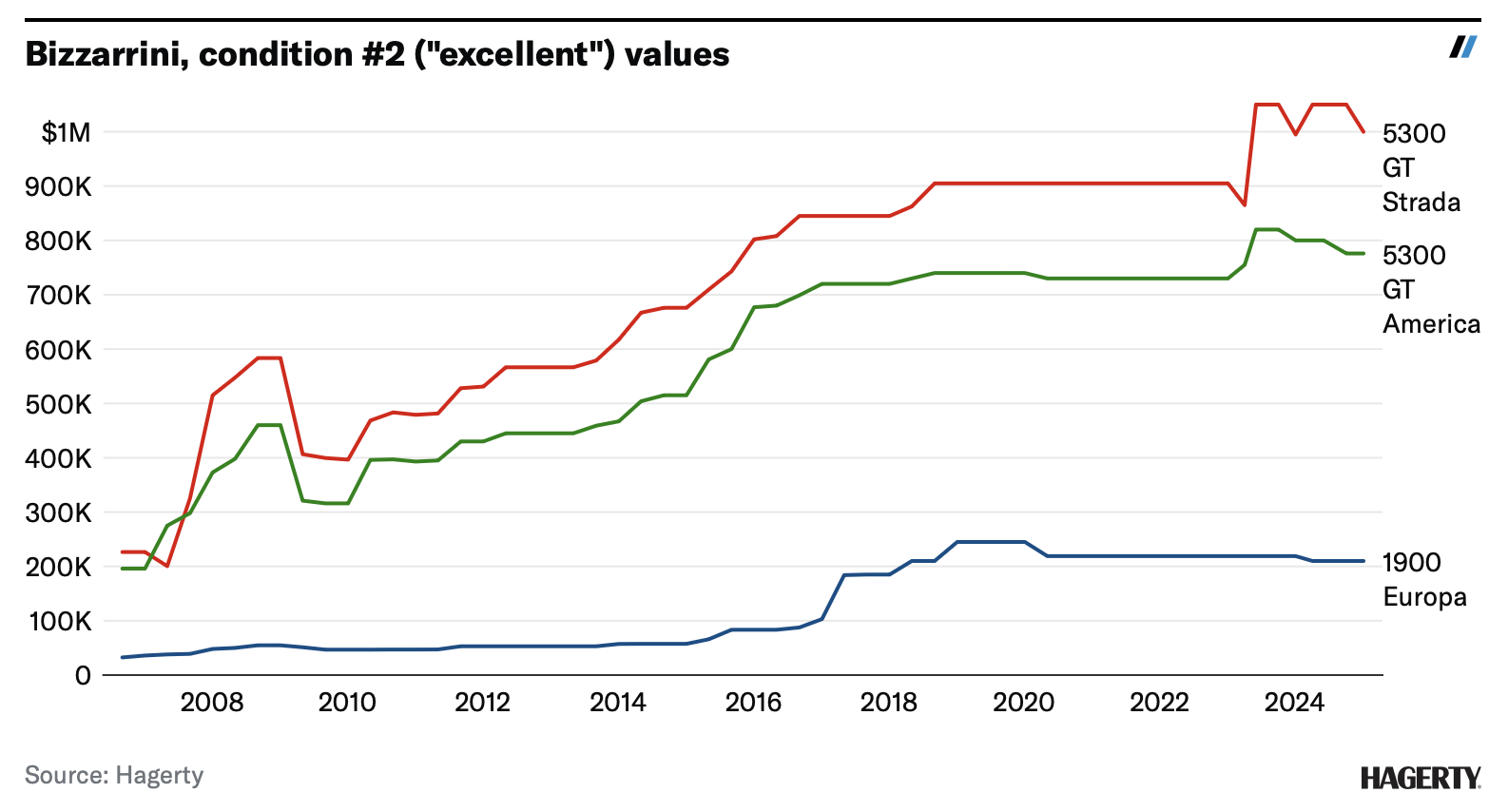

Today, the Hagerty Price Guide values the most common Bizzarrini road cars—the 5300 Strada, the GT America, and the 1900 GT Europa. The condition #2 (“excellent”) value for an alloy-bodied 5300 Strada comes in at an even $1M. The fiberglass-bodied GT America comes in at a cheaper but still very expensive $776,000 in the same condition, and the four-cylinder Europa at $204,000.

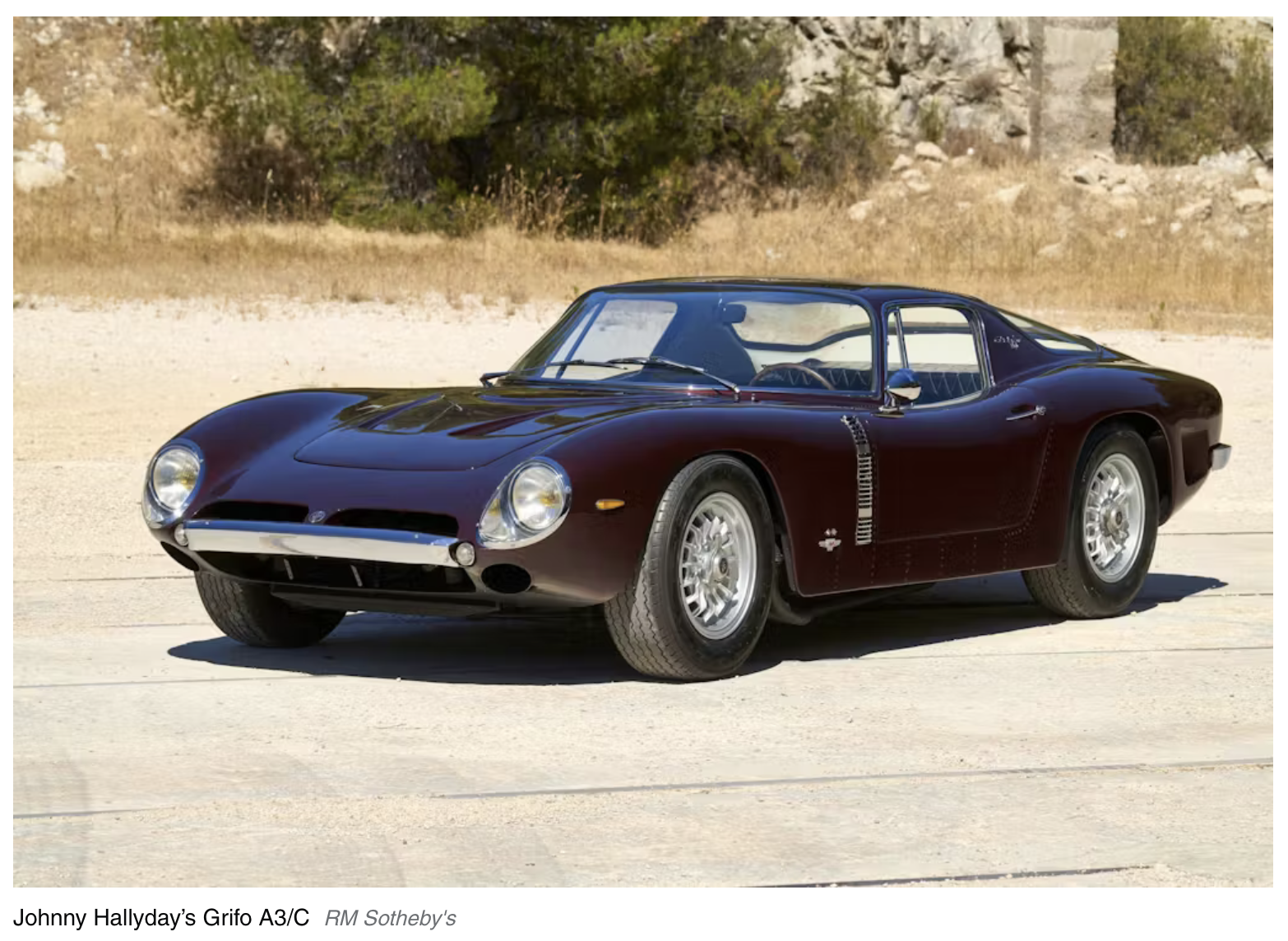

The most expensive Bizzarrini ever sold at auction is one of the Grifo A3/Cs made before his split with Iso. Bought new by singer Johnny Hallyday (aka “the Elvis Presley of France”), it brought €1,805,000 ($2,042,899) in 2021. The first one to sell for seven figures was a €1,244,400 ($1,409,905) result for a 5300 Strada in Paris in 2015. Bizzarrinis only appear at auction once every year or two, but the last 5300 Strada to sell at auction brought €736,250 ($793,162) in Monaco last year, while the last Europa seen at auction brought $147,500 a month later.

Unlike some other European sports cars with corporate American V-8 hearts, a Bizzarrini isn’t really a bargain next to its thoroughbred peers. But, given their drop-dead sexy looks, their performance, their rarity, their racing DNA, and the rich history of the man who built them, it’s easy to see why they’re so highly regarded by the market today.

*Quotes from Bizzarrini and the production figures for his cars come from the 2004 book Bizzarrini: A technician devoted to motor-racing, by Winston Goodfellow.

Report by Andrew Newton for hagerty.com