Victoria Bruno leans over the yellow fender of the Daytona on the blue two-post lift to point at the throttle linkage. “Every single one of those pieces was plated differently.” She points at cotter pins, circlips, rods, nuts. “If you look under the hood of a different Ferrari and they’re all the same color, that’s incorrect.”

Two and a half years ago, the newest employee of Patrick Ottis Company in Berkeley, California, had never held a wrench or ratchet. This morning, she was painting the aluminum castings of a flywheel case for a Ferrari V-12 that had suffered a water pump failure, years of storage, then a hurricane. It’s her first engine rebuild at the shop.

If you don’t know who Patrick Ottis is, you probably don’t own a Ferrari. Trained in automotive restoration by Stirling Moss’ racing mechanic, Alf Francis, in Oklahoma City, Ottis moved to the San Francisco Bay Area to work with Stephen Griswold, the famous Bay Area Ferrari dealer and a pioneer in restoring cars. When Griswold moved to Italy, most of his employees stayed, all packed together in this little section of Berkeley, and started their own restoration shops. Ottis was one of them. Founded in 1982, his shop boasts multiple wins at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, and Ottis has judged there for nearly 30 years.

“A question I get a lot is, ‘How did you get your job?’” says Bruno, at lunch, over chicken tacos at a taqueria around the corner from the shop. Her red crewneck is dusted with baking soda and smudged with grease, her brown hair cut to a chic but practical length just below her jaw. “I picked up the phone and I called.”

The youngest child of a commercial property manager and an accountant, Bruno didn’t grow up in a family that treasured cars, though her grandfather daily-drove a ’66 Mustang. Whenever it needed mechanical work, he diligently took it to the shop. When Bruno expressed interest in working on it, she received gentle discouragement—you’ll get your hands dirty, she was told. Without access to the world of automotive restoration, and without encouragement from the few Los Angeles–area shops she walked into, she decided to chase her dream on her own: She’d save money, buy a car, and teach herself how to restore it.

The Covid pandemic spurred her to chase harder. Laid off from her restaurant job, Bruno realized she was miserable. “I just asked myself one question: Whether you’re paid or not, and whether you have the skill set or not, what genuinely do you want to be doing all day, every day?” She went back to Google—and this time, changed her search from “automotive school” to “restoration school.” That’s how she found McPherson College, home of the world’s only four-year degree in automotive restoration. In the tiny town of McPherson, Kansas, she found teachers who not only understood her passion but could teach her what she so desperately wanted to know. After enrolling in community college in California and completing the required credits to transfer into McPherson as a junior, she drove to Kansas in her EcoDiesel Wrangler and threw herself into the world of vintage cars.

“I didn’t know anything, and all I did was, well, commit my whole life to it and all my time and all my energy.” She leaped at the opportunity to work with a team of students on the school’s Pebble Beach entry, a Mercedes-Benz 300S. “It needed to be restored to a caliber that none of us had ever attained before,” she says. The year that Pebble accepted the Mercedes for the Concours, Bruno applied for a scholarship to accompany the car to the golf greens. When she learned that she got it and would be back in California, she decided to call Ottis and ask to see his shop. “I didn’t really think this one through too much,” she says; at the time, she was interning with a huge competitor of the shop, Motion Products Inc. in Wisconsin. It didn’t matter, as things turned out: “Immediately—this is something he does to anybody and everybody who walks by and says, ‘Whoa, what do you have in there’—he’s like, ‘Come on in, let me show you around.’”

Ottis invited her to stay as long as she wanted and ask as many questions as she wanted. A month later, Bruno showed up at 1220 10th Street, and Ottis and his son Tazio took her to lunch. “We get back from lunch and he says, ‘Hey, do you want to assemble those cylinder heads on the 225 Sport?’” Bruno was shocked; he hadn’t even seen her résumé. He didn’t need to: She grabbed a spring compressor, the red line, stood on a stool, and put them together. “What are you doing after graduation?” Ottis asked.

All five full-time employees of Patrick Ottis Company focus on mechanical work; their projects are split evenly, Bruno says, between full restorations and service jobs. You won’t find a paint booth in this tidy, airy shop, whose high ceiling is punctuated with skylights and hung with 12 mercury lights, but you will find Sun machines for setting advance on distributors; a soda machine for blasting parts; lathes; drill presses; and drawers and drawers of Ferrari-exclusive tools—some improvised, some not.

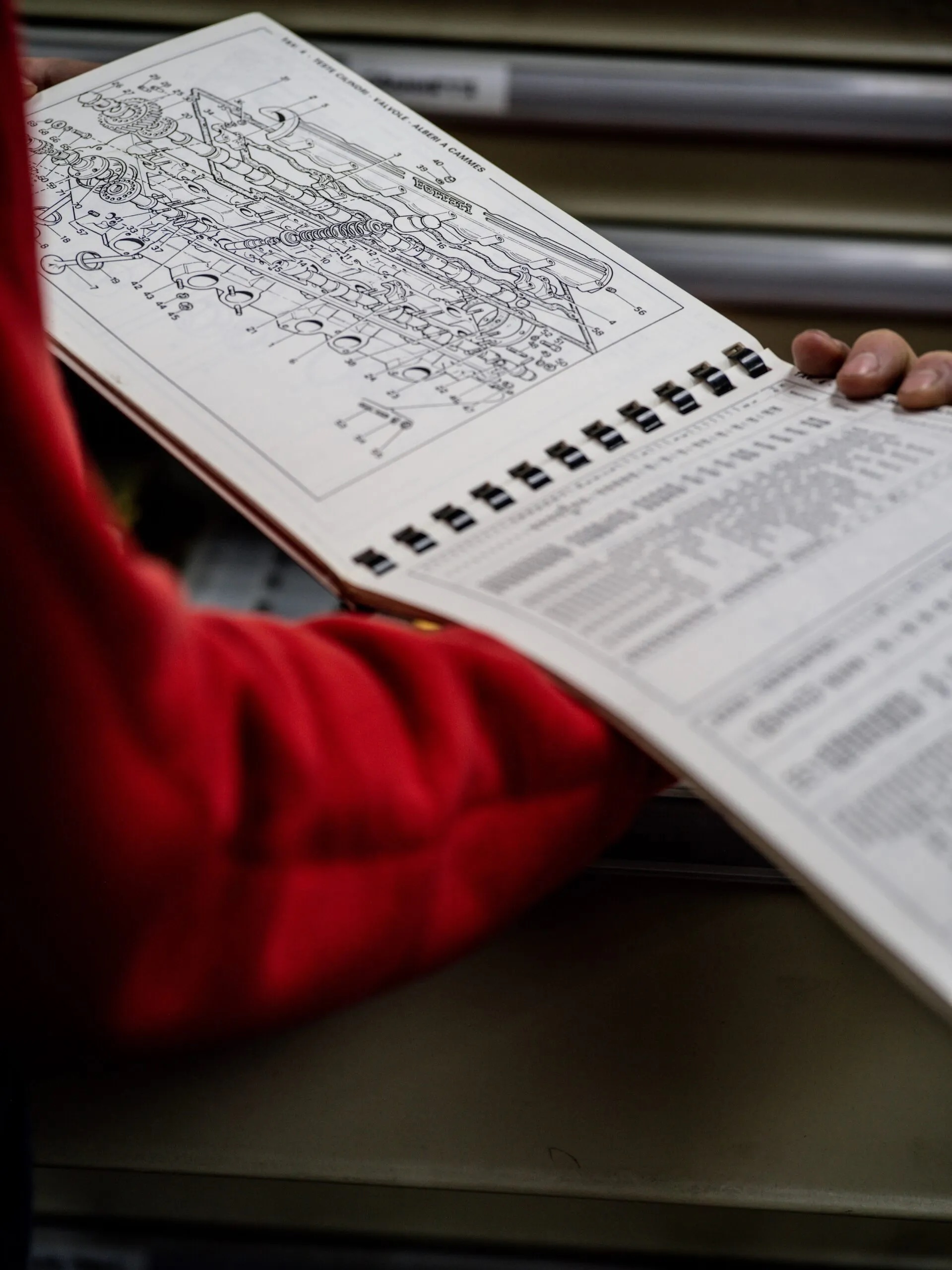

“Let me show you the ring nut drawer,” says Bruno, her manner somewhere between proud parent and joyful museum guide. “We have a complete set.” She walks to a wall of tool chests and opens a shin-height drawer, its label neatly Sharpied in black, to reveal a mass of toothed metal ring with a flange on one end. Transmissions, engines, gearboxes—Ferrari standardized no parts, instead choosing whatever dimension or measurement fit the parameters of a particular car. None of the ring nuts are labeled because none of the gears are labeled, but whatever a Ferrari mechanic might need is in this drawer. Bruno used one just the other day to assemble the valvetrain on the engine rebuild she’s doing. She jogs to the other room, where her desk is, and grabs the manual—which, like any correct radiator cap on a Ferrari, is all in Italian. “Google Translate comes in handy,” she laughs.

As soon as she came on as a full-time employee after graduating in 2023, Bruno began to document her work at the shop on her Instagram, using the handle @motoribruno, or Bruno Motors in Italian—after clearing it with Ottis, of course. “He was like, ‘You should absolutely be showing, telling people what you do, because we need more people.’” When her content began to gain traction—she now has 133,000 followers as of this writing—she had to check in with him again. She received the same support. Bruno uses the account to document not only her daily and weekly projects in the shop but also her activity in the automotive world—she has recently appeared on a Cars & Culture podcast on SiriusXM and judged at the Ferrari-only Cavallino Classic in Palm Beach, Florida. She’s even working with a local handmade goods shop to sell Motori Bruno–branded goods, like the black tote sitting beside her desk. You could read the bag and her vintage Lee jeans (they were her mother’s) and Red Wing boots as an influencer’s blue-collar accoutrement, but Bruno is simply, utterly thrilled to be doing what she’s doing. When she first started working at the shop, the older hands had to warn her of burnout: working seven, eight, nine days in a row was unsustainable.

“It’s my passion, it’s truly what I love. So if I can let other people know that if they can also follow their passion—whether that [passion] is conventional or unconventional—then they should.”

She doesn’t see her activity on social media as influencing, per se, or building her brand: “I was just trying to share my passion with other people and expose younger people to the industry.”

The generational change is evident in the Berkeley shop—but thanks to the presence of Bruno and Tazio, Ottis’ son, the talk about the shop’s future is anything but morbid.

Tazio stands next to his father beside a silver SWB. Upon his son’s request, Ottis has just walked in from the front desk to identify the year of the car, which he states as late ’61, early ’62. How does he know? Ottis points to a curved vent on the rear fender. “That’s how I know.” He speaks softly but lays dramatic emphasis on the pronoun, glancing at his son with a hint of a smirk. Tazio, named after Nuvolari, grins easily.

Now managing all the bigger projects, like the nut-and-bolt restoration of a Daytona, Tazio says he started on the books in 2015. He is interrupted by Ottis: “Let me just say one thing, then I’m gonna go to work—he was taking carburetors apart when he was 5, he was making parts on the lathe when he was 9. I didn’t force-feed any of that… he was born into it.”

The heir of the shop brings different flavors of the same automotive passion into the picture: Not only does he own an amateur race team and race in IMSA, but he and two other business partners have recently opened a classic car brokerage. In addition to being an excellent mechanic, he has a sense of the market and of the customer base. The shop is already seeing a generational shift in its customers, which he views as part of a natural transition of collectors’ attention toward newer cars: “Special 288 Competition cars and F40 LMs and stuff like that are going to be the car that my generation falls in love with—watching them race at Le Mans, similar to these Alfas, you know.” He gestures at a prewar Tipo 6C Gran Sport 1750 toward the back of the room. “They’re incredibly special—amazing, amazing cars, but the generation that really knows about them and loves them is becoming fewer and fewer.” His favorite customers are those who “just get it,” like one who owns multiple halo-spec race cars and “thrashes the s*** outta them.” Tazio declares him “a real enthusiast.” When Bruno started working at the shop, Tazio “was stoked—she brings good energy and passion to the shop, which is good for it. It’s nice to have people who are really stoked in the older cars.” Bruno, in fact, works exclusively on the carbureted cars.

It’s a mellow, relaxed afternoon in the shop. After fiddling with the carburetors on a SWB and doing some paperwork, Ottis leaves. Tazio sits courteously for a few photographs, then departs. Bruno remains, the sole guardian of the shop and its millions’ worth of metal. We’re waiting for the light to soften for a final photo. The shop is quiet. Bruno turns to me with curious excitement. “Have you been in a Ferrari?”

Report by Grace Houghton for hagerty.com