In 1963, a young guy from Ohio named Roger Penske was nearing the end of his career as a race car driver. His time behind the wheel of fast cars had earned him accolades, with numerous road racing wins, Sports Car Club of America Driver of the Year honors in 1961, and one NASCAR win at the wheel of a late-model stock car. He would continue competing until 1965, but on that day in 1963 when Penske recorded his sole NASCAR win at the wheel of a Pontiac Catalina at Riverside International Raceway near Los Angeles, it wouldn’t have taken a seer to predict that this smart and ambitious young man’s future wouldn’t be focused on driving race cars.

Like Penske, Pontiac was nearing the end of major on-track motorsports participation when the young hot shoe took the wheel of that big late-model stock car. Pontiac, too, had seen success on the track. In fact, for a couple of years preceding the Riverside race, Pontiac had dominated NASCAR competition and had developed a devoted following of race fans.

I was an impressionable 13-year-old one summer night in 1961 when the twenty-something uncle of a friend took me and a group of local kids out for ice cream in his ’61 Catalina convertible. Ice cream was a rare treat for me in those lean times in my working-class Chicago neighborhood, but riding in that Catalina with its 389-cublic-inch V-8 and four-speed transmission was much more than a treat. It was a chance to hear and touch the car of my youthful dreams. It was the closest this car-crazy kid could hope to come to the Ponchos that were dominating NASCAR competition.

The ’61 NASCAR season included a whopping 52 events, with highlights broadcast nationwide at least once on ABC’s Wide World of Sports. At the Daytona 500, NASCAR’s premier event, Pontiac finished first, second, and third, a commanding performance that earned the brand both fans and showroom traffic.

Like Chevrolet, Pontiac was a latecomer to modern engine technology when it introduced its first V-8 in 1955. So, like Chevrolet, its design was a bit more advanced than some of the other Detroit V-8s, and it had a leg up on Chevrolet early on with more displacement. And when Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen took over the reins of the moribund Pontiac division in 1956, performance and auto racing became part of the brand revival plan.

The first Pontiac to make noise in NASCAR was the Chieftain of driver Cotton Owens and Pontiac racing guru Ray Nichels. The potent Poncho topped 100 mph and won the Daytona race on the old beach course in ’57. The following year, master mechanic Smokey Yunick fielded a Paul Goldsmith-driven Pontiac and gave the brand back-to-back wins in the last two races on that hallowed strip of sand.

Nichels, Yunick and Pontiac were far from finished, and they returned to win the 100-mile qualifying race in ’59 on the new Daytona International Speedway, with local resident Fireball Roberts at the wheel. That was the beginning of Pontiac dominance in NASCAR racing. In ’61 the brand won 30 of the 52 races and came back the next year to win 22 of 53 while capturing the Manufacturer’s championship. Winning teams included Fireball Roberts with Smokey turning wrenches, Joe Weatherly and Bud Moore, Paul Goldsmith and Ray Nichels, and David Pearson with Ray Fox handling the mechanical side of things.

Winning was the order of the day, and at the beginning of the ’62 season with the newly-released Super Duty 421 version of the brand’s venerable engine under the hood, Pontiac won seven of the first eight NASCAR races. No wonder youngsters like me thought Ponchos were invincible.

By ’62, despite cylinder head refinements, a Super Duty parts program, a displacement increase, and tuning tweaks, Pontiac’s engine technology was getting long in the tooth. Ford’s 427 and Chrysler’s 413 wedge showed more potential, and waiting in the wings were the big-block Chevy, the Chrysler 426 Hemi and the not-for-NASCAR but scary-powerful Ford SOHC 427. GM management is said to have prohibited Pontiac from completing development of more advanced race motors, although some new prototypes were in the GM engine labs.

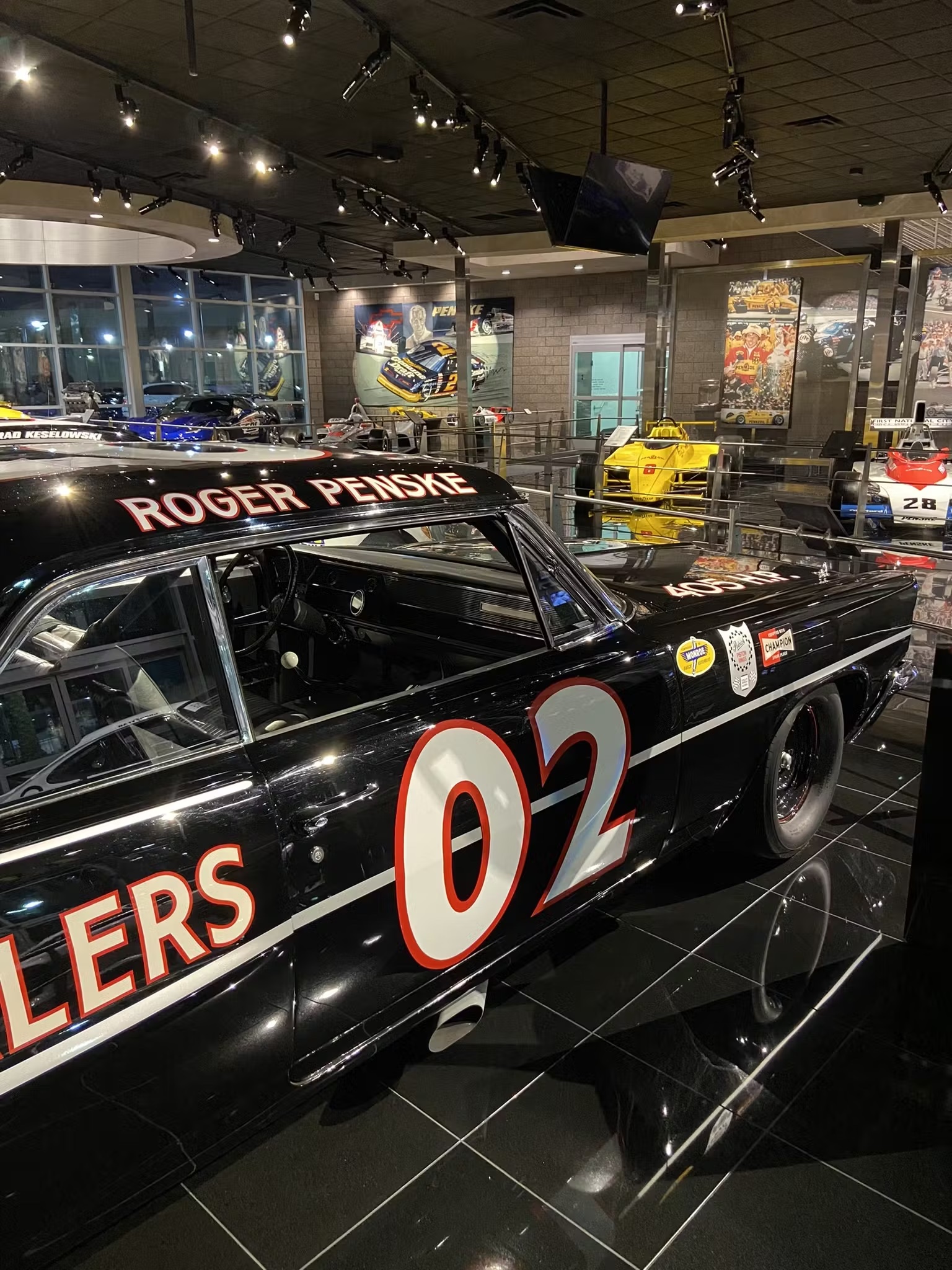

Probably in a nod to federal regulators who were trying to enforce factory racing bans, GM pulled the plug on Pontiac’s ’63 NASCAR campaign just weeks before the Daytona 500. GM chose to focus its unofficial racing efforts on the Chevrolet brand, in part perhaps because Knudsen had been promoted to the top job at Chevrolet. To the dismay of fans like me, Pontiac race cars were put out to pasture. But the groundwork had been laid, and a fast and fully developed ’63 Catalina late model stock car was available to privateers.

While Pontiac was dominating in the early ‘60s, Penske was a consistent winner in sports car racing. Like many racers of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, Penske got his start in hill climbing, a form of autosport that dates back to the 19th century. In its standard format, racers climb a hill at full throttle (or as much throttle as traction and control will allow.) The cars take on the hill one at a time, and each attempt is timed. The winner is the racer with the quickest time. It’s a reasonably safe and straightforward form of motorsport for both driver and car.

But it wasn’t enough for the young Penske, and he soon graduated to road racing, competing in SCCA events at Vineland Raceway in New Jersey. Porsche was his weapon of choice, and he succeeded admirably, winning the 1961 D Modified national championship and earning SCCA Driver of the Year honors. In ’63, he drove a Ferrari 250 GTO to second place in a Daytona sports car race, and was a regular top dog in national competition. So, it was unusual but probably no surprise that Ray Nichels, who owned a Chicago Pontiac dealership and had managed Pontiac’s racing efforts for Bunkie Knudsen, asked Penske to join the ranks of racers who had driven for Pontiac in NASCAR stock car racing events.

Dan Gurney is said to have urged Penske to try his hand at stock car racing, explaining that piloting the big cars on a race track was no more difficult than sports car competition, and, in his opinion, the NASCAR stock cars of the day were safer than most sports cars. He added that he found it amazing how well they handled.

In a first effort in the Yankee 300 stock car race at Indianapolis, Penske, the ’63 Catalina, and the Nichels race team retired with a failed differential after leading 53 laps. A.J. Foyt went on to win that race. Their performance apparently impressed Riverside’s Les Richter enough to invite them to compete at his 250-mile NASCAR-sanctioned race at Riverside in California, a track that was very familiar to Penske, who had won the Los Angeles Times Grand Prix at that venue in ’62.

The 250-mile Riverside event didn’t begin well for Penske. He had only been able to practice briefly as he had a day job to tend to. Nevertheless, he qualified 12th, but contact with the spinning Mercury of Darrel Dieringer on lap one left him dead last. In an interview with the Times following the race, he said, “I just waited on that hill ‘til everyone had gone by before I tried to get back into the race.”

And back into the race he went, fighting his way to the front of the pack. From there it was a battle between Penske and Dieringer, who had also recovered from the lap-one contact. At the checker, Penske the sports car racer crossed the line a second ahead of the Mercury driver, with the rest of the pack, which included NASCAR champ Weatherly and a guy named Ken Miles, among other notables, more than 30 seconds behind.

That successful foray in stock car racing would prove to be Penske’s first and last as a driver. He would continue jockeying sports cars for a couple of years in national events, but his focus became more and more fixed on building a future.

And build a future he did. In 1965, Penske climbed out of his racing seat and began to forge an automotive empire. Today, he’s chairman of Penske Corporation, a stakeholder in Penske Automotive Group, which operates auto dealerships worldwide. The Corporation is also responsible for Penske truck Leasing and Penske Motor Group, owner of dealerships in California and Texas. In 2019, Penske purchased Indianapolis Motor Speedway, home of the Indy 500 and a veritable temple of automotive racing history. That came as no surprise, since Penske Racing is synonymous with that racetrack, having won the Indy 500 19 times. He also owns the IndyCar series.

Penske’s teams are also regular competitors in a variety of international auto racing formats, usually with great results. His race teams have seen tremendous success in NASCAR, most memorably perhaps with a one, two finish in the 2008 Daytona 500, the 50th running of that classic race. NASCAR series championships and hundreds of race wins have followed. Known to his race teams as “The Captain,” he takes an active role in strategizing on-track action. In brief, Roger Penske has achieved phenomenal success since he left the race car cockpit nearly 60 years ago.

Pontiac, on the other hand, had a rough go of it. The brand built on its winning NASCAR stint with successful product development, including the GTO and Firebird muscle cars. But with an ever-more foggy brand identity and no racing program providing motivation and PR, there was little brand-centric performance engineering coming from the Pontiac division. In fact, the last of its muscle cars were powered by what were essentially Chevrolet engines. In 2009, GM, an automaker with too many brands in a severe economic climate, pulled the plug on its once dominant performance division. A sad end for the brand a certain 13-year-old loved some 63 summers ago.

Report by Paul Stenquist for hagerty.com