Sixty years ago, Can-Am race cars were the most powerful, wildest-looking, most step-back-in-fear deafening, and scary-fastest road racing automobiles on the tracks of their time. Faster, even, than Formula 1 cars. And this photojournalist had the incredible good fortune to be there. Yes, it was a crazy-wonderful time.

Can-Am was short for Canadian-American Challenge Cup Series. Born in 1966, the nearly unlimited, big-power sports-racing machines of that unforgettable era could be seen as a noble quest to establish “no-rules racing.”

Technical freedom is rare in motorsports. Of the numerous different kinds of competition vehicles across the competitive landscape–all the cars, bikes, boats, and planes–most are weighed down with regulations and restrictions to limit their performance. Racing is commonly thought to be only about speed, but most racing machines aren’t allowed to go as fast as they could.

Technical limits on speed are not necessarily bad, and safety is always a valid concern. But the no-holds-barred Can-Am was a true child of the psychedelic ’60s, launched in company with rockets to the moon, muscle cars, heart transplants, computerization, student protests, and seemingly every other sort of revolution. Remember Woodstock? Boundaries were being tested in every dimension of life. Adventure was in the air.

Can-Am was the right idea at the right time. Enthusiasts wanted to witness and experience the dizzying advancements in race car technology, so the novel series enjoyed healthy sponsorship and consequently lavish purses. Those, in turn, attracted top drivers, teams, and manufacturers from around the world. Almost all the great road racers of the era tried their hands at the “Big Bangers.” Can-Am also gave free license to some of the sport’s greatest designers, crew chiefs, mechanics, technicians, and craftspeople. The series visited most of North America’s finest road-racing courses.

Thus, fittingly, everything about the new series was big—cars, stars, dollars.

Big Dollars

Thanks to Johnson Wax, the earliest major corporation to bring brand-integrated sponsorship into a sporting series, the “J-Wax Can-Am” offered prize money that was enticingly lucrative to racers. Entries flooded in, not only from established drivers and teams in sports car and F1 racing, but also from IndyCar and even NASCAR. Major entities such as Chevrolet, Ford, Goodyear, Gulf, and Porsche came aboard. The hoopla brought media attention, which brought hordes of fans. Managers of all the best road-racing circuits wanted to host “The Million-Dollar Can-Am.” A million dollars was a lot of money back then.

Cleverly, the new series was initially conceived of as a short string of six rounds to slot between the three North American F1 grands prix that were held every autumn. Visiting world championship contenders were happy to spend their off weekends driving for dollars. As were the race fans who were eager to watch them.

In contrast to the “starting money” system then commonplace in Europe, where drivers and teams negotiated fees in advance just to show up, Can-Am observed the “you have to earn your pay” philosophy. Race winners could do spectacularly well, but a diminishing scale of prizes extending down to even the last-place finishers made it worth their while to participate.

Big Stars

Although the imposing cars commanded attention, Can-Am was officially a driver’s championship. The idea was to grow a truly professional series out of traditionally amateur sports car racing. Indy drivers, NASCAR drivers, F1 drivers were all getting paid, so why not us, was the widespread feeling.

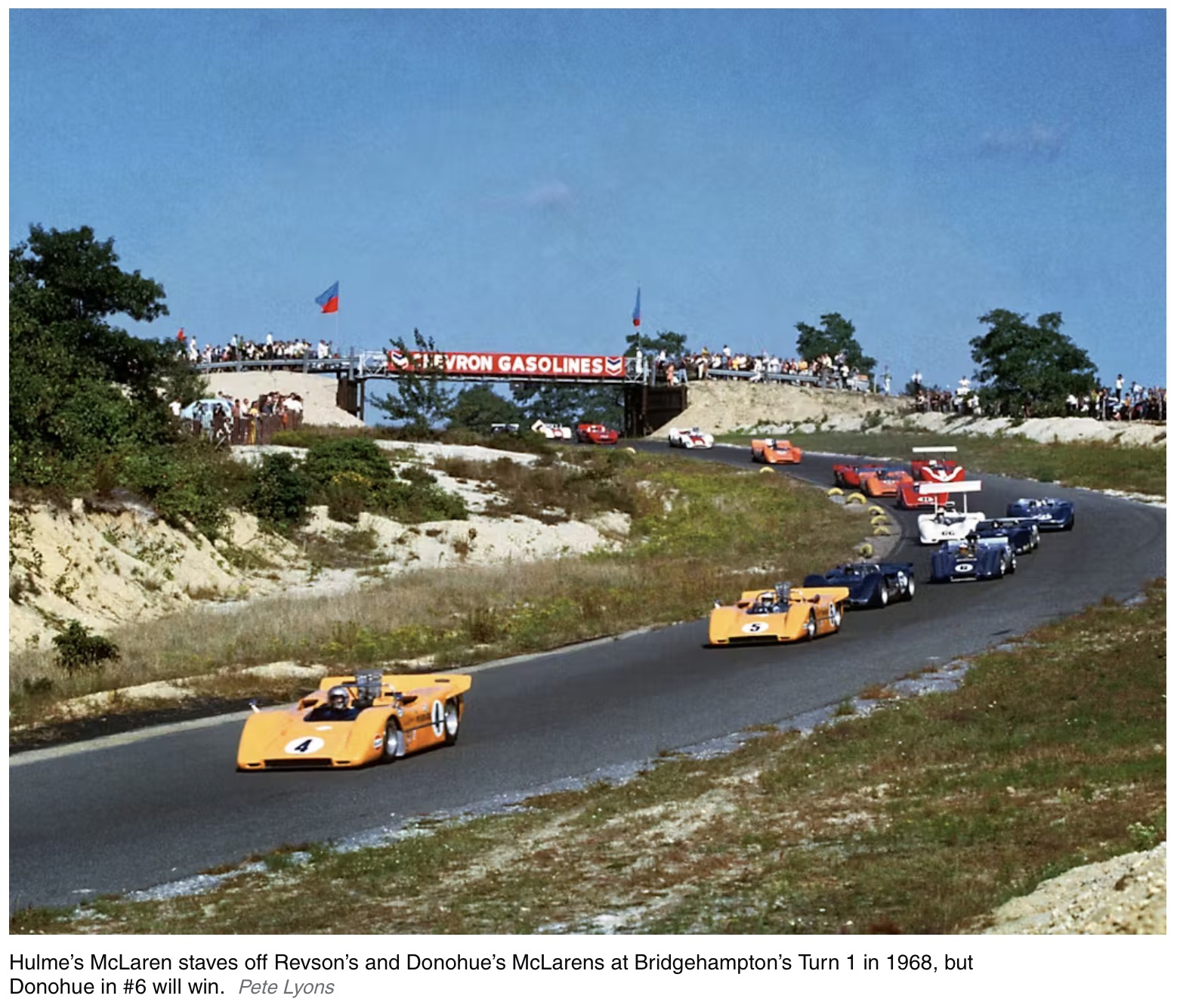

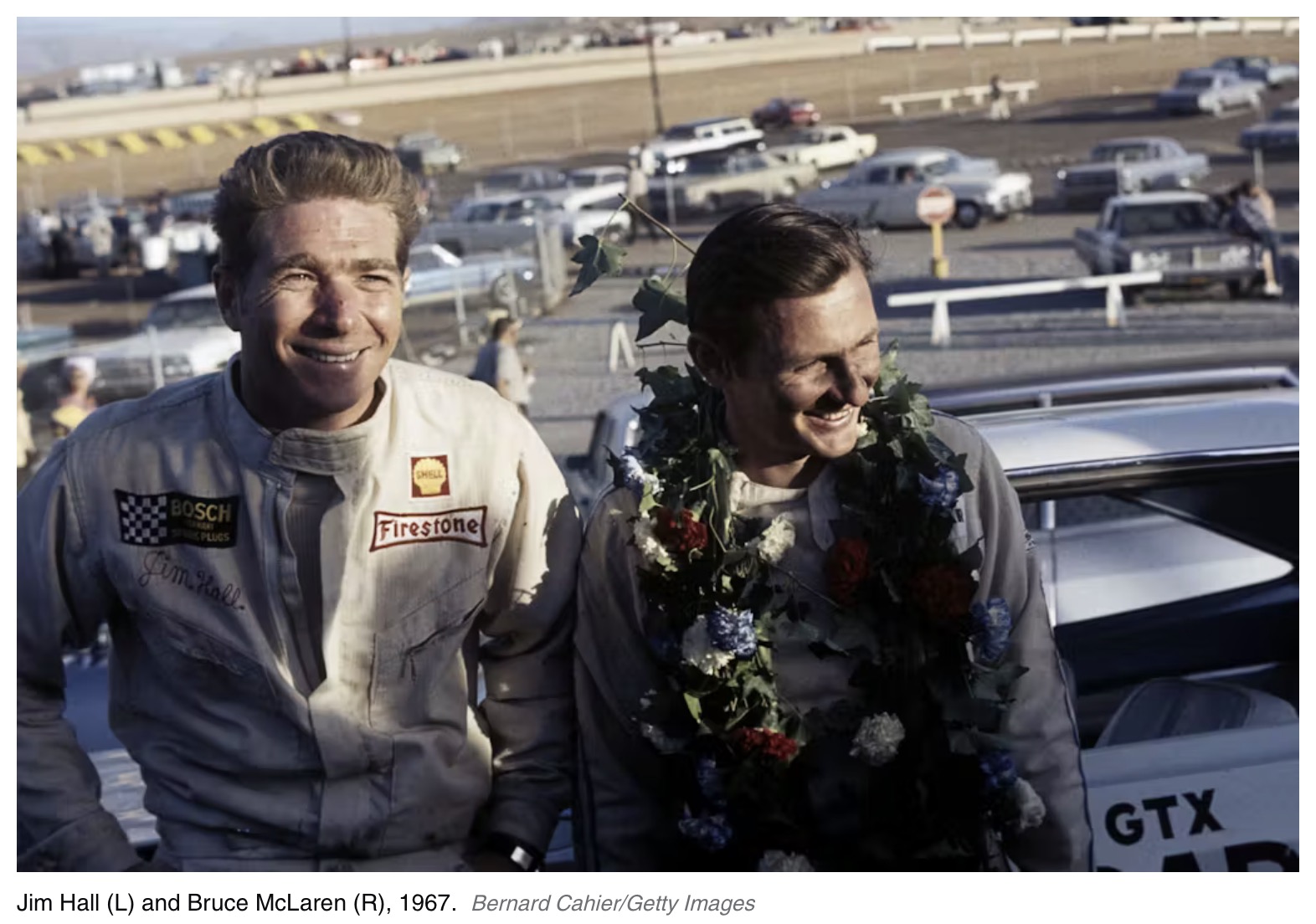

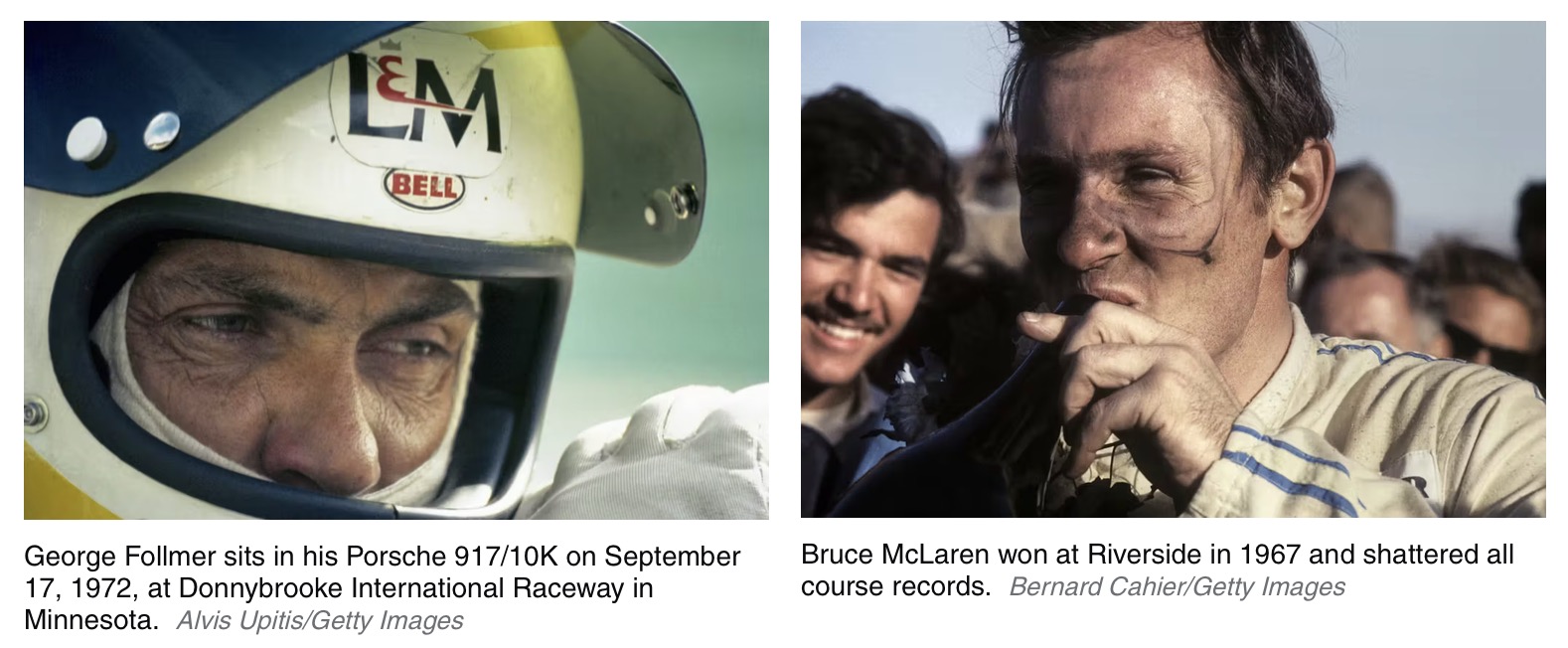

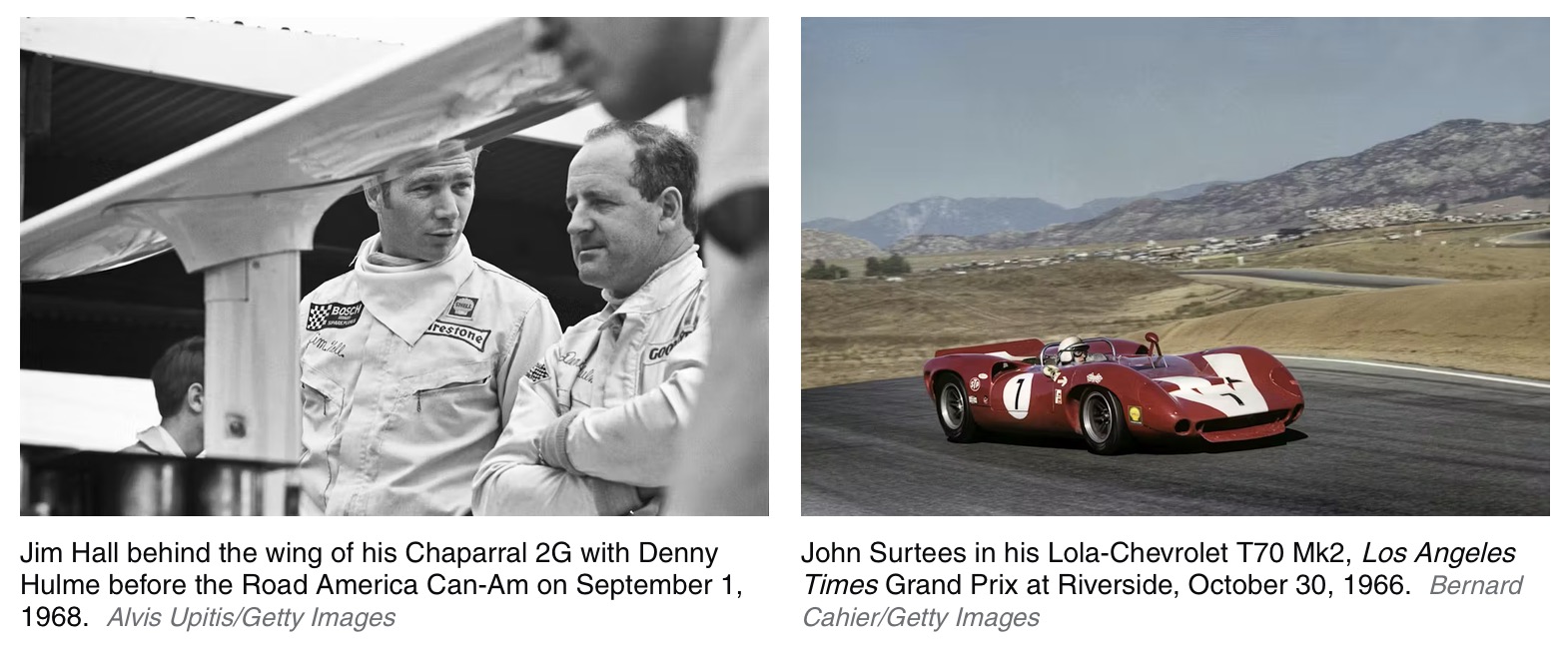

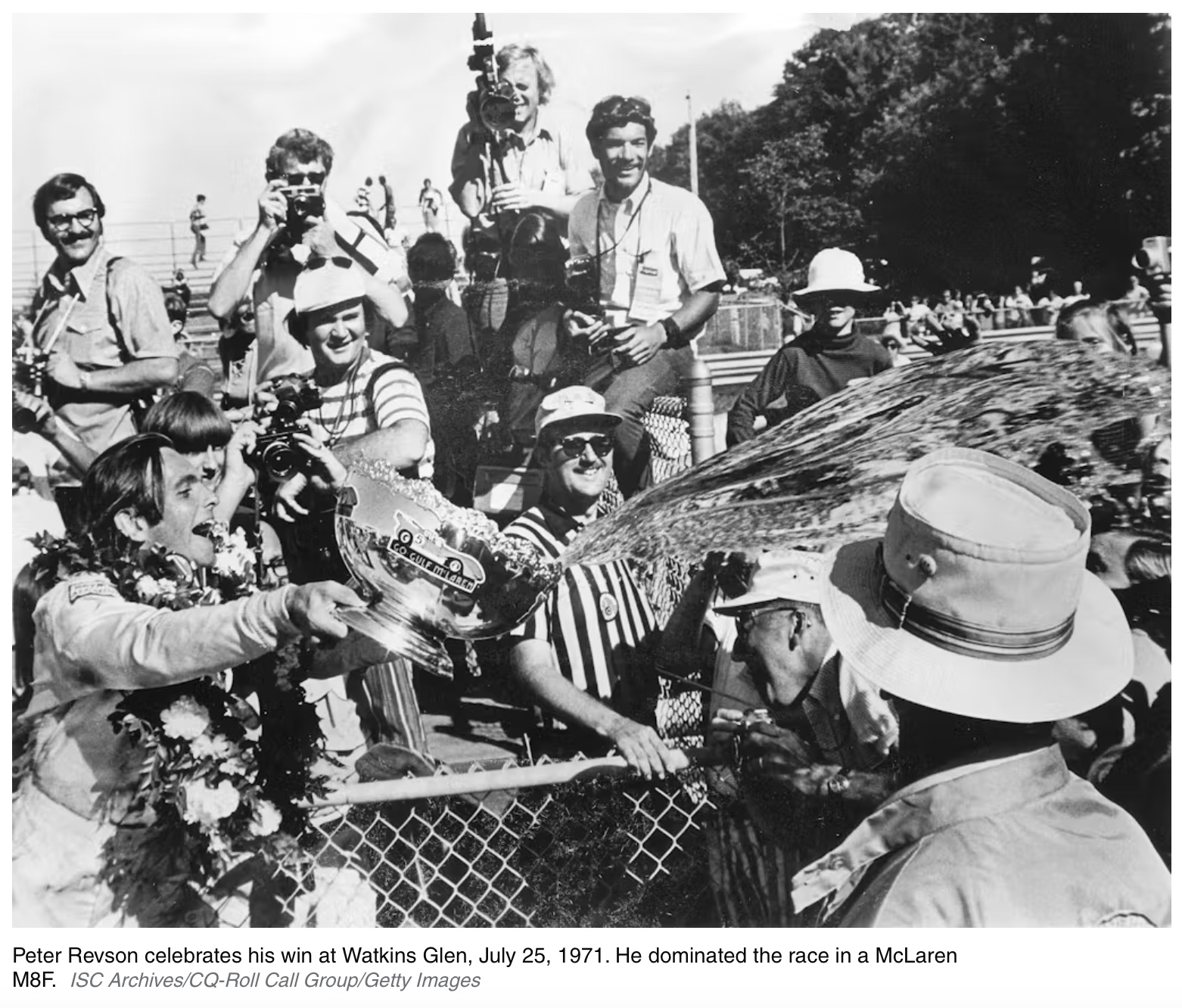

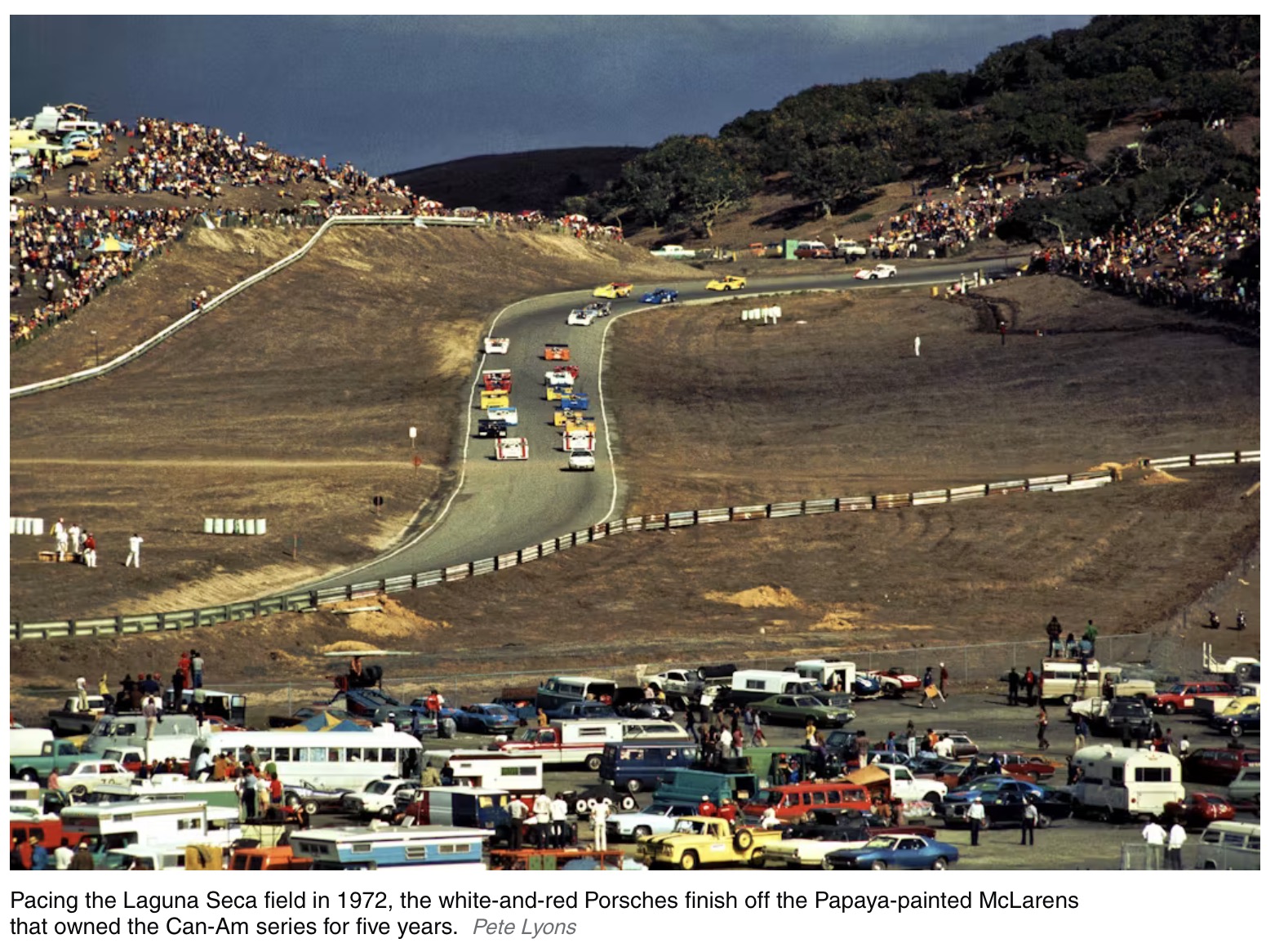

In the end, of course, the well-established professional road racers did best. The first title winner in 1966, Britain’s John Surtees, was also a world champion in F1 as well as grand prix motorcycle racing. Two-time series winner (1968 and 1970) Denny Hulme from New Zealand was another F1 champ. Trans-Am and Indianapolis 500 winner Mark Donohue earned himself a Can-Am trophy (1973), as did fellow Americans Peter Revson (1971) and George Follmer (1972). Can-Am’s final champion, Jackie Oliver, won for England again in 1974. All were F1 drivers as well, as was Bruce McLaren. “The Kiwi” from New Zealand, who built the cars that dominated Can-Am for five years straight (1967 to 1971), drove them to two series championships of his own (1967 and 1969), as well.

To win their titles, these men had to beat world-class talent such as Mario Andretti, Bob Bondurant, A.J. Foyt, Peter Gregg, Dan Gurney, Jim Hall, Hurley Haywood, James Hunt, Parnelli Jones, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, Sir Jackie Stewart, and more.

In the nine original Can-Am seasons, there were 71 races on 14 road courses across Canada and the U.S. Sixteen drivers won races, 115 scored championship points. Their best man? Denny Hulme, whose 22 victories far outstripped the nine apiece of McLaren and Donohue.

Big Cars

Race fans lucky enough to trek back and forth across the continent were constantly surprised by what we saw at the next track. Technology was evolving at dizzying speed. In the beginning, these full-bodied sports-racers had 500 horsepower and could beat F1 open-wheelers around two of the three grand prix circuits where they both appeared (Mosport in Ontario, and Watkins Glen, New York). In a few short, swift seasons, we saw 750-hp Chevrolet big-block V-8s and 1200-hp Porsche turbocharged 12-cylinders. Given enough room, these beasts could top 210 mph. Astounding numbers in those days.

Few, if any other kind of race cars, have evolved at such a pace, and it was all due to Can-Am’s extraordinarily welcoming attitude to experimentation. To be precise, Can-Am did have a rulebook, albeit a thin one. Chiefly, cars had to be recognizable as “sports cars,” meaning two-seaters with cockpit doors and bodywork covering all wheels. Of course, there were certain common safety requirements, such as seatbelts. But in most ways, the Can-Am car remained gloriously free of limitations.

Engine design and displacement were always open. Even the number of engines per car was up to the designers. So were key vehicle dimensions, configurations, and materials. Imaginative engineers could build a car as small or as large as they liked, in any shape, out of any material. Nor was there a specified minimum weight. Strange new aerodynamic appendages? Bring ’em on.

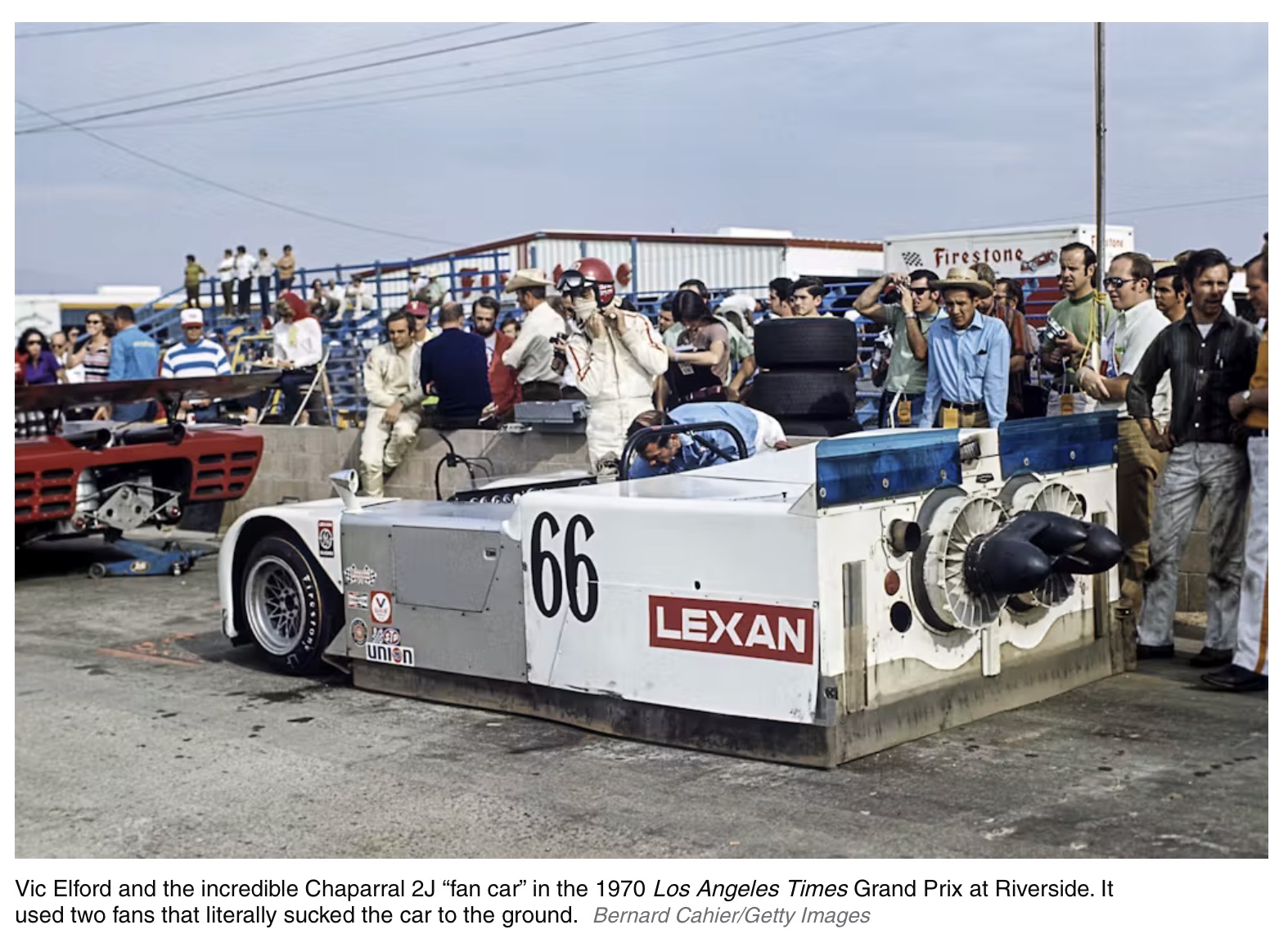

Firestone and Goodyear made tires as wide and grippy as they pleased. Wings on race cars, so common now, were first established in Can-Am, and so were aerodynamic ground effects-both introduced by manufacturer Chaparral. Turbochargers were first tamed for road racing in Can-Am; that was Porsche’s seminal contribution.

North America’s free-formula sports car racing was fertile soil not only for Chaparral, Jim Hall’s Texas hothouse of innovation, but also other radical concepts: Shadow’s startlingly low-slung “Tiny Tire” car by Trevor Harris, Bob McKee’s all-wheel-drive Armco vehicle with turbocharging and an air brake, and former Shelby Cobra man Jack Hoare’s bold attempt to power all four tires with four separate engines.

Beyond those marques, we saw so many more: BRM, Cooper, Ferrari, Ford, Lola, Lotus, March, McLaren, Porsche, each one different from every other. Can-Am was a traveling circus, bringing a menagerie of mechanical animals to race fans all across North America. There was always something marvelous to see at a Can-Am race, both in the paddock and, especially, at speed on the track.

In 1973, Mark Donohue drove the Porsche 917 /30 to victory at the Can-Am Los Angeles Times Grand Prix at Riverside. The 917 made more than 1500 horsepower.Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

From 1970 on, however, more and more regulations were imposed. Restrictions on aerodynamic experimentation induced Jim Hall to pull Chaparral out of Can-Am. “It’s no fun anymore,” the great driver-engineer remarked to this writer at the time. The remaining bigblock beasts, the Lolas and McLarens and Shadows, were still loud and fast and frightening, but something was missing: the sense of liberation. Once unique, Can-Am cars had become conventional.

There were other reasons for the decline. The costs to develop cars became prohibitive. The series lost its crucial sponsor, Johnson Wax, choking off prize money that most teams relied on. Once-massive spectator counts dwindled, so track owners lost interest as well.

Alas, as with 1969’s wild-and-free festival of music in the mud, Can-Am’s noble experiment in “no-rules racing” did not go on forever. But for a time, there was nothing like it, with the cars pitching and heeling and sliding, the driver’s work at the wheel fully visible in those open cockpits. You could see something tremendous was going on. And the thunderous noise! You could feel it in your boots. Watching a big-block Can-Am car slam by with its dander up was a duck below-the-guardrail experience.

Woodstock on Wheels.

Report by Pete Lyons for hagerty.com