Car enthusiasts celebrate the extremes. The fastest. The rarest. The most race wins. The most valuable. While most of us don’t have a vehicle in the garage that can make one of those claims, we’re nonetheless interested in the vehicles that do. The market for those vehicles should interest us too. The reason is simple: Vehicles at the top of the market often set the pace for those that follow.

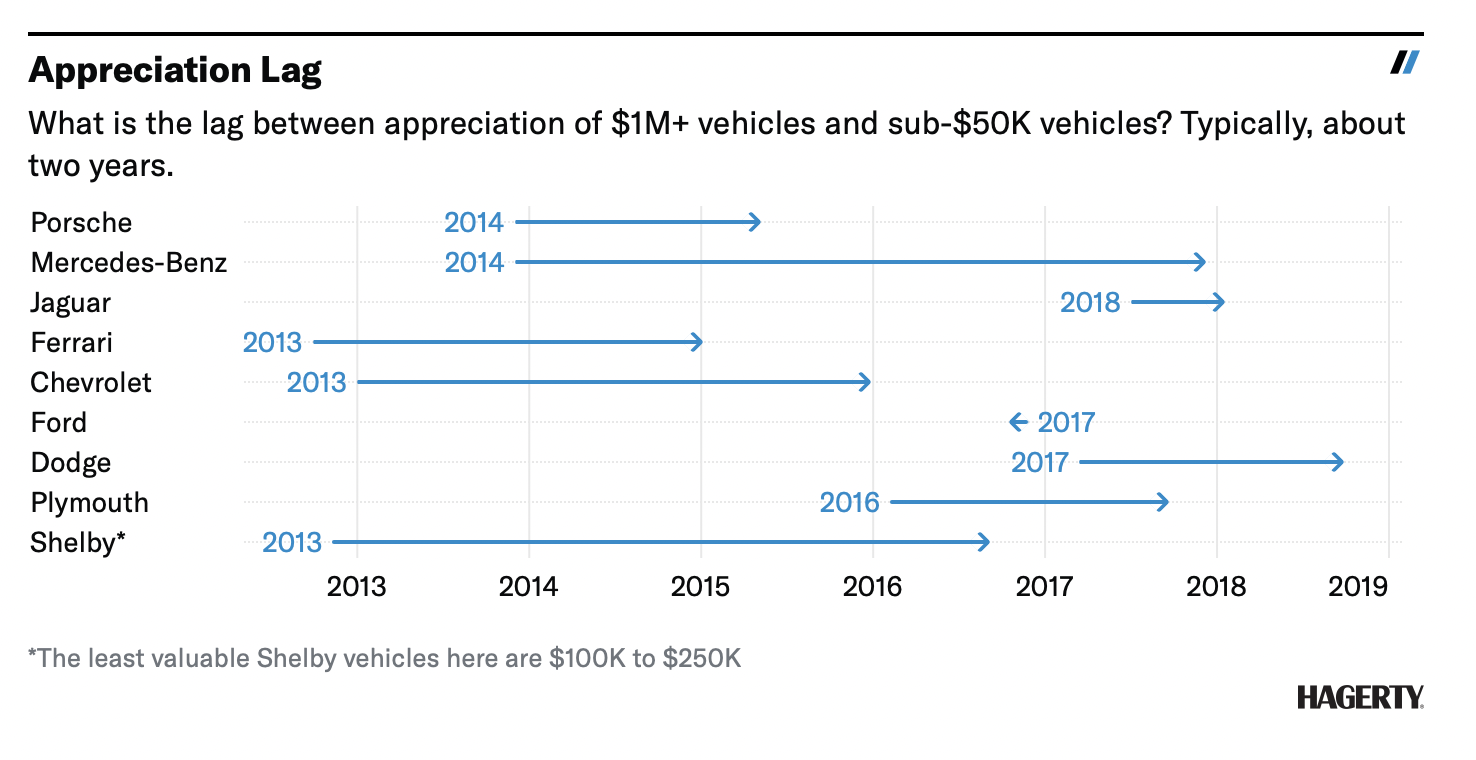

This isn’t just vague “trickle down” theory—we have data to prove it. We examined some 3,500 vehicles in the Hagerty Price Guide from popular makes with vehicles ranging from $10K to $1M+ and see a clear trend: When the most valuable vehicles ($1 million+) from a brand have appreciated at least 10 percent year-over-year, less valuable ones from the same marque tend to appreciate about two years later. For instance, Porsches that crested the $1M+ level typically started appreciating the most in late 2013. At the other end of the Porsche value range, those models with a condition 1 value of less than $50K typically saw strong appreciation by early 2015 (or 1.4 years later). In some cases, the lag is longer—attainable cars from Mercedes-Benz took an average of 4.0 years to echo gains in the more expensive ones. Some were much shorter: The lag for Jaguars was just six months. But the trend is almost universal—the more valuable cars lead the way. The only outlier is Ford, which saw mid-market cars appreciate first (late 2014) and then more and less valuable Fords appreciated about two years later.

Correlation doesn’t necessarily mean causation—there are lots of reasons different cars appreciate at different times, including the differing ways in which the economy impacts high-net-worth people and everyone else.

Yet there are clear mechanisms by which high-end vehicles can drive up prices for those on the lower end. One is Principal of Substitution. If a $100K vehicle appreciated 10 percent or more in the past year and is now beyond a certain shopper’s budget, they might very well look for a similar car (a substitute) still within their price range and buy that instead. Naturally, appreciation for the lower-priced vehicle follows. This substitution effect can travel far down the chain—just ask folks in Oakland or Queens how real estate prices in San Francisco and Manhattan have impacted their rent.

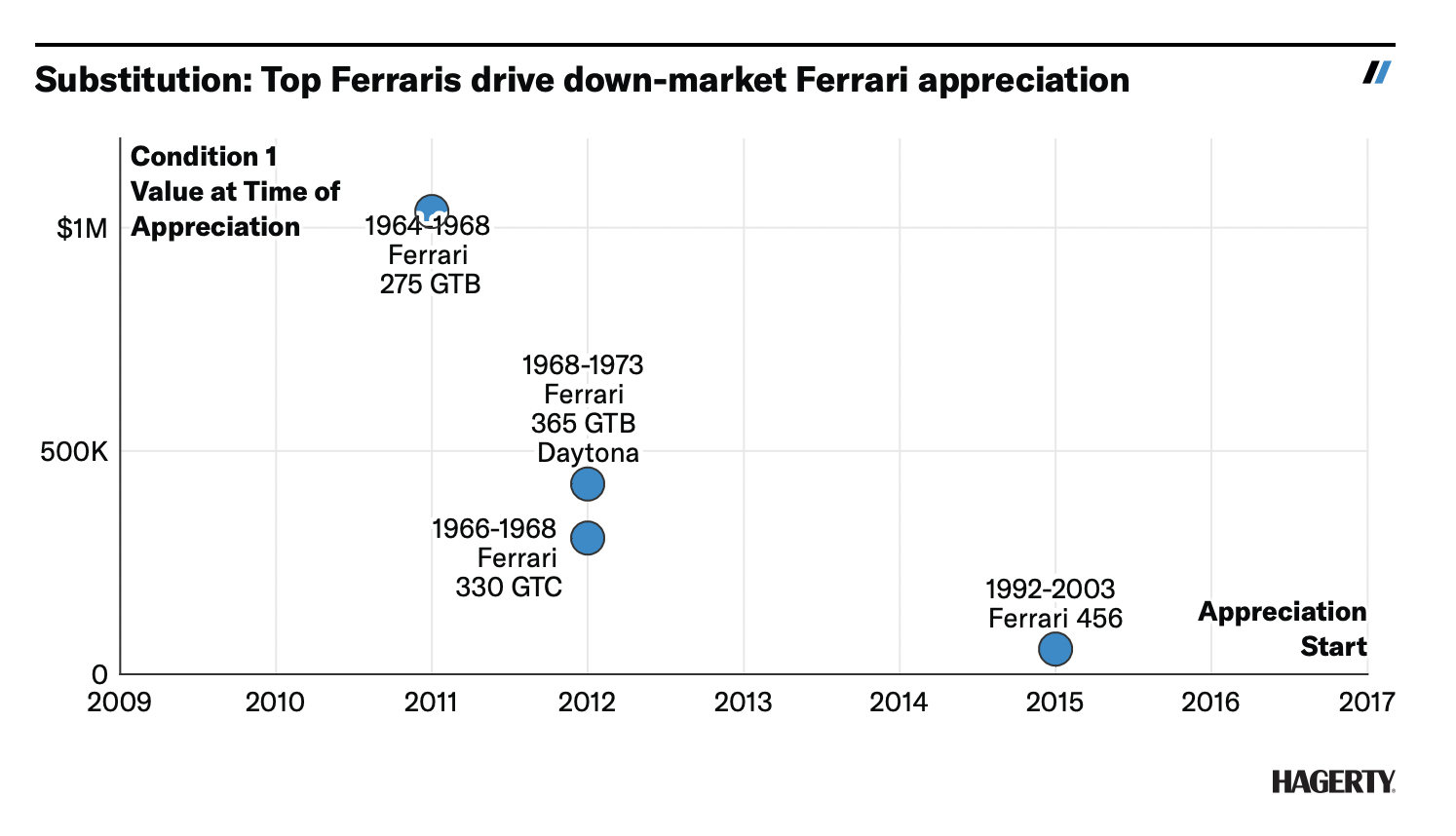

To break it down further and demonstrate the spectrum of substitution from the top end of the market through the middle on down, it makes sense to share a few examples with specific cars. Given that Ferrari’s average lag is closest to the average for all marques considered, we’ll start there.

Since 2010, the 1964-68 Ferrari 275 GTB (current Condition #1 value: $2M) has appreciated at least 10 percent year-over-year many times, but 2010-2011 was the first period of notable appreciation, with an increase of 22 percent in one year. The less valuable but similarly collectible 1966-1968 Ferrari 330 GTC (currently $615,000 average condition 1 value) didn’t start until the following year, when it gained 36%. Similarly, the 1968-1973 Ferrari 365 GTB/4 Daytona also begins to appreciate materially between 2011 and 2012. Further down the price scale, the 1992-2003 Ferrari 456 started to appreciate between 2014 and 2015, achieving an 11 percent increase.

Chevrolet’s average lag of 3.0 years is also close to the overall average. Not many bow-tie cars have exceeded the seven-figure mark, but the 1967 L88 Corvette and the ultra-rare 1969 Corvette ZL1 (present condition 1 value of $3.1 million and $1.7 million, respectively) are a good place to start. The ’67 L88 started to appreciate from 2012 to 2013, increasing 24 percent in that period. The ’69 Corvette ZL1 saw its own 10 percent increase from 2011 to 2012. Heading a little lower on the Chevy Muscle price scale, the 1969 Camaro ZL1 first saw a material increase in value (24%) from 2013 to 2014 —after those monster Corvettes began their upward trajectories. Over the same period, the 1970 Chevrolet Chevelle SS 454 LS6 followed suit, appreciating 14 percent. Even lower on the price scale, cars like the 1969 Chevrolet Camaro SS Sport Coupe with the L48 350cid/350hp began appreciating between 2016-2017, landing itself a 10 percent increase.

The marque with deviant data in this exercise is Ford, which has almost no lag between the least valuable models and the most valuable ones. The reason could be simple: people in the market for a 1964-1969 GT40 are unlikely to substitute it with a Mustang or Thunderbird, so the top of the Ford market is somewhat detached from the middle and entry level. There does appear to be evidence that the Fords valued in the hundreds of thousands of dollars do appreciate ahead of those with less value, so the theory holds, albeit with less range.

Substitution and lagging appreciation only function when the market is ascendant, however. In a down market, there’s less correlation: for some makes, including Ferrari and Chevrolet, the most valuable cars depreciate last. In contrast, makes such as Mercedes-Benz, Jaguar, and Ford, tend to see the most valuable cars depreciate first. As the opportunities for a substitute in a falling market are reversed (more desirable models are now available), the variation may instead reflect the differences in consistent (Ferrari) and more varied (Ford) model hierarchies.

We’re sometimes asked why we pay such close attention to top-flight cars when the majority of enthusiasts have more accessible collector rides. Aside from geeking out about the rare and important cars that are historically relevant to the car hobby writ large, the value trajectories of those at the top of the market give us critical insight into the performance of the market as a whole. Lagging appreciation and substitution are just two facets of how these cars influence our hobby.

Report by John Wiley for insider.hagerty.com