Two men, a Porsche Carrera GT, and one rather crazy idea.

That’s all we’re saying for now.

Le Mans was just around the corner. That always makes me wistful. Because I always wanted to race there myself (if I’d actually made a career as a driver). And because Jo Gartner died there thirty-nine years ago, on the Mulsanne Straight. Just after three in the morning. A mechanical failure on his Porsche 962, probably a broken rear suspension. There’s no TV footage of the crash, only a ghostly one-minute-twenty-seven-second clip on YouTube. The white headlights crawling for more than two hours behind the pace car after the accident. A snapped telephone pole, the splintered branches of a tree. The Porsche first slammed into the pole with unimaginable force, then shot off into the woods. The eeriest part was the debris scattered everywhere. On one piece you could still make out Jo’s name and the red-white-red Austrian flag.

Still, I can’t seem to let go of Le Mans – the mother of all races. I’m there every year, even if only as a chronicler.

Late May, about two weeks before heading to France once more, I visited my friend Armin near Stuttgart. He picked me up from the airport in his silver Porsche Carrera GT. He owns other weapons of similar caliber. What you should know about the Carrera GT: its 612-hp, 5.7-liter V10 mid-engine and carbon-fiber monocoque chassis were originally developed for a Le Mans prototype that was supposed to debut in 2000. The project was canceled for cost reasons. So what do you do with engine and chassis? Exactly – put ’em in the Carrera GT! Production started in 2003. A total of 1,270 cars. The body also made of carbon fiber. Price tag: €462,690. Current value: about €1.2 million.

On the A8 – heading toward Armin’s cozy home, the Carrera GT ironing out the left lane in sixth gear – a completely nonsensical idea hit me: we’d use the car for our own personal Le Mans. Twenty-four hours in circles. Somewhere around here. A loop ten to twenty kilometers long (the Circuit de la Sarthe measures 13.6 km). We’d swap every two hours – one drives, the other rests at Armin’s place. I got so excited I blurted it out right away. Armin’s answer: “My time’s too precious for something that stupid.”

But at breakfast the next morning, after his first sip of coffee, he said, “I’ve slept on it. When do we start?” The casual tone in which he said this didn’t match the eager look he gave me over the rim of his cup. First we needed to find a good route. A former colleague from the area volunteered to help and handed us a roadbook that really packed a punch. Short version: “Start in Weilheim an der Teck. Out of town, turn right toward Bissingen. Long curves to Nabern, then a short straight to the B465. Hard braking before a right-hand kink onto the B465 toward the A8. On the A8 toward Munich, flat-out to exit 58. Switchbacks back to Weilheim. About 20 kilometers.”

We started at 4 p.m. on a Saturday – just like the real 24 Hours. Armin took the first stint. Since it’s about 30 kilometers from his house to Weilheim, he left at half past three. “So who actually wins?” he asked as he was heading out. “Hm, there’s only one car and we’re teammates,” I said. “Still, someone has to win. The one who drives the most kilometers?” “No, I’d lose my license again.” “The one who burns the most fuel?” “Comes to the same thing.” I finally convinced him we didn’t need a winner. It was to be our shared triumph over life’s self-righteous seriousness. We high-fived a goodbye and he disappeared out the door.

My stint began around 6 p.m. We couldn’t plan it to the minute – each lap had to be finished. And since the driver changes were to take place in Weilheim (Kirchheimer Straße, across from Beate Ott Frisuren, the local hairdresser’s salon), I had to get there somehow. Same for Armin later. Our shuttle car: a Ferrari 512 BB Competizione. For reasons of proper protocol, of course. The car is cleared for Le Mans Classics through 2027. We’d briefly considered swapping roles and using the Porsche as the shuttle, but that was too risky – the Ferrari’s over forty years old, and it was doubtful it would survive 24 hours of continuous stress. Besides, the cabin heats up to 90 °C.

To fire up its V12, I had to press a few buttons, turn a lever, flip a switch. Then – the Big Bang, that gloriously dirty Emilia-Romagna growl from five liters. The smell of oil and gas. I slammed it into first and rolled out. It got hot fast, and after a few kilometers sweat was dripping down my forehead.

Driver change in Weilheim. Armin climbed into the Ferrari and headed home. I got into the Porsche and launched into our “Petit Le Mans”. (There really is a little Le Mans, by the way – a ten-hour race of the American IMSA series at Road Atlanta in Georgia.) Key in the ignition. “Wham!!” The revs shot sky-high. I let the ceramic clutch out slowly and completely – short pedal travel – only then did I hit the throttle. The line between stalling and launching is razor thin.

The cockpit was far more civilized than the Ferrari’s. A landscape of leather and magnesium. The steering wheel and five classic round dials from the 911. The beechwood gear knob (a nod to the 917). Kevlar-carbon seats that fit like a glove. Above me, the roof made of two removable carbon shells.

Armin had started with a full tank – 92 liters, now nearly empty. I’d asked him not to tell me how many laps he’d done, but based on his fuel burn – about 85 liters in two and a half hours – I could guess. Say eight laps, 160 kilometers. That’s 53 liters per 100 km. Enough to get a Mazda2 Hybrid from Hamburg to Rome.

Behind the wheel of a Carrera GT, everyone develops main character syndrome. So too yours truly. Anyone on the autobahn who didn’t immediately and humbly clear the left lane got a frosty glare as I blasted past. You could hear us from kilometers away – the GT and me. Michael Hölscher, the project leader of the Porsche 980, once confirmed this indirectly on the Motorikonen podcast. He’d driven a brand-new GT up the A81 from Singen twenty-plus years ago. “The next morning,” he recalls in the podcast, “a mechanic asks me, ‘Mr. Hölscher, were you by any chance driving up the A81 around eleven o’clock last night?’ ‘Yes, how do you know?’ ‘I live five kilometers away!’”

In Weilheim an der Teck (pop. 10,000), word had spread that every couple of hours a Porsche and a Ferrari pulled up across from Beate Ott Frisuren, two guys climbed out, swapped cockpits after a few words, and roared off again. By the fourth driver change – well after midnight – about fifteen people were waiting for us. “What are you guys doing with your insane rides?” asked a dark-haired youngster in a leather jacket, arm around his girlfriend. “I’ll tell you,” Armin began. “We’re looking for lost time. Somewhere around here we must have misplaced it. We have to hurry before some new Proust shows up and steals even more of it from us – 4,000 pages’ worth – until there’s none left. That’s why we have these two rockets here. Get it?”

The guy clearly didn’t, starting with the first few words out of Armin’s mouth. “Uh, I don’t really care about all that time stuff,” he said, “but can I ride along? Either car.” “No passengers allowed,” Armin said. “I’ll pay you two hundred euros!” “Don’t be ridiculous,” his girlfriend cut in. “They’ve got money to burn – a hundred euros is pocket change for them.” “Two hundred!” he insisted, pulling out his wallet. Armin smiled mildly. “Keep it. The rules don’t allow it.” I felt sorry for the guy – and honestly wouldn’t have minded the cash. So I offered a compromise: in about 16 hours – around 4 p.m. – our search for lost time would end right here, and I could give him a lift to Armin’s. He’d have to find his own way back, though.

That night, heavy rain set in. I had to be insanely careful not to aquaplane on those monster 335 tires and end up in the weeds. Truly no fun. Never had I wished harder to be in a Citroën 2CV, whose spindly wheels carve two tiny Panama Canals through even the deepest puddle so the car can glide safely through and regain dry footing. But no one ever said Le Mans was a leisurely country drive.

Traffic and weather had so far kept us from breaking the 334 km/h barrier. Then I was reminded of Hölscher again, the former Carrera GT project lead, who said on that same podcast: “For us, top speed was never the key metric – lap times were. When we say a car is fast, we don’t mean km/h, we mean seconds. The biggest test was, of course, the Nordschleife.” In 2004 Walter Röhrl blasted the Carrera GT through the Green Hell in 7 minutes 28 seconds. Too bad that four years later, little-known German driver Marc Basseng (2012 FIA-GT1 World Champion with Markus Winkelhock) beat that time by three seconds in the Ferrari Enzo – 20 km/h faster. Winner, then, in both km/h and seconds.

Four a.m. My third stint done. I collapsed on the couch, set an alarm on my phone, and tried to sleep. No luck yet. Even now my adrenaline levels, fed by engine noise and GT performance, were slow to drop. I was working on a story about Sir Barton, the greatest racehorse of all time, for a magazine – and suddenly wondered if he’d had a comparable hormone rush when, in 1919, he thundered down the last 100 meters of the Kentucky Derby toward the Triple Crown title with jockey Johnny Loftus on his back. I made a note on my phone: “Research whether horses have measurable adrenaline levels.” Then, finally, I fell properly asleep.

The rain had stopped. “We cracked 334,” Armin said at the driver change. Modern Le Mans prototypes don’t do much better. The highest speed ever measured on the Sarthe – 405 km/h in the green-and-white WM P88 from Welter Racing, 1988 on the Mulsanne Straight – remains an eternal record, thanks to the chicanes added in 1990 for safety reasons (no more Jo Gartner incidents, please).

I cruised along the country roads, thinking of my upcoming trip to Le Mans. This time I’d be watching mostly from the box of the Alpine team and thanks to the hospitality of my French friends. Second entry in the Hypercar class. And of course I’ll be rooting for my fellow Austrian Ferdinand Habsburg – that cool great-grandson of Austria’s last emperor. His teammate, by the way, also of distinguished lineage: Mick Schumacher.

So yes – from my side too: 334 km/h on an empty Sunday autobahn was child’s play.

The final stint. Armin drove. I waited in Weilheim with our little fan club. The young guy – Patrick, his real name – stood there, chest out, waiting for his big moment. A few people clapped as the Porsche rolled up to Beate Ott Frisuren for its final meters. Armin stopped and killed the engine. Our Petit Le Mans, our search for lost time, was over. We’d made it. The Porsche too. Armin, dead tired and with panda-bear circles under his eyes, climbed out and slipped into the Ferrari one last time. Patrick and I squeezed into the Carrera GT. The kid was beside himself, eyes misty, thanking me nonstop. At the end of the ride he handed me the two hundred euros, hesitantly – hoping I didn’t actually need the cash. Wrong. I took the bills and stuffed them into my pocket. He asked who actually owned the Porsche and the Ferrari: “Your friend or you?” “Me.” “What do you do for a living?” “I collect money and count it day and night.”

Armin and I slept twelve hours straight. Then we went out for a fine dinner in Stuttgart and shared a bottle of champagne. A toast – to us, to that electrifying Porsche Carrera GT, and to the 24 Hours of Weilheim.

Back in Vienna, I went to the animal shelter and asked for the ugliest dog nobody wanted. They showed me a pitiful creature – it took three looks to even tell it was a dog. I gave the shelter two hundred euros and took him home with me on the spot. Turns out Petit Le Mans did have a higher purpose after all.

Porsche Carrera GT

- Engine naturally aspirated V10

- Displacement 5,733 cc

- Power 612 hp (450 kW) at 8,000 rpm

- Torque 590 Nm at 5,750 rpm

- Weight 1,380 kg

- 0–100 km / h 3.9 s

- Top speed 334 km/h

Text Kurt Molzer| Photos Matthias Mederer · ramp.pictures

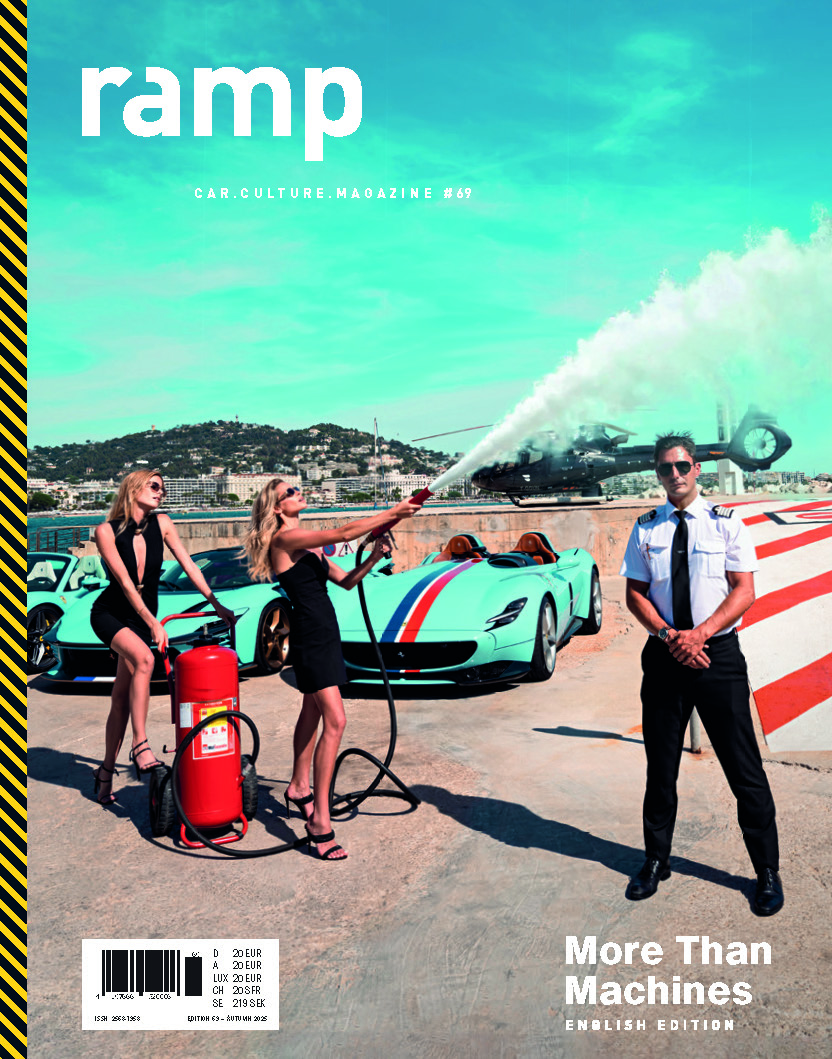

ramp #69 More Than Machines

Maybe it all starts with a misunderstanding. The mistaken belief that humans are rational beings. That we make decisions with cool heads and functional thinking, weighing and optimizing as we go. And yes, maybe sometimes we do. But only sometimes. Because in truth, we are not reason, we are resonance.

And so this issue of ramp is a cheerful plea. For beauty that needs no justification. Find out more