Imagine you’re Lance Reventlow. You’re young, dangerously handsome, unimaginably wealthy. Your mother is Barbara Hutton, the original “poor little rich girl,” heiress to the vast Woolworth fortune. You haven’t seen your father, an authoritarian Danish count with the movie- villain name Court Haugwitz-Hardenberg Reventlow, since he lost a sordid public custody battle for you years ago. Instead, you’re treated like a favorite son by Cary Grant, who is another one of your mother’s many exes. (She would go on to have a grand total of seven.)

You live in a posh house in the Hollywood Hills with a proper British manservant named Dudley. You date Hollywood starlets and drive a Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing that you bought on the spur of the moment. You make the rounds of Los Angeles with a group of other rich kids known collectively as the Alpaca Rat Pack. But this is the 1950s, so your antics don’t involve hard drugs or dive bars, and most nights end at the Luau, an upscale Polynesian restaurant where a large table, Bar 5, is always reserved for you no matter how crowded the place gets.

You’re an instrument-rated pilot and world-class skier, but cars are your passion—the way they look, the way they work, the way they drive. Inevitably, you gravitate to racing. You start in Southern California in a 300SL, not your street car but an even more exotic sleeper with a rare aluminum body. You’re not a natural, but you’re competent, and you want to get better. In 1957, you travel to Europe with your racing sensei, Warren Olson, the Cooper distributor in L.A., and you tow a Formula 2 Cooper T43 from country to country with a stately 1936 Rolls-Royce that your mother bought to mark the year you were born.

The European adventure turns out to be a bad trip. Most of your race entries get rejected, and at Snetterton, when you finally get to compete, you catapult out of the cockpit after flipping your sweet little Maserati 200S. By this time, you’ve been joined by your best friend, Bruce Kessler. Other members of the Alpaca Rat Pack call the two of you Death and Destruction. Kessler is wicked fast behind the wheel; the previous year, he’d won the 500cc Club of America Championship. You and he have a dream—to shoehorn a Chevy V-8 inside a state-of-the-art sports car chassis and terrorize the stuffy road-racing set.

You make pilgrimages to several English race shops—Lotus, Cooper, BRM. Today, you find yourself in Cambridge, hunting for a garage tucked among Victorian row houses near Abbey Road. Here, a constructor named Brian Lister builds the Jaguar-powered cars that are dominating the British sports car racing scene. Lister himself gives you the grand tour while you pepper him with technical questions. Kessler is totally impressed. You’re not. “That thing’s a piece of junk,” you say after leaving the shop. “We could build a better chassis than that.”

“Right,” Kessler says, humoring you. “We could build a better chassis than that.”

“Let’s build one,” you insist, dead serious.

Kessler shrugs. “Right. Let’s build one.”

So you do. And you name it the Scarab.

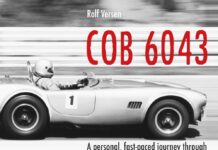

A generation ago, Scarabs were the stuff of legend, and the mere mention of the marque inspired expressions of awe from those lucky enough to have seen them thundering around the track. These days, they’re overshadowed by the Cunninghams that preceded them and the Cobras that followed—just as Reventlow seems diminished, standing as he does between the noblesse oblige of Briggs Cunningham and the larger-than-life mythology of Carroll Shelby. But the Scarab was the most fearsome sports racer of its day, and even now, so many decades later, it’s still the apotheosis of the American road-racing special.

In 1958, the Scarabs eviscerated the competition, steam-rolling everything from sleek Jags and elegant Astons to one-off Maseratis and factory Ferraris. With nothing left to prove, Reventlow sold two of the sports cars while they were still virtually unbeatable and embarked on a quixotic quest to build the first American Formula 1 car. Unlike the Yankee F1 hopefuls that followed, the Scarab was the only one designed, engineered, fabricated, and assembled entirely in the United States. Alas, it was also the last F1 car to be developed with a front-engine design, and its archaic architecture doomed it to a fate as a glorious failure.

In 1962, Reventlow shut down his company and quit racing cold turkey. But the cars took on lives of their own, continuing to win pro races in other hands until 1964. Seven of Reventlow’s eight creations survive, but don’t plan on adding one to your garage. Most of them are owned by major-league collectors and vintage-raced only at A-list venues. They rarely go on sale, and when they do, they command price tags starting in the seven figures.

Like all works of art, no two Scarabs are exactly alike. But each car tells the same story, and that’s the fairy-tale life of Lance Reventlow.

Road racing was like the Wild West during the formative years after World War II. There were laws, but they weren’t strictly enforced; there were hierarchies, but they were constantly being upended. It was an era that rewarded audacity, both on and off the track. Anything went, and everything was measured by a single standard—speed. Fast was good. Slow was not. Pedigree? Who cared?

The sports car revolution was fueled primarily by men who’d returned from the war with money, energy, and a thirst for adventure. The West Coast took the lead because it was home to the hot-rodders who’d honed their skills on the dry lakes of the Mojave Desert in the 1930s and were looking for new challenges. A lot of them ended up working on Indy cars. Others found jobs in the aerospace industry. Reventlow figured he could tap into this fertile vein of raw talent and hire the best and brightest to create a car unlike anything ever seen before.

Reventlow Automobiles was incorporated in 1957. Warren Olson was hired to manage the team. On August 20, he cut RAI’s first check, $61.99 for a frame table, and earmarked three bays of his shop in West Hollywood for Reventlow’s Scarabs. Over the next few years, with Barbara Hutton providing the funding, Olson assembled a hall-of-fame stable of the premier race car craftsmen in Southern California.

It included Dick Troutman and Tom Barnes, better known as Troutman & Barnes, for their complementary welding and fabrication skills; taciturn ex-paratrooper Chuck Daigh, mechanic par excellence and ace driver of the flathead-powered Troutman-Barnes Special; engine wizards Jim Travers and Frank Coon, the founders of Traco, the best-known race motor shop in the country; Phil Remington, the legendary jack-of-all-trades who would become the centerpiece of the Ford GT program and a mainstay at Dan Gurney’s All American Racers; Emil Diedt, the master metal shaper who built the iconic Indy-winning Blue Crown Spark Plug Specials; Leo Goossen, the power behind the throne occupied by Harry Arminius Miller and himself a legitimate engineering genius; and Kenneth Howard, the pinstriping artiste better known as Von Dutch, who fashioned the Scarab’s signature blue metal-flake paint scheme.

“We’d leave work about 6 o’clock,” Remington recalled, “and [Von Dutch] would come in with a couple of six-packs of beer and his painting equipment, and he’d mask everything and shoot it and stripe it and work until whenever it took to finish. We’d come in in the morning, and there’d be paper and beer cans and crap all over the place. We’d peel the tape off, and that was it—perfect. He was a real artist, that guy, but strange.”

The car was conventional technically but impeccably built. The tube-frame chrome-moly chassis generally followed the plans sketched by Ken Miles—yes, that Ken Miles. Virtually all the components were made in the States. Corvette gearbox. Ford drum brakes. Halibrand quick-change rear end. Firestone Super Sports. Halibrand mag wheels with Indy-style knockoffs. And most important of all, the engine, which gave the car its signature growl.

Although the Scarab wasn’t the first car to use the small-block Chevy, it was the one that unlocked its potential. The powerplant was so good, in fact, that RAI barely modified it. “We couldn’t buy a whole engine,” Daigh recalled. “We bought the pieces and built our own. And in those days, you didn’t open a catalog and go buy roller rockers and all those things because they just didn’t exist. In fact, I have to laugh. When we put the first car together, it had stock valve springs, stock rocker arms, stock pushrods and so on, and that’s how we raced it.”

Eventually, Daigh settled on an engine bored and stroked to displace 339 cubic inches. Fitted with Hilborn fuel injection, a Vertex magneto, and Racer Brown cams, it made 365 horsepower at 6000 rpm and 370 lb-ft of torque at 4500. In an uphill track test instrumented by Road & Track, the car went 0–60 in 4.2 seconds and knocked out a quarter-mile in 12.2 seconds at 120 mph. With a 3:31 gear, Daigh said, he could exceed 175 mph.

The bodywork was almost an afterthought, so its design was entrusted to an 18-year-old student at Art Center College named Chuck Pelly. He drew a single sketch on black paper, and then the car was laid out directly on plywood forms. “The only tools involved in the design of the body were two carpenter pencils and a 4-foot square,” Pelly recalls. “We didn’t even have plastic curves. We just bent pieces of wood and drew right on the plywood. Then the plywood was cut out along the pencil lines, so it was essentially a disposable drawing. The drawing became the buck. It didn’t take very long, maybe two and a half weeks. As I remember, my total fee was about $200.”

The car was a rocket ship out of the box. At the first test, at Willow Springs on January 16, 1958, Daigh broke the lap record. A week later, he went four seconds faster. A month after that, during the Scarab’s official debut at an SCCA regional in Phoenix, Kessler shattered the lap record by six seconds before lightly pranging the front end. After Kessler had another minor off during a test at Riverside, Reventlow had Diedt recontour the front end, tighten up the grille, and camouflage the roll bar with a headrest fairing. Diedt’s handiwork became the definitive Scarab shape—brawny rather than voluptuous, a more athletic version of the Ferrari 750 Monza. It was Maranello by way of the Sunset Strip.

Reventlow scored the marque’s first win at Santa Barbara in May, outrunning Max Balchowsky’s Old Yeller and Richie Ginther in a Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa. A second Scarab was built for Daigh, whom Reventlow designated as the number one driver with orders never to ease up to let him win. For the rest of the year, the two cars crisscrossed the country atop a right-hand-drive, ex-Maserati transporter and waxed all comers. Scarabs won every race they finished and set lap records at every track they visited.

The Scarabs peaked at Riverside during the USAC-sanctioned U.S. Grand Prix for Sports Cars, then the most lucrative road race in the world. The pre-race favorite was reigning Le Mans champ Phil Hill, fresh off a third-place finish at Monza in his F1 debut for Ferrari. At Riverside, he was driving a factory-prepped Ferrari 412 S with a fire-breathing 4.1-liter V-12. It was the fastest Ferrari sports car yet. But it was no match for the Scarab, and Daigh breezed home first. “There wasn’t any car in the world that I couldn’t beat with that Scarab,” Daigh said.

The season ended in the Bahamas with run-what-you-brung races during Nassau Speed Week. Reventlow cantered to a win in the preliminary Governor’s Cup, and he and Daigh co-drove to victory in the Nassau Trophy feature. It was the last race Reventlow ever won.

Back when he was 14, a judge let Reventlow decide whether he wanted to continue living with his father in Newport, Rhode Island, or with his mother, who was by then remarried to an impoverished Russian prince named Igor Nikolayevich Troubetzkoy, winner of the Targa Florio in 1948. Reventlow despised both of his parents, but while his father was a Germanic disciplinarian, his mother had a more laissez-faire approach to parenting. She offered to set him up in a rental house in the Hollywood Hills overlooking Universal Studios with a butler and a housekeeper-cum-nanny he called Sister. Not a tough decision. After graduating from a boarding school for affluent asthmatics, he spent two months at Pomona College before dropping out and settling into life in Southern California.

Reventlow immediately looked up his old high school bud, Bruce Kessler, and found him working as a parts chaser for Warren Olson, the Cooper distributor who would become RAI’s team manager. The two young men were simpatico; they both came from families of privilege and shared a fascination with fast cars. Kessler’s mother virtually adopted Reventlow and Bruce plugged him into a coterie of other young scions and children of celebrities. Some of them, like Natalie Wood, were celebrities themselves. Reventlow cruised around town in his exotic Gullwing. When gawkers asked him what it was, he told them that it was a Goldberg, made in Israel.

Despite his truncated education, Reventlow was witty, well-read, personable, and extremely bright. His tastes were cosmopolitan—haute cuisine, classical music, art and design, polo. But the party scene bored him. “Hollywood society,” he said, “is like going down a sewer in a glass-bottom boat.” He was just as comfortable with proles as patricians. One night, after a group of outlaw bikers started giving him grief about his hoity-toity Mercedes, he defused the tension by engaging them in a confab about the technical details of their motorcycles, and they left as friends.

The rich kid didn’t want to be known as a spoiled rich kid. “You were born with brown eyes,” he told people. “I was born with money. It just makes life convenient.” Being wealthy meant he could pay for things, whether it was a twin-engine Cessna 310 or developing a race car from scratch. Money also allowed Reventlow to be generous. While driving back from a drag race in Bakersfield in the Gullwing with his friend Raoul “Sonny” Balcaen, who would later work as a mechanic at RAI and restore a Bugatti for Reventlow, Balcaen offered to throw in for the gas money. Reventlow pointed to a Woolworth five-and-dime store they happened to be passing and told him, “There’s the old bastard who’s buying our gas.”

Reventlow outgrew the party pad in the Hollywood Hills and commissioned a mansion in Beverly Hills whose midcentury modern design included a pool that bled into the living room. His playmates dubbed it Camp Climax. He continued to date starlets. When British actress Dawn Adams dumped him for an Italian prince and asked why he never gave her a keepsake of their friendship, he had a 50-pound bag of Bandini fertilizer delivered to her apartment. Eventually, Reventlow focused his attention on rising star Jill St. John, who supposedly had an IQ of 162. “I had great difficulty in sustaining a conversation with an actress,” he told a gossip columnist writing a fawning profile, “until I met Jill St. John.”

He was used to getting his way, and when he didn’t, the results weren’t pretty. At the shop, Jim Travers led a delegation of RAI employees who threatened to quit if he didn’t stop acting like a crybaby. Later, Reventlow suffered an epic, embarrassingly public meltdown at Riverside when USAC officials wouldn’t let his hastily repaired car leave the pits. The press coverage was brutal, but no surprise there. Even during an age before TMZ and social media, people like Reventlow had giant targets on their backs, and haters gonna hate. But his mother taught him well: Never explain, never complain.

The critics inspired Reventlow. When they said he was just a dilettante, he created the greatest sports racer America had ever seen. Then, when they griped that all he’d done was outspend the competition, he raised the stakes and took on the biggest challenge in racing: scratch-building an all-American Formula 1 car.

In 1959, Formula 1 received so little attention in the United States that races might as well have been run on the moon. The rear-engine revolution that had overwhelmed Europe was barely a rumor on this side of the Atlantic, so when RAI got to work on an F1 car, it was only natural that the motor was placed in front of the driver, where God and Enzo Ferrari intended. Twenty-three-year-old aviation engineer Marshall Whitfield was hired to design the chassis, even though he had no race car design experience. He was given two directives: Make it American, and make it quickly. You couldn’t have written a more effective recipe for disaster.

The fundamental problem was that the only purebred American race motor eligible to compete in the 2.5-liter formula was the venerable Offenhauser, which dated back to the early 1930s (and which would race at Indy until 1980). Unfortunately, the powerband was too narrow for road racing. On the other hand, one of the principal architects of the Offy, Leo Goossen, was available. And Reventlow thought he had access to the proverbial unfair advantage.

A few years earlier, Mercedes had loaned one of its 300 SLR endurance racers to the Henry Ford Museum. Ford Motor Company saw an opportunity to unravel the mysteries of the engine’s exotic desmodromic valvetrain, which used a pair of cams rather than springs to directly close each valve, thereby eliminating overrevs and encouraging better breathing. Ford hired Travers and Coon to surreptitiously disassemble the engine to study the desmo gear. The technology was impractical for street cars. But Reventlow was convinced the valvetrain would be his secret weapon on the track.

Goossen designed a twin-cam, twin-plug four-cylinder engine with an aluminum block and head. Even with the trick desmo gear, it made only 218 horsepower—this when the Coventry-Climax was rated at 240 ponies, the BRM at 270, and the Ferrari closer to 280. Decades later, Daigh came across a copy of Goossen’s original drawings and discovered that the valve clearances had been set improperly. When he rebuilt one of the old motors to Goossen’s specs, it produced 267 horses, and he figured 280 would have been achievable.

But lack of grunt was only one of RAI’s problems. The car also didn’t turn or stop worth a damn. The lone advantage of being the last front-engine Formula 1 car was that it was the loveliest of the breed, with a long, low hood line and a sensuously rounded rear end. When the two Scarabs showed up in the pits at Monaco in 1960, they looked like a million bucks. But it was all show and no go. Neither car came within eight seconds of qualifying. “Before we went to Europe, we had convinced ourselves that those guys were lying, that they couldn’t get all that much power out of their engines,” Daigh said. “When we got to Monte Carlo, I was devastated.”

The team’s fortunes never improved. Although Daigh qualified 15th at Zandvoort, Reventlow withdrew both cars in a hissy fit after a dispute about starting money. Both Scarabs DNF’d at Spa with engine failures. At Reims, the engines puked before the race even started. RAI bailed after this fiasco. The F1 car raced only one more time, with Daigh finishing a dispiriting 10th at Riverside, five laps behind the leader. This was the final grand prix of the 2.5-liter formula. And it was, in many ways, the end of the Scarab dream.

Working with a reduced staff, RAI built two rear-engine cars—a sports car and a single-seater—after the F1 debacle. But in 1962, Reventlow’s mother cut off the money spigot, and he was given 30 days to dismantle what was left of the company. Fittingly, Reventlow didn’t even bother to finish his last race. Mired in midpack in the rain at Nassau, he splashed into the pits, climbed out of the cockpit, and told Augie Pabst, “I don’t want to drive it. You drive it.”

But the Scarabs lived on after RAI’s demise. The front-engine sports cars won tons of races in Nickey Nouse and Meister Bräuser liveries, and A.J. Foyt and Walt Hansgen scored victories in the rear-engine car that Reventlow had abandoned at Nassau. Reventlow kept only one Scarab—the original prototype, which Balcaen painstakingly converted into a street car. He ended up selling it for pennies on the dollar, and by the time he died, his automotive needs were being satisfied by a Porsche 911E and a Volkswagen Beetle.

Reventlow’s marriage to Jill St. John imploded about the same time RAI did. In 1964, a year after the divorce, he married Cheryl Holdridge, a 20-year-old former Mouseketeer better known as Wally’s girlfriend on Leave It to Beaver. After that, he was content to pass the time surfing and sailing in Hawaii, skiing in Aspen, and listening to Mozart on his state-of-the-art hi-fi. He never raced again. Motorsports was a chapter in a book he no longer opened.

On July 24, 1972, Reventlow climbed into the back seat of a single-engine Cessna 206 along with two real estate agents and a freshly minted pilot. He was scouting for land near Aspen to convert into a ski run. Shortly after takeoff, the pilot was trapped in a box canyon when a summer squall hit. The airplane crash-landed in a tree. There were no survivors. Reventlow was 36.

Thirty years ago, while conducting research for a book about the Scarab, I talked to dozens of Reventlow’s friends and acquaintances. So far as I know, he never told any of them why he turned his back on the sport that had produced so many of his most satisfying triumphs and gut-wrenching disappointments. To me, it sounded like a love affair gone so disastrously wrong that it was too painful to revisit. Or maybe he realized that, after enjoying the view from the top of the mountain, he’d never be satisfied with a less lofty vantage point.

It’s easy to look at Reventlow’s last years and say he didn’t do much with the rest of his life. But in creating the Scarabs, he did one great thing, and that’s a lot more than most people can say, no matter how much money they have.

Report by Preston Lerner for hagerty.com