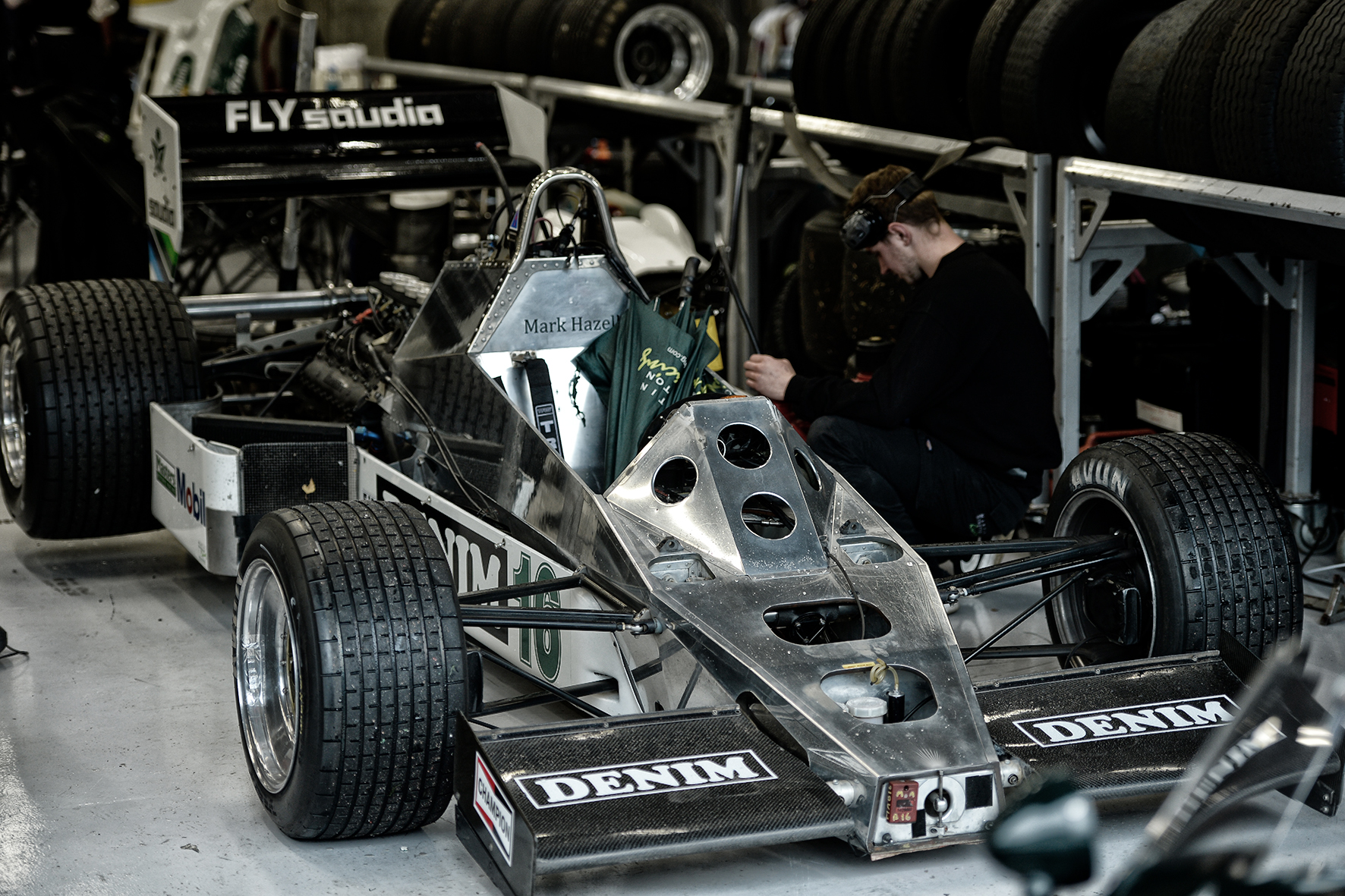

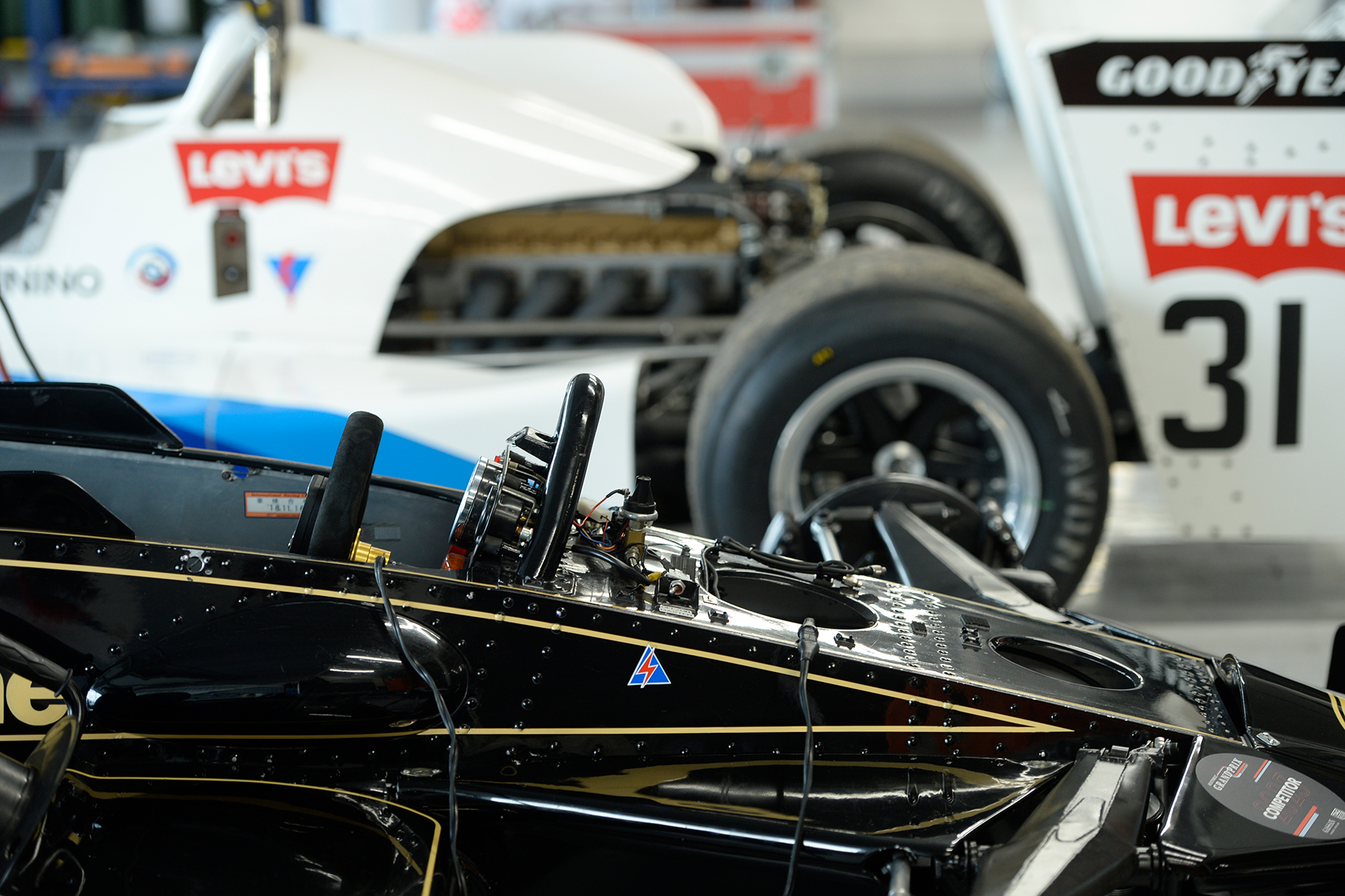

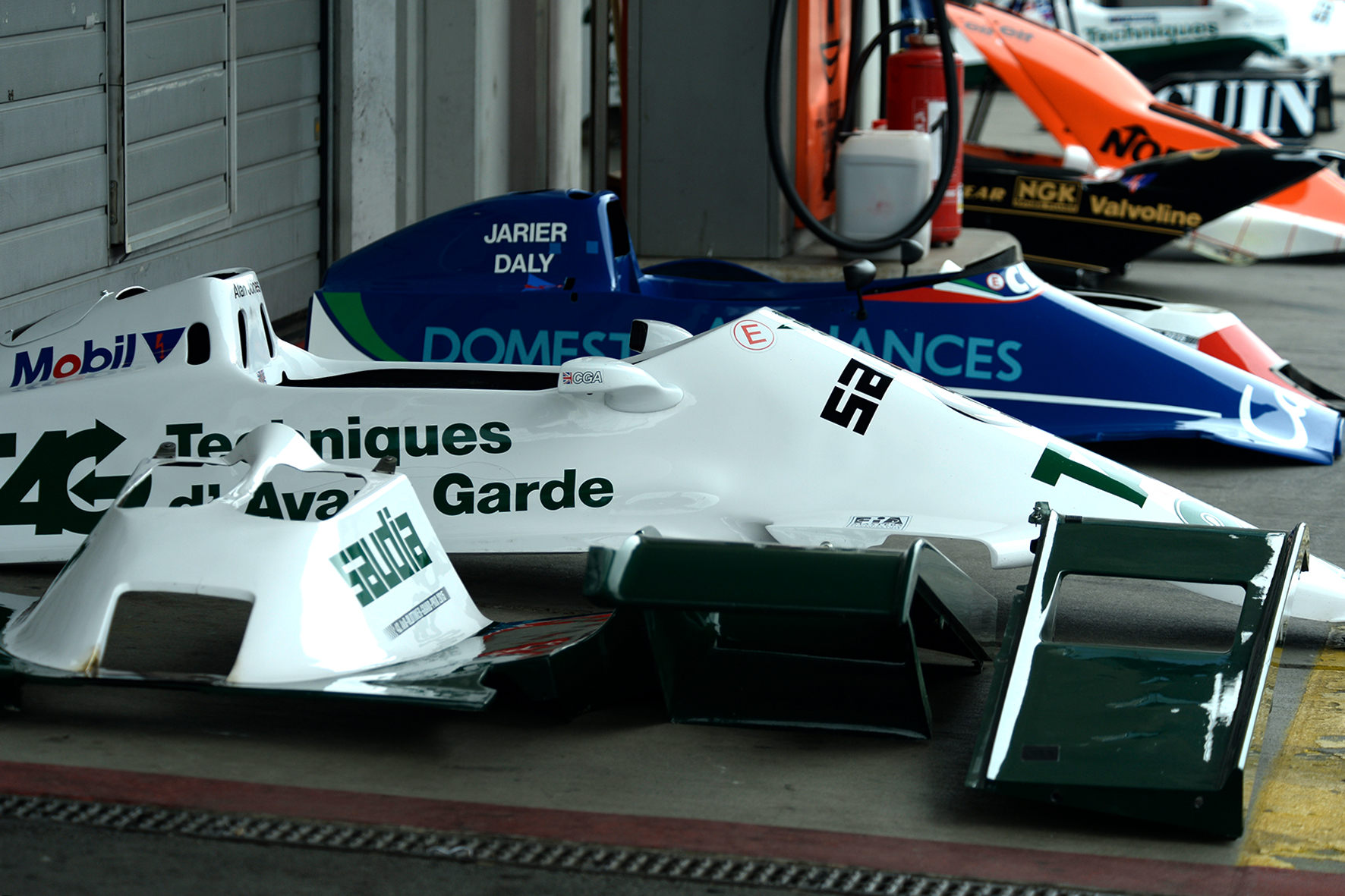

Nowhere else can visitors and photographers get as close to Formula One racing cars as at historic motorsport events. When the drivers and their racing cars are not out on the track looking for seconds, they are in the pits being prepared, serviced or, in the worst case, repaired.

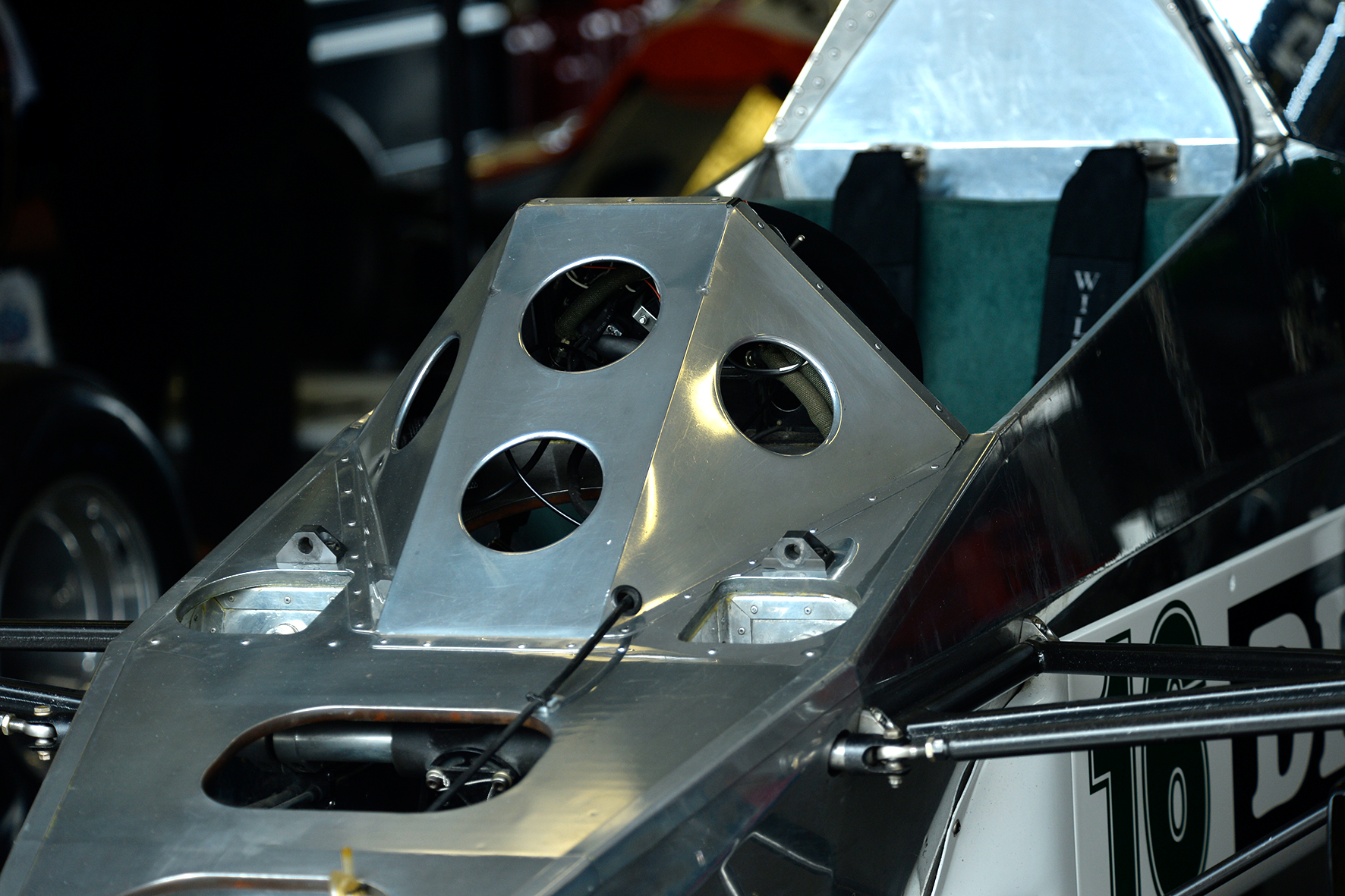

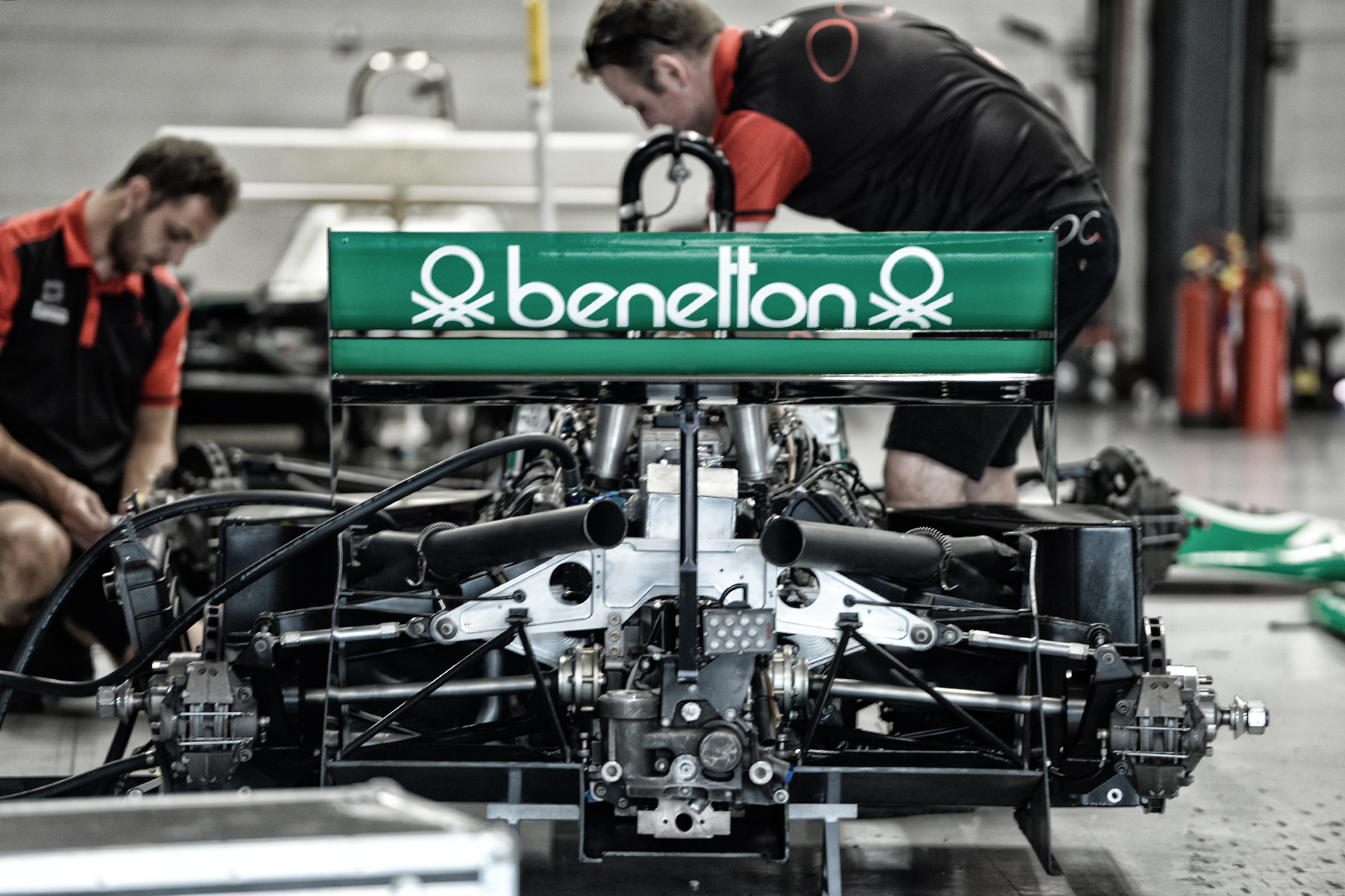

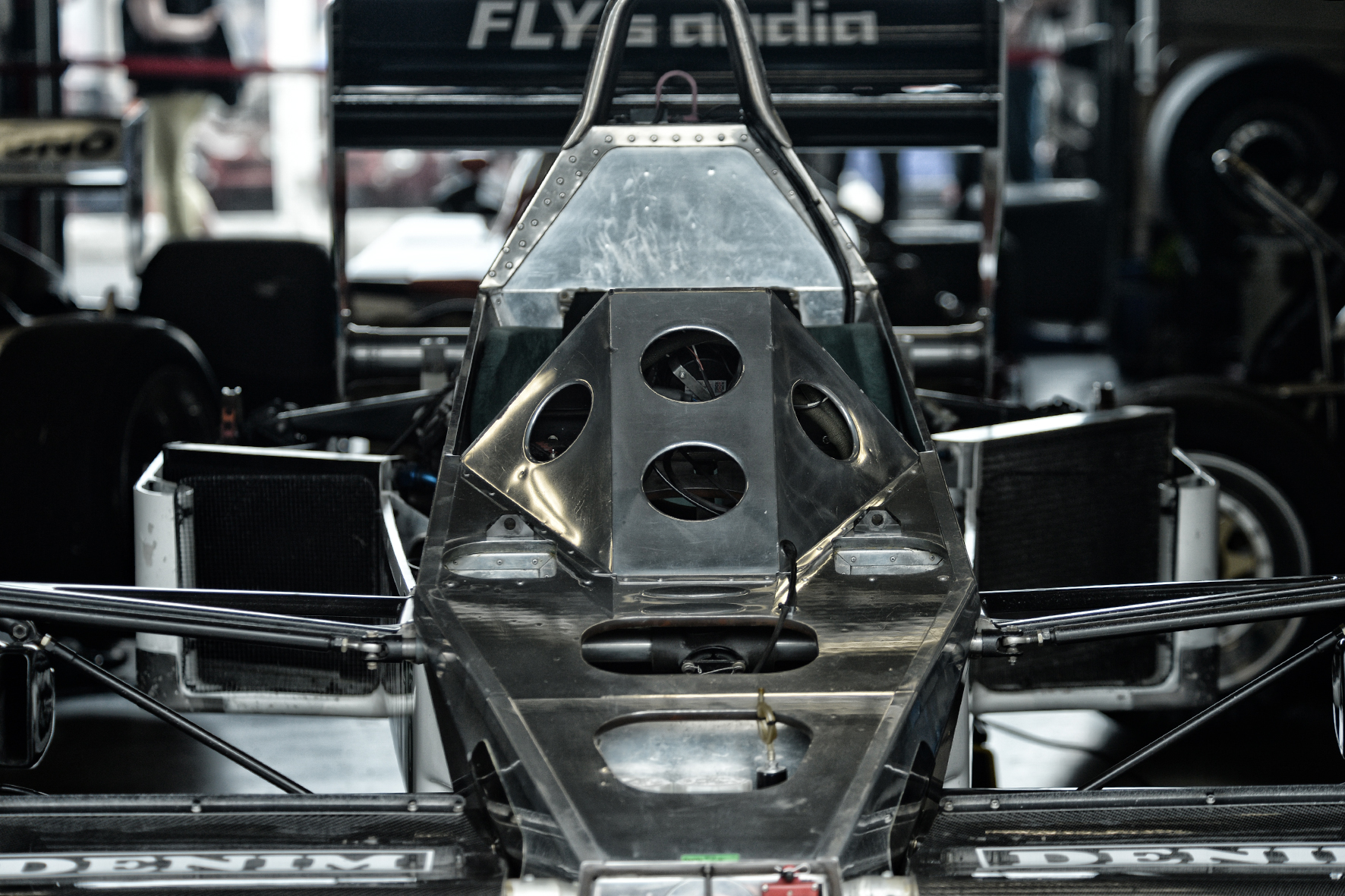

During this work, it is of course necessary to remove the individual body parts so that the view of every little design detail is unobstructed. Of course, such insights are not possible in the current Formula 1, where everything is kept a very big secret and the fear of espionage is omnipresent. Because then as now, the smallest technical tricks, the most unusual aerodynamic tricks determine the success or failure of a Formula 1 racing car.

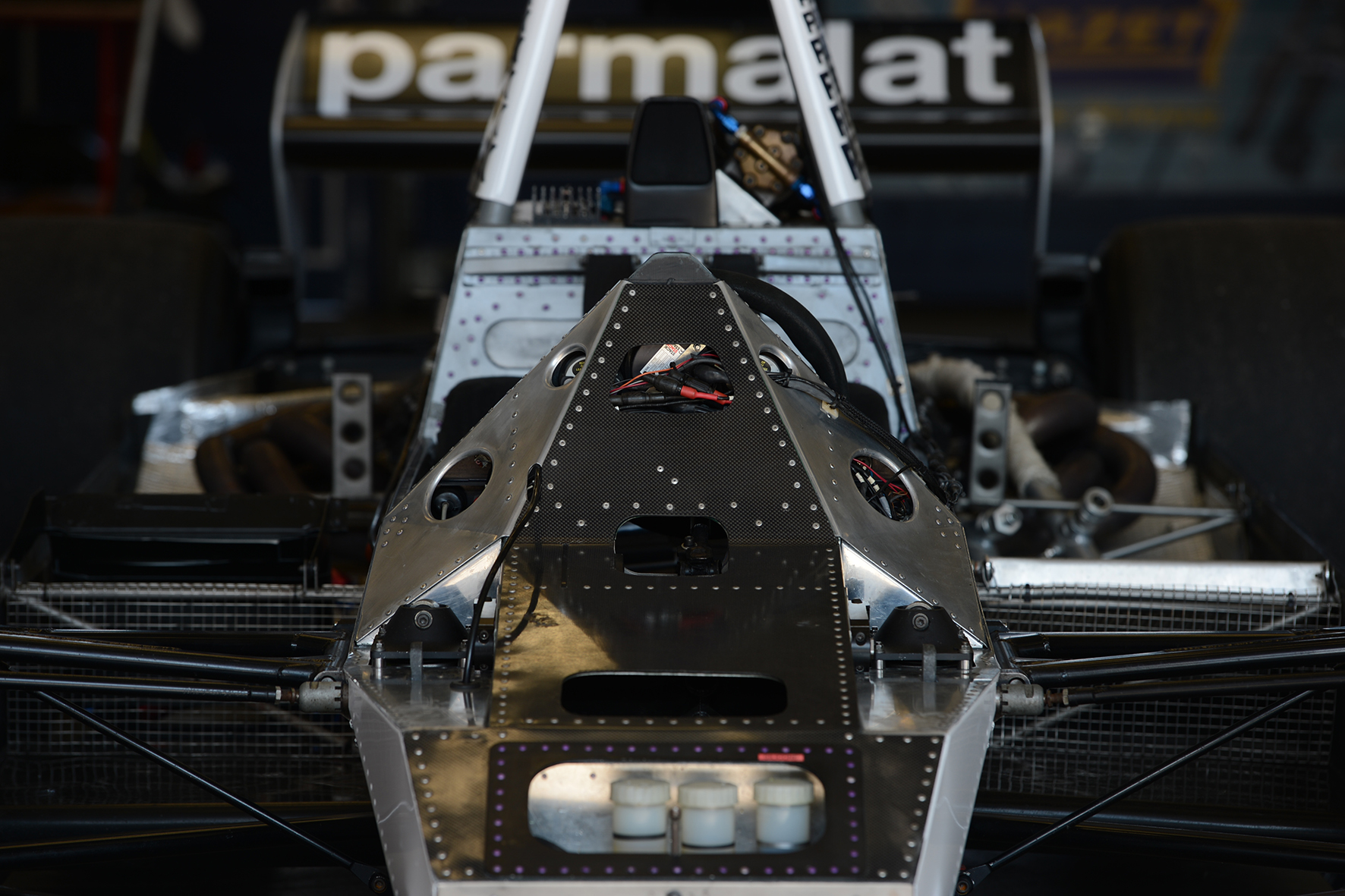

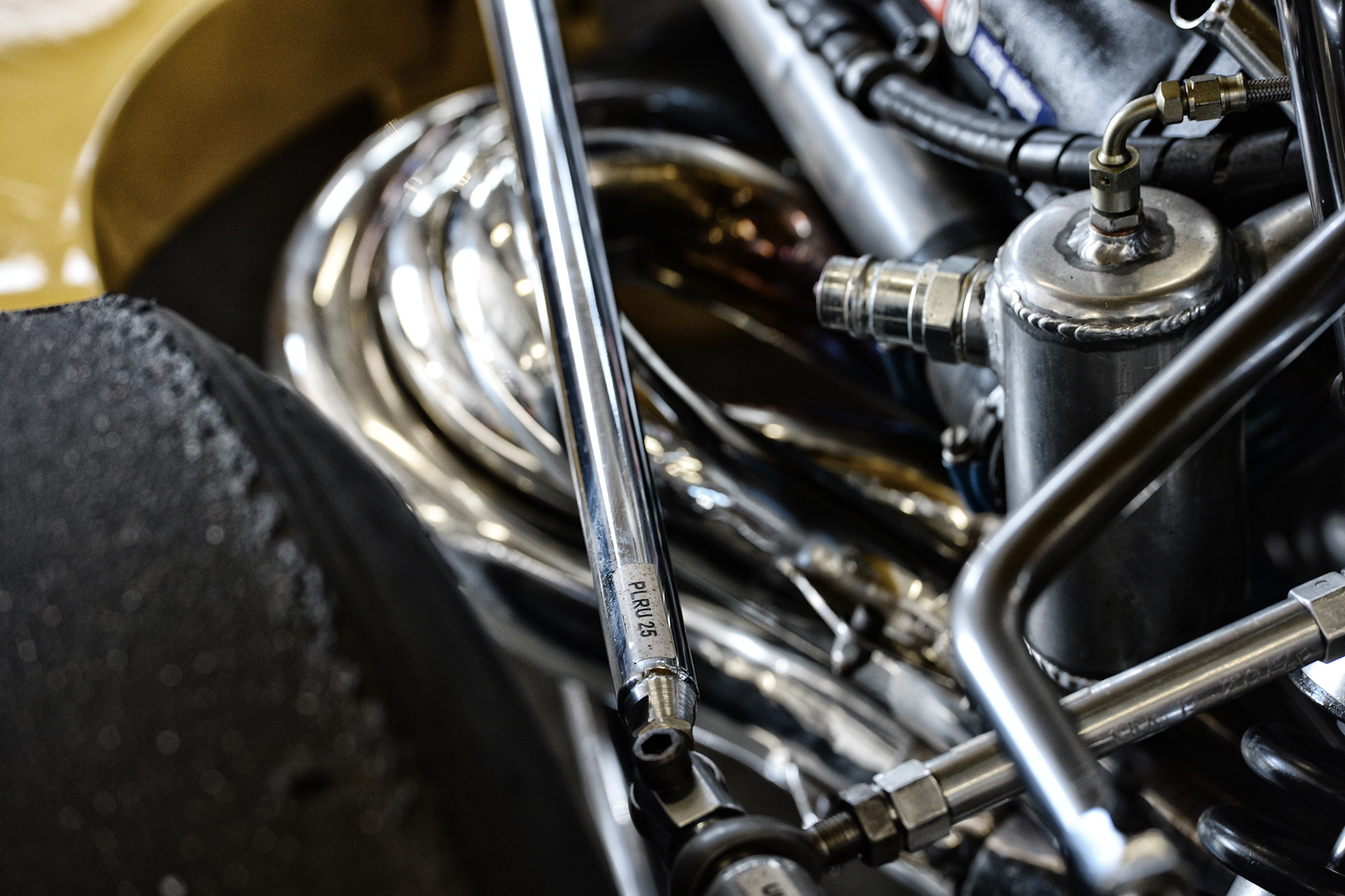

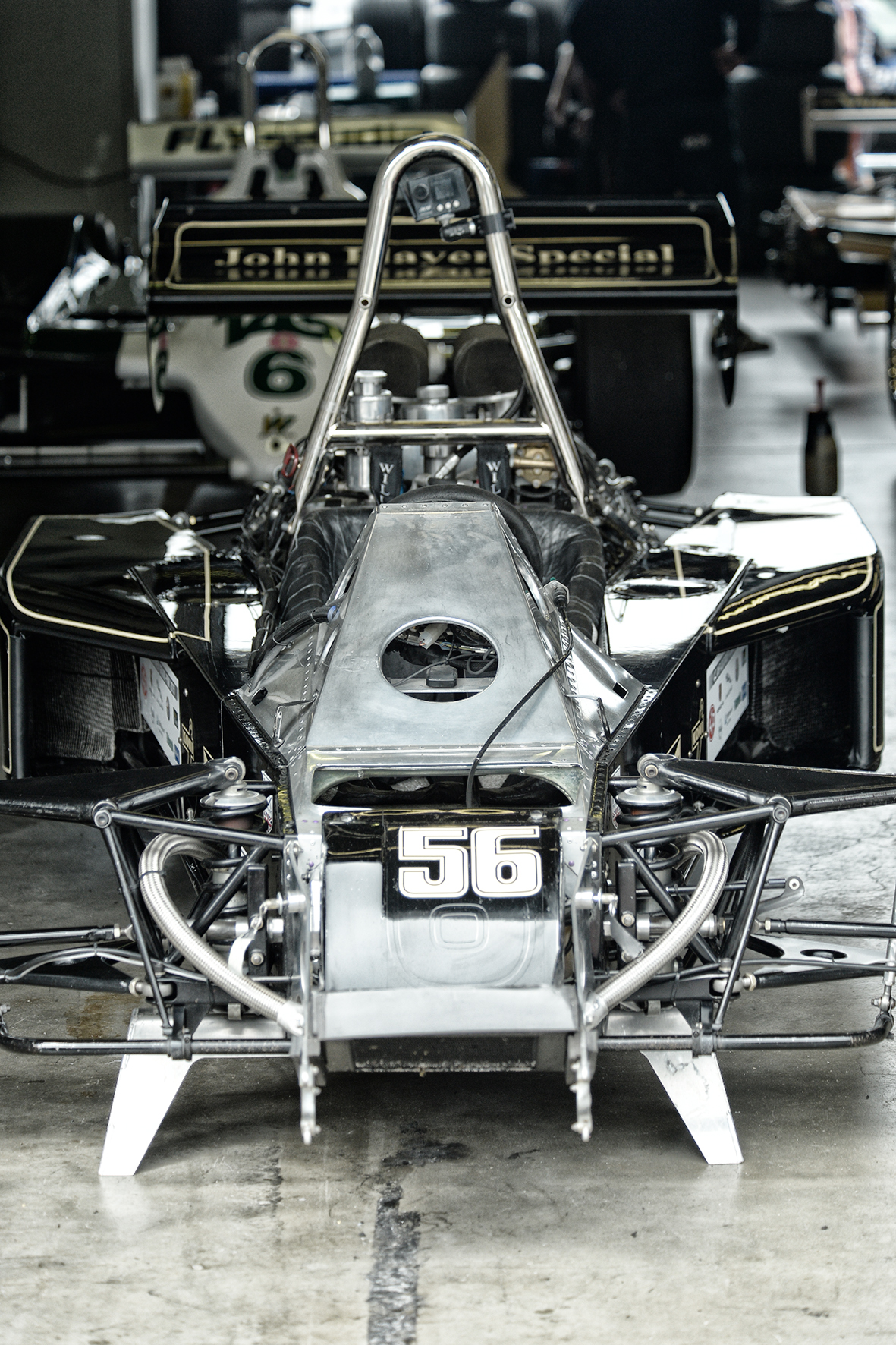

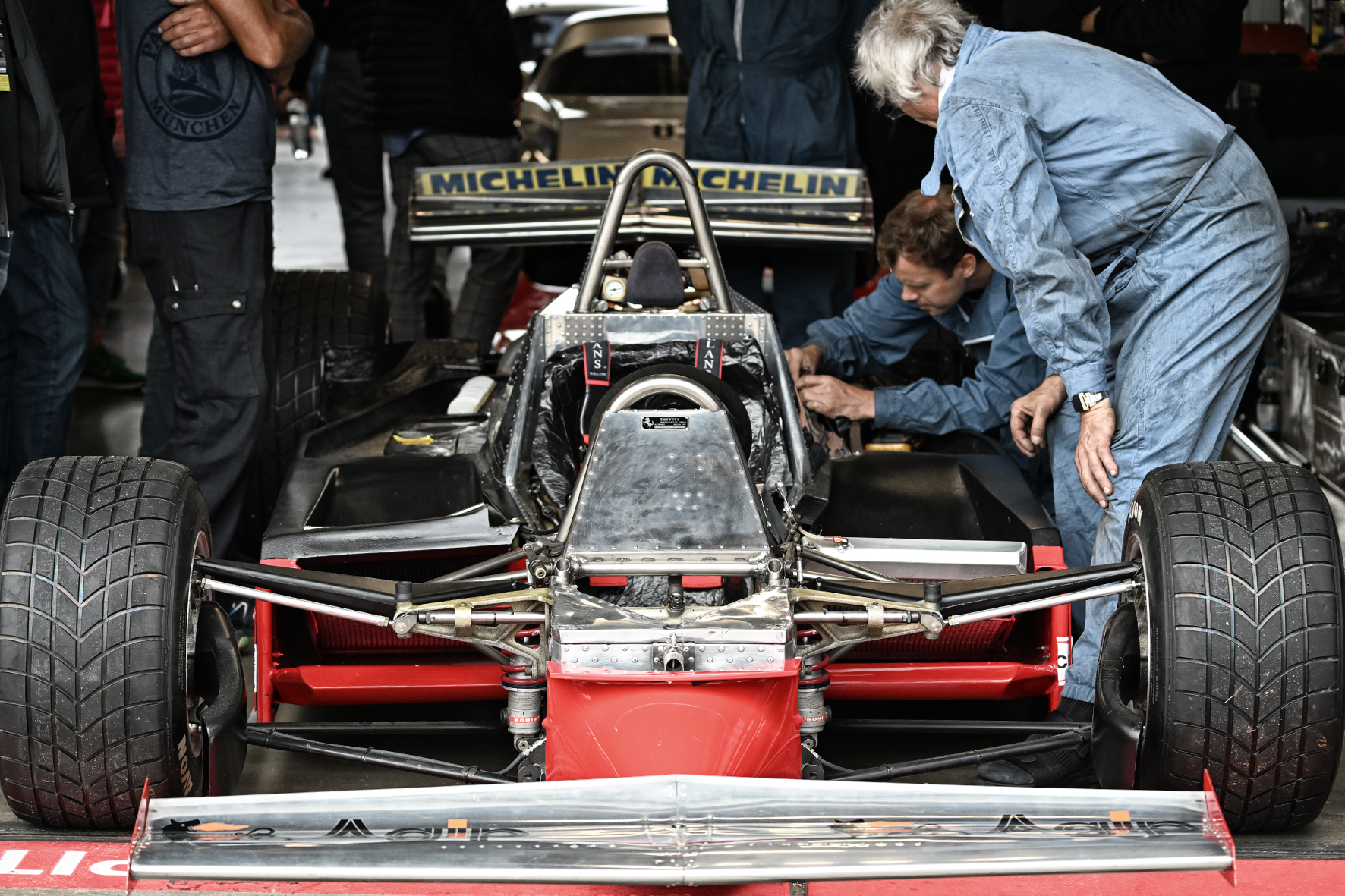

For me, it is always fascinating to gain these insights into the technology and construction of a Formula 1 racing car. Everything is so clearly organised, tidy and well thought out. No unnecessary ballast, everything is designed for functionality and at the same time for weight saving with simultaneous durability and resistance.

Sometimes I am amazed at how simple, constructively logical, some aspects of an F1 racing car are. As a young man I assembled many Tamiya kits of the Formula 1 racing cars of the time. This is perhaps the reason why I recognise and understand some of the racing cars, I’m not really an engineer but just a photographer.

What you can also recognise in the different eras of Formula 1 racing cars is the development in design and construction. The Grand Prix racing cars of the Historic Grand Prix Association, i.e. the Formula 1 cars of the fifties and sixties, are based on a tubular frame chassis, while the later racing cars, starting with the Lotus 49, have a monocoque construction, first made of aluminium in honeycomb construction, then with the appearance of the McLaren MP4/1 made of carbon fibre. The carbon fibre construction is still state of the art today in terms of torsional rigidity, lightness and, above all, safety.

Because if you look at the exposed tubular frame of a Grand Prix racing car today, I at least wonder how you could get in there with a clear conscience, let alone race with such a fragile construction. But to be honest, the aluminium monocoques of the eighties don’t look particularly stable or confidence-inspiring either. But in their day, they were the measure of all things. These racing cars are works of automotive art anyway. In their day, they were the fastest and most elaborate constructions in motorsport and for the respective generation of racing drivers, the goal of their career.

It is also very interesting to see how the designers tried to keep the centre of gravity of their Formula 1 racing cars as low and as central as possible. In some racing cars, this led to the petrol tanks being positioned around the driver – a terrible idea from today’s perspective. It is already recognisable how the safety of the drivers became more and more important without compromising on performance.

The design of the sidepods in the Formula 1 wing car era of the early 1980s is also very interesting to observe. The sidepods were designed as an inverted wing profile, equipped with movable side skirts to channel the airflow under the car. In addition, the side boxes were completely empty except for the radiators. Incidentally, the use of the side skirts is forbidden today at historic motorsport events because it can repeatedly lead to stalling, which then results in a loss of downforce.

All these design details become visible when a Formula 1 racing car is stripped of its panelling – Formula One Car Stripped. Find out more about our photographer Ralph Lüker.