You would think breaking into the Formula One world during the 1970s as a photographer would be a pretty tall order for most 18-year-olds. But for Grand Prix Classics Founder and Owner, Mark Leonard, he found a way in quite literally – through a hole in the fence.

His is a story about exposure

From his late father, Max Leonard’s fervent passion for fast sportscars and photography, it was only fitting that he took Mark and his older brother, Michael to the great Grand Prix venues across Europe throughout their childhoods. Exposing them to Silverstone and Monaco, depth of field and aperture, Max Leonard set the stage for his sons’ insatiable appetite for Formula One, and their later appreciation of the sport’s unforgettable era of the 1970s.

All they needed was a Volkswagen camper bus.

“It was Michael’s idea,” explains Mark as he fondly reminisces how his brother at 20, also a talented photographer, caught onto the idea of borrowing their father’s VW camper bus as a way for the two of them to attend the F1 races. Equipped with their Nikon FT Motor Drive cameras, their first stop was the Dutch Grand Prix in July 1973 at the Zandvoort Circuit in the Netherlands. As captivated spectators behind the fence, no one would have predicted the horrific event that Michael would happen to shoot: a sequence of 8 haunting photos that showed frame-by-frame, Roger Williamson’s fatal crash. With the motor drive (that allowed 5 frames per second), the moment is eerily relived. Williamson’s car quickly engulfed in flames, it was a tragedy that not only shook the racing world, but shone a light on the total deficit of safety culture at the time. With a race that still went on despite the crash, and no fire trucks immediately on the scene, it was a quite unforgettable event.

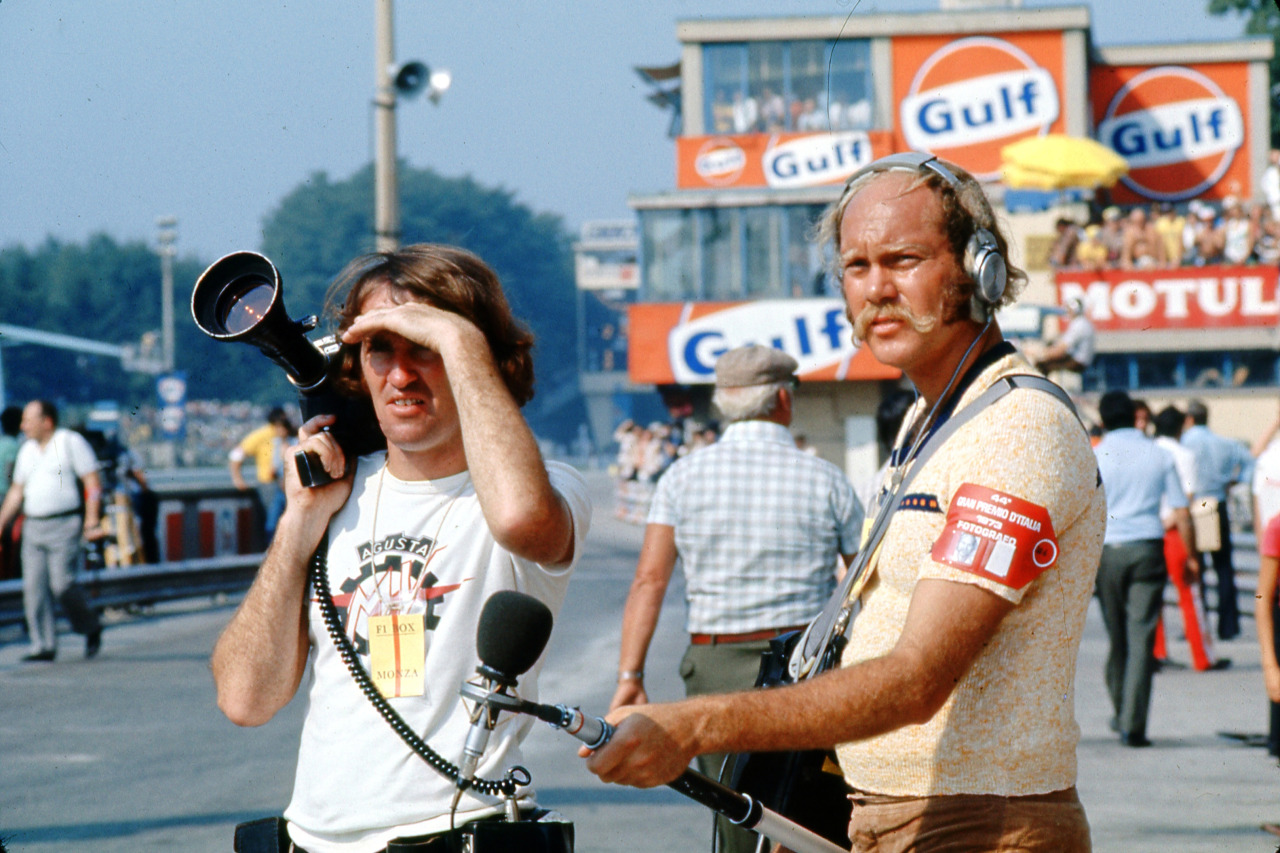

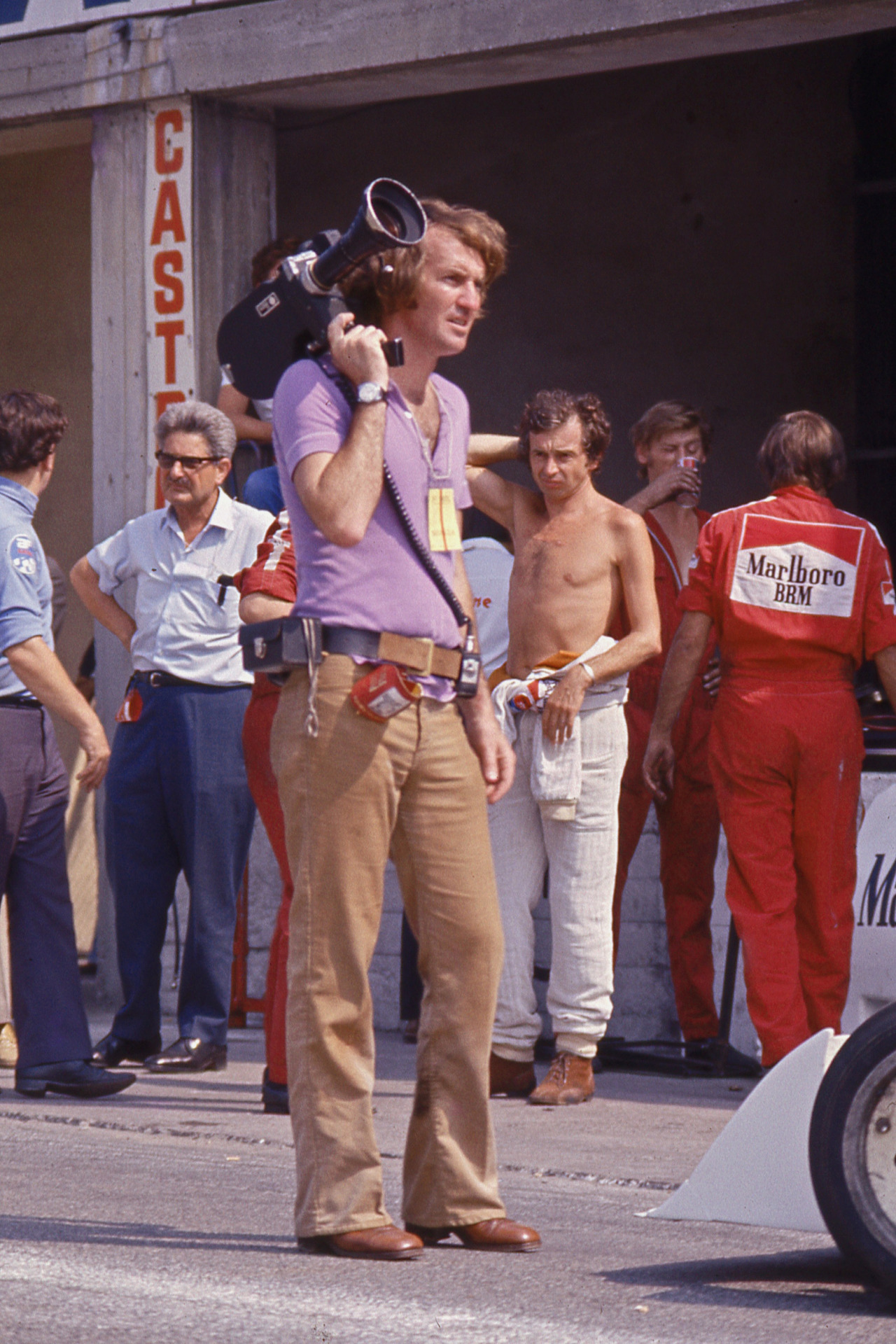

It would also prove to be a life-changing event for the young Leonard men. Equipped with Michael’s roll of film shot at Zandvoort and without any admissions passes, limber and long-haired they successfully crawled through a hole in the fence in August 1973 to access the Austrian Grand Prix held at the Osterreichring in Zeltweg. Amidst the thousands of faces they came upon eagerly anticipating the 54-lap race, was a tanned easy-going guy clad in a Marlboro t-shirt carrying a big movie camera on his shoulder.

“I had no idea who he was,” recounts Mark, upon first meeting John Tully, owner and cameraman of London-based Brunswick Films that was sponsored at the time by Phillip Morris out of Lausanne. “We went up to him and showed him the Williamson crash photos.”

Tully hired them on the spot – in exchange for passes.

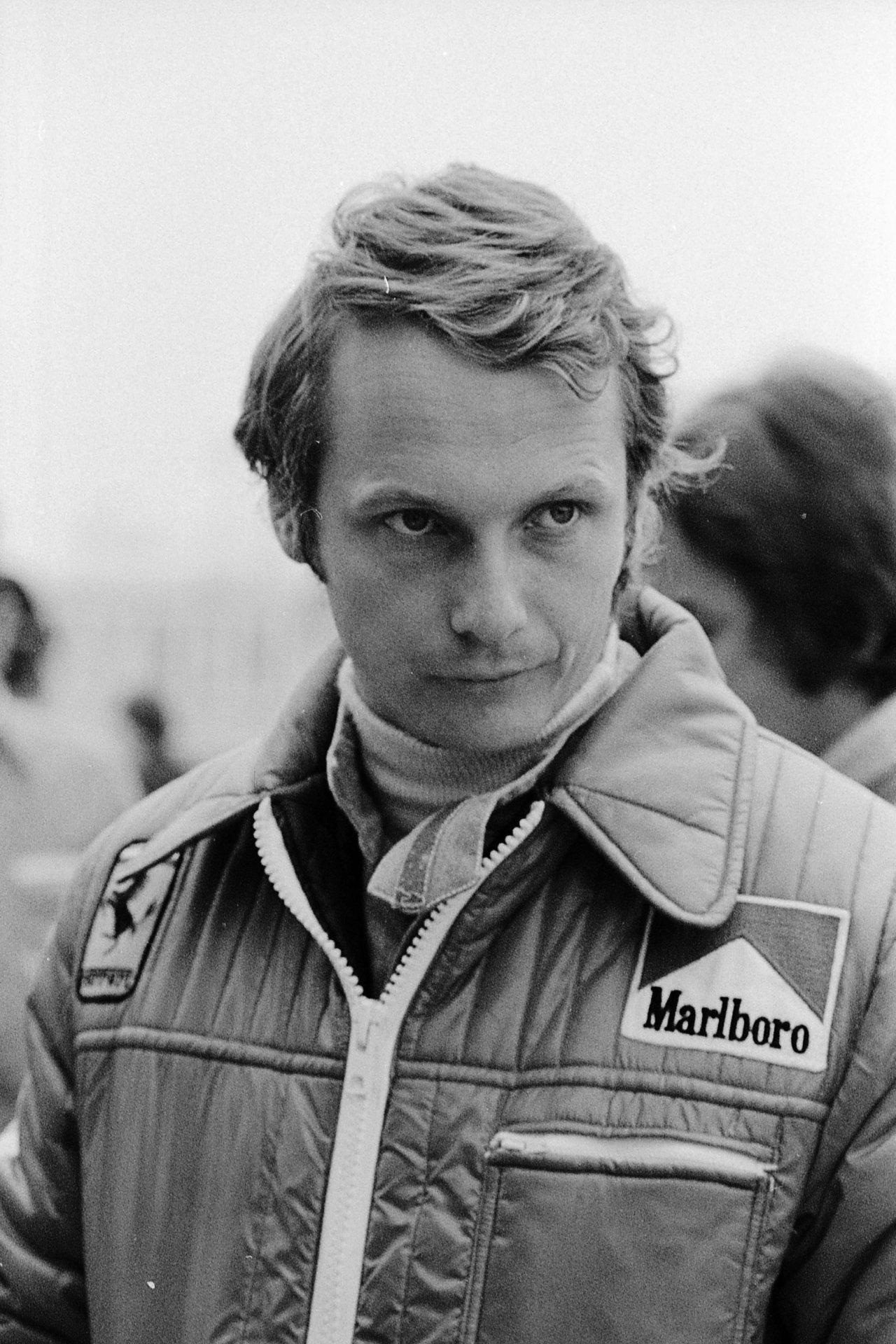

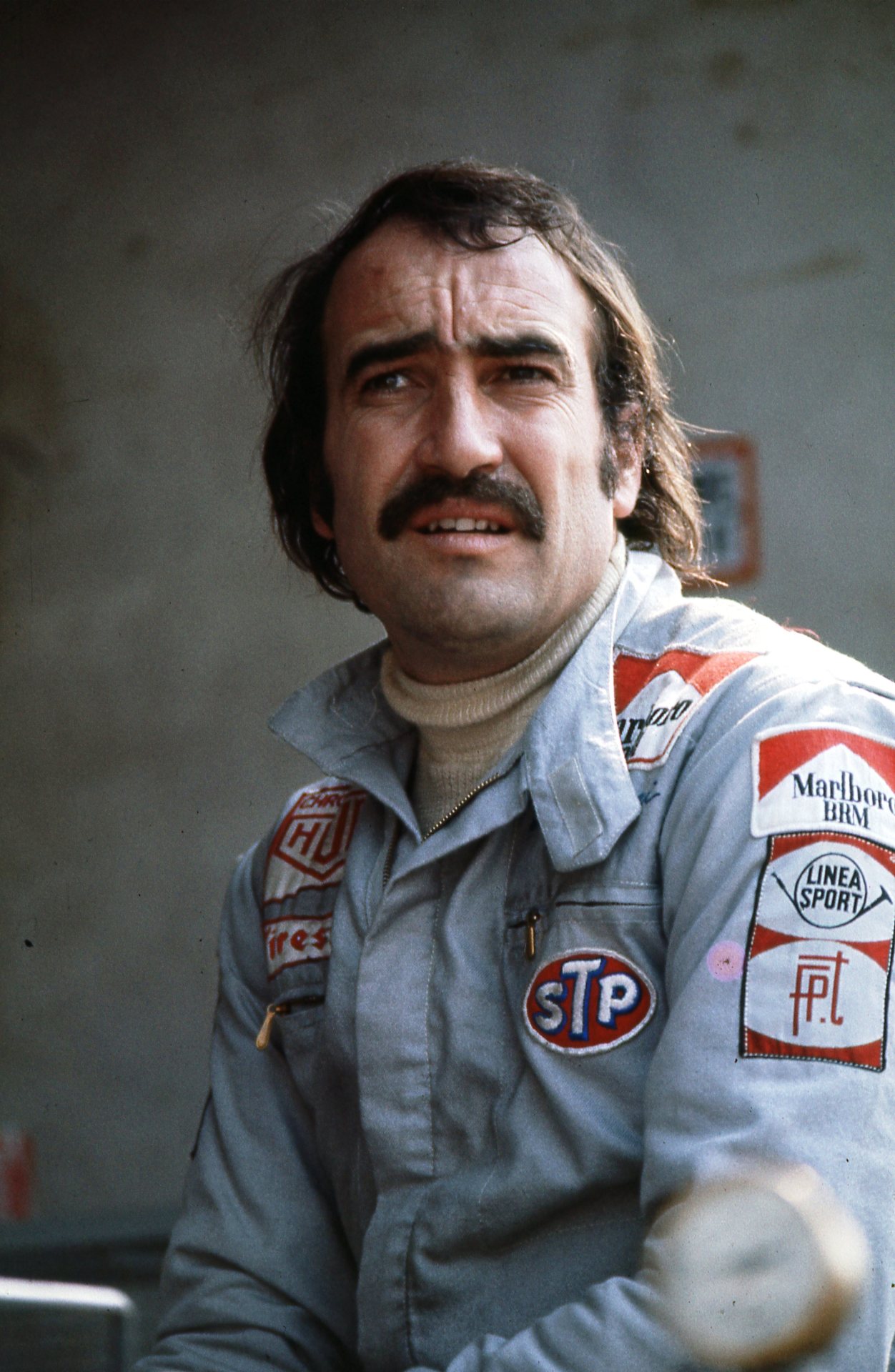

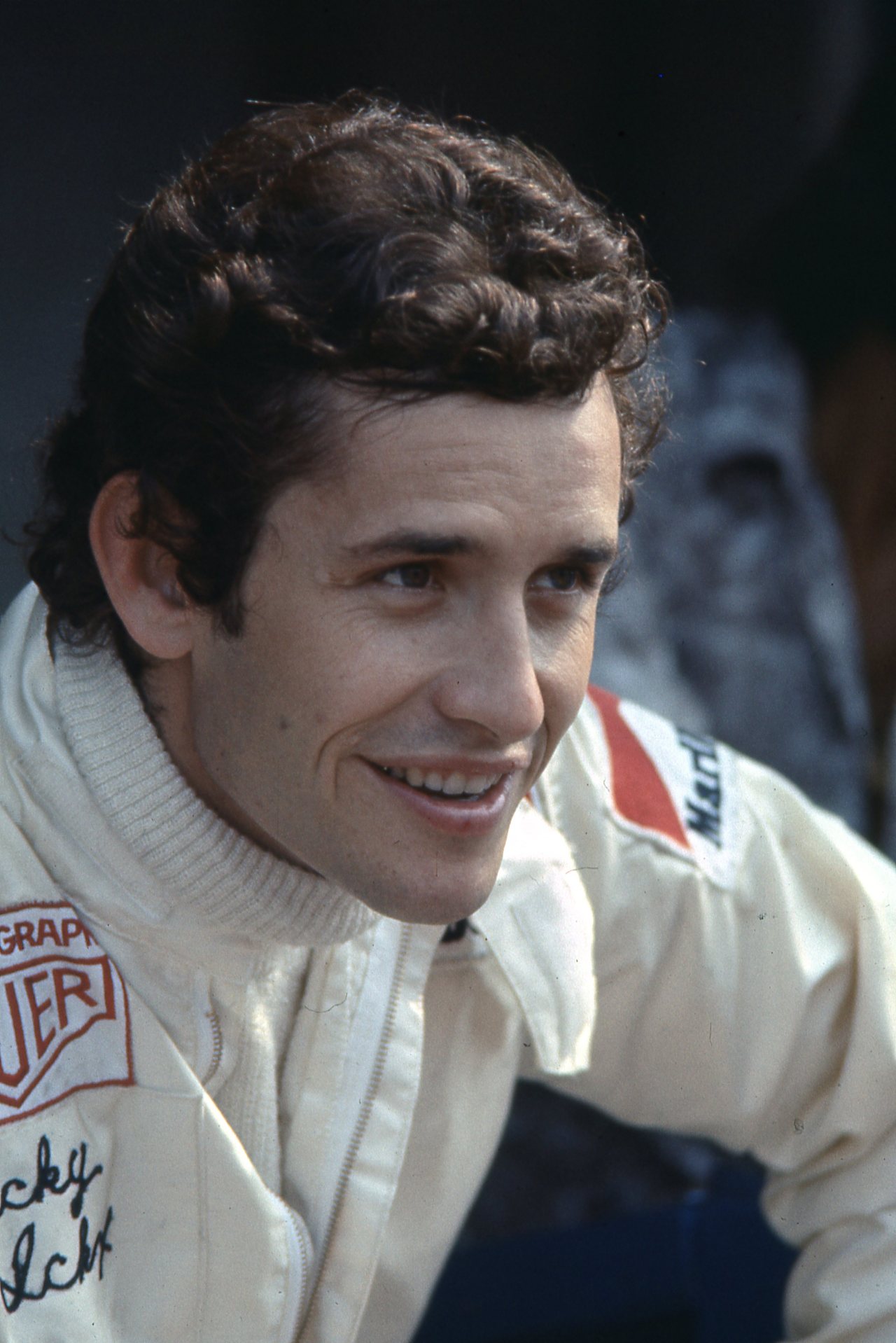

“From that point on, whatever the racing venue, I did my best to fit in everywhere,” adds Mark as he describes how he and his brother who were near Frankfurt, Germany, quickly found themselves at the heart of the racing world while working for Tully until 1977. Whether he was driving the Ford Transit van, taking still photos, helping load camera magazines into movie cameras, or holding sound booms for movie stars and celebrity driver interviews on Tully’s yacht in Monaco, Mark operated during Formula One’s golden age. It was a highly competitive time when the racing greats such as James Hunt and Niki Lauda, and so many others, wildly popular, spoke to the raw, simmering emotion of the time. Known as the Hunt-Lauda era, (from 1973 to 1979) a fierce and merciless Formula One rivalry, (documented in Brunswick Films’ many documentary films of the era and then later, Ron Howard’s film, Rush 2013), it was a time of pioneering car design, highly talented drivers, when the drivers were so much more accessible to the fans, and when corporate sponsorship didn’t completely call the shots through censorship.

F1 sponsorships were in their early days. Marlboro’s first foray into sponsorship was in 1973 with the racing team, British Racing Motors (BRM). Marlboro then moved on to McLaren in 1974.

“It was a time of passion, intensity and danger,” muses Mark as he reflects on the fierce competition and risk he observed in the sport. He remembers being at the Nurburgring in 1976 during the F1 German Grand Prix when Niki Lauda dodged death after crashing his Ferrari. It was a racing age where drivers were deified by danger and glorified.

One memorable experience for Mark was in Monza, Italy when he was asked by Tully (who had heard about his motocross prowess), to ride the Honda mini-bike so that Tully could perch behind him back to front, holding his film camera. Filming the foot race (where drivers and team owners raced around the circuit on foot), with Mark adeptly smooth on the throttle, Tully zoomed in on Frank Williams achieving first place, followed by James Hunt in second. The challenge for Mark was having to navigate the bike through the throngs of exuberant fans as they swarmed the circuit for the finish of the foot race just as if it were the chequered flag of the car race.

“It was surreal,” he laughs. “Thousands of crazy Tifosi fans spilling onto the track after the race!”

With Mark’s work ethic and photographic talents not gone unnoticed, it was also in Monza that Mark was later asked to set up a film camera on the circuit for the 1973 Italian Grand Prix. Not unlike the way his brother just happened to be perfectly positioned to capture the Williamson crash, Mark too just happened to capture the 5-6 seconds of incredible comeback footage of British legend, Jackie Stewart’s Tyrrell Ford 006. Stewart had had to make a pitstop with Mark capturing the final overtake for position that gave Stewart enough points to win the Driver’s Championship.

A sport where drivers truly lived on the precipice of glory and death, the young photographer experienced for himself just how quickly things could change. In October 1973, Mark found himself at the center of the action of the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, New York. On the heels of his success at Monza, Jackie Stewart was possibly poised to do it all again. But there was to be no victory lap; French driver, Francois Cevert was killed during the Saturday practice after he crashed violently in the uphill Esses. Devastated, Stewart immediately withdrew from the race in honor of his friend and teammate. It was a powerful tribute that for Mark encapsulated a fundamental human side to this sport in the 70s. Despite the incredible risks and the horrors that ensued, the indelible bonds of a brotherhood prevailed.

Call it serendipity, or simply a gifted, hardworking young man in pursuit of his passion, Mark’s 4 years of F1 exposure with Tully and Brunswick Films laid a remarkable foundation for his entrepreneurial success to come. Mark relocated to La Jolla, California in 1979 where he started Grand Prix Classics. His beautiful showroom and on-site restoration workshop currently houses some of the world’s finest classic cars for sale.

Mark opens up one of the many photo albums he has archived in his office. He hovers over a black and white photo he took in 1974 at Jarama, Spain. Niki Lauda, #12 is in the cockpit of a 1974 Ferrari 312B3 pulled up on the pit lane. Mark pulls out another album. The exact same car makes an appearance in another photo. This one is in color and shows it parked in the Grand Prix Classics showroom.

“It sold for $4 million,” he says with a wide smile. “Who could have known!”

Forty-five years later, Mark Leonard can safely say it has been quite a ride.

Story by Mark Leonard