Get in, drive off, savor the experience. Metallic scraping, whimpering howls, wheels at the limit in the corners. Slam the gears, hit the brakes, get the machine to go where you want it to. We’re talking about the S/T.

Please forgive our impatience when it comes to the historical context of this car. You can deduce any Porsche 911 from its heritage. Marketing departments are crazy about it. At the same time, you could also retroactively deduce all 911s from this model, because it is the fitting nucleus of rear-engined sports car philosophy, the essence of the 911, always gladly invoked, and here, apparently, realized in the most consistent way.

Better still, this is the Porsche for really tough driving, with all due respect and the highest praise. The Porsche as such: 518 near-natural horsepower, rear-wheel drive, manual gearbox, lightweight clutch, rigid, relentlessly loud, rattling, scraping, rushing forward, cutting lanes, always on the move, always on the attack, always reliable when it comes to steering instead of braking. Though the legendary efficiency of the Porsche concept is always an option as well: just slow down when things get too dicey. With stopping power guaranteed by the tried-and-tested ceramic composite brakes (410 mm at the front and 380 mm at the rear).

“The car should really be called Walter Röhrl,” the German rally driver says himself. “This short gear ratio – that’s like having a hundred horsepower more. Though the biggest secret of this sports car is: nothing beats a low weight.” Andreas Preuninger, Porsche’s head of GT road cars, and the man responsible for the S/T, gives us a brief history lesson. He talks about the 911 R prototype from 1963, which was available in a standard sports version. (It was already revving at 8,000 rpm even back then.) He refers to the S as the strongest racing car and the T as the minimalist forefather. There were three versions, but none were allowed to be called S/T, at most S/T package for the purpose of Group 3 homologation. Swift victories at the Monte Carlo Rally, Nürburgring, Safari Rally, Le Mans, Daytona. Porsche engineers developed a backpressure-optimized exhaust system and modified cylinder heads with the corresponding cylinders. In its final evolutionary stage, the 2.5-liter boxer produced 266 hp.

Now it becomes somewhat clear why we wanted to spare you the history lesson. Andreas Preuninger is wearing bright Adidas Samba sneakers to match the occasion. We’re in Calabria, where Porsche usually likes to run its chassis tests on the roads of a thousand hairpin curves (we counted them).

Heritage today: The 911 GT3 has been updated and trimmed down in line with racing principles. It was given a sharp camshaft, a sports clutch with a single-mass flywheel, carbon in the roof, hood, fenders, stabilizer bar and shear panel. The highly complex CFRP doors were taken over from the GT3 RS, so the shape was already predetermined; for the first time, the narrow body was fitted with chubby fenders, resulting in an attractive combination. The CFRP roof also has a new, longitudinally centered shape. The Porsche people apparently were on an aesthetics kick, and they didn’t want to spoil – pardon the pun – this beautiful line with a spoiler (as is usual from 80 km/h). So the wing stays put until the car reaches 120 km/h, and when it finally does rise to the occasion, it does so with relative discretion. A Gurney flap adds the finishing touches.

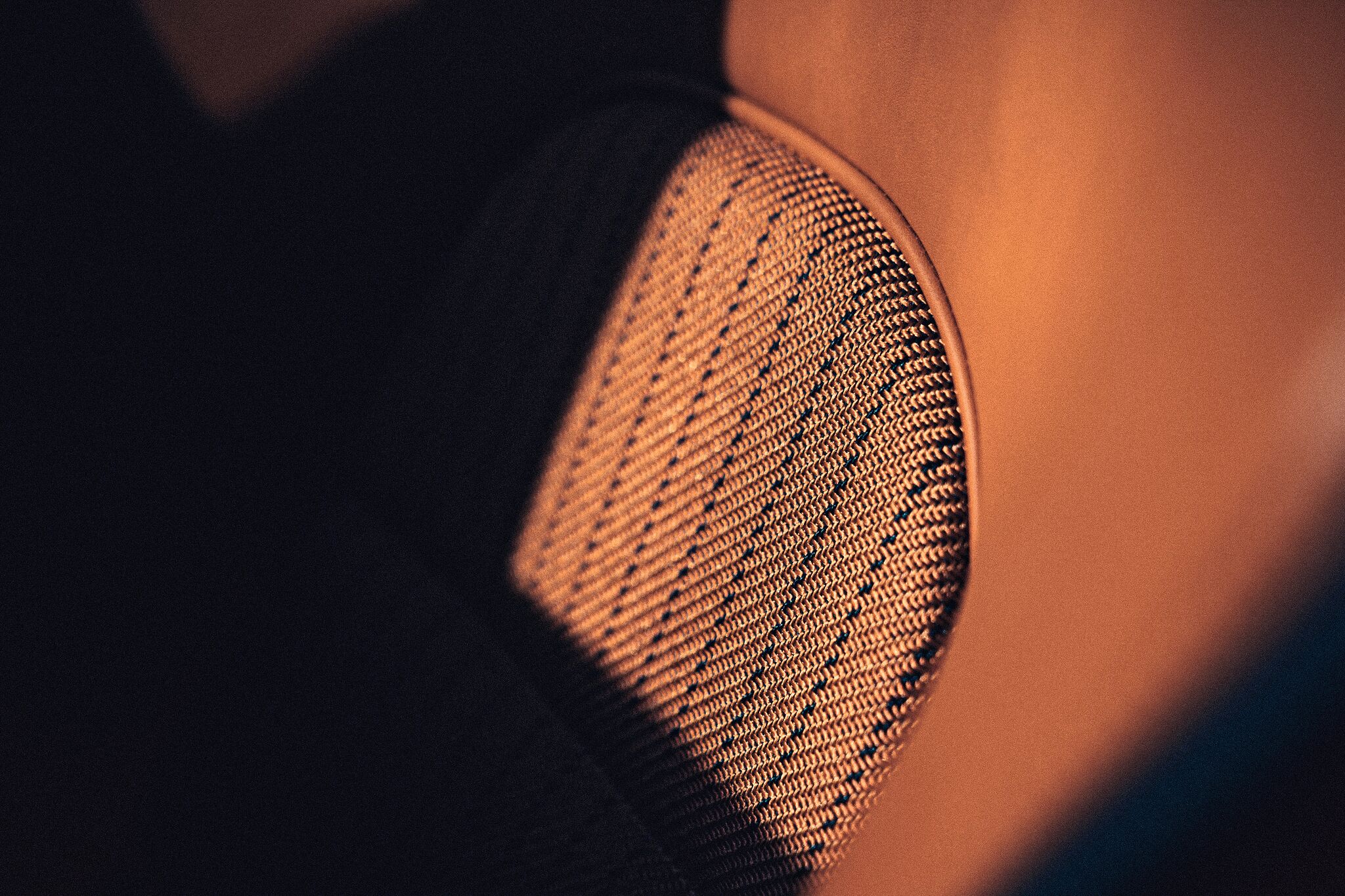

Open the lightweight doors and the first thing that catches your eye are the pinstripes. In this respect, we feel suitably dressed here in southern Italy. The bucket seats are even deeper and their side bolsters even harder than we had feared before getting in. As soon as you’re seated, however, everything’s clear. Rev counter (analog) in the middle, speedometer beside it, satellite gauges all around. The familiar green scales and digits are reminiscent of the blissful days of the Beetle, which has a reassuring effect. You need that, because otherwise all this car has to offer is a lot of noise. Grinding, scraping, howling, rumbling. Eight kilograms less of insulating material. Thin glass, low-pile carpet, fabric loops in the doors instead of metal openers. Lighter battery.

“The car talks to you”, as one of the chassis engineers in attendance remarks prosaically. On the one hand, this is due to the reduced flywheel, whose rotational mass has been lightened by a third: 18 instead of 24 centimeters in diameter, that’s a world of difference. And you can feel that difference with every throttle stroke, as the engine reacts to the slightest input. The stubby, short gearshift lies deep in the leather bed and can be operated smoothly in conjunction with the clutch, which only needs to be released casually to release the flow of power. The whole shifting process is smooth, organically musical, until the groove sets in. Now you’re in flow, this is elementary at the highest level of experience, no electric car can keep up with that, this is driving in its most elevated form, and you’re the driver, machinist, organist at the pivotal point of the space-time axis.

For the first time, this four-liter naturally aspirated engine is available in combination with a manual six-speed gearbox. Its gear ratio has been shortened by eight percent, and each gear has its own character. At 144 km/h, the engine reaches 4,000 rpm, at 300 km/h it almost runs out of steam, although there is still some reserve with a usable range of 9,000. But somewhere along the line, the engineers decided that enough was enough.

You have to be quick at the lever to jump through the gears. The first gear is a mere blip, disappearing abruptly into second, third . . . and so on. In 3.7 seconds to a hundred. But really, it’s about the spectacular agility. The chassis combines the double wishbone front axle with the multilink rear axle without rear axle steering, which in turn saves eight kilograms of electric motor power – although it took a year of fine-tuning to compensate for the long wheelbase in terms of maneuverability. The steering was designed to be more direct, thank you for that.

The naturally aspirated engine is allowed to rev up to 9,000 rpm, which is a veritable mark of technical excellence. To achieve this level, the engineers dispensed with hydro-balancing and adjusted the performance as in racing engines. The exhaust experience button makes little sense, the engine doesn’t sound very nice in terms of its sound design, but loud and whining, completely unadulterated. Always this metallic scraping under load, similar to straight-toothed racing gearboxes. The sound button was just there and had to be installed. The same goes for the damper hardening button, the importance of which is usually overestimated. Röhrl never presses it. Just roaring along does little good. Uniball joints ensure high chassis precision, just as the entire system, starting from the double wishbone front axle, is set up for abrupt load changes from spontaneous turn-ins into the bend even at high starting speeds. The lightweight, torsionally rigid CFRP stabilizers keep the tilt angle as low as possible to improve cornering stability.

A good reason to buy this car is the absence of a start-stop function. PSM can be switched off completely.

Magnesium rims significantly reduce the unsprung mass. Compared to the lightest GT3 Touring version, the S/T is another 138 kilograms lighter overall.

The rest is marketing (limited to 1,963 units!) and a choice of beautiful colors. The new Shore Blue Metallic or the blue from the Heritage package are especially appealing. Two-digit starting number freely selectable. Everything looks great in the living room garage. There’s also a special dust cover and you can have the key painted in the color of the car. LED projectors shine the “Icons of Cool” logo onto the asphalt next to the doors when they are opened. There’s no getting around it, even individualism is preformatted these days. But you can always tape it over.

In this same spirit, Porsche has also issued a new chronometer to go with the car, always matching the vehicle number that is embossed on the gold-plated badge on the passenger side. The winding rotor behind the seven-times anti-reflective glass looks very similar to the rim design. Another subtlety: the so-called flyback function allows a running time measurement to be interrupted at the touch of a button and a new one to be started immediately. This combines the three steps “stop”, “reset” and “restart” into one.

So in a way, you can explain the entire 911 heritage with the press of a thumb.

Text David Staretz

Photos Matthias Mederer · ramp.pictures

Driver Sabine Köckritz

ramp #63 Happy on the Road