A trip to Wolfsburg, some thoughts about the Bugatti brand, and a reflection on people and their passion for the irrational. Also featuring former East German leader Erich Honecker and a few pigeons who find the whole thing rather odd.

“Look,” Michael, ramp’s editor-in-chief, explained to me on our way to Wolfsburg, “a Bugatti isn’t a car in the conventional sense. It’s a moving work of art – the avant-garde of kinetic art, where movement is an essential part of the piece.” Even when standing still, he said, a Bugatti draws attention to it and remains just as coveted. Driving, he insisted, isn’t the point. In the spirit of Ettore Bugatti, the brand’s founder, each car is a designed artifact. What Bugatti sought was nothing less than poetic engineering – a technological Gesamtkunstwerk with a metaphysical charge.

The roadworks in Wolfsburg were brutal. We circled through the city several times and kept missing the right turn. We were on our way to meet Franco Utzeri, head of the Zeithaus museum at Autostadt – and, in his spare time, a professor of Bugatti studies. He was already waiting for us while Michael continued to elaborate on the philosophy behind the brand.

Anyone who reduces a Bugatti to its performance, I learned, misses the point entirely. Most cars on this planet are built according to rational criteria: speed, comfort, safety, sustainability, design. There are means and methods to achieve such goals. Most vehicles result from a cost-benefit calculation – maximum outcome, minimum investment. A Bugatti, by contrast, is more than just a car. It is a cultural phenomenon that satisfies our curiosity for the superfluous and the irrational. Because nothing about it is rational: neither price nor weight, neither fuel consumption nor practicality. And precisely that is what makes it so desirable.

The notion that people always act rationally is false. There are many forms of desire. Mimetic desire, for instance – we want what others already have. A baby learns to walk and talk because it sees others doing it, and it wants to do it too, only better. Yet within us also lives a diffuse yearning for authenticity – a drive to formulate our own original desires in order to understand ourselves a little better.

People oscillate between dream and reality, inclined to recognize the dreamlike within the real. They long for the irrational. Perhaps the ability to act irrationally is precisely what separates us from machines. To give free rein to one’s moods and emotions – that is the true luxury embodied by a Bugatti. In fact, it’s more than luxury. It is luxury in its purest sense: radical freedom from purpose. A Bugatti doesn’t have to do anything – it just has to exist.

After several phone calls we finally found the right entrance to the Zeithaus. I was eager to see the Bugattis.

On our ramp assignments we’ve driven all sorts of cars: large and small, legendary ones that appeared in Hollywood movies back when I was still playing with a plastic Lada at preschool, brand-new models just off the production line, cars that could rocket like missiles, even vegan cars that run only on hydrogen. But never a Bugatti. To be honest, I had never even seen one. In Berlin, a Bugatti isn’t exactly a common sight.

So where do these artworks graze? I know now: in Germany, mostly in Wolfsburg, in the Zeithaus – the country’s most visited automobile museum. Nowhere else is the history of mobility presented so impressively. On my travels I’ve been to many car museums, including the smallest private one near my summer house in northern Brandenburg. People in the countryside get bored in winter and have plenty of space, so they open little museums on their farms. I like visiting such places.

Once, in a sack museum (yes, really!), I marveled at an exhibit titled Old and New Sacks Through the Ages. My neighbor runs a brick museum in a disused factory, with more exhibits than annual visitors. And near Lake Gudelack there used to be an automobile museum that consisted of just one exhibit: the last government limousine of Erich Honecker, the penultimate head of the East German state council.

He should actually have been chauffeured about in Soviet armored cars – what we in the USSR used to call “body bags”. Our general secretaries were old and barely mobile, and their cars looked like hearses. But Honecker had an irrational love for Citroëns. Over the years he ordered about a dozen of them, each longer than the last. He had the final one stretched to six meters.

After his downfall he wandered aimlessly with his driver, unsure where to go. He wanted to hide at the economics minister’s bungalow in Brandenburg – but the angry populace was already there, having “liberated” the house and now eyeing the fallen tyrant’s car. Had Honecker owned a Bugatti – or at least a Ferrari – he might have stood a chance of escape. But his Citroën wasn’t built for speed, and besides, the people were everywhere. Like in the fable of the hare and the hedgehog, the hare stood no chance – wherever he ran, the clever people were already there.

His young driver, a local from Brandenburg, knew a pastor near Lake Gudelack and took his boss to the church, where he could hide for a short time. As a token of gratitude, Honecker supposedly gave the pastor his car. So the legend goes.

The Citroën stood in the churchyard for years; anyone could come look at it, and if the owner was in a good mood, you could even sit inside. Eventually it was sold to a collector. That was the smallest car museum I’ve ever visited. The Zeithaus, by contrast, is huge – and because its halls are full of mirrors, you get the feeling of being surrounded by vintage cars wherever you look. In Wolfsburg, I thought, there are more cars than people.

A city built around a factory – an industrial city in a post-industrial age – Wolfsburg lives and breathes Volkswagen. When the company thrives, the city shines: tourists flood the pedestrian zones, shops and ice cream parlors fill up, young musicians play in the streets, hotel bars buzz with predominantly male guests animatedly gesturing over their drinks. From a distance, they look like football fans, but in truth they’re new-car buyers waiting to pick up their vehicles at the factory and tour the world of automobiles.

But when Volkswagen catches a cold, the whole city coughs. Streets empty, construction sites go silent, the vacant shops lose their charm. Open are: opticians, hearing-aid stores, pharmacies, savings banks. On the day we visited, there were barely any people on the streets. Only pigeons sat on the empty café chairs, watching us as if to say: “What are you doing here? Need new glasses? A hearing aid?” The pigeons knew nothing about cars. And we? We just wanted to see a Bugatti.

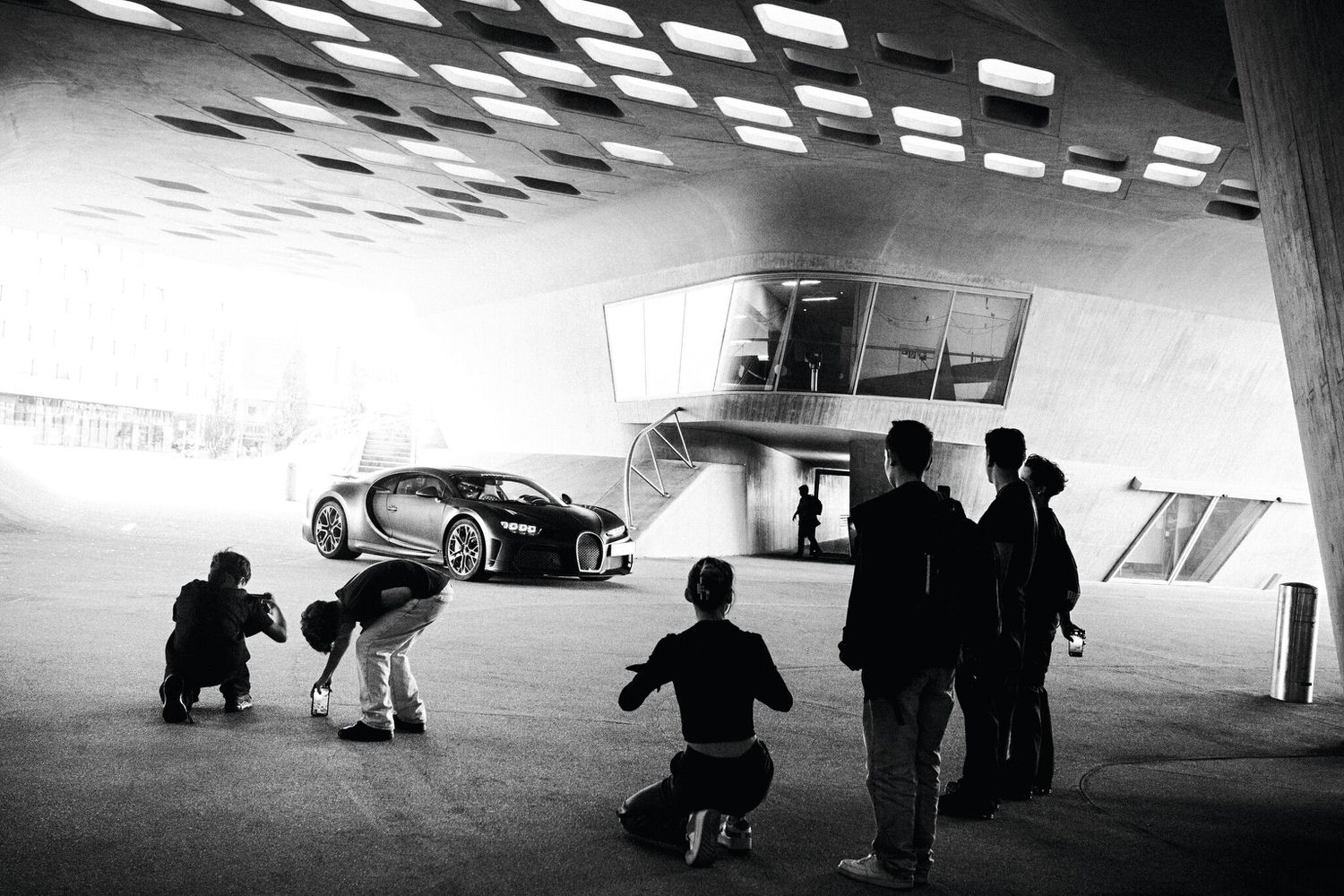

Only in front of the Zeithaus was there life: a school class from Holland (surely skipping school for good reason), endlessly vaping young men, and families with toddlers, all standing in a semicircle around two Bugattis parked (for Michael and me) in front of the museum. Which awards these cars hadn’t won is hard to say – world’s most expensive, fastest street-legal cars, victors of Monaco and Le Mans alike.

They were stars, adored by everyone. Every kid and every grandma wanted a selfie with the cars. One of them had once hit 491 km/h, the other 460. On the roof of one sat a city pigeon, utterly shameless and clearly plotting something. Did this bird, capable of 80 km/h on its best day with a tailwind, have any idea what kind of rocket it was perched on?

Franco greeted us at the entrance. He had a lot to tell. “Autostadt,” he said, “is a unique place where mobility becomes an experience. It’s not just about displaying cars, but about culture, history and the future. Families, tech enthusiasts, design lovers – they all find their way into the world of the automobile here. The architecture, the pavilions, the exhibitions – it’s a total experience. We want to spark emotion and convey knowledge. For me, Autostadt is far more than Volkswagen’s showcase – it’s a cultural space that builds bridges between past, present and future.”

Of course, he also talked about Bugatti. The brand’s story is both glorious and tragic – about people who, obsessed with an idea, pursued their dream through the twists of history, winning and losing along the way. Ettore Bugatti, an automobile designer from Milan, was possessed by the vision of creating the fastest and most beautiful car of all time – one that would unite supreme luxury with sportiness. In 1909 he moved to Molsheim in Alsace, where he found everything he needed to bring that dream to life. At the time Molsheim was part of Germany; after the First World War it became French, and ever since Bugatti has been considered a French brand. Its mantra: art, form, technique.

The distinctive teardrop silhouette, the iconic horseshoe grille, the flowing lines of light – all form a language that defies trends. Then there’s the engineering. For Bugatti, technology isn’t mere functionality in service of a goal; it’s transcendent precision. Every detail is oversized, excessive – and that’s precisely why it’s so extraordinary.

A Bugatti achieves more than anyone could ever need. Its technical specifications defy reason, and in that excess, technology becomes a sensual experience – not because it’s useful, but because it inspires awe. Technology as a stage for grandeur. More than a machine – a cultural achievement.

Ettore had intended to pass the company to his son, but the young man swerved to avoid a drunken postman on a bicycle, crashed one of the latest models into a tree, and died. After World War II, a second son took over, but public tastes had changed – elegance and extravagance were no longer in vogue. The brand passed through several hands, yet the idea of a supersonic luxury car endured.

So when you compare a Bugatti with other race cars, it stands apart. There’s simply nothing like it. They’re essentially built for museums – which perhaps explains why you don’t see many on the road. I asked Franco how many Bugattis are currently driving around the world, and whether he knows all their owners personally. There are only a few hundred, he said.

“So the chances of two Bugattis meeting are practically zero,” I concluded.

“I wouldn’t say that,” replied Franco. “Depends on the intersection.” Many of them, he noted, end up in Monaco. You can easily imagine several cruising the city there – though driving a Bugatti in Monaco is torture: one tap on the gas and you’re already in France.

Bugatti Veyron Super Sport World Record Edition

- Engine quad-turbocharged W16

- Displacement 7,993 cc

- Power 1,200 hp (882 kW) at 6,400 rpm

- Torque 1,500 Nm at 3,000 rpm

- Weight 1,838 kg

- 0–100 km/h 2.7 s

- Top speed 431 km/h (Guinness World Record 2010)

Bugatti Chiron Super Sport (Prototype)

- Engine quad-turbocharged W16

- Displacement 7,993 cc

- Power 1,600 hp (1,177 kW) at 7,050–7,100 rpm

- Torque 1,600 Nm at 2,250–7,000 rpm

- Weight 1,995 kg

- 0–100 km/h 2.4 s

- Top speed 440 km/h (electronically limited)

Text Wladimir Kaminer | Photos Matthias Mederer · ramp.pictures

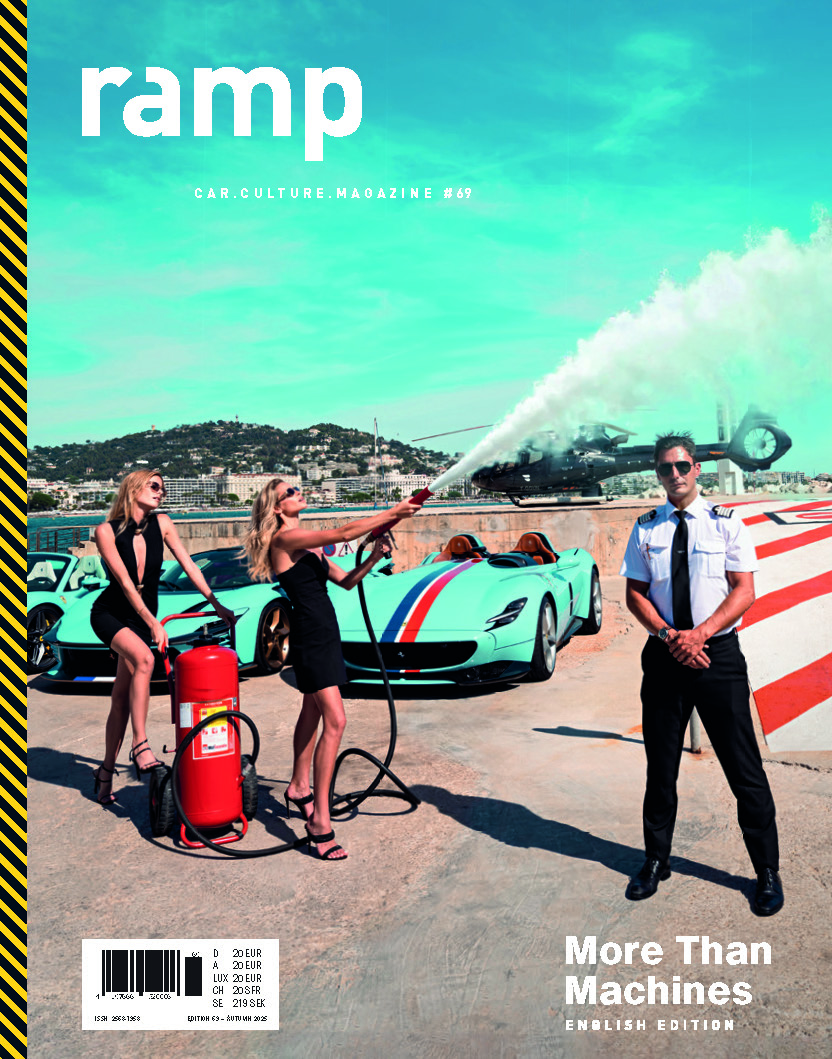

ramp #69 More Than Machines

Maybe it all starts with a misunderstanding. The mistaken belief that humans are rational beings. That we make decisions with cool heads and functional thinking, weighing and optimizing as we go. And yes, maybe sometimes we do. But only sometimes. Because in truth, we are not reason, we are resonance.

And so this issue of ramp is a cheerful plea. For beauty that needs no justification. Find out more